About a month ago, I bumped into an old friend by sheer chance on the streets of Nairobi. Night Atieno and I grew up together in the same city estate and, although we hardly met thereafter, every encounter was an opportunity to catch up and laugh about the good old estate days.

After the usual exchange of pleasantries, Night straightaway asked me what my thoughts on the impending August general election were. “We are planning to vote very early in the morning, after which we must leave town by latest 9am,” she said. “We will then drive all the way to Mwanza. By nightfall, Inshallah, we shall be taking supper with my in-laws.” Mwanza, the second largest city, after Dar es Salaam, is the lakeshore town in the northwestern region of Tanzania.

THIS TIME, THERE’S NO GOING TO THE SUPREME COURT

Looking at me right in the eyes, she whispered: “Listen, this time, there’s no going to the Supreme Court.” She was referring to the first ever Presidential Election Petition case No. 5 taken to the inaugural Supreme Court of Kenya in March 2013 by the Coalition for Reform and Democracy (CORD), the opposition coalition led by Raila Amolo Odinga, seeking to overturn the election victory of the Jubilee coalition led by Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, today the fourth president of Kenya.

On March 9, five days after the general election that was held on March 4, 2013, Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC), through its then chairman Issack Hassan, announced the election results thus: Uhuru Kenyatta — 6,173,433 votes which constituted 50.07 percent of the total votes cast, beating Raila’s 5,340,546, which comprised 43.31 percent.

Suing the IEBC on March 16, 2013, Raila sought to stop the swearing in of Uhuru as a president. It never came to pass. Uhuru was sworn in as the president on April 9, 2013 at Kasarani Stadium.

The Supreme Court judges led by then Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, in arriving at their verdict, said: “In summary, the evidence in our opinion, does not disclose any profound irregularity in the management of the electoral process, nor does it gravely impeach the mode of participation in the electoral process by any of the candidates who offered himself or herself before the voting public.”

The judges further said: “It is not evident, on the facts of this case, that the candidate declared as the president-elect had not obtained the basic vote-threshold justifying his being declared as such. We will therefore disallow the petition, and uphold the presidential election results as declared by IEBC on March 9, 2013.”

That Supreme Court judgment read under less than 10 minutes cast a shadow of devastation and disquiet over the opposition’s core supporters. The promulgation of the new Constitution in August 27, 2010, had created the hitherto new Supreme Court and heralded a new confidence in a much-maligned justice system among Kenyans in all walks of life.

So, when Raila went to the Supreme Court to seek electoral justice, his loyal supporters who had just fervently voted for him, believed in the benign promise of a new court that had promised to dispense justice without fear or favour. It is not hyperbole to state that ever since the reading of that very short judgment by former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, a majority of Raila’s supporters have yet to overcome the spirit of deflation that engulfed them.

When Raila went to the Supreme Court to seek electoral justice, his loyal supporters who had just voted for him, believed in the benign promise of a new court that had promised to dispense justice without fear or favour

To date, the subject of one of the shortest judgements ever passed by a Supreme Court, has become a taboo narrative among opposition supporters and even among some of the leading lawyers across the country. “Let’s just put it this way,” a prominent Nairobi lawyer who did not want his name disclosed, told me, “The Supreme Court failed in its maiden moment to inspire confidence among Kenyans. It made this worse by its mode of presentation of the verdict.” The lawyer said even among themselves as senior counsels, the conversation around the Supreme Court judgement leaves “a sour taste in the mouth.”

In a parting shot, Night, who is a businesswoman, told me “Kama mbaya, mbaya…wacha wanaume waonane.” If the worst comes to the worst…so be it. Let men face each other!

Night’s scheduled temporary migration in August is part of a silent movement that has been taking place since December among the people of Nyanza and the larger western Kenya who live in Nairobi city, Eldoret and Naivasha towns.

“In the guise of travelling upcountry for Christmas holiday 2016, many family men from the ghettos of Nairobi transported their wives and children to their rural homesteads in Nyanza and Western Kenya,” said my source who spoke to me in confidence. “The month of December was just the right time because the children were on holiday, were relocating to their rural homes and so there was ample time to transit to new schools.”

“I’m a board member of a school in Siaya County,” my confidant told me. “When we sat in January 2017, to admit fresh pupils and pupils seeking transfers, we dwelt mainly with parents from Nairobi and Eldoret.” Investigating further on where the parents from Nairobi were from, he found out they largely came from Kariobangi North, Mathare North, Mathare 4A, Ngei/Huruma and Ngomongo.

It is not for nothing that the parents from some of the toughest slums of Nairobi are sending their children and extended family back home. These slums, today divided between Embakasi North, Mathare and Ruaraka constituencies, were the sites of bloodletting following the bungled December, 2007 general election that led to at least 1,400 people getting killed and 600,000 Kenyans displaced countrywide, especially in the Rift Valley region.

These ghettos, which are inhabited largely by the two “antagonist” ethnic communities — the Kikuyus and Luos — exploded into violence on December 30, 2007, when young men from the two communities faced off with weapons such as daggers, hunting knives and, pangas.

NOBODY IS TAKING ANY CHANCES, ESPECIALLY IN THE NAIROBI SLUMS

Regardless of whatever outcome is anticipated a month from now, given the heightened tensions, “Nobody is taking any chances, least of all the people living in the slums, who bore the greatest brunt of the violence,” said my informant.

If the slums are witnessing a vertical exodus, that of families moving from the urban to the rural, the men who have remained behind have been also moving, but horizontally. In Ngei and Huruma slums, which are in Mathare constituency, and are adjacent to each other, Luo and Luhya men have been changing houses, moving closer to their kinsmen within the same area. In the sprawling Mathare slum. for example, there are areas that are predominantly populated by Kikuyus, while others are populated by Luos. This “cross-border” movement — of shifting rented accommodation to beef up and secure their respective ethnic group safety— has been going on since January.

If the slums are witnessing a vertical exodus, that of families moving from the urban to the rural, the men who have remained behind have been also moving, but horizontally

In the peri-urban areas bordering the city on the south, a similar movement has been also taking place. Non-Kikuyus, mostly Luos living in the Riruta Satellite area, too have been sending their family back to their ancestral homes in western Kenya. Riruta Satellite is a quasi-rural, quasi-ghetto,village bordering the Waithaka area, mainly populated by Kikuyus.

Riruta and Waithaka areas are in Dagoretti South constituency, which in Kenyan political parlance “belongs” to the Jubilee Party coalition. A friend — a veteran journalist who worked for the defunct Kenya Times in the 1980s and is from the Luo community and who has lived in Riruta Satellite for close to three decades — confided to me that his kinsmen have been shipping their families back home during the December and Easter holidays.

To the north of Riruta is Kawangware, a sprawling ghetto today populated equally by Kikuyus and Luhyas. Many Luhya families were settled in Kawangware and Kangemi areas, which are in Dagoretti North and Westlands constituencies respectively, during the time of Fred Gumo when he was appointed as a City Council commissioner by former president Daniel Arap Moi in 1989. Gumo was later to serve as a three-term MP for Westlands.

GET THE AWAY FROM SODOM

The Luhya families, like their counterparts from the Nyanza region, have relocated their wives and children — “Wacha wao waende nyumbani tubaki tukilinda mji (Let the women and children be sent away so that we men can remain to guard the homes),” a Luhya man from Sodom told me. Sodom is a sprawling slum in Kangemi that stretches down to the valley that borders the leafy suburb of Lavington.

During the 2007-2008 post-election violence, Sodom, especially the area around Kihumbu-ini Primary School and Kangemi gichagi (village), became a site of violence pitting the Luhya community against the Kikuyu, who consider themselves indigenous to the area.

The slumlords who had built the timber shacks rented by the Luhyas quickly changed sides and, as the violence spiralled into us vs them, meaning the Kikuyus versus anybody else, whoever was deemed not to have voted for president Mwai Kibaki was harassed and even killed.

Mungiki, whose peripheral meaning is translated as the multitude, is a Kikuyu youth movement that began in the plains of Ng’arua and Sopili in Nyahururu around 1987. Over the years, it mutated into a militia for hire by the political elite.

Thiong’o, who is a landlord in Kangemi, told me there is a silent face-off between the Kikuyus and Luhyas: “Right now, we are not talking to each other [meaning no discussions that may lead to politics] until August 8. But we are ready for them. If they think they will be voting Raila so they can be paying reduced rent… they are in for a rude shock. We landlords have agreed that in the very unlikely event Raila is sworn in as president, we would rather burn the houses than see these western people dictate to us the rents we charge.”

Still, with all his bravado and ethnic machismo, Thiong’o nevertheless whispered to me that once he has voted, he will be gone to his rural home in Murang’a to follow the vote count among his relatives.

“Kikuyu tenants too have been changing houses and moving closer to their fellow kith and kin,” said a tenant I interviewed recently. “If you may recall, there used to be a village called Kijiji cha Chawa (the louse village), sandwiched between Huruma and Mathare 4A, that was largely inhabited by Kikuyus. Many of them were killed [during the 2008 post-election violence]; those who were able to escape, ran away, and whatever was left was destroyed youth from the Luo community.” Today, what used to be a slum dwelling is a playing field connected to Huruma by a footbridge.

“The Kikuyu landlords are aware of these movements, but they will not talk about them openly,” said a landlord from Huruma, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “In fact, some of them are abetting these movements, as they also prepare to secure and safeguard their property.” Once bitten, twice shy. Landlords who burnt their fingers in the violence following the 2007/8 general election have come up with ingenious ways of ensuring their steady income is not interrupted and their property not destroyed.

“Kikuyu landlords, the majority of whose tenants are Luos, have evolved a symbiotic relationship with them. The tenants have been given the freedom to pick one of their own as the buildings’ caretakers, collecting rent on the landlords’ behalf, as they also ensure that the buildings are well maintained.”

In the Kibera slum, quiet movements have been taking place. For instance, Kikuyu families living in Gatwekera village, which is largely composed of Luos, have been relocating to Laini Saba village, nearer to their fellow Kikuyus

The horizontal movements have not only been taking place in the northeastern slums of Nairobi. In the infamous Kibera slum, quiet movements have been taking place as the country hurtles towards elections. For instance, Kikuyu families living in Gatwekera village, which is largely composed of Luos, have been relocating to Laini Saba village, nearer to their fellow Kikuyus.

The regrouping of the menfolk along ethnic lines in the major ghettos and peri-urban areas of Nairobi is to create buffer zones, just in case the violence of 2007/8 is repeated. “It is as if you were watching a pantomime: There are a lot of rhythmic motions by silent men, who very well know what they are plotting against each other, but nobody has the guts to stop and say; ‘But why are we doing this to one another?’,” observed my confidant.

Barely 100km northwest of Nairobi, Naivasha, one of the towns in the Rift valley region that was badly affected by the 2007-2008 post-election violence, is witnessing its own vertical and horizontal migrations. Presiding over a memorial service in the town in mid-June, Nakuru Catholic Diocese head Bishop Maurice Muhata observed, “Some families are transporting their children to their rural homes ahead of the election and this is very wrong.”

A cosmopolitan town mainly populated by Kikuyus, Naivasha nonetheless has a minority migrant labour force mostly drawn from Nyanza and western Kenya, who are employed as casual labourers in the large mechanised flower farms in Karagita, Kawere and Kongoni on the Moi South Road. Ten years ago, as the violence spread into the inner towns, Naivasha and Nakuru’s migrant workers bore the brunt of revenge violence by marauding Mungiki youth imported into the towns to murder and pillage the Luo people and their property.

Since the trashing of the presidential petition on March 30, 2013, the silent narrative out there among the opposition’s legion of supporters has been that there is no turning to the (Supreme) Court and there is no crying foul in case their party is (at least to their minds) unfairly defeated yet again. Beginning in 2016, this resolve has been gaining currency, telling opposition supporters that they should be prepared for any eventuality.

WE ARE NOT GOING TO TAKE THIS LYING DOWN

The National Super Alliance (NASA) presidential flagbearer Raila Odinga seemed to feed into this urgency when in an exclusive press interview at his home in Nairobi’s Karen suburb, he told the interviewer on January 28: “I have said clearly, we are democrats. We would like to have a fair game. If we lose unfairly, we will not accept… We are saying we are not going to take it lying down this time round.”

“Roundi hii kutawaka nare” (this time round, there will be real fire), a fiercely loyal supporter of the opposition told me last year. “Ile gwoko ya 2007, itakuwa chai ya saa nne,” (The violence that erupted in 2007 will be likened to ten o’clock tea). Middle-aged and going by the moniker Roger Millah, the Luo man declared, matter-of-factly: “Electoral theft cannot be allowed to continue unchecked; this thing has to be sorted out once and for all.”

For Florence Kanyua, a vocal Bunge la Mwananchi (people’s parliament) activist from Nairobi, there is no mincing of words: “Every Kenyan is hoping for a peaceful election, but a peaceful election does not mean we should not demand justice and when that justice is taken away, we are expected ‘to move on’, just because, apparently, Kenyans love their peace. This time, Kenyans will say no monkey business. The governing coalition has been warned that it cannot steal the election once again and hope to get away with it.”

Kanyua was addressing her fellow Bunge members, who have created their own space at the cross-section of Mama Ngina Street and City Hall Way, right in the CBD centre. Here, the members congregate in the evenings from 6.pm-8.30pm to dissect the day’s political happenings. When we met, she had a special topic she wanted to lecture them on.

“The church does not know what it’s talking about, because it has been overtaken by events. Its peace message is tired and useless — what we need is justice, not peace,” her tenor voice boomed, reverberating beyond the ethnically diverse group of men who surrounded her. “In 2007, when the peace message would have made sense, the church was nowhere to be found or heard; it had compromised itself by taking sides in the politics of the day.”

The result, Kanyua told her crowd, was that the church lost its credibility because it had become partisan. “Kenyans were killed in a church in Burnt Forest in Eldoret — where was the voice of the church when Kenyans needed that voice most? It was nowhere. Why? Because the church became part of the post-election violence. The church ought to know Kenyans are a peaceful people: what they are craving for is justice. The church should not douse us with its peace rhetoric.”

The truth of the matter is Kanyua was not saying anything new. Months after a peace agreement had been ironed out between President Mwai Kibaki and opposition leader Raila Odinga in February 2008, with the help of former United Nations secretary general Kofi Annan, I had a long chat with a Diocesan Catholic priest from the Archdiocese of Nairobi.

Every Kenyan is hoping for a peaceful election, but a peaceful election does not mean we should not demand justice and when that justice is taken away, we are expected ‘to move on’, just because, apparently, Kenyans love their peace. This time, Kenyans will say no monkey business

“Why did the Catholic Church — the largest, most influential and powerful church in the country — fail Kenyans in the 2007-2008 post-election violence?” I asked him. “The church did not fail Kenyans in 2007/8,” said the priest, who spoke to me on condition that what we were discussing was strictly between a parishioner and his confessor. “The post-election violence was the culmination of a church that had ceded its moral authority to the state five years earlier. The church was reaping the fruits of its lack of moral indignation and its overt indulgence of a state that had come to regard the Catholic Church as its ruling partner.”

In the 1990s, the Catholic Church had thrown it weight behind a fledging opposition that was continually harassed by former president Daniel arap Moi. When, in 2003, Mwai Kibaki, the compromise opposition candidate, floored Moi’s protégé Uhuru Kenyatta, the Church celebrated with the new President.

After all, he was a Catholic, “But fundamentally, the then head of the Catholic Church in Kenya, retired Archbishop Ndingi Mwana ’Nzeki, was a friend of Kibaki,” the priest reminded me. “The Church literally went to bed with the state. A criticism of the government was considered to be a criticism of the president himself.”

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH LOOKED THE OTHER WAY

The Catholic Church is very hierarchical, just like the military – you must obey your superiors without question. “Individually, a priest is a mere cog in the institutional, powerful wheel that is the Church. You do not want to mess with it — you can be easily crushed.” The priest told me president Kibaki indulged the Church and did its bidding. In return, the Church unquestioningly looked the other way, as his government took the Church’s support for granted, and engaged in wanton corruption.

“I knew the Church had completely lost its moral compass, when in the lead up to the 2007 general election, our brother priests in Central Kenya openly canvassed for president Kibaki from the pulpit.” The priest told me that some of his fellow priests went beyond their call of duty to invite politicians to politick from the pulpit itself. “The Church had become the state and the state had become the Church.

“Should it shock anyone that when political violence threatened to blanket the country, the Catholic Church did not stand up to be counted?” asked the priest. “The post-election violence aftermath divided the Episcopal Conference of Bishops so much that they never could agree on anything for a long time. The violence had divided the bishops on ethnic fault lines with great bitterness and so too the legion of priests working in the thousands of parishes spread all over Kenya.”

The priest nostalgically told me how he longed for the days when the Church was led by the late Michael Cardinal Maurice Otunga. “Yes, he was conservative, yes, he was pro-establishment — but pro-establishment with checks and balances.” The priest told me even president Moi knew his limits with Cardinal Otunga. “In his reign, as cardinal, he never allowed the Church to be divided along ethnic lines and would never have allowed any politician —including president Moi — anywhere near the Catholic Church pulpit.

“How we miss the pastoral letters penned by the Episcopal Conference of Bishops then: They were direct, powerful and spoke to the heart of the nation. After addressing the nation and the government through the letter, Cardinal Otunga would direct the letter be read and communicated to the Catholics parishes all over the country.”

Two days before Raila and his NASA team went to campaign in Tharaka Nithi County in Meru on June 16, 2017, I visited a printing press on River Road in downtown Nairobi. The press, owned by a Tharaka man, was incidentally printing flags and posters to be used in NASA’s rally. Out of the blue, he said: “Hawa watu wamezoea kuiba kura za Raila, wajaribu tena… kutawaka moto. (These people who are used to stealing Raila’s votes, we dare them to try again….they will be starting a fire).”

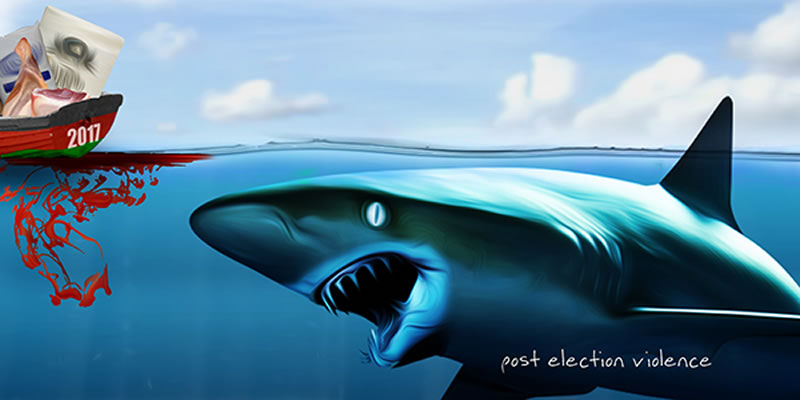

THE SPECTRE OF VIOLENCE HAUNTS KENYA

Although I have been conducting my interviews in formal English and Kiswahili and very often in Sheng, not even that lyrical “rebel” language spoken in the ghettos and county council estates of the Eastlands area aptly captures what Kenyan writer Yvonne Owuor calls the third official language of Kenya — the language of silence (after English and Kiswahili). As these “political” realignments in the ghettos of Nairobi take place silently, but openly, in anticipation of an ominous “uncertainty” a spectre could be haunting Kenya — the spectre of violence.

“Uncertainty is not a good experience,” a Kenyan university don told me recently. “Since 2007, uncertainty in the Kenyan political terrain has come to mean a foreboding of violence.” We were having a sumptuous lunch in an exclusive Nairobi club, where the nouveau riche pontificate on the shifting sands of Kenyan politics far from the madding crowd.

The Kikuyus living in the North Rift would be well advised to take leave before August 8. They live there at the mercy of the Kalenjins. They should not wait to be collateral damage

“Let us not us not kid ourselves,” said the professor, who asked that I should not reveal her designation. “After the post-election violence of 2007-2008, our national politics has never been the same again.” The don, a Kikuyu, teaches at Kabianga University in Kericho County. “I timed my 2017 annual leave to fall in the month of August. I am not taking any chances.”

She observed how her boss, a Kalenjin professor, had, with a light touch, teased her about being timid. “I thought now we are on the same side?” She said she laughed about it, but still presented him with her leave form. “It is better to be safe than sorry.”

“I was there when the March 2016 Kericho Senator seat by-election took place,” she explained. “Although it was strictly a family feud, there was an eerie feeling that if matters were to get out of hand, violence would erupt.” Seemingly thinking aloud, she added: “The Kikuyus living in the North Rift would be well advised to take leave before August 8. They live there at the mercy of the Kalenjins, They should not wait to be collateral damage. I mean if things were to go wrong…”

The crux of the matter is that the relationship between the Kikuyus and Kalenjins in the Rift Valley region has always been fragile and frosty. Since the orgy of violence that visited the North Rift after the 2007 general election, the area has remained a powder keg of bottled up emotions.

The International Crisis Group addresses the professor’s fears in its latest report, Kenya’s Rift Valley: Old Wounds, Devolution’s New Anxieties. It quotes a governance expert saying: “The alliance between the Kikuyu and Kalenjin following Jubilee’s 2013 election victory lulled many into believing historical foes were on an ‘irreversible’ course to overcoming animosities. Yet Rift Valley reconciliation remains superficial. What we have is negative peace … calm.”

This false calm seems to have reared its ugly head once again in Eldoret town and its environs. After the shambolic and bruising Jubilee Party nominations in April, the battle for the Uasin Gishu County governor’s seat has boiled down to a fight between the incumbent Jackson Mandago and Zedekiah Bundotich Kiprop alias Buzeki, a middle-aged, lean, bespectacled nouveau riche, who is running on an independent ticket and looks poised to snatch the seat from Mandago.

Feeling the heat from Buzeki, the exiting governor has resorted to the time-tested politics of us versus them in his bid to fend off the younger contestant, invoking the lingo of “aliens amid our people.” Mandago and his allies have been sending a menacing warning to outsiders who must know their place or else… vacate the county forthwith.

The aliens being referred to here are the Kikuyus, who are mostly to be found in Eldoret town itself and in its satellite towns such as Turbo. In Turbo, most Kikuyus are concentrated in Huruma ward, the most populous ward, so much so that the Member of the County Assembly is also a Kikuyu. Ditto Market ward in Eldoret town. It is populated by Kikuyu people, most of whom are traders. Market ward’s MCA is also a Kikuyu.

Why do the Kikuyus in the North Rift find themselves, once again, in the shadow of the valley of death — even though “they are on the same side with the Kalenjins?”

When the violence of 2007/8 erupted in the North Rift, Huruma and Market wards were the most affected. No prizes for guessing why.

In 2014, I travelled to Karatina, a market town about 100 km north of Nairobi, on the Nairobi-Nyeri highway, to meet one Njeri from Nyeri town. Njeri had been one the biggest mitumba (secondhand clothes) traders in Eldoret town. She had lived in the town — to be precise, in Market ward — for 15 years. “I had built my business from scratch. Every Eldoret resident knew me as ‘Njeri wa Mitumba.’ I was successful, I had made it. But then the 2007 general election came and everything all of a sudden went topsy-turvy.”

Between sips of cold White Cap beer at Star Bucks Hotel, Njeri narrated to me how on December 30, 2007, her world came crashing down. “The arsonists specifically went looking for my godown. They bayed for my blood. But before they got me, they torched the godown and my Ksh5 million stock went up in flames.”

What saved her life, she told me, was that her Kalenjin friend called her in the dead of the night and asked her to leave the town immediately. “Don’t take anything — just go.”

How has this old man ever wronged us? If Raila led this country, what would happen? Let him now lead so that there can be fireworks. We the Kipsigis people are tired of the chicanery shown to us by these two thugs , Uhuru and Ruto

“I went back to my folks’ place in Nyeri town, where I grew up, with nothing but the clothes I had on.” Seven years later, she was yet to rebuild her life — not so much in terms of capital to start a new life, but that she had yet to adjust to Nyeri life. “Eldoret had been my home. I went there as a determined young girl ready to sacrifice and work my arse off.”

Njeri told me that when, in 2013 Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto teamed up to run for the presidency, she was devastated. “My fellow Kikuyus from Nyeri could not understand me, but then how could they, I had spent my adulthood in the Rift Valley diaspora and that is when it dawned on me that there is a huge difference in how ancestral Kikuyus and diaspora Kikuyus view national politics.”

AN ARMISTICE WRITTEN ON QUICKSAND

As I headed back to Nairobi and she to Nyeri, she stated that political violence will always stalk the Kikuyus in the North Rift. “Have the people who perpetrated the violence ever been punished? The artificial armistice between the Kikuyus and Kalenjins is written on quicksand.”

The rumour in the town is that Buzeki, whose wife is allegedly Kikuyu, will attract the Kikuyu votes – which, if that happens, could be the game changer. The intra-Jubilee Party political squabbles are nowhere near safer for the Kikuyu community in the tumultuous North Rift than they were in the lead up to the December 2007 general election. “We will count the votes Buzeki gets and if he gets 100 votes, then a certain community will have to move out of Eldoret,” Mandago is quoted to have said.

Yet something more sinister allegedly took place in Eldoret that went unannounced. Early in February 2017, when the IEBC opened voter registration centres countrywide, Mungiki youth were purportedly shipped from towns such as Nairobi and Nakuru to register in Eldoret North constituency, Deputy President Ruto’s former constituency. It did not take long for the local community to realise there were “strangers” among them. According to reports, the young men were thrown out of town and the story did not reverberate beyond Eldoret.

All this despite the fact that Deputy President William Ruto, whose International Criminal Court case once threatened to tear up the manuscript on which the Kikuyu-Kalenjin truce was written, has stayed united with President Uhuru Kenyatta.

The International Crisis Group report notes that the “dismissal of Ruto’s case [in April 2016] brought particular relief in Rift Valley, where uncertainty over his fate was beginning to sow division within the governing coalition. Claims Kenyatta was not doing enough to get his Deputy President off the hook fed Kalenjin mistrust, heightening fears of renewal of inter-communal tension.”

Yet, with a section of the Kalenjin nation seemingly throwing its support behind the opposition coalition NASA, it is likely that were violence to start, it would consume Bomet County and the adjoining towns of Kericho and Sotik, says Ali Abkula. Abkula was The National Alliance (TNA) political director in the lead-up to the 2013 general election. TNA is the political vehicle that President Uhuru used to ascend to power.

Bomet County Governor Isaac Ruto in April 2017 joined the NASA Four — Raila Odinga, Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka, Musalia Mudavadi and Moses Wetangula — to form the Pentagon. Ruto is a Kipsigis, the largest and the most populous of the nine Kalenjin sub-tribes. They mostly inhabit the South Rift and for the better part of Jubilee rule, have been complaining of how they have been receiving the short end of the stick from the Jubilee government, even after voting for the coalition en masse in 2013.

On the weekend of June 17-18, Ruto addressed a rally in Nakuru town and hit out at both President Uhuru and his Deputy William Ruto (no relation). Reminding them that the country does not belong to two tribes — the Kalenjins and Kikuyus — he accused them of sending the country down the drain. He told the crowd what the electorate wanted was justice and not war. “Sisi hatutaki vita….tunataka kupiga kura kwa amani ndio tupate haki… wasitutishe. (We do not want war…what we want is to vote peacefully and get justice…we will not be threatened).”

Among the Kikuyu speakers, an eight-minute video clip has been making the rounds through the social media, warning them of relinquishing power to the opposition

The community’s beef with the senior Ruto, the Deputy President, who himself is a Kipsigis, but grew up among the Nandis of Eldoret after his parents migrated north in the late 1960s, is that he dished out all the plum state jobs to the Nandis and neglected to fulfil the development promises he lured them with.

An elderly Kipsigis man, having tea in a kibanda (roadside shack) in Kericho town in early June, got into an argument with fellow tea customers about the forthcoming elections. In a fit of anger and fury, he stood up and said: “Saa yote huyu mzee…. Saa yote huyu mzee… Huyu mzee ametukosea nini? Kwani Raila akiongoza itakuwa nini? Wacha sasa aongoze moto iwake. Sisi Kipsigis tumechoka na uongo wa hawa majambazi wawili (Every time this old man….Every time this old man. How has this old man ever wronged us? If Raila led this country, what would happen? Let him now lead so that there can be fireworks. We the Kipsigis people are tired of the chicanery shown to us by these two thugs (Uhuru and Ruto).”

Determined to slice off a chunk of the huge Kalenjin consolidated vote, Governor Ruto has stoked real fear in the heart of the Jubilee coalition. “Sometime early this year, the Kipsigis elders met and gave the Governor the go-ahead to form an alliance with the opposition NASA,” an elder from the community said to me.

On June 17, Emurua Dikirr outgoing MP Jonathan Ng’eno was in Narok North attending a funeral service. Looking visibly agitated he asked the congregation: “Kwani tukipigia Raila kura tutakufa? (If we choose to vote for Raila, are we going to die?)”

“The intransigency and the digging in by both Jubilee Party and NASA is ominous,” says Ali. “It does not augur well for the country. Like in the 2007 general election, the August 8 election involves the unseating of an incumbent.” Such a scenario, he says, is always fraught with overtones of political violence.

On the same day Ng’eno was telling his constituency they could vote for the opposition leader Raila Odinga, Raila himself was telling the Maasai people in Kajiado County to not dispose of their land hastily. The comment was quickly hijacked by Jubilee Party aficionados who used this remark to paint Raila as a warmonger. No sooner had Raila finished uttering those words than leaflets were already in circulation in the county.

“We woke up the following day to find leaflets strewn everywhere and pinned on electricity poles saying that ‘foreigners’ such as Kikuyus and Kisiis should vacate Kajiado,” said Mzee Kanjory who lives in Corner Baridi. Mzee Kanjory said that many of the leaflets were dropped off in the Pipeline area. Pipeline is the stretch between Isinya and Kiserian towns.

“This area is really cosmopolitan; Kikuyus, Kisiis, Luhyas, Luos, Maasais all have invested in this area,” said Mzee Kanjory. “It would be a good starting place to foment ethnic tension in Kajiado County.” If violence were to occur in Kajiado, the Mzee assured me, it would be brutal and genocidal.

“This is a county that has been harbouring festering wounds for a long time among the local Maasai people, who, even though they sold their land on a willing-buyer willing-seller basis, still feel they were cheated. It would only take a small trigger to ignite an inferno.”

The forthcoming general election, which is already showing signs of being the hottest contested ever, has put Kenyans on edge. Among the Kikuyu speakers, an eight-minute video clip has been making the rounds through the social media, warning them of relinquishing power to the opposition. Entitled Mt Kenya Group — Ngai Emwena Witu — “God is on our side,” the video is a montage of Kikuyu popular songs carefully selected to evoke ethnic passions, as well as to create a siege mentality among the larger Kikuyu community.

The lyrics disguised as a clarion credo to rally The House of Mumbi — a catchphrase used by ethnic bigots to evoke a sense of emotional oneness among the Kikuyu nation — are a subtle call to arms if the opposition NASA coalition were to wrest power from the Kikuyu.

CALING ALL KIKUYUS

Calling all Kikuyus, wherever they are, to vote for President Uhuru Kenyatta, the jingoism expressed in the amateur production is frighteningly unabashed and unapologetic in its war cry: “We must protect Uthamaki (political king) at all costs. We must stop the opposition from capturing power by all means. We will not accept to be defeated, because defeat does not exist in our lexicon. Therefore, the House of Mumbi cannot be defeated.”

In a bizarre request to the Inspector General of Police Joseph Boinnet, the Kiambu County governor seat candidate and Kabete MP Ferdinand Waititu asked him to deploy only Kikuyu police officers to the county. “The deployment is the only way our people will effectively communicate to the police and therefore boost security,” said Waititu on June 29.

With a fidgety ruling coalition seemingly under siege from a resurgent opposition, determined to snatch power from a faltering coalition — but one with immense powers of incumbency — we could be headed for a civil war if the election is not properly conducted.