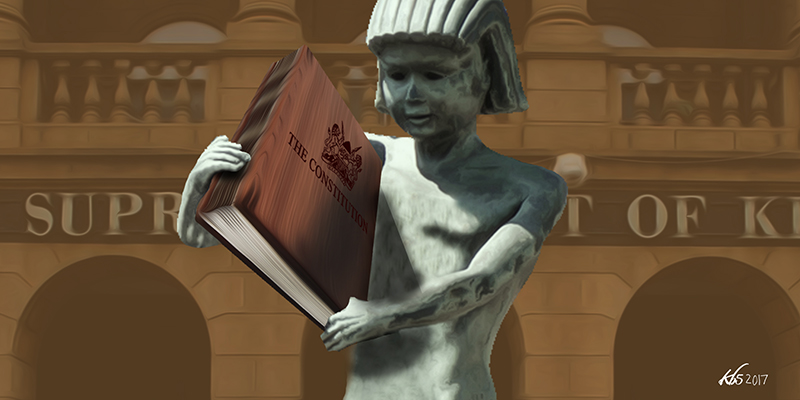

2010 – 2020: Ten years of constitutional resilience

Most of the commentary about the first ten years of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 have largely revealed a constitution under siege. The assault on the constitution has intensified in the last eight years during Uhuru Kenyatta’s presidency. This is not surprising since it is an open secret that Uhuru has little regard for the constitution, for the rule of law and for constitutionalism.

Worse, in the last few years, formal organised opposition – a significant guard rail of the constitution – crumbled. With the rapport between Uhuru and Raila Odinga through the so-called handshake, the opposition, a significant buffer that previously gave Uhuru’s government a bit of pause on assaulting the constitution, was eliminated. It is therefore not surprising that Uhuru and Raila are making a concerted effort to amend the constitution largely to suit their personal and political interests.

There is no doubt that the constitution has performed sub-optimally in the last ten years, especially because of the antagonism from state officers and agencies. Still, it is remarkable that it has survived the first ten years of its birth, despite the consistent and sustained assault on it by Uhuru’s regime.

But how much longer can the constitution endure the intentional, well-orchestrated and nefarious scheme to kill it? Will the constitution last long enough to see the passing of another decade? Even if it does, what state of ruin will it be in? Are there obvious things that will accelerate its death or strengthen its resilience?

Why constitutions die

Professors Zachary Elkins, Tom Ginsburg and James Melton, who have conducted empirical studies on the endurance of constitutions, identify the key factors that help predict how long a constitution will last. However presented, the factors boil down to two things: the design of the constitution and the environment under which the constitution operates.

There are different ways to expand on each of these factors, but first a critical statistic on the average age a constitution. In their analysis of national constitutions enacted since 1789, Elkins, Ginsburg, and Melton found that national constitutions only lasted an average of seventeen years. Yes, 17. This is a depressing fact, especially when one looks at how much effort and time goes into bringing about a new constitution. For example, the 2010 Kenyan constitution was the result of more than thirty years of active and persistent citizen and civil society agitation. And this is not appreciating that even the initial constitutional tensions immediately after independence were the first signs of the need to bring about a home-grown and more responsive people-centred constitution.

Operating environment and design of the 2010 constitution

No doubt, the ruling class has poisoned the environment in which the 2010 constitution has operated since its promulgation. It started with President Mwai Kibaki who tried to subvert it by usurping the powers of constitutional agencies through the illegal nominations of the Chief Justice and the Director of Public Prosecutions. The courts had to step in to restrain him. Many times, he violated the transitional provisions of the constitution by failing to follow the procedures that required him to consult with the Prime Minister before making significant decisions affecting the state. Worse, and despite working under a constitution that stipulated national values of leadership to include inclusion, Kibaki continued to perpetuate nepotism and tribalism in the manner in which he chose high-level public officers.

But while Kibaki was bad at priming the environment under which the constitution operated, his successor, Uhuru, has been worse. Although Kibaki regularly flouted the constitution, he was often quick to walk back whenever he was called out on his transgressions – in a sense confirming that the constitution was the ultimate decider. Unfortunately, this has not been the case with Uhuru, who obstinately disregards the constitution, consistently ignores court orders and actively encourages other public officers to do the same. Worse, he has perfected many of the vices that the constitution intended to eliminate – centralisation of power; rule by law; unmeritorious and unprocedural appointments; corruption; fanning nepotism and tribalism; undermining decentralisation, name it. His has deliberately and fully contaminated the environment under which the 2010 constitution has operated for the last eight years.

But while Kibaki was bad at priming the environment under which the constitution operated, his successor, Uhuru, has been worse. Although Kibaki regularly flouted the constitution, he was often quick to walk back whenever he was called out on his transgressions – in a sense confirming that the constitution was the ultimate decider.

Perhaps what has helped sustain the constitution is its design. No doubt, the 2010 Constitution was designed with the full awareness that the political elite will attempt to undermine it. A few illustrative design issues will make the point much better. These include the provisions on defending the constitution, including empowering any citizen to go to court and to petition other institutions, such as Parliament, to enforce it; and strong separation of power provisions, including setting up an independent Judiciary which can invalidate anything that is done by anyone outside the law. Other provisions include the creation of independent offices and commissions that are intended to be the front line enforcers of the constitution. Finally, and perhaps the most critical design aspect on the endurance of the constitution, is its provisions on amendments, which are complex, onerous and mostly impossible without critical national consensus.

Saving the constitution from premature death

If one was to obsess about the seventeen years statistic on the average life span of constitutions, it would suggest that the 2010 constitution is already past its mid age, with a great likelihood it will die before its 20th anniversary. However, the short life of national constitutions begs a much more important and forward-looking question – what could help save the 2010 constitution from possible early death?

I identify three things that need to be put into place if we are to save the constitution from premature death, and especially if we wish to see the constitution survive the next decade unscathed. Even if the constitution is amended, how can we ensure that the amendments will benefit Kenyans and not the political elites? Three things need to happen: (i) rebuilding confidence in the constitution; (ii) finding critical formal actors that believe in and can defend the constitution; and (iii) an implementation that delivers tangible constitutional goods to citizens.

Rebuilding confidence in the constitution

Perhaps the greatest threat to the constitution is the waning sense of confidence in it. There are fears that the constitution is taking too long to find stability. But we should have foreseen and prepared for this.

Kenya’s political life has been built on a scaffolding of simplistic narratives of messianic moments. It started with the struggle for independence, with a narrative that the coming of independence would obliterate Kenyans’ political and economic misery. Then there was the expectation that a change of guard from Jomo Kenyatta to Daniel arap Moi would be a turnaround opportunity for the country – and for a moment, Moi seemed to have fed that hope, especially by releasing political prisoners and developing a high-sounding but essentially hollow “Nyayo philosophy” of peace, love and unity. All this soon buckled under the weight of the lie for which the simplistic and feel-good “philosophy” was constructed.

The next messianic moment was in 1991 with the deletion of Section 2A from the 1969 Constitution which prohibited multipartyism. However, with the opposition politicians endlessly feuding, that messianic moment was also quickly lost.

Then in 2002 the country seemed to pin all its hopes for rejuvenation in the seemingly nationalistic alliance led by Mwai Kibaki. But Kibaki quickly killed the budding sense of nationalism as soon as he took over as president by denigrating the role that Raila Odinga and other key political actors were to play in the government. This disillusionment would – in less than five years – bring a people, who had been regarded as the most optimistic in the world in 2003, on the verge of civil war because of ethnicised political contestations.

But even the devastating events of the post-election violence of 2007/2008 were not sufficient to dissuade Kenyans from believing that there was still a chance for a magic wand moment. So, when the 2010 constitution was promulgated, many believed that this was the tool that would, with speed, transform Kenya politically and economically. The 2010 constitution was the ultimate political-legal messiah.

In many ways, placing overbearing hopes on the new constitution was not overly irrational. When fully implemented, this constitution has the potential to transform Kenya into an egalitarian society that places human dignity and social transformation for all at the centre. Devolution, even with all its infirmities in design and implementation, offers snippets of evidence of this. But because of the constitution’s social transformation potential, the political and economic elites, who thrive on an environment of lawlessness, have invested their last penny to undermine it.

But even the devastating events of the post-election violence of 2007/2008 were not sufficient to dissuade Kenyans from believing that there was still a chance for a magic wand moment. So, when the 2010 constitution was promulgated, many believed that this was the tool that would, with speed, transform Kenya politically and economically.

Worse, those hell-bent on immobilising the constitution have done so by conjuring up and feeding a narrative that it is an idealistic and unrealistic charter. Because they wield power, they have used their vantage points to counter most of the salutary aspects of the constitution. Uhuru Kenyatta’s consistent and contemptuous refusal to follow basic requirements of the constitution in executing the duties of his office, including his endless defiance of court orders, stands out as the most apt example here.

Yet all this is calculated to create cynicism among Kenyans about the potency of the constitution. Hoping that the cynicism will erode whatever goodwill Kenyans have towards the constitution, the elites believe that they can fully manipulate or eliminate the constiution entirely and replace it with laws that easily facilitate and legitimise their personal interests, as did Jomo Kenyatta and Moi.

Still, this constitution is unique because of the participatory manner through which it was developed and the fact that it is a consensus document for the people and not – as was with all past constitutions – a pact between the political and economic elites. The people’s goodwill towards it still seems inordinately firm.

Regardless, to give the constitution more authority, it is important to eliminate the growing sense of cynicism towards it and regenerate confidence amongst Kenyans about its the potential as a social transformation charter. A significant part of that regeneration must come from recruiting new critical formal actors who believe in and are committed to the implementation of the 2010 constitution.

Recruiting formal supporters of the constitution

The 2010 Constitution of Kenya survived the last ten years largely because of the Judiciary, some Chapter 15 Commissions and independent offices (especially the now defunct Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution), the Office of the Auditor General, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, and the first Salaries and Remuneration Commission (SRC). It has also survived because of a few vigilant citizens – leading among them being Okiya Omtatah Okoiti. Equally, there have been numerous civil society organisations that have sustained citizens’ mobilisation for the support of the constitution and relentlessly pushed for its implementation.

Ironically, two of the primary state organs created by the constitution – that is the Executive and Parliament – have posed the greatest threat to the constitution. Worse, Uhuru has been on a nefarious campaign to weaken even the key formal institutions that have been pro-constitution – especially the Judiciary and Chapter 15 commissions and independent offices. Presently, he has found a way to fully capture Chapter 15 institutions through a warped process of hiring commissioners and heads of independent offices to capture those institutions, thus isolating the Judiciary as the only state agency that is largely committed to constitutionalism.

But it is too much (and quite unfair) to expect the Judiciary to be the only state agency that shoulders the burden of trying to keep the constitution alive. Kenyans must find ways to generate sustained support for the constitution from other state officers and agencies.

If the constitution has a chance of surviving the next ten years, it must have additional state agencies who unequivocally believe and support it. The starting point must be the Executive. There is no doubt that if the next president (post-2022) is not a strong defender of constitutionalism, the 2010 constitution will likely irretrievably wither. Even if the document survives, we will not only have the situation that Prof. Okoth Ogendo aptly described as “constitution without constitutionalism”, we will be left with just a shell – a constitution without any pulse.

Why is the president so critical? Although the 2010 constitution dispersed power as much as possible, it still gave the resident a significant responsibility. Article 131 states that the president is the symbol of national unity. This requires him or her to be the first at respecting, upholding and safeguarding the constitution and the rule of law, as well as promoting and enhancing the unity of the nation. Hence, while there are many checks on the powers of the president, in practice he still wields significant legal, political and symbolic influence on all aspects of governance. If the next president leads at disrespecting or showing utter contempt for the constitution – as has been the case with Uhuru – the chances that the constitution will survive will be negligible.

Following the promulgation of the constitution in 2010, Parliament showed mixed results on its conviction on constitutionalism. But for all its faults, the 10th Parliament did a lot to help set up the infrastructure that the constitution needed for its implementation. This included laws and approval of persons to critical offices – including the Chief Justice and Chapter 15 commissioners who strongly believed in the rule of law. The then Speaker of Parliament, Kenneth Marende, also helped greatly to give Parliament some institutional integrity.

Regrettably, that cannot be said of the two current speakers of Parliament or the parliamentarians of the 12th Parliament. In fact, in 12th Parliament we have seen an institution that is so keen to supplicate at the feet of the president that it has fully eroded the enormous institutional power the constitution gives it and has fully compromised on its role as a check on the Executive.

Hence, for the constitution, what will be worse than a president who does not believe in constitutionalism will be the continuation of the unholy alliance between Parliament and the Executive. Yet, if Parliament was to fully appreciate its power of fostering the entrenchment of constitutionalism and its primary role of being the critical check on the Executive, the 2010 constitution would not only have a chance at survival, but would also likely deliver the tangible transformation it intends.

In a nutshell, it is unlikely that the Judiciary alone will be able to save the constitution in the next decade. In fact, it is unlikely that left as the lone ranger that fights for the constitution, the Judiciary itself will survive or manage to maintain any modicum of professionalism and independence. All this is to say that 2022 is a critical year for the 2010 constitution. A great deal of its survival largely depends on the persons who becomes president and who are the speakers in Parliament.

Implementation of the constitution must yield tangible goods

This takes me back to constitutional cynicism. Having executive and parliamentary leadership that believes in the 2010 constitution and constitutionalism will be key – but citizens’ patience of trying to relate a constitution to their economic and social welfare is running thin. This is not because people have no ability to do so since, even with all its infirmities, they have been able to see how the patchwork implementation of devolution has brought about tangible transformation.

This is sad for at least a couple of reasons. First, the national government has been undermining devolution either directly or indirectly by undermining county leadership, by failing to devolve sufficient funds or by undermining county functions through function-hogging or recentralisation.

In a nutshell, it is unlikely that the Judiciary alone will be able to save the constitution in the next decade. In fact, it is unlikely that left as the lone ranger that fights for the constitution, the Judiciary itself will survive or manage to maintain any modicum of professionalism and independence.

Second, the leadership has also undermined the most critical pillar of the 2010 constitution, which is on social and economic transformation. There are few constitutions in the world that have detailed what the state must do in order to bring about equitable social transformation as does Kenya’s constitution. Yet, the government has refused or failed to follow through on the roadmap provided by the constitution, opting instead on ad hoc, politically inspired, unsustainable and mostly badly thought-out and short-lived programmes designed to benefit only a few.

The operating environment that will save the constitution

And it is back to where we started – constitutional design and the operating environment as the two overarching factors that dictate the survival of a constitution. For the last ten years, the constitution has operated under a toxic environment – with most of the toxicity coming from the Executive. Parliament (especially the 11th and 12th) surrendered most of its authority to the Executive and hence failed miserably at defending the constitution. The complete capture of all the independent offices and commissions by the Executive has mostly left the Judiciary as the sole state institution struggling, albeit now in a wobbly way, to defend the constitution.

Constitutional design contributed greatly to the survival of the 2010 constitution in the last ten years. But design alone will not save it for the next ten years. Whether it dies or not will now largely depend on whether our next heads of the Executive and Legislature are believers of constitutionalism and whether they are keen to provide the constitution with the enabling environment that the people intended for it to thrive.