Recently the matter of Kenya’s national indebtedness has gained wide coverage in the media, not least in a presidential roundtable with the press on December 28th, 2018. In my opinion, our nation is grossly indebted, and in fact we are in a de facto state of emergency as far as our nation’s finances are concerned. I hope to demonstrate this fact below, and to suggest what options we have for dealing with our indebtedness.

Several indicators for measuring national indebtedness exist, such as Debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (Debt:GDP), debt per capita, etc. Probably the most widely-used indicator is the Debt:GDP ratio. This particular metric is so obfuscatory and misleading that it is not inconceivable that it was actually developed to mask the truth about national indebtedness the world over.

When we as individuals want to borrow salary-backed loans from banks, the banks attempt to assess our ability to pay off these loans by reviewing our payslips, sometimes going back 3 to 6 months. This effort is calculated to answer just one question: what is our take-home pay? In doing this, the banks are assessing our credit-worthiness, which helps to reduce the risk of default.

At the national level, however, this abundance of caution is thrown to the wind. The use of the Debt:GDP ratio to measure national indebtedness means that a country’s ability to take on more debt is assessed on the basis of its GDP. At an individual level, such an assessment would approximate assessing our ability to pay off salary-backed loans based on our gross pay. In fact, it is much worse: it is more like assessing an individual’s ability to pay off a loan based on how much revenue he generates for his employer. Even if such a company is just breaking even, the revenue an employee earns his employer must necessarily exceed his salary, or else that organisation would be unable to meet its operational costs, such as rent, electricity and other office expenses. Put another way, the revenue an employee generates pays a lot more than his salary). Since GDP attempts (poorly) to measure the total value generated by all the economic activity in a nation, to use it as a basis for measuring whether a country has room to borrow is patently unwise simply because not all the value created in a nation’s economy is available to pay a nation’s debt.

The revenue employees generate and the value an economy generates (GDP) are analogous in that both are measures of value created. However, whereas the revenue produced by employees accrues directly to their employers’ GDP, it does not so directly accrue to a nation. For example, after a loaf of bread has been produced in a country, that loaf is not submitted to the government, yet its production adds to the nation’s GDP. For this reason, even a revenue-based definition of employees’ income does not properly approximate the absurdity of using GDP as a measure of national income on which to assess indebtedness because not all of GDP accrues to the nation as income.

By masking true indebtedness, therefore, the Debt:GDP ratio encourages wanton borrowing. This works in favour both of fiscally irresponsible (or worse, corrupt) governments and of predatory lenders…

What is the net effect of all this? The more broadly a lender can define a borrower’s income, the larger the proportion of that borrower’s true income that will flow out as loan repayments, and the more the borrower’s assets stand at risk of repossession as collateral. This is what has happened to us as a nation. When we consider further stratagems like rebasing our GDP, which had the effect of increasing our GDP by 25% at a stroke, it can be seen that by nominally increasing our GDP the illusion was given that our nation was able to take on even more borrowing than before, opening the gates to yet more lending.

By masking true indebtedness, therefore, the Debt:GDP ratio encourages wanton borrowing. This works in favour both of fiscally irresponsible (or worse, corrupt) governments and of predatory lenders, both private and multilateral (the line between private and multilateral lenders is far thinner than is generally believed). We do not pay debt out of GDP. We pay debt out of our national revenues. The more revealing and honest measure would be debt-to-national revenue. For the same reasons of honesty and clarity, it is prudent to narrow the definition of national revenue down further to tax revenue, thereby eliminating grants, donations, monies realised from the sale of public assets, and other incidentals from the discussion.

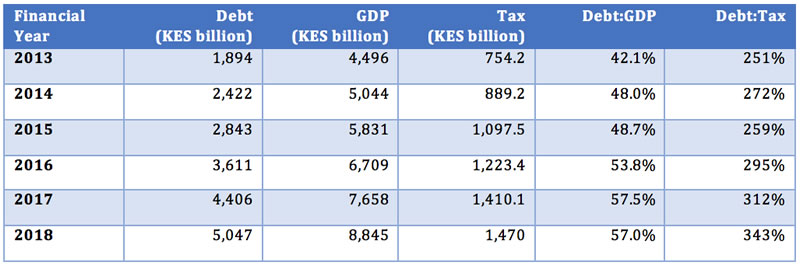

The problem – from the viewpoint of irresponsible governments and predatory lenders, of course – is that once we do so, the scales will fall off our eyes and it becomes apparent just how much of our nation’s money is going towards servicing our debt. According to the national Treasury, our national debt, which stood at Sh1.894 trillion in the financial year (FY) 2013, had grown to Sh5.047 trillion by the end of FY 2018, a growth of 269 per cent.

In 2013, however, the government collected a total of Sh754.2 billion in taxes. The implication is that our Debt:Tax ratio stood at a whopping 251 per cent in that year. By 2018, although revenue collections had grown to Sh1.47 trillion, our debt had grown much faster, so much so that our Debt:Tax ratio in the FY 2018 stood at 343 per cent.

Our GDP in 2013, according to the same report, was Sh4.496 trillion, meaning our Debt:GDP ratio was 42.1 per cent in 2013. In 2018, our GDP was Sh8.845 trillion. (This suggests that our GDP has been growing at a compounded annual growth rate of 14.49 per cent, which would be news to most Kenyans; the effect of rebasing our GDP can now more clearly be seen.) These figures imply our Debt:GDP ratio in FY 2018 was 57 per cent.

In 2013, however, the government collected a total of Sh754.2 billion in taxes. The implication is that our Debt:Tax ratio stood at a whopping 251 per cent in that year. By 2018, although revenue collections had grown to Sh1.47 trillion, our debt had grown much faster, so much so that our Debt:Tax ratio in the FY 2018 stood at 343 per cent. In other words, if the Government did nothing else but pay off our national debt – if it did not pay teachers, doctors, nurses, the army, and the police; if it did not provide medical supplies; if it bought no textbooks; if it did not construct one metre of road or railway; if it did not construct one hospital room or classroom or police post – it would take us about three and a half years to pay off the national debt.

This situation is untenable. National Treasury data indicates that in FY 2018 we spent Sh459.4 billion servicing our debt. By that measure, debt repayment was the single largest item in our nation’s expenditure, exceeding our expenditure on transport infrastructure (Sh225 billion), health (Sh65.5 billion) or education (Sh415.3 billion). In other words, we are spending more paying off our debt than we are spending providing good transport for our people and good treatment for our sick – combined.

A day of reckoning is soon coming for our beloved country, on which day we shall realise that indeed, as per the Holy Writ, “…the borrower is slave to the lender”, and that debt (even if the money is used well, let alone if it is actively misused as we have done) is the tool of the neo-colonialist. It will become starkly apparent that by a system of multilateral and international debt, there is a sense in which foreign powers have been able to be perhaps as extractive of our nation’s wealth as they were when they were in power as our colonial masters. There is in fact a very real sense in which the colonial powers never really left. The only major change is that China is now on the list of our foreign masters.

We have already seen multilateral lenders like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) force our government to impose VAT on fuel. This is not the first time this happened. In 2013, when our debt was less than half what it is now, the IMF backed changes in our VAT law that would have imposed VAT on milk and medicines, claiming that “…the changes in the law [would] put Kenya in line with other modern VAT regimes in the world by simplifying the way it operates while reducing the number of exempt items.” Although the Cabinet did not impose VAT on milk and medicines, other items, such as textbooks, periodicals and magazines, did not escape the taxman’s levy. The press reported that our national port in Mombasa was used as a security for the loan that was used to construct the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR). These are not isolated bellwethers of the dire situation our country finds herself in: the Daily Nation recently reported that we will require Sh1.04 trillion to service our debt in FY 2020. Where will it come from?

We must now examine possible solutions to what is clearly a monumental problem. The truth is this: debt can be dealt with either by paying it, or by not paying it. National debt can be repaid through austerity programmes and/or by the realisation of collateral. A nation may avoid repayment by pursuing debt forgiveness; defaulting on our sovereign debt; and/or overseeing a managed default on our sovereign debt.

Options for paying our national debt

Austerity programmes

Since the national debt can only be paid out of taxes, an escalation of the national debt can only result in an austerity programme. Austerity is a term that follows a very well-worn path of giving nasty, anti-common man policies honourable names (this is what is called “Economese”). Simply put, austerity necessitates the redirection of large portions of tax receipts away from normal government expenditure (including mission-critical social expenditure like health and education, and away from development expenditure) in an effort to pay off the debt. The Merriam-Webster dictionary describes austerity as “enforced or extreme economy”.

The fact that Kenya is – whether it has publicly announced it or not – well up the austerity road is evidenced by the earlier observation that debt repayment is the single largest item in our nation’s budget. By the time our lenders and leaders decide to announce that we are in an austerity programme, we will have been in one for years.

To examine where this road leads, we must turn to Greece. That nation has been locked in austerity’s deathly embrace for the better part of a decade. An Al Jazeera article notes that the austerity programme in Greece was occasioned by over-borrowing (sound familiar?) in the years leading up to the global financial crisis, which was exacerbated by a rise in rates occasioned by that crisis. In order to keep paying government salaries and finance public services, Greece had to accept an initial loan of EUR110 billion from its Eurozone partners and the IMF. To pay off this loan, the country was compelled to institute radical austerity measures. How did that go?

In August 2018, the Guardian summarized Greece’s experience thus:

The European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund loaned Greece a total of €289bn ($330bn) in three programmes, in 2010, 2012 and 2015.

The economic reforms the creditors demanded in return brought the country to its knees with a quarter of its gross domestic product (GDP) evaporating over eight years and unemployment soaring to more than 27%.

The fundamental contradictions between the envisaged outcomes of austerity and its outcomes in reality are also the reason we find multilateral lenders talking out of both sides of their mouths, first imposing these programmes, and then sheepishly admitting that they have not worked. The IMF, for example, actually produced a report stating that it made notable failures on its first rescue package to Greece.

Greece teaches us, if we will listen, that the time is likely to come when Kenya will be unable to pay government workers’ salaries and will not be able to fund essential public services, such as security. At this point, the Government of Kenya will be forced to take on yet more borrowing to prevent a mass uprising. These “rescue packages” will be offered on grossly usurious terms, terms that the government will have no choice but to accept. Then, in a strange twist of irony, the very people upon whom the initial injustices were visited will do the lenders’ marketing for them by way of a civil uprising. From then on, our nation’s expenditure will be “supervised” by these lenders, not to help the Kenyan people, but to ensure that these lenders are paid. These are doomsday scenarios, and I find it difficult to even write them. Yet it can get worse – and has, elsewhere in the world.

Realisation of collateral

Realisation of collateral is a method of debt payment that is as old and as basic as Shylocks. It is difficult to recall a time when national debt was collateralised to the extent that has happened in the recent past. It appears that the realisation of collateral appears to be the favoured method of China for collecting debt. For our case study on this, we must turn to the nation of Sri Lanka, as the New York Times reported:

Every time Sri Lanka’s president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, turned to his Chinese allies for loans and assistance with an ambitious port project, the answer was yes.

Yes, though feasibility studies said the port wouldn’t work. Yes, though other frequent lenders like India had refused. Yes, though Sri Lanka’s debt was ballooning rapidly under Mr. Rajapaksa.

…Mr. Rajapaksa was voted out of office in 2015, but Sri Lanka’s new government struggled to make payments on the debt he had taken on. Under heavy pressure and after months of negotiations with the Chinese, the government handed over the port and 15,000 acres of land around it for 99 years in December [2017].

There are examples closer to home. In December 2018, the US National Security Advisor, John Bolton, sensationally claimed that China was about to take over the Zambia Electricity Supply Corporation (ZESCO), which is Zambia’s version of Kenya Power & Lighting Company, before KenGen and Ketraco were hived off. Although this rumour was strongly refuted by Zambia’s presidential spokesman, Mr Amos Chanda, Mr Chanda did admit that Zambia owes China US$3.1 billion in debt. In Africa that kind of statement from that kind of person often means the figure is much higher; indeed, some sources have placed the figure at US$6.4 billion.

In 2017, Zambia’s police force had to scrap plans to hire eight Chinese nationals following a public outcry. Zambians were concerned about having to salute a Chinese national in their own country. It is also true that in November 2018 police arrested over 100 residents in Kitwe (the country’s second-largest city) who were protesting the alleged sale of the Zambia Forestry and Forest Industries Corporation (ZAFFICO). There is a possible sub-plot here: Mr Bolton’s claim may mean that the IMF and Western allies are worried that they are losing their grip on the Zambian nation to China.

Options for not paying our national debt

In advocating for the non-payment of national debt I am not advocating injustice or dishonesty for this reason: “The government” is not a nebulous entity separate from the people. The government is the people. When the government borrows, it is the people who are borrowing; when the government pays, it is the people who must pay; indeed, it is their taxes that are used to pay.

As can be seen from the foregoing, over-borrowing, poor governance and/or the mismanagement of public funds can lead to adverse effects, not on “the government”, not on the lenders – even private lenders – but on the people. The stark truth is that austerity rarely, if ever, aids recovery – unless by recovery we mean the recovery of lenders’ money.

As can be seen from the foregoing, over-borrowing, poor governance and/or the mismanagement of public funds can lead to adverse effects, not on “the government”, not on the lenders – even private lenders – but on the people. The stark truth is that austerity rarely, if ever, aids recovery – unless by recovery we mean the recovery of lenders’ money. Austerity is a creditor-oriented policy, not a people-oriented policy, and it fails because cuts in government spending result in reduced consumption, unemployment and lower tax receipts. Yet tax receipts are what are needed in order to pay off the debt. The realisation of collateral (the other solution) is nothing but the seizure of a people’s land

There exists, therefore, a moral case for non-payment, which is this: that the betrayal of a people by its ruling class through the accumulation of a debt whose benefits the people never realised should not be visited upon the class of the ruled, who pay the debt. On this point, therefore, I am advocating for justice, not injustice; and for honesty, not dishonesty.

Debt forgiveness

Debt forgiveness is not a new concept; it is in fact a biblical concept. The concept of Jubilee meant that every 50 years, during the eponymously-named Jubilee year, all debts were written off, all enslavement ended, and everyone was allowed to return to whatever ancestral lands that they might have had to give up because of an inability to pay back debt. A thorough examination of the wisdom and justice of this law would take up a solid chapter in a good book; suffice it to say that it acted like a legislated revolution, resetting the kind of gross national inequalities that US Senator Bernie Sanders is grappling with – for the price of a trumpet blast.

Our gross national indebtedness means – or rather, dictates – that we pursue debt forgiveness, because we simply cannot pay back everything we have borrowed. The problem is that we are not considered a poor country any more – not even a low-income country. We are now a middle income nation, and precedent shows that debt forgiveness is the preserve of highly indebted poor countries. Our pleas for debt forgiveness, therefore, are quite likely to fall on deaf ears. Further, a significant portion of our national debt is owed to China and China, Sri Lanka might whisper, is not a nation one asks for forgiveness.

A note of caution must here be sounded: only 15 or so years ago, Zambia had its debts wiped clean under the IMF’s Heavily Indebted Poor Countries scheme. The same country then took “less than a decade” to run up fresh debt of 59 per cent of GDP, buying million-dollar fire engines and constructing roads twice as expensive as those of her neighbours.

A strategy of debt forgiveness is, therefore, useless in the absence of enforced legislation to ensure that future over-indebtedness and/or wastage is prevented. A law preventing the government from tying up more than 10 per cent to 15 per cent of the average tax collected in the previous five years on debt servicing would be a very good place to start. The laws preventing wastage and theft of what we actually do borrow do exist, but require radical enforcement.

Default on sovereign debt

There exist exceptional circumstances in which nations default on their national debt. These times are usually presaged by significant external shocks or political ones, such as when Fidel Castro took over in Cuba in 1959, and simply defaulted on outstanding Cuban debt. The bonds on which he defaulted are in default to date.

Reference is often made to the Argentinian default (and one must be specific) of 2001. In 1998, Argentina’s economy entered a deep recession. The IMF’s by now predictable solution, of course, was austerity. Over the course of the following two years, it became increasingly clear that the toxic mix of an artificially fixed exchange rate, a steadily worsening balance of payments deficit (imports exceeding exports) and mounting debt, among other factors, meant that Argentina would never be able to pay off its debt.

Then the people began to protest, with increasing vociferousness, against austerity. When in December 2001 the IMF realised that default could not be avoided, it held back previously promised “support” so that the government was left without any external funding. Bank runs and riots followed: at one point the country had five presidents in ten days. Finally, on December 24, the country defaulted on a US$ 100 billion debt. This led to a social crisis of epic proportions, characterised not least by rampant unemployment.

Sovereign defaults of this nature tend to be devastating and ought to be avoided. The social cost ends up being far too high, even if one is a Castro leading a non-conformist Cuba. Firstly, in order to teach other would-be defaulters a lesson, lenders make an example out of one. Secondly, the world has become too interconnected for us to make ourselves a pariah state for any length of time: globalisation is a source of many ills, but it can help us as well, for we have a surplus of labour that we can offer the world (among other competitive advantages).

Managed default on sovereign debt

The way we might want to do it is the way Ecuador did it between 2007 and 2009. The then President Rafael Correa stopped payments on bonds that the country had taken out, and established a “debt audit commission” to conduct an audit on the country’s debt, which at the time was using up 38 per cent of the government’s budget. The purpose of this audit was to establish the “legitimacy” of the debt.

This was a brilliant first step. Firstly, it brought to the forefront the moral injustice of a people’s having to pay loans from which they never benefitted. Secondly, the reason given for the initial default was a moral one, as opposed to a financial one (even though the financial reasons lurk menacingly in the background). The genius behind the debt audit was that it was for establishing the morality (and not merely the affordability) of the public debt. Such a debt audit commission in Kenya – objective, apolitical (in a local sense), staffed with technically qualified, patriotic individuals and with an ability to trace the flows of borrowed funds – would likely produce spectacular results.

The way we might want to do it is the way Ecuador did it between 2007 and 2009. The then President Rafael Correa stopped payments on bonds that the country had taken out, and established a “debt audit commission” to conduct an audit on the country’s debt, which at the time was using up 38 per cent of the government’s budget. The purpose of this audit was to establish the “legitimacy” of the debt.

Ecuador’s debt audit commission found that the debt was illegitimate based on the manner in which negotiations were conducted. (The reasons for which debt can be illegitimate are myriad: here in Kenya, the factors would range from non-existence of the assets ostensibly purchased with the debt, overpricing of assets that do exist, payment of bribes and kickbacks, and lack of public participation and parliamentary approval, etc.) Arising from the stopped payments, and from the public establishment of the illegitimacy of the debt, the value of the bonds on the open market plunged. The Government of Ecuador then tendered to repurchase the bonds at 30 cents on the dollar. On the basis of the auction results, the government then offered to buy back the bonds at 35 cents on the dollar, expecting to retire at least 75 per cent of the bonds. Ninety-one per cent of the bonds were so retired in June 2009, that the government paid off its public debt for about a third of what it was worth and, according to President Correa, saved US$ 300M (Sh30 billion) per year in interest payments.

The Ecuadorian solution has an elegance that only simplicity gives. However, its success needs to be assessed against the backdrop of an important contextual factor: the retirement of the country’s debt happened at a time when markets were in the throes of the global financial crisis. Investors, therefore, were under pressure to liquidate their assets. Further, how successful this method would be as regards Chinese debt is anyone’s guess: simple and easy are vastly different things.

That said, the process presents a blueprint for any government that is ready and willing to ease the burden of over-indebtedness and is an option and a strategy this country should pursue – before it’s too late.