It has become clear that for now, post the handshake between Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga in March, that our immediate politics is undergoing important possibly tectonic succession related shifts. Just over a week ago, government bulldozers destroyed the homes of 30,000 Kenyans in the sprawling Kibera informal settlement to make way for a planned road. This quite understandably caused profound consternation among rights advocates. Politically the Kibera demolitions demonstrated the intensity of the handshake thus far in Kenya’s political firmament. Kibera is one of the most concentrated pools of opposition supporters in the country. Yet the demolitions proceeded there without much in the way of stones or tear gas canisters being thrown. This would have been unimaginable in the recent past where its political cost would have been counted in dead bodies and hospitalized victims. But while the country is distracted by high profile corruption-related arrests and overdue demolitions of illegally constructed buildings, more significant governance processes have quietly ramped up.

Every decade Kenya carries out a census of its population. It is an essential development-planning tool as well as critical to the demarcation of constituency and other boundaries. The next one is due this coming year. The demarcation of boundaries is due to be carried out by the Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) that conducted the two failed general elections last year. At the start of this month the Council of Governors held a consultation and issued a firm statement asking for a third revenue sharing formula between the central government and the Counties. They made the point that the 2009 census was fraught with problems and a new formula was needed post the anticipated 2019 census.

Censuses across the continent are intensely politicised affairs. Ethnic numbers have implications on political identity and legitimacy; the dishing out of patronage and government spending in general. The ‘right to steal’ for elites is partially derived from this ethnic math because the unspoken rationale is that people in public office steal for their tribesmen. These kinds of calculations even led to the interesting decision that saw Kenya’s entire Asian community officially designated a tribe last year). In the 1989 census, our Asians were classified under: ‘Kenyan Asian’, ‘Indian’, ‘Pakistani’ and ‘Other Asian’. Presumably, it was the ‘Kenyan Asians’ who became tribe No.44. Last week in the Oshwal Community, an important section of Kenyan Asians, when faced with the imminent demolition of the sprawling Oshwal Center that’s built atop a river in Nairobi, appealed to even the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on social media to help save it. Like many owners and tenants of illegal properties, they protest that they have all the legal documents for the properties. I shall return to this argument later and the way Kenyans have mastered the art of legalising the immoral, the unconstitutional and plain anti-people absurdities.

The demarcation of boundaries is due to be carried out by the Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) that conducted the two failed general elections last year. At the start of this month the Council of Governors held a consultation and issued a firm statement asking for a third revenue sharing formula between the central government and the Counties. They made the point that the 2009 census was fraught with problems and a new formula was needed post the anticipated 2019 census.

Africa’s most populous country Nigeria carried out its first reasonably comprehensive census in 1952/3. Another was conducted ten years later in May 1962. The results, however, were challenged politically. Another was therefore carried out in 1963 whose results were contested in the Supreme Court with some arguing that it had been an exercise in ‘negotiation rather than enumeration’. Another census in 1973 was not published on the grounds of a falsification of figures for political/ethnic advantage. Another census in 1991 left out questions of ethnicity and region in order to ‘improve accuracy and response’ during the census process. The last broadly accepted census was carried out in 2006. The next one was due in 2016 but still has not taken place. Population numbers are also ethnic numbers and ethnic numbers deeply inform questions of political competition across Africa. Interestingly, the machinery of conducting a census was most robust in countries with a large white settler community such as Zimbabwe, Kenya and South Africa. In these cases, the census is also an instrument of political control and manipulation.

***

Analysts contend that at the end of the 1980s Chinese leaders saw something in Sub-Saharan Africa that all the continent’s other global interlocutors did not. That Africa’s population of roughly 850 million would reach over 2 billion by the middle of this century. By 2010 there were over 1 billion Africans. Of the 2.4 billion people projected to be added to the world’s population between 2015 and 2050 1.3 billion will be Africans. By 2100 Africa’s population will be between 4 and 5 billion people – a full third of humanity. If people of African descent on other continents such as the Americas, Caribbean etc – Brazil and USA in particular – are included, 40 percent of the world’s people will be of African descent by the end of the century.

Censuses across the continent are intensely politicised affairs. Ethnic numbers have implications on political identity and legitimacy…The ‘right to steal’ for elites is partially derived from this ethnic math; the unspoken rationale is that people in public office steal for their tribesmen.

Africa will have not only the world’s most rapidly growing population but also its most rapidly urbanizing. Managed correctly, this is the kind of combination that creates a demographic dividend that has helped drive prosperity in other societies.

These trends are driven partly by rising fertility rates in Africa as they fall in other parts of the world and even where they have declined in Africa they are doing so more slowly than in other continents. Still, Africa’s population is the most youthful and there has been consistent debate over the past decade as to how this demographic dividend can be tapped. In Kenya’s case, 75 percent of the population is below the age of 35.

***

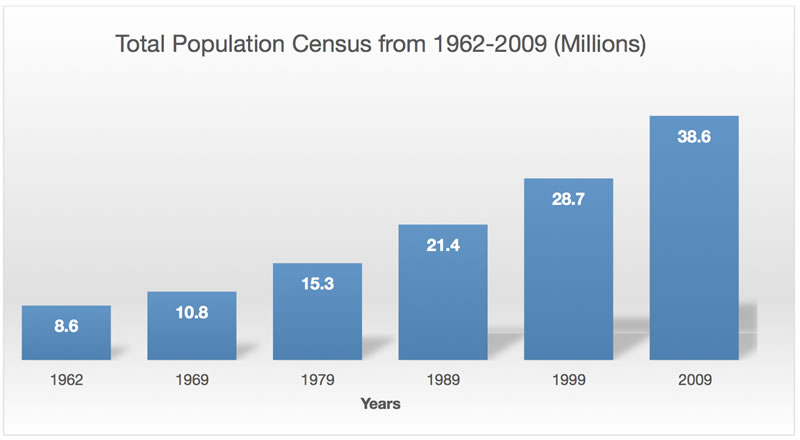

Kenya’s population has grown from 8.6 million in 1962 to 11 million in 1969 when a census was conducted; to 15.3 million in 1979; 21.4 million in 1989; 29 million in 1999 and around 40 million in 2009.

Population by tribe in 1969

Population by tribe in 1969

Population by tribe in 1979

Population by tribe in 1989

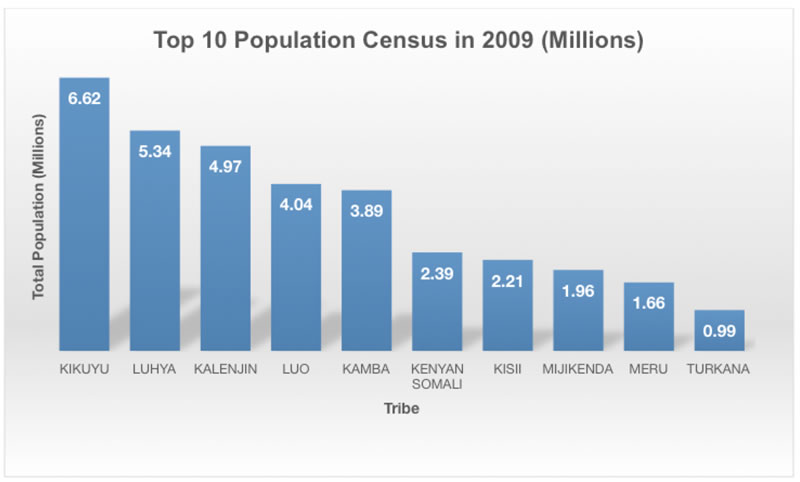

Population by tribe in 2009

Source: Kenya Bureau of Statistics

In the 1979 census the Kalenjin sub-groups, Nandi, Kipsigis, Tugen et al. were amalgamated into one identity on paper and formed part of the basis of President Moi’s politics from then on. The 2009 results were so controversial that at first the government disowned the results from entire parts of northern Kenya including: Lagdera, Mandera East, Mandera Central, Mandera West, Wajir East, Turkana North, Turkana South and Turkana Central districts.

Source: Kenya Bureau of Statistics

Source: Kenya Bureau of Statistics

The two heavily affected communities here were the Turkana and Somali. The then Minister for Planning and current Kakamega Governor Wycliffe Oparanya tabled evidence in parliament that in some of the regions the population figures had been ‘inflated’ to 2.35 million people instead of the actual population size of 1.3 million. Indeed, the population in North Eastern Province had risen three-fold in a decade Analysts argued that considering regional mortality and birth rates the higher numbers didn’t make sense and in some regions would have meant women giving birth twice a year between 1999 and 2009. The higher figures had political import of course, for some of the reasons articulated above. The 2009 data, for example, meant that in a single decade the Somali community had overtaken the Kisii in size. The minister’s review of the census data was challenged in court where the High Court upheld the census results.

Nigeria carried out its first reasonably comprehensive census in 1952/3. Another was conducted ten years later in May 1962. The results were challenged. Another was therefore carried out in 1963 whose results were contested in the Supreme Court with some arguing that it had been an exercise in ‘negotiation rather than enumeration’. Another census in 1973 was not published on the grounds of a falsification of figures for political/ethnic advantage. Another census in 1991 left out questions of ethnicity and region in order to “improve accuracy and response” during the census process.

By the start of this year, a consistent debate based on population growth indicators among the Somali community had kicked off exploring the implications of the Somali becoming one of Kenya’s ‘Big Four’ ethnic groups in the coming two decades. Ironically, it is frowned upon in most African cultures to count people like animals and therefore doubly offensive to be speaking of the ‘Big Four’ tribes in the same way we speak of the ‘Big Five’ types of wildlife in Kenya. But such are the political imperatives around being one of these big tribes in this era of ‘tyrannies of numbers’ determining political prospects, that cultural misgivings aren’t allowed to hinder this trajectory. Like the building owners complaining that their properties are being demolished despite all the legal papers being in order, the census carries similar fiat power. Once the numbers are published that’s it! It doesn’t really matter if they are true or not but they have significant political and economic implications.

The 2009 results were so controversial that at first the government disowned the results from entire parts of northern Kenya…The two heavily affected communities here were the Turkana and Somali. The then Minister for Planning and current Kakamega Governor Wycliffe Oparanya tabled evidence in parliament that in some of the regions the population figures had been ‘inflated’ to 2.35 million people instead of the actual population size of 1.3 million. Indeed, the population in North Eastern Province had risen three-fold in a decade…in some regions this would have meant women giving birth twice a year between 1999 and 2009.

The highly problematic 2009 census that ended up in court opened the eyes of our political class to this fiat power of the census. The political benefits that accrue from manipulation of a census are now manifest. All the more so in this era of a constitutionally devolved system of government. This partly explains why the governors have already invested heavily in the conduct of the 2019 census. It also raises the possibility in the future of census processes by negotiation more than enumeration.

Research by Juliet Atellah

Related Links

- Fate of constituencies that did not meet population criteria in limbo

- 27 constituencies likely to be scrapped next year

- How North Eastern figures went wrong

- Kenya growing at a million people a year

- Court declares disputed 2009 census results valid from 8 sub-counties in Mandera and Garissa counties

- Population numbers: Somalis race to join big four

- Kenya begins contentious census

- Census and the question of tribe

- Council of Governors pushes for third revenue sharing formula