That a major contest has kicked off between the US and China over their influence in Africa is now abundantly clear, an integral part of the monumental spat between the two superpowers that blew out into the open under President Trump — partly articulated in America’s 2017 National Security Strategy — but whose essentials are clearly being retained by the Biden administration. China is now considered America’s most significant geopolitical competitor and threat, a posture that is reciprocated by Beijing.

Still, it is also obvious that the US is racing to catch up with a China that has dramatically deepened and expanded its relations with Africa since the early 2000s. Ironically, just as the US was checking out of Africa in terms of trade and development and focussing instead on security — and in particular on the so-called “war on terror” — China shifted gear, especially through its giant Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). According to the conservative American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, China has made a total value of US$303.24 billion in investments and construction in Sub-Saharan Africa since 2005. Indeed, by 2019 one in five major infrastructure projects in Africa was financed by China and one in three was being constructed by Chinese companies. China is now Africa’s biggest trading partner and, under President Xi Jinping, the country has rapidly expanded its cultural, social, military and other relations with African countries. In typical Chinese style, this scale-up has been both huge, efficient and rapid.

In East Africa, it is estimated that 55 per cent of all large-scale construction projects are undertaken by the Chinese who also finance a quarter of them. There has been considerable controversy about the extent to which these projects have contributed to a deepening debt crisis on the continent. The opacity and alleged corruption that surround the accumulation of this debt have also been the cause of deepening concern for policymakers and citizens alike. That said, the infrastructure projects align most closely with the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) — currently our biggest “existential project” as Africans. The relationship between Africa and China is complicated. Indeed, relations with all great powers are complex and difficult for developing countries.

The Chinese model

A majority of African countries are aspiring democracies in one form or another. This democratisation stated after the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and by 1995, multiparty democratic constitutions had been promulgated across the continent. The US was a prominent driver of this process and at that point, the West’s push converged with the will of a majority of Africans exhausted by the single-party regimes and dictatorships that had ruled since independence. Today we can agree that the quality of this democracy varies considerably from country to country.

What is increasingly referred to as the “China model” is most obviously not a liberal democracy. All serious polling done by respected organisations such as Afrobarometer confirms that a majority of Africans continue to favour democracy — despite its messiness — over other forms of governance. I should think that this is in part because between independence and the early 1990s, Africa tried a wild assortment of authoritarian models of governance. These were stifling at best and disastrous at worst, especially when led by military cabals who had taken power through violent coups.

By 2019, one in five major infrastructure projects in Africa was financed by China and one in three was being constructed by Chinese companies.

The freedoms that have come with our democracies have in turn become embedded in our broader governance DNA, with our young population unable to conceive of a time when their basic freedoms of thought, speech, association, movement, etc., could be dramatically curtailed. And yet, the “China model” of an authoritarian system that combines a high level of state capacity to deliver public goods such as health, education, etc., to the majority of its people rapidly and on a vast scale cannot be dismissed off-hand.

On the African continent, the Rwandan and Ethiopian models have been compared to the Chinese model. The engagement with China, including its controversial debt-related aspects, has been transformative, especially in regard to the development of critical infrastructure. This cannot be argued with. And this transformation has taken place with unprecedented speed, changing skylines across a continent which has some of the world’s fastest growing cities and the world’s youngest, most rapidly growing population.

Still, the opacity and corruption that sometimes seems to typify the accumulation of commercial debt has been particularly troublesome in a range of developing countries around the world. This is still playing out and African countries are in the middle of a delicate diplomatic balancing act between a risen China, a giant and often thin-skinned partner, and a West that is now in aggressive competition with China. We are caught in between. Western nations are also increasingly vociferous in their complaints about human rights abuses in China. The human rights situation vis-à-vis minorities such as the Uyghurs of Xinjiang Province and the peoples of Tibet has for decades been the source of intense advocacy among human rights activists. The recent governance overhaul backwards in Hong Kong and apparently upcoming one in Taiwan have caused similar distress. Understandably, African policymakers have been profoundly circumspect about joining in these calls. This is despite the fact that African states have over the last 30 years gradually become less tolerant of gross human rights abuses on the continent. Coups are generally a no-no in this day and age, and a state that deliberately seeks to destroy an ethnic group would cause even the usually politically judicious African Union to voice strong opposition. This is in part because orchestrated mass violence against particular groups in one country inevitably spills across our fake borders. The 1994 Rwandan genocide was, and remains, profoundly chilling.

China has been steadfast in its policy of non-interference in the governance of other nations, a stance which is deeply appreciated by an Africa that is finding its voice. Supporters of democracy point out that this approach can sometimes end up propping up some of the most incompetent and dictatorial regimes on the continent. The West has its list of similar clients too though. Suffice it to say that China also retains currency among African elites because it has never been a colonial power on the continent despite China’s Admiral Zheng He (Cheng Ho) and his fleets visiting the East African coast several times between 1405 and 1433. China’s engagement with Africa back then contrasts starkly with Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama’s blood-soaked expeditions in the region from 1497 as he sought a plunder route to India. From the 1950s onwards, China also contributed significantly to African liberation struggles, often in direct opposition to the US and its allies.

*********

From the language and tone over the last few years, one would be forgiven for believing that the US is ready to adopt a Cold War posture with China. There is nothing that causes greater nervousness among African policymakers than the continent finding itself forced into the kind of stark polarity President George W. Bush encapsulated on the 20th of September 2001 when he told the world, “Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists”. This time around however, the relationship between China and Africa is very different from the one Africa had with the Communist bloc in the period after independence. Whereas ideology and the practicalities of the struggle for independence were at the heart of the Cold War relationship, for African elites in particular, China today is first and foremost a development partner. Besides, the Cold War posture was also generally bad for basic freedoms.

From the language and tone over the last few years, one would be forgiven for believing that the US is ready to adopt a Cold War posture with China.

Part of the challenge the US faces as it ramps up the contest with China is one of perceptions: the “shithole” countries, as President Trump called them, aren’t that shitty to other countries that have travelled the difficult development road we are on. For urbanised African youth with access to the internet, the America they view and read about today isn’t necessarily the one America’s unrivalled soft power juggernaut, Hollywood, portrays. A significant amount of bandwidth is instead taken up watching black people being murdered by a clearly systemically racist police force and the ensuing consequences. However, it is also part of the fundamental dynamism of US democracy that President Biden and his team have made so many progressive policy U-turns since taking office 100 days ago. Since he took office Biden’s administration has overseen the vaccination of over 130 million Americans – half the population!

Africans still overwhelmingly support the democratic model but feel the relationship with China is a win-win for Africa.

Other critical rising powers

While there has been considerable focus on China, India, Russia, Turkey and other rising nations have raised their profiles in Africa as well. They have done so without much fanfare but in a manner that has afforded local elites policy choices that were unthinkable as recently as the 2010s. The Russia-Africa Sochi Summit in late 2019, for example, was part of an accelerated engagement by Russia with Africa over the past decade especially in the extractive sector and military trade. Today Russia is by far the continent’s largest arms supplier, accounting for almost half of all military sales to Africa. In 2019, 12 African ministers of foreign affairs visited Russia, and that country’s long serving minister of foreign affairs, Sergei Lavrov, and his deputy Mikhail Bogdanov, held talks with nearly 100 top African politicians between January and September 2019 alone. Bogdanov is said to maintain sustained intensive interactions with African Ambassadors in Moscow. While Russian policymakers emphasise a deepening of “political cooperation” with Africa, they have indicated heightened interest in economic relations — especially in the extractive sector, agriculture, health and education. The speed with which Russia developed its Sputnik V vaccine was startling and its “vaccine diplomacy” in Africa has been more aggressive and successful than that of any other region. Welcome to our new multi-polar world.

What Africans think of China

As I said, Africans still overwhelmingly support the democratic model but feel the relationship with China is a win-win for Africa — with China winning more of course — being qualitatively different from the relationship with the West.

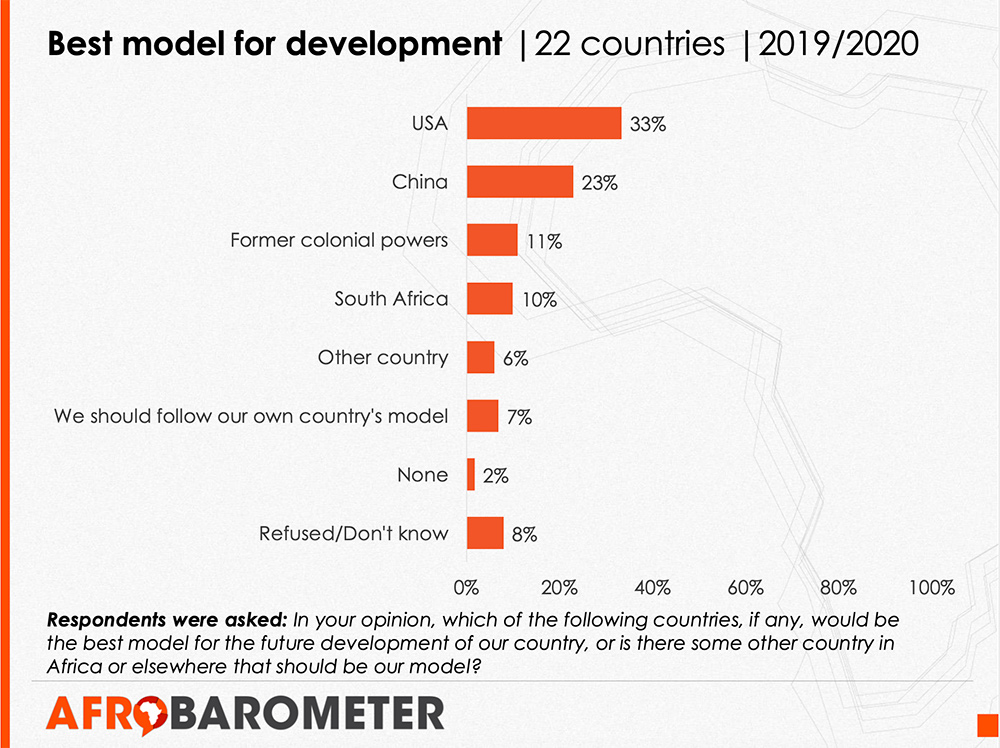

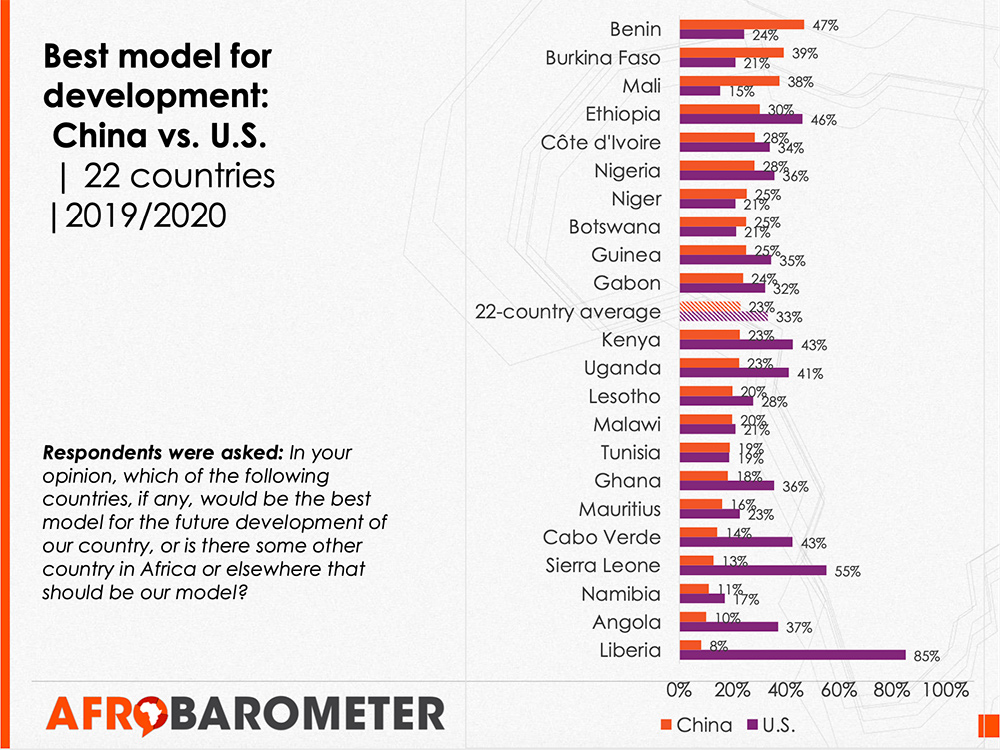

Afrobarometer recently polled African attitudes towards China in 22 countries including Ethiopia, Kenya, Senegal, Ghana, Guinea, Uganda, Nigeria, Angola, Namibia, Zambia among others. In the 22 countries, an average of 33 per cent of those polled thought the US was the best model for development. Twenty-three per cent felt China was the best model of development followed by former colonial powers at 11 per cent and South Africa at 10 per cent. China is emphatically the preferred model for development in Benin, Burkina Faso and Mali. In Liberia, Angola, Sierra Leone and Cape Verde the US is by far the preferred model. In Kenya 43 per cent of respondents prefer the US model compared to 23 per cent who prefer the Chinese model.

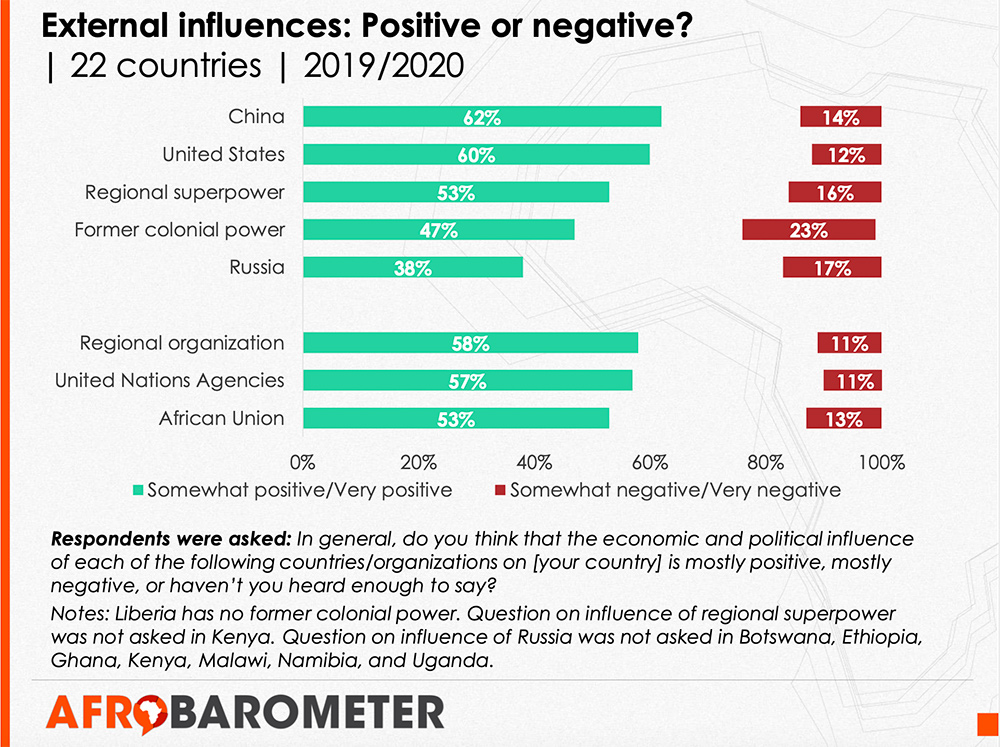

Importantly, 62 per cent of all those polled across Africa felt China has a largely positive economic and political influence on their countries while 60 per cent felt the same for the US.

Indeed, the main takeaways of the Afrobarometer report released in February 2021 include the fact that Africans feel generally positive about China. Significantly, according to the researchers,

“Though new on the block, the attractiveness of China’s development model is second only to the US (especially among older adults). Perceived Chinese influence is on a par with that of the US and well above that of the former colonial powers. Chinese economic and political influence is seen in largely positive terms. Respondents who feel positively about the influence of China also tend to have positive views of U.S. influence as well – suggesting that for many Africans, U.S.-China “competition” may not be an “either-or” but a “win-win” proposition. Popular awareness of China as a lender/giver of development aid to African respective countries is unmatched by the common place talk of Chinese “debt trap” diplomacy in Africa… Be that as it may, a plurality of Chinese loan aware Africans perceive fewer strings attached to those loans/development compared to other donors. Awareness of repayment obligations to Chinese loans/aid is however high among those who know about Chinese loans/aid to their country – suggesting the need for more information sharing about Chinese aid. Indeed, awareness of Chinese loans to the country generally goes hand in hand with expression of concern about the entailed indebtedness…”

*********

The former top Singaporean diplomat, academic and author of Has China Won?, Kishore Mahbubani, argues that the COVID-19 pandemic has confirmed the shift of global power from West to East. He points out that from 1AD until 1820 the world’s largest economies were India and China and that the last 200 years of Western domination are a historical aberration. All aberrations ultimately end. We are living through these tectonic changes. Exciting times. Nothing expresses the contradictions that this means in our daily lives than the way our urban youth use their mobile phones and American platforms such as Twitter and Facebook as instruments of accountability in a complex age.

It is ironic too that the murder of George Floyd by a white policeman that caused such powerful global outrage last year was filmed by 17-year-old Darnella Frazier using her iPhone made in China and uploaded onto American social media platforms not allowed in China, provoking a powerful reaction that continues to reverberate around the world.