Independence, as well as the state it rests on, can no longer even pretend to be able to effectively deliver on the aspirations that gave rise to the anti-colonial movements that birthed it. That process is now over. “Independence” is now obsolete.

If we are to properly understand that, we must not just look at the rise, growth and eventual termination of the Independence Project, but we must also examine the nature of the social class that has operated it, benefitted the most from it and, in the process, also killed it. Any suspicion that this may be an exaggeration will be dispelled by a quick look at some of the “Greatest Hits” produced by this group over the last half century.

There is the tale of a former president of one East African country who, while importing a good number of heavy-duty diesel generators, then ordered his energy ministry to drain a complex of hydropower dams so as to create a country-wide demand for his merchandise via an electricity shortage.

More recently, there is the 2011 story of a Ugandan military helicopter used to slaughter at least 22 elephants and to carry away their tusks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Or perhaps we can talk about the assassination of Gregoire Kayibanda, Rwanda’s first president, whose ouster was followed up by him and his wife being locked in a house and left to starve to death? This was done to him by his successor, Juvenal Habyarimana (he of the ill-fated presidential flight that triggered a genocide), despite them both being “Hutu Power” proponents.

There was also President Mobutu Sese-Seko. And President Jean-Bedel Bokassa. We all know what they did.

One cannot understand the crisis of the neo-colony without understanding the class that feeds off it. Where were these people made, and how do they manage to just keep going?

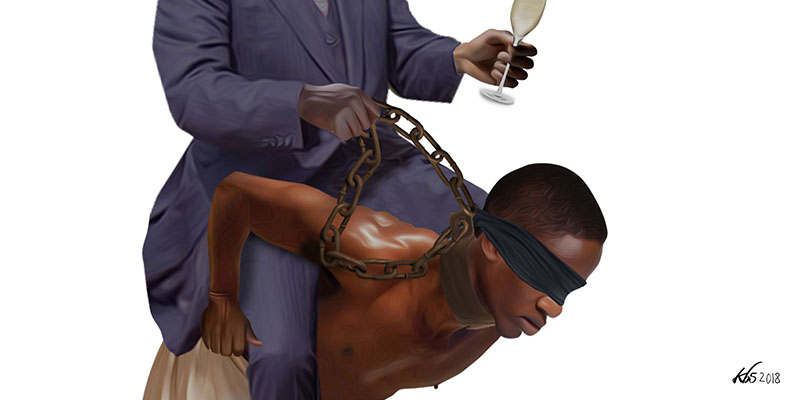

Any idea, however absurd, will be accepted as “normal” as long as there are enough people who benefit from it and who have the power to enforce it. We, therefore, have to start with the industry that birthed the modern world: the transatlantic trade in Africans destined to be enslaved.

The transatlantic slave trade was not a small thing; it lasted over three and a half centuries, creating a particular historical trajectory. The establishment of such a permanent trade converted domestic slavery into an international business and created an intermediary African economic class with a mercenary mindset.

This kind of “intermediary African” came in three broad groups. The first was the home-made, self-appointed agent to foreign commercial needs who enabled the weaponisation and transformation of domestic slavery. Some were bona fide native potentates who saw the chance to get rich and dispose of their enemies. But usually, just to get rich. By 1700, the Kingdom of Ouidah, now in present-day Benin, was exporting nearly one thousand victims a month. From 1704, when King Haffon ascended the throne, the kingdom was considered a bastion for European slave traders who Haffon protected.

The transatlantic slave trade was not a small thing; it lasted over three and a half centuries, creating a particular historical trajectory. The establishment of such a permanent trade converted domestic slavery into an international business and created an intermediary African economic class with a mercenary mindset.

Another type of intermediary African was the enterprising kind who simply emerged from the community; some had previously been traders in other things, while others were mere adventurers. These, like the infamous Kabes (known as “John” to the white slave buyers on the Gold Coast) were known as “Caboceers”, and were described by amateur historian James Pope-Hennessy as “the bane of the European traders’ lives”.

Another group were basically warlords masquerading as native kings or chiefs in order to present themselves as having the authority to capture and sell other Africans. Of note too is how many of these people were identified as “mulattos”, products of encounters between the white slavers and African women on shore.

“Some of the most efficient slave traders of African blood were mulattos and, like the ostentatious Edward Barter of Cape Coast, could read and write and might, to inspire added confidence, even profess to be Christians. Barter (of the apt surname) was reputed in the last decades of the seventeenth century, to exercise more power around Cape Coast ‘than the three English agents together who by reason of their short stay here are so little acquainted with the affairs of the coast that they suffer themselves to be guided by him, who very well knows how to take advantage of them’. Barter, who was legally married in England, had eight other wives and a quantity of mistresses on the coast. He could raise a substantial private army from his own slaves and freemen followers. No one, in Barter’s lifetime, could negotiate with the Cape Coast English without his aid….”

Following the colonial enclosure, a new, less idiosyncratic version of this same instinct came into existence, mass-produced through the (still-thriving) mission school system, and then primed to take over at independence as the “stay-behind”.

After the Independence Project bankrupted itself, these “stay-behinds” ushered in neoliberalism, which then also collapsed in 2008. Now, hanging grimly on to state power, they are looking for a new gig. Enter China.

There is a lot we can see of ourselves from the outcomes of the trade in enslaved Africans. The madness this new class got up to, sanctioned and enabled by the then global powers, created the template for the Africa we live in today:

”…….generally, the motive of both sides of African and European traders alike was the same: commercial greed. Open and unbridled, this greed created at all levels a secret system of bribery as layered as the leaves on an artichoke and far more difficult to strip away. The European companies’ minor employees, as well as their castle slaves, cheated their immediate superiors with considerable cunning to sell human merchandise to ‘separate traders’ or interloping ships. The African traders…cheated their own kings and masters by demanding bribes and dashes, and by obstinately raising slave-prices already fixed at summit palavers between ships-captains and native kings. Both European Agents-General in the castles, and African kings in their sun-baked palace courtyards would strive to circumvent these underhand activities. They would issue edicts and orders to warn their underlings that the cheating had to stop. But did it?”

Substitute the word “slave” for “minerals” or “aid money” and the words “castle” and “palace courtyard” for “foreign investor and “State House”, respectively, and basically you are transported to many an African capital city today.

Welcome to us.

What is perhaps different is how each participant fared in the generations that have followed.

After the Independence Project bankrupted itself, these “stay-behinds” ushered in neoliberalism, which then also collapsed in 2008. Now, hanging grimly on to state power, they are looking for a new gig. Enter China.

Europe got an endowment and built on it. The port city of Liverpool, home to the English football club loved by many a modern African, is a classic example.

A Circumstantial Account of the True Causes of the African Slave Trade, by an Eye Witness, 1797 is a document worth reflecting on in some detail:

“…since the price of slaves on the coast varied little and was seldom exorbitant, their food on the Middle Passage reckoned at ten shillings per head, and their freight at £3.5s., the gain on each slave sold in the colonies was well over thirty per cent. Thus, in the years 1783 to 1793, the net profit to the town of Liverpool on an aggregate of 303,737 slaves sold was almost three million pounds per annum.” (£1 then would be worth about £137 today.)

The account goes on to describe the impact that such a “great annual return of wealth” which, it points out, “may be said to pervade the whole town” had on the city, ”increasing the fortunes of the principal adventurers, and contributing to the support of the majority of the inhabitants; almost every man in Liverpool is a merchant, and he who cannot send a bale will send a bandbox…”

In his book, The Sins of the Fathers, Pope-Hennessey, who I have quoted extensively in this article, explains that:

“At this time in Liverpool, there were ten merchant houses of major importance engaged in the slave trade, together with three hundred and forty nine lesser concerns. Small vessels taking up to one hundred places were outfitted by minor syndicates organised by men of all professions. Attorneys, drapers, ropemakers, grocers, tallow chandlers, barbers or tailors might take shares in a slaving venture –some of them investing one eighth of the money, some a sixteenth, some a thirty second. These investors of modest means were known as ‘retailers of blackamoors’ teeth’. Shipbuilding in Liverpool was gloriously stimulated by the slave trade, and so was every other ancillary industry connected with ships. Loaded shop windows displayed shining chains and manacles, devices for forcing open Negroes’ mouths when they refused to eat, neck rings enhanced by long projecting prongs, thumb screws and all other implements of torture and oppression. People used to say that ‘several of the principal streets of Liverpool had been marked out by the chains, and the walls of the houses cemented by the blood of the African slaves.’ The Customs House sported carvings of Negroes’ heads…”

As for the African traders, they faded away, their descendants becoming part of the later colonised mass, leaving little material legacy of a Liverpool-type magnitude behind and apparently learning very little from their experiences. The Nigerian writer Adeoabi Nuwabani, writing in the New Yorker, exemplifies this. In a revelatory July 15th article titled “My great-grandfather the Nigerian slave trader”, she recounts how her family has sought to come to terms with this legacy through organising Christian prayer sessions among family members scattered across the globe. This is in an attempt to deal with a history of possible family misfortunes that seem to beset them.

“But, in the past decade,” she writes “I’ve felt a growing sense of unease. African intellectuals tend to blame the West for the slave trade, but I knew that white traders couldn’t have loaded their ships without help from Africans like my great-grandfather. I read arguments for paying reparations to the descendants of American slaves and wondered whether someone might soon expect my family to contribute. Other members of my generation felt similarly unsettled. My cousin Chidi, who grew up in England, was twelve years old when he visited Nigeria and asked our uncle the meaning of our surname. He was shocked to learn our family’s history, and has been reluctant to share it with his British friends. My cousin Chioma, a doctor in Lagos, told me that she feels anguished when she watches movies about slavery. ‘II cry and cry and ask God to forgive our ancestors’.”

Nevertheless, the Christian ceremonies described seemed self-absorbed, with no apparent attempt to reach out to the descendants of enslaved West Africans, among whom many of her family members now walk in the Western Diaspora. If the response of a descendant of former slave traders to this history is to cry and cry (and then pray), what on earth should be the posture of one descended from those actually sold?

Africa was left with the embryo of a nimble and agile socio-economic class marked by a culture of cynicism, venality, opportunism and a whole lot of stupidity. This class would to be mass-produced through the mission school system and would rise to political preeminence all over black Africa.

The can be seen first in their lack of originality: they are still chasing after the same over-priced baubles and fake relationships that the African slavers sought. While giving evidence before a 1790-1791 UK Parliamentary Committee enquiring about the trade in the enslaved, one Richard Storey, a naval lieutenant, talked about the “notoriously shoddy quality” of the guns given to the Africans in exchange. “I have seen many with their barrels burst, and thrown away,” he revealed. “I have seen many of the natives with their thumbs and fingers off, which they have said were blown off by the bursting of the guns.”

Africa was left with the embryo of a nimble and agile socio-economic class marked by a culture of cynicism, venality, opportunism and whole lot of stupidity. This class would to be mass-produced through the mission school system and would rise to political preeminence all over black Africa.

Opportunistically, some rich traders would send their children to tour or even study in Europe. And many women of status married “agents” – the white slaving company reps stationed permanently on the African coast to buy and warehouse captured Africans for the incoming ships.

With venality, the enslaving experience left nobody looking good, or even just wise:

“Once, when [a] ship was anchored off a point of land… a canoe approached her bringing an African who styled himself ‘Ben Johnson, Grand Trading Man’. Mr Johnson carried with him a small, kidnapped girl for sale. Once paid, he set off promptly homewards in his canoe; but within ten minutes a second canoe same alongside the ship, paddled by two natives who hurried aboard to ask the Captain whether he had not just bought a little girl. Captain Saltcraig showed them the child, and they precipitately left the ship to return a half an hour later with Ben Johnson tied up in their own canoe. Lugging him aboard, and shouting ‘teeffee! teeffee!’ they offered the protesting kidnapper for sale in his turn. ‘What, Captain? Will you buy me, Grand Trading Man Ben Johnson from Wappoa?” their incredulous prisoner screamed; but Captain Saltcraig showed a Liverpudlian sense of business, as well as one of poetic justice. Declaring that ‘if they would sell him, he would buy him, be he what he would’, he summoned the boatswain to bring irons, and in a thrice Mr Johnson of Wappoa was…fettered to another Negro whom he may have perhaps already sold to Captain Saltcraig.”

So the traders were fully aware that what they were doing was harmful. This is the same situation at play today. Our rulers are fully aware of the damage their actions are causing, but do not care, as long as it does not happen to them or to their offspring. Or so they hope.

Take, therefore, the then famous case of two brothers of the King of Calabar, now in Nigeria, who in 1767 were captured and sold into slavery after a brief internecine conflict. Sold off in the West Indies, they escaped to another plantation in Virginia in America, and after three years there managed to get themselves on to a ship going to the southern English port of Bristol. A British merchant familiar with Calabar then managed to get them off the ship by a court order (of all things), and sent them back to their brother on one of his own ships.

The cynicism can be found in the story of one John Newton (later Reverend and prominent abolitionist, author of “Thoughts on the African Slave Trade” and composer of the hymn “Amazing Grace”), a white Englishman who, before going to become a substantial slaver in his own right, had in 1746 worked as a serf-like apprentice for one already established English trader called Mr Amos Clow. Based on a lime plantation among other white slavers on the Banana Islands off the West African coast, Clow was married to an African woman, whose name Newton could only pronounce as “P.I.” (actually Pey Ey, “the daughter of a powerful chief”).

Newton was to suffer unbelievable and wholly unprovoked persecution from Mrs Clow. Having become too ill to accompany his boss on an inland expedition, Newton was left in her hands, whereupon

“He was given a wooden chest to sleep on, with a log for a pillow. He found it difficult even to get a glass of water, and, when his appetite returned, he was given almost nothing to eat. Occasionally, when ‘in the highest of good humour’, P. I. would send Newton scraps off her own plate, which he ‘received with thanks and eagerness, as the most needy beggar does alms’. Once, when ordered to receive her left-overs from her own hands, he was so weak that he dropped the plate, whereupon the woman laughed and refused to give him any more, although her table was covered in dishes…while still too weak to stand, P. I. would come with her attendants to mock him, and command him to walk about. She set her slaves on to mimic his hobble, to clap their hands, laugh and pelt him with limes and sometimes with stones. When she was not there the slaves would pity him and bring him food from their own slender diet. When he complained to Clow, on his return to the island, the man would not believe him.”

Three centuries of such bloody-mindedness and another century of direct colonial enclosure left Africa dazed, confused, and dominated by a social class bearing a wholly warped mindset. Perhaps we have remained so. Steve Biko did advise us that “the greatest weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed”.

With our new “chiefs” in terms of their antics, from the diesel generator games played with peoples’ lives and livelihoods, to the cynical region-wide looting of the DRC, as well as the South Sudanese blood-letting, one can clearly see this perversity still at work. They are the direct intellectual descents of King Haffon, Ben Johnson, Edward Barter, and the many others whose names have faded away.

Three centuries of such bloody-mindedness and another century of direct colonial enclosure left Africa dazed, confused, and dominated by a social class bearing a wholly warped mindset. Perhaps we have remained so. Steve Biko did advise us that “the greatest weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

And every one of our ludicrous, ridiculous First Ladies is surely the spirit-medium of the soul of “P. I”, the preposterous Mrs Crow.

As for stupidity, I would offer my own 2011 experience of failing to have published what was perhaps the most important story on elephant poaching in our region: hiding behind a series of spurious reasons to play it safe, the decision-makers at the Nation Media Group successfully foiled it.

Why do we put up with them? It is because they have monopolised formally-sanctioned knowledge, state institutions, technical skills, violence, and useful links to the outside world. We are their hostages.

This is what Frantz Fanon warned us about in his essay “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness”. It is what the ANC’s top commander, Chris Hani, also worried about in the run-up to the end of apartheid. What they did not (and perhaps could not) tell is just how this would all eventually end up.

Well, now we know.

We are living it.