If you want to see colonialism alive and well in 2021, one of the first places you should look is Mathare, or any of Nairobi’s informal settlements. These are places where people are still not treated as full citizens, but rather, as sources of cheap labor. Citizens deserve publicly provided or accessible water, electricity, healthcare, education, roads, etc. But the people of Mathare are not treated as citizens. They are treated as disposable.

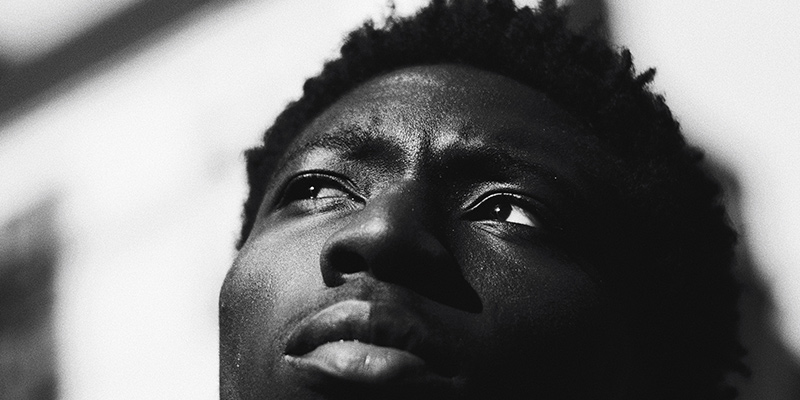

One of the ways that disposability is made most clear are police killings. In August, there was one week when police gunned down seven uncharged, unconvicted young men. But, while criminal suspects in other parts of the city are arrested and jailed, police kills the “disposable” young men of the ghetto because society, in its complicit silence, has agreed that it is more efficient this way.

We know that Kenyan civil society has long spoken up against police killings. The recent murders of Benson Njiru Ndwiga and Emmanuel Mutura Ndwiga while in police custody in Embu have rightfully incited public outrage. But what about the seven young men who were shot dead by police in Mathare within that one bloody week in August?

*****

On 9 August, 2021, a young man called Ian Motiso sat down to take a late lunch at a kibanda in Mlango Kubwa, Mathare when a killer cop called Blacky passed by. Blacky took out his gun and shot Motiso down then and there. Just like that, Motiso is no longer with us. He was 21 years old.

Another extrajudicial execution. Another life cut short.

Even though police killings continue throughout Kenya, people are speaking up about it now more than ever. A couple weeks ago, the Ndwiga brothers were detained in Embu by police. While in police custody, police beat them to death. The public responded with anger. National news covered it widely. Lawyers have taken up the brothers’ cases.

But what about Motiso? What about the other six young men killed in Mathare within that week? Almost silence.

People say that the young men police kill in the ghetto are “thugs.” People say that those who speak out against police killings simply do not understand what it is like to be a victim of crime in informal settlements. I was born and raised in Mathare. I have been a victim of crime. I know the pain of being robbed of valuable property. I know the pain of beatings from heartless young men. I know the pain of losing loved ones to “boys” who stab with knives.

Motiso committed crimes. Motiso personally attacked me. And Motiso did not deserve to be extrajudicially executed. I believe this, even though I still have a wound behind my right ear from when he bashed my head.

Two months ago, Smater Zagadat and I had just arrived at the Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC) to lead rehearsals for the MSJC Kids Club as usual. MSJC Kids Club is an initiative that uses dance and community theatre to advocate for social justice. Smater and I are the coordinators. That afternoon, I was wearing a black T-shirt with the logo “Dance with Zagadat”—Smater’s brand—so Smater took our her phone to take a picture of it. Within seconds, three teenagers swooped in and snatched the phone. We ran after them down towards the river and managed to catch the guy who grabbed the phone. Some kids from MSJC Kids Club followed behind.

We grabbed the thief and dragged him back up to the office so he could return Smater’s phone. But, suddenly, a group of young men came out of nowhere and attacked me. I only remember feeling their punches coming from all directions. Their fingers were covered with heavy coated rings. My teeth almost came out. I could not see what was happening, but I could see blood coming out of my mouth. All of this happened in the early evening on Mau Mau Road, between the bridge that connects Kambi Safi Road to Kosovo Hospital Ward, a very busy area—yet no one came to my rescue, except for the MSJC kids who shouted and cursed the attackers.

I recognized one of the attackers. Even though he recognized me back, he didn’t stop beating me. He felt no shame attacking someone he knew. He was Motiso.

Let me take you back, because I want you to understand something important. Motiso was born and raised in Mathare. He knew all six wards of Mathare very well, from the elderly to children. By the time he was 16 years old, he was already a very talented dancer and was a part of the Billian Music Family (BMF), together with Smater herself. The community loved these dance groups, and in return, the groups inspired many kids in Mathare, including myself.

The first time I saw BMF’s Dance group, I was just out of primary school. The dancers were performing “Vigelegele” by Willy Paul along Mau Mau Road. That was the first time I heard the name Motiso. The kids, yelling above the booming speakers, cheered for him as he danced.

“Umecheki vile Motiso amedo hiyo Stingo?!”

“Atakua dancer mgori!”

He was just that good, and I guess that’s why he easily became famous.

Growing up in Mathare, we all start out with beautiful dreams. A dream of becoming a doctor, police, engineer, professor, pilot, and so many more. Teachers used to tell us these dreams will only become true if you work hard. Maybe that’s why Motiso worked so hard to achieve his dream—to be a dancer.

Maybe if he wasn’t born into a poor family, his hard work would have turned his dream true. But Motiso was born into a place that reeks of all sorts of human rights violations, of poverty, of ecological injustice. His dream was shut down because of the environment he was brought up in. So, did he give up? Yes, Motiso gave up.

Imagine the struggle he passed through. First, he was unemployed. Motiso, like many of us in Mathare, was trapped in a cycle of wage slavery. You wake up, go to job, get a salary, barely make food and rent, sleep, repeat until you die. But your work never turns into a dignified life. You’re just trapped.

Second, Motiso was in the danger zone of being a man in his twenties living in the ghetto. As young men in Mathare, when we reach this age, we automatically become an enemy of the state. The ghetto is a place where a child grows up innocent, then later on becomes a victim of predators who target, hunt, and prey on them.

So Motiso went ahead and jumped on a bad bandwagon. He left dancing and got involved in crime like petty theft. The reason why he chose crime over a path of straightness is simple: He needed to survive.

Some people criticize his decision, asking why he should commit crime when the government has offered plenty of job opportunities to the youth, like one program called Kazi Mtaani. But, if those people understood that Mutiso was a victim of structural violence created by the system that we are born into, they would understand that they are demanding a young man to make “good” decisions while he chokes inside a system that has never treated him as a human.

Mutiso did try to join Kazi Mtaani, actually. A few months ago in Mathare, a group of young men went to the administration to register for Kazi Mtaani. But they were surprised to find that, in order to participate, they would first have to bribe the Area Chief 1,000 KES ($10). How can you look a young unemployed man in the eye, when you know he has no job, and ask him for money? Maybe the thieves who snatched Smater’s phone wanted to sell it in order to bribe the Chief and get a job.

Motiso will always be remembered as a thief. He robbed many. Many are still crying because of what he did.

But remember—he was also a friend. He was a family member.

He never deserved to be born into a system that does not care for poor people.

He never deserved to live in a world that kept poor people powerless in order to exploit them and, when they did what they wanted to survive, killed them off.

He did not deserve to be killed by the people whom we expect to protect us.

He never deserved that.