This article is also available in audio format. Listen now, download, or subscribe to “The Elephant In The Room” through your favourite podcast app.

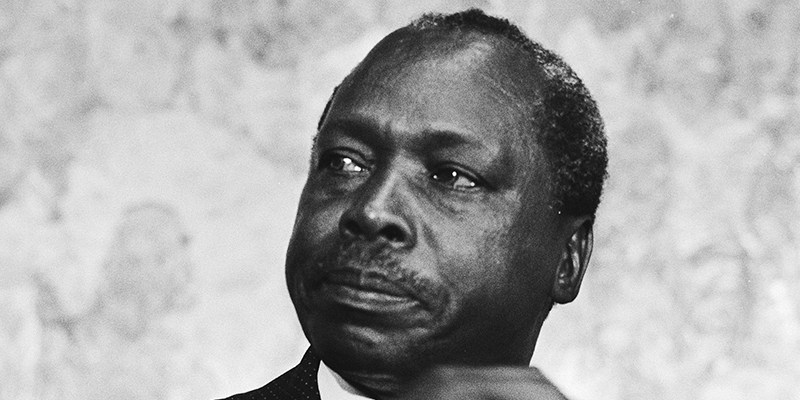

Nyayo! The word Nyayo conjures up the image of a past president and the experience of living under his regime. The term Nyayo had fallen out of usage for many of my peers until it was revived following the death of the former president of Kenya, Daniel arap Moi. I felt the power the word evoked before I knew its literal meaning. Nyayo means footsteps in Kiswahili. By the time Moi vacated power in 2002, I had become a proud member of a generation that believed in second chances and the eternal hope of a new spring. 18 years after Moi left power, his legacy still casts a long shadow. And so, for my generation, his death and memorial has created a moment for deep reflection.

I completed my 8-4-4 journey during Moi’s presidency. My first recollections of Moi are in primary school. This is the shared experience of a generation. I read with amusement several accounts of other Kenyans describing the anticipated presidential meet-and-greets, usually nothing more than a wave of the hand and a word of encouragement. From places as diverse as Turkana, Kitale and Nairobi, we shared the same stories. Each spoke of the reverence they accorded to a close encounter with the president. Many still speak of the Nyayo school milk programme with nostalgia. I remember the loyalty pledge and recall the words to the many songs composed in praise of Moi and his rule. These are the good memories we hang onto because the other memories of Moi’s rule are not pleasant.

After the failed coup attempt of August 1982, the sense of uncertainty grew as the regime’s aggression became more brazen. A normalisation of violence permeated society and the police operated like a predatory force. I remember the feeling of suppressed anger among the adults as life in Kenya became ngumu.

Moi was the nation’s father figure and therefore 24 years of Moi’s discharge of the role of fatherhood, both in the public and private spheres, was bound to have a tremendous influence on Kenyan patterns of masculinity. They say children ape what they see. Baba Moi was presented to us as the epitome of virtue yet what we experienced was the immorality of his power.

Baba wa Taifa, the fatherly figure I had grown accustomed to in primary school, had turned into an ogre in high school and by the time I joined university two decades later, he was a despot whose rule had become untenable.

The theme of fatherhood is a big part of Moi’s life journey. During his memorial service, his political protégés, President Uhuru, Deputy President William Ruto and opposition politician Musalia Mudavadi, all fondly remembered him as a father figure. Moi began his presidency in 1978 with a demand for blind loyalty and a public declaration that he would follow in the footsteps of the founding father of the nation, Jomo Kenyatta. Moi coined the Nyayo philosophy of peace, love and unity, which was no philosophical treatise at all but a command to comply unquestioningly. Moi took on his role with a zeal that in Mzee Kenyatta was never witnessed. He led from the front, touring the country building gabions and manifesting sporadic acts of generosity.

From the outset, Moi encouraged a culture of political sycophancy that thrived in the 80s. I became accustomed to seeing highly accomplished members of his cabinet heaping praises on Moi and pandering to his ego. No longer dazzled by the spectacle of majesty, I started becoming conscious of the contradictions of life under Nyayo and learning the place of fear in the patterns of duplicity I noticed in adult conversations. We rarely discussed politics at home or said anything negative in public about Nyayo because walls had ears. Witnessing those who suffered the consequences of engaging in anti-Moi politics drove us deeper into denial.

Moi the man, as many who met him have testified, was disarmingly charming. He was the head of a large family that he shielded from the spotlight. I knew of his famous sons—the late Jonathan, ace rally driver, and Gideon the polo player—as men of the world enjoying the perks of privilege. The other members of the family never, ever got any media coverage and were not easily recognisable.

The details of Moi’s marriage to Helena Bomet were never open to public scrutiny; better known as Lena, she was erased from public life and remained a mystery even after her death in 2004. (The grapevine did whisper, though, that the former president maintained a discreet bevy of mistresses.) We therefore readily accepted Moi as a bachelor by choice. A tall man who maintained good posture, dressed impeccably and exuded authority, Moi cultivated an ascetic persona and his robust form was attributed to a disciplined lifestyle that embraced a strong work ethic, eschewed alcohol and made sound nutritional choices. Moi also portrayed himself as a good Christian, scrupulously keeping up appearances of religiosity. He was the embodiment of the Jogoo (KANU’s party symbol), the dominant cockerel in the homestead, reinforcing his virility with a phallic symbol in the form of a rungu, a ceremonial club that became the subject of intense fascination among the youth.

I didn’t know anything about Moi’s own father or the stories of his childhood and how his upbringing influenced his adult life. That part of his life remained shrouded in mystery and in its place was the single story of an orphan boy from a humble background who, despite the adversity of the early years, was divinely destined for leadership.

Moi mirrored the stern father figure in the patriarchal tradition and Kenya was thus caricatured as a household with diverse personalities dominated by a harsh father who terrorised all into submission, a father who brooked no dissent and was consumed by anger. This is the male persona many of my generation experienced as the norm and Moi was just the extreme manifestation of a familiar parental figure. And so, while his methods were questionable, his motivation could be rationalised. He was the product of the prevailing cultural mindset.

Fathers start out as heroes to their children. The father epitomises the ideal a child aspires to become. It is the role of the father to bless the innocent child as he welcomes it into the world. A father who loses the capacity to bless becomes a curse to his children. So when a father turns abusive, the loss of trust overwhelms the psyche and pushes the child into a state of learned helplessness. A friend described being forced to watch as his father viciously caned the problem child of a large family as a more traumatising emotional experience than the actual physical punishment.

The overbearing personality of the father of the nation was familiar within many Kenyan households. But it is only after I became a father that I began to realise that a father’s bravado and outward show of strength is often a cover for vulnerability and in a culture where vulnerability is a sign of weakness, the façade is maintained even after the death of a patriarch.

Moi was not a relaxed man. He was rigid and vindictive. So when Mwai Kibaki came along with his unhurried manner and famed love of beer, the physical and emotional contrast between the two men was glaring. Kibaki came accompanied by a first lady, Lucy Kibaki, who had her own voice. The country witnessed the drama of a president’s private affairs playing out in public and a sense of vulnerability never previously seen from the holder of that high office. Kibaki was not pretending that he had it all together and he did not seem particularly bothered to be judged weak. Kibaki’s successor, Uhuru Kenyatta, has been humanised by the calm presence of his wife Margaret Kenyatta, despite the overriding sense of an irresponsible father completely divorced from the effects of his actions on those under his care. However, it remains apparent that Moi’s exaggerated masculinity has become the default position for political posturing. The Nyayo years birthed an alpha male complex that is still thriving and where politics is a charade of might, on display for the single purpose of retaining power, and that often involves violence.

It is difficult to mend a relationship with a father who uses violence to obtain validation. The refusal to forgive becomes an act of justice for those who have endured suffering. One can respect the context of the offender but forgiveness is much harder to arrive at without the active and honest participation of the offender. So many adopt a victim mentality, since we are socialised into a culture of violence that arose from the legacy of colonialism, and brutality is accepted as a rite of passage into adulthood.

The betrayal of a father figure and the shame the victim endures feeds an anger that can become self-consuming, leaving one feeling helpless. This is a national condition that has set in with the complete loss of trust in the ruling elite’s motivations, and is compounded by a sinking sense of entrapment because, even though Moi—personified as the original tormentor—is dead, his disciples still rule in the house that he built. It is the collective trauma of a generation communicating loudly in a silence that has been mistaken for solemnity. Death offers some exoneration, for it allows for courage to voice out one’s truth as an exercise in closure and as part of the process of forgiving a father shackled by his own notoriety.

In a society that retains rituals that build and preserve the community of the ruling elites, the citizens who are held hostage and turned against each other in the contest for power by the elites lose all hope of justice. After the conflict, the elites perform elaborate rituals of redemption and reconciliation while the citizens, torn by violence, are left with the bitterness of sharing space with their offenders. The leaders, guided by firm precedent, are never accountable for their excesses and those who have suffered under them learn to grieve in private.

The elaborate charade of Moi’s redemption ritual has been exhausting, knowing that those who share responsibility for the transgressions of the Moi regime continue to manufacture their own narratives of conversion. As justice is deferred, memory becomes the last space for contest but even that is no longer sacred.

To achieve closure for past atrocities and inhumanities and bring healing, one has to remember correctly. Though we are socialised to forget our pains through the doctrine of “accept and move on”, Sigmund Freud warned that we repeat what we don’t want to remember. Memory is necessary for healing for it aids in scrutinising the motives of the offender and the circumstances that gave birth to those motives so that we do not end up becoming what we hate. Psychologists talk of the limitation of focusing hate on a father when the problem lies beyond him. In understanding the circumstances that created the father, we gain a real chance to liberate ourselves from the bondage of our past.

We are a generation that seeks closure yet the death of a father figure only seems to have opened an old wound that we thought had healed. Therefore, we are called upon to engage in an honest introspection of the Nyayo era in order to understand what it takes to initiate the exercise of healing and reconciliation. Beyond the apportioning of guilt, the bigger task is to restore the broken social fabric that is devastating our communities. We need new rituals in the face of an impotent justice system, to get the offenders and the victims to share the bitter herb of truth lest we give over our whole lives to defending our positions and forgetting the value of restoring the disrupted social harmony in society. And it starts with acknowledging that Nyayo broke us and that our pieces were scattered to the four winds.