On Monday 15 August 2022, Kenya’s Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) Chairman, Wafula Chebukati, announced William Ruto of the Kenya Kwanza alliance as the country’s President Elect with 50.5 percent of the popular vote narrowly beating Raila Odinga of the Azimio la Umoja alliance with 48.8 percent.

As in 2013 and 2017 however, the fate of Kenya’s presidential election currently lies in the hands of the Supreme Court. This follows coordinated press statements by four Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) commissioners on 15 and 16 August, and by long-time opposition leader Raila Odinga on 16 August, and the submission of election petitions to the Supreme Court by Azimio and a group of Kenyan citizens on 22 August.

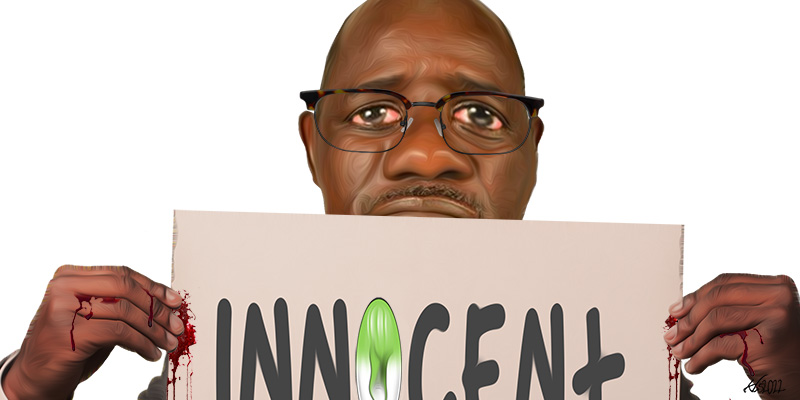

At the briefings on 15 and 16 August, the four commissioners stated that they could not “take ownership of the results” announced “because of the opaque nature which these results have been handled”, and because the total tally surpassed 100 per cent of the valid votes cast by 0.01 per cent even though the latter is likely due to a rounding error.

Odinga followed with a synchronised press briefing in which he argued that, because the “IEBC is structured as a democratic institution in which decisions must be taken either by consensus or by a vote of the majority . . . Chebukati’s announcement purporting to announce a winner is a nullity” and that his Azimio alliance would pursue “constitutional and lawful channels and processes to invalidate Mr Chebukati’s illegal and unconstitutional pronouncement”.

Azimio then added to these allegations in their election petition with claims that, among other things, some of the polling station-level forms (or forms 34A) were changed on the IEBC portal by hackers associated with Ruto; votes were added to the presidential vote in certain constituencies; the final results were declared without all forms 34A having been “received, uploaded and made publicly available for scrutiny”; Ruto failed to secure 50 per cent + 1 vote and so did not secure a first round victory; and the gubernatorial races in Kakamega and Mombasa were postponed with the “ulterior motive” of reducing turnout in Odinga strongholds.

It is yet to be seen whether or not the Supreme Court will view an announcement as a decision that requires consensus or a vote, and what detailed evidence Azimio will provide to support their claims of procedural problems and electoral malpractice, and how the court and Kenyans will respond.

What is clear however, is that, while Odinga and Azimio seemed to have an advantage going into the elections, the polls were incredibly close, with Ruto and Kenya Kwanza doing well at every level. Thus, while Ruto was announced president-elect with 233,211 votes more than Odinga, the Azimio petition claims that, when manual votes are included, Ruto actually secured 49.997 per cent of the popular vote. The upper and lower houses were also initially fairly evenly split. Thus, before a series of defections to Kenya Kwanza and before any electoral petitions, the Senate was initially composed of 33 Kenya Kwanza, 32 Azimio and 2 non-affiliated senators, and the National Assembly of 164 Azimio, 165 Kenya Kwanza, and 14 non-affiliated members of parliament (MPs) (with 6 seats yet to be declared) – while 21 governors were in Azimio, 22 in Kenya Kwanza, 2 independent, and 2 yet to be elected due to a mix-up with the gubernatorial ballot papers for Kakamega and Mombasa.

Odinga’s perceived advantage going into the polls stemmed from a number of factors. These included his track-record as an opposition leader of long-standing and support from the incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta. The latter translated into a sizeable war chest and the support of various state officials. The latter included chiefs in the national administration who, from my own research in Nyanza and the Rift Valley in the months prior to the elections, were found to be more proactive at mobilising voter turnout in Odinga than in Ruto strongholds, while many openly encouraged people to vote in line with the government. Odinga also enjoyed the support of a number of vocal civil society leaders, while some of the country’s main media houses were also widely perceived to be biased towards him. In this context, it was perhaps unsurprising that opinion polls ahead of the elections showed that Odinga had the momentum behind him, and was enjoying a marginal lead.

Nevertheless, the election remained too close to call in the weeks ahead of the polls. President Kenyatta’s support for Odinga – in the context of widespread dissatisfaction with the government’s performance especially around the all-important question of the economy – failed to sway many voters including in Kenyatta’s former stronghold of central Kenya where a majority rebelled against Kenyatta and voted for Ruto. Similarly, chiefs, who are state officials with increasingly minor duties, enjoy little capacity to direct the Kenyan voter.

Indeed, Kenyatta’s backing ended up being a poisoned chalice: it made Odinga appear to many as a “project”, rendered it difficult for Azimio to develop a clear campaign message that resonated with the majority of Kenyans, and encouraged a sense of complacency amongst many in the Azimio team. As a result, Odinga lost ground to Ruto and suffered from relatively low turnout in his former strongholds – most notably in Nyanza and at the Coast – and failed to make anticipated inroads into central Kenya.

On the other hand, Ruto and Kenya Kwanza undertook an impressive campaign. Ruto started early and traversed every part of the country. He also had a clear national message – he was a “hustler” who understood the problems facing the average Kenyan and would focus on a bottom-up process of economic reform that would bring capital and jobs – and ensured that he spoke to local issues wherever he went (somehow remembering the names of local leaders and places, and local development and socio-economic concerns, during his relentless tours). Ruto also emphasised his Christianity, made controversial donations to churches, and sought to distance himself from his association with violence during the post-election crisis of 2007/8 through (among other things) his religiosity, his backing of Kenyatta in 2013 and 2017, and focus on Kenyans’ economic troubles, and made much of his youth and energy, as compared to his older competitor.

Chiefs, who are state officials with increasingly minor duties, enjoy little capacity to direct the Kenyan voter.

Ruto also oversaw a more united alliance. Thus, while interviewees spoke of divides within Azimio – particularly between Odinga’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) and Kenyatta’s Jubilee Party (JP) – Ruto’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) remained dominant in Kenya Kwanza, and did a relatively good job at managing the party nominations.

As noted, we do not yet know what detailed evidence will be brought to court, whether the court will call for a fresh election, and whether Azimio would accept to go back to the polls with the current IEBC commissioners in place or call for a postponement and reforms. We also not do not know – if a fresh election were to be held – how such a competition would go. Much would depend on the evidence presented – and whether or not the general public comes to feel that the wrong person was announced the victor on 15 August – the resources that the two candidates have available, and turnout. The latter is particularly important. While the 9 August polls showed a relatively low turnout of 65 per cent, this would likely fall in any fresh election given that, as in previous elections under the 2010 Constitution, many Kenyans were likely not motivated to vote on 9 August by the presidential election, but by one of the other five elections held on the same day.

However, as things stand today, Ruto appears to be in a fairly strong position. Many Kenyans are tired of the elections and struggling economically and, if detailed evidence of electoral malpractice is not forthcoming, are likely to feel sympathetic towards the president-elect. Some who may have felt that Odinga was likely to win as the president’s favoured candidate, may feel more emboldened to vote for Ruto if the Supreme Court were to order a re-run. Finally, while Azimio and Kenya Kwanza have shared seats at various levels, it is Ruto’s UDA that has emerged from the elections as the strongest individual party with 24 senators and 17 governors as compared to ODM with 13 senators and 13 governors, which will likely help to facilitate a more intense grass-roots campaign for Ruto if a fresh presidential election does need to be held. Ruto’s position has been further strengthened by a movement of elected politicians towards Kenya Kwanza. This shift was spearheaded by 10 independent candidates who declared their backing of Kenya Kwanza on 17 August, followed by the United Democratic Movement (UDM), which moved from Azimio to Kenya Kwanza on 18 August taking with it 45 elected politicians including two governors, two senators, and 7 MPs.

As it stands, the country remains divided between supporters of Kenya Kwanza, supporters of Azimio, and those who believe that neither alliance will have much impact on their daily lives and who just want to make a living and support their families. Ultimately, it will be the latter group – and the numbers of them who can be persuaded to vote and for whom – that will determine any fresh election. Thus, while the official campaign period ended on 6 August, the informal campaigns and politics of persuasion will continue for some time to come.