In the weeks leading up to Kenya’s 2022 presidential election I wrote a piece that attempted to explain why Raila Odinga was not winning by a landslide and sent it in to the Elephant. It started by pointing out that given that Odinga was a long-term opposition leader who enjoyed strong support among the country’s marginalised and disenchanted communities, he might have expected to win the election at a canter after receiving the backing of President Uhuru Kenyatta. After all, the “handshake” between the two leaders appeared to have removed one of the main barriers to Odinga winning a general election, namely the state machinery that he and his supporters have consistently argued has been used to lock him out of power.

Yet despite the Azimio coalition bringing together the sitting president and the country’s most powerful opposition leader, Odinga did not seem to be running away with the election. The feeling I got from different parts of the country was that many voters were disenchanted with the handshake and the prospects of an Odinga/Kenyatta alliance. Opinion polls also suggested that the campaign was struggling to get into first gear, and that his main rival, William Ruto, retained an advantage. So I sat down to try and explain why, and wrote a piece about the four challenges that I thought his campaign faced, and why they meant he could lose the popular vote.

Then something changed.

The opinion polls began to shift. According to newspapers such as the Daily Nation, Odinga first went into a slight lead and then began to pull away. In one influential poll released just six days to polling day, the Daily Nation put Odinga 8 per cent ahead of Ruto. I distrusted these polls for a number of reasons: a nationally representative private poll my research group had commissioned put the election much closer, with Odinga leading by just over 2 per cent; telephone-based and computer-assisted polls would ignore the poorest members of society, who might be more likely to support Ruto’s “bottom up” economic message; some respondent’s may have been worried about saying they would vote for a candidate not favoured by the president; and, the media had tended to favour Odinga in its coverage. But as more and more polls came out giving Odinga a large lead, my belief in my argument waned. Maybe I had got it wrong, and the Azimio campaign had found a way of overcoming its own contradictions.

I soon lost confidence in my argument and, not wanting to publish analysis that I wasn’t sure about, I wrote to the editors at the Elephant asking them to shelve the piece.

In the wake of the announcement that William Ruto had won the presidential election with 50.49 per cent of the vote, my mind has consistently returned to the piece, because I think it may shed some light on the outcome. The results, of course, have been rejected by Odinga’s team which has petitioned the Supreme Court to try and overturn Ruto’s victory. But even if Kenya heads to a “fresh” election, or a run-off, it seems clear that Azimio struggled to excite and mobilise the electorate – including in his “home” counties. Whatever this was, it was not a resounding victory for Odinga and the “handshake”.

So in the hope that it might help those seeking to understand what happened in the elections – and because the analysis will still be relevant if the country requires a second presidential poll – I decided to publish the initial piece. The main analysis – which starts in the first section below – remains untouched. All that has been changed is this introduction, with a new conclusion inserted at the end of the piece to connect the discussion to the actual election results.

My argument ran as follows. Odinga’s campaign suffered from four major challenges: the fact that he lost popular trust following the handshake with Kenyatta, the president’s own unpopularity among key communities and his inability to deliver his own community, the mixed messages being sent out by the campaign, and a complacency that the election was in the bag. These weaknesses threatened to undermine his support not only in competitive areas such as central Kenya, but also in his own heartlands. This might not have mattered against a weak opponent, but Odinga was facing one of the most effective strategists in Kenyan politics. Ruto had begun to lay the groundwork for the 2022 campaign well in advance of 2017, ensuring that his allies were elected in key areas in that year’s general elections. In addition, through his “hustler” narrative and critique of privileged “dynasties” Ruto had hit upon a message that resonated with a cross-section of Kenyans suffering significant economic hardships.

If Odinga’s campaign did not resolve its internal contradictions, I argued, Ruto could well emerge victorious.

From this point onwards, I reproduce original article.

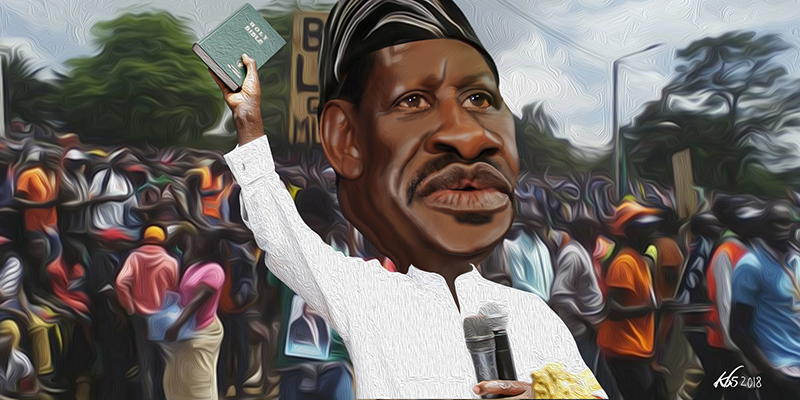

No longer the people’s president

Odinga’s reputation as an opposition stalwart was hard won and well deserved. He played a key role in helping Mwai Kibaki to mobilise support ahead of the 2002 elections, securing the country’s first ever transfer of power at the ballot box. Odinga then broke from President Kibaki when it became clear that he had no intention of either pursuing constitutional reform or keeping the promises he had made to his allies. Having defeated Kibaki in a constitutional referendum that would have taken the country backwards, he continued to campaign for reform.

Ruto had begun to lay the groundwork for the 2022 campaign well in advance of 2017, ensuring that his allies were elected in key areas in that year’s general elections.

In this way, Odinga played a major role in the introduction of a new constitution in 2010, even if it took the 2007/8 post-election crisis to generate the necessary political will to change the rules of Kenya’s political game. With the introduction of a Supreme Court and a system of devolution that created 47 new county governments, this represented a major democratic breakthrough that has profoundly shaped the country’s politics ever since.

Despite serving as Prime Minister in the power sharing administration that ushered in the new constitution, Odinga’s reputation as an opposition leader was further cemented in the years that followed. On the one hand, he was declared the loser in a series of close and often bruising election defeats in 2007, 2013 and 2017, which were made even harder to take by the fact that each time he was convinced he had been cheated. On the other hand, Odinga increasingly refused to play politics by the rules laid down by President Kenyatta, boycotting the “fresh” presidential election in 2017 and then refusing to accept the legitimacy of Kenyatta’s victory – ultimately being sworn in as the “people’s president” by his supporters in a controversial ceremony in Nairobi.

Against this backdrop, the “handshake” between Odinga and Kenyatta that ended their long-running standoff on 9 March 2018 took many of his supporters by surprise. Moving into government, and securing no immediate concessions in return for calling off his protests, made it look like Odinga had given up his fight for political change. Worse still, it opened him up to accusations that he had sold out those who had made great sacrifices to fight his corner, prioritising his own wealth and security ahead of their dreams.

The impact of this move on Odinga’s reputation continues to be underestimated, even today. At the elite level, it led to figures such as public intellectual and political strategist David Ndii abandoning Odinga and throwing their weight behind Ruto on the basis that he represented the only credible challenge to the corrupt ruling clique. But perhaps the biggest impact was among ordinary Kenyans. In a nationally representative survey conducted in mid-July 2020, only 18 per cent of respondents said that they trusted Odinga “a lot” and 42 per cent said “not at all”. This decline was not only felt among groups that have historically not associated with Odinga such as those who live in central (51 per cent “not at all”), it also extended to western (45 per cent) and even Nyanza itself (31 per cent).

Controversial primaries or “nominations” don’t help this situation. As I wrote at the time, discussing the winners and losers of the process, “Odinga—and his ODM party—have come out rather bruised. They have been accused of nepotism, bribery and of ignoring local wishes. This is a particularly dangerous accusation for Odinga, as it plays into popular concerns that, following his “handshake” with President Kenyatta and his adoption as the candidate of the “establishment”, he is a “project” of wealthy and powerful individuals who wish to retain power through the backdoor after Kenyatta stands down having served two-terms in office.”

What is particularly striking about the trust numbers from July 2020 is that at the time the poll was conducted – the numbers shifted in later surveys – trust in Odinga lagged considerably behind William Ruto. According to the poll, only 23 per cent of Kenyans trusted Ruto “not at all” and this figure was particularly low in key battleground regions such as central (19 per cent). This represented a remarkable turnaround for Ruto – who was once found by a survey to be the most feared leader in Kenya – and meant that Odinga started the 2022 election campaign from a position of weakness.

The Kenyatta problem

The reputational fallout from the handshake has been reinforced by the strong support Odinga’s candidacy has received from President Kenyatta and his allies. Not only is the president visibly in Odinga’s corner, but his allies in the ruling party are active parts of the Azimio coalition. This has created the perception that Odinga is being used as a stooge by the Kenyatta family and their clique to protect their interests in the next government.

Such an accusation would not have been so damaging in the past, but Kenyatta’s credibility has fallen in the last five years. Against the backdrop of a struggling economy and rising unemployment and poverty during the COVID-19 pandemic, the president’s failure to deliver on key election promises, or to reduce corruption, has created the perception that he and his government are part of the problem rather than part of the solution. This situation is only likely to get worse over the coming months, as the fallout from the war in Ukraine and the food shortages in the region push up the prices of essentials. Petrol prices are already set to be the highest in Kenyan history.

The reputational fallout from the handshake has been reinforced by the strong support Odinga’s candidacy has received from President Kenyatta and his allies.

Odinga’s dependence on Kenyatta for financial and state support is thus as much of a curse as it is a blessing. At a moment when many Kenyans are desperate for change, Odinga’s alliance with Kenyatta makes him look like the continuity candidate.

Yet this is not the worst of it. Being seen to be a “project” or a “puppet” for other interests can be politically fatal in Kenya because it implies that a leader cannot be trusted to deliver to their own communities. Odinga should know this well, because it was in part this accusation that undermined the efforts of Musalia Mudavadi to mobilise the support of his Luhya community in the 2013 general election, and so enabled Odinga to dominate the vote in western province. Mudavadi’s career has never fully recovered.

Odinga may also gain little from Kenyatta’s support in central Kenya itself. At present he is losing the region in most credible opinion polls despite Kenyatta’s support, and it is unclear whether Kikuyu leaders can really rally support for a leader who they have demonised repeatedly for decades. Kenyatta is also highly unpopular in parts of central Kenya himself – in a survey our research team conducted in July 2022, 21 per cent of Kikuyu, Embu and Meru voters said that Kenyatta’s endorsement made them less likely to vote for a candidate, compared to 17 per cent of Luos.

Yet despite this, Azimio has done little to counter the idea that Odinga is not his own man. Instead of creating clear blue water between the two leaders when setting up the new coalition, Azimio appointed Kenyatta as its chairman. And by using Kenyatta’s speeches as a vehicle to demonise Ruto and so try and so limit his support in central Kenya, Azimio has consistently reminded Kenyans that Kenyatta is a central part of the Odinga team. This created a gaping open goal, enabling Odinga’s opponents to score numerous points at his expense. Most notably, Ruto – always one to find a punchy phrase to sum up popular frustrations – has taken great delight in warning that if Odinga were to win, Kenyans would suffer a “remote-controlled presidency”.

Mixed messages

In the past, Odinga’s messaging was powerful and clear, but it is now unconvincing. This is partly because his campaign has to cope with the internal contradictions of being an opposition leader backed by the establishment. But it also reflects muddled thinking and a failure to capture the public imagination.

Back in the day, you knew where you were with an Odinga campaign. He was in favour of constitutional reform, devolution, and shifting power and resources in the direction of the country’s economically and politically marginalised ethnic groups. This gave him a clear brand and an obvious set of slogans. Things have looked rather different since 2010, however, and it is important to realise that the challenges facing Odinga have a history that predates the 2022 general elections.

Being seen to be a “project” or a “puppet” for other interests can be politically fatal in Kenya because it implies that a leader cannot be trusted to deliver to their own communities.

In one respect, Odinga was a victim of his own success. The achievement of a new constitution complete with devolution took away one of his main demands. Thereafter, Odinga’s team has struggled to find as effective a framing device that would resonate with as wide a range of communities. In post-2010 elections, Odinga has presented himself as the defender of the new arrangements – the only leader who could be trusted to make sure that devolution was protected and extended. In some ways this made sense – devolution was very popular – but as all good politicians know, promising to make something a bit better is never going to excite voters as much as promising something completely new and game changing.

Campaigning on the same issue also risked making Odinga look like a one trick pony – something that his then Jubilee rivals took full advantage of. In 2013, for example, Jubilee leaders sought to tap into popular excitement at the new technological opportunities transforming the country by claiming that they were “digital” while Odinga was “analogue”.

The 2022 campaign has brought with it even greater challenges. By presenting himself as the opposition candidate on the side of Kenya’s hard working “hustlers”, Ruto has appropriated Odinga’s approach and updated it for a new generation. At the same time, the closer relationship between Odinga and Kenyatta has generated suspicions that an Azimio government would predominantly benefit their Kikuyu and Luo communities, respectively. The obvious implication of this is that an Odinga presidency would preserve rather than challenge the greater economic and political opportunities that communities that have held the presidency currently enjoy. Along with Odinga’s damaged reputation, this has made it much harder to craft a message that resonates with communities that have never tasted power – i.e. with Odinga’s historical support base.

These issues have led Odinga to make a series of speeches that have been couched in warm tones, identifying important lessons from Kenya’s past without presenting any clear blueprint for how to navigate its future. Such narratives no doubt evoke warm memories, in particular the role that Oginga Odinga and Jomo Kenyatta – Raila and Uhuru’s fathers – played in the nationalist struggle. But they are unlikely to excite the county’s youth, who are too young remember this history, have borne the brunt of recent economic downturn, and represent more than three-quarters of the population.

These challenges could have been overcome by a creative campaign that highlighted past government failings and promised to put them right. But Azimio has gotten itself in such a mess that such a campaign has not been possible. There are two aspects to this. First, it is unclear who is actually in control of Odinga’s campaign. Strong rumours suggest that powerful figures around Kenyatta – most notably his influential brother Muhoho – have as much sway as long-time ODM leaders. It is not hard to see how such a situation would lead to mixed messages and undermine Odinga’s ability to position himself against Kenyatta’s legacy. While the president is understood to have informed Odinga’s team that he understands that they may need to distance his candidacy from the current government, others around Kenyatta are said to be extremely sensitive about any criticism, binding the hands of Odinga’s speech writers.

As all good politicians know, promising to make something a bit better is never going to excite voters as much as promising something completely new and game changing.

Second, the Azimio coalition has struggled for unity and purpose. The difficulty of integrating its numerous parties into a common organization and slate of candidates was so great that it proved to be easier to change the law to allow coalitions to be registered as parties than to create a more unified political vehicle. Ruto’s Kenya Kwanza alliance is not without these challenges, but the greater number of leaders and parties involved on the Azimio side mitigates against a clear and coherent structure and leadership. As Pamoja African Alliance (PAA) spokesperson Lucas Maitha put it, as his party tried to quit the coalition: “There is a lot of confusion in the coalition today. Nobody knows who is calling the shots in Azimio”.

The lack of integration within the coalition also means that it risks fighting against itself when it comes to some downstream races for Governor, Senator, Member of Parliament and MCA. Kenyans don’t have to look back far in history to see the impact that this kind of fragmented campaign can have. It was exactly the same set of challenges that undermined the campaign of President Kibaki’s Party of National Unity in 2007, and led to what was effectively the “incumbent” grouping losing control of the National Assembly.

The complacency of the powerful

You might have thought that the challenges outlined above would lead to significant changes to the campaign structure and a real sense of urgency. Instead, what is striking is the apparent complacency within the Azimio coalition. This appears to be rooted in two assumptions. The first is that Kenyan politics is still essentially an ethnic census, in which success simply requires you to recruit the most “Big Men” (or “Big Women”). The second is that whichever candidate has the backing of the state is bound to win. On that basis, Odinga cannot lose.

But these are flawed and deeply dangerous assumptions. Many of the leaders behind Odinga have no capacity to direct the votes of the communities they claim to lead. Odinga gained ground on Ruto when other leaders such as Kalonzo Musyoka officially joined his side, but the likes of Gideon Moi and Charity Ngilu bring few votes with them. Ruto has also demonstrated a remarkable ability to penetrate the support base of his rivals, and is currently the most popular candidate among the Kikuyu, turning assumptions about ethnic voting on their head.

The assumption that the state can simply deliver an election is also problematic. Spending more money doesn’t mean you necessarily get more votes – especially if the money is seen to be tainted by corruption. Using the security forces to intimidate rival voters or applying pressure to the electoral commission can be effective, but if Odinga remains behind in the polls, any blatant attempt to manipulate the process would return Kenya to the political crisis of 2007/8. Moreover, with the emergence of an assertive Supreme Court that just rejected Odinga’s proposed “Building Bridges Initiative” constitutional changes, even these more cynical strategies can no longer guarantee victory.

Spending more money doesn’t mean you necessarily get more votes – especially if the money is seen to be tainted by corruption.

Azimio leaders therefore have no room for complacency. Yet that is just what they are demonstrating.

The original text ends here; what follows is a reflection on the official results of the election, and what they tell us about the accuracy of the foregoing arguments.

The 2022 election results: The Handshake blues

It is too early to know what the 2022 election results will look like after a Supreme Court petition, and correlation is not causation, but some of the results suggest that the intuitions outlined above may have been on the money.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the results was the strength of support for Ruto in Central Kenya. Most notably, neither Kenyatta nor Odinga’s running mate Martha Karua proved able to mobilise much support in the region. While Odinga performed better than he had done in 2017 – demonstrating that he did gain something from his chosen alliances – Ruto convincingly defeated him in Kenyatta and Karua’s home polling stations. In Murang’a County, Ruto secured over 343,000 and Odinga just over 73,000, with a turnout of 68 per cent. In Nyeri, Ruto won with 272,000 votes and Odinga just 52,000, on another 68 per cent turnout. And in Kiambu Ruto polled a massive 606,000 to Odinga’s 210,000 on a 65 per cent turnout.

Much less commentary has focussed on the elections in what are usually thought of as Odinga’s home areas, in part because much of the Azimio accusations of electoral manipulation have focussed on central Kenya, but there is an interesting story to be told here as well.

Things don’t look that damaging for Odinga if you just scan the numbers quickly without putting them in context. In Homa Bay, Odinga polled almost 400,000 votes and Ruto got under 4,000 on a 74 per cent turnout. Odinga also won overwhelmingly in Siaya (371,000 to 4,000) on a 71 per cent turnout and in Kisumu (420,000 to 10,000) on a 71 per cent turnout. These landslide victories are the stuff of politicians’ dreams, and turnout percentages in the 70s look healthy compared to most parts of the world.

Indeed, these results look pretty good until you remember that these counties are in Odinga’s electoral base, where he was hoping for the kind of overwhelming wall of support he received in previous elections. In 2013, turnout in Nyanza was 89 per cent. Homa Bay recorded 94 per cent, Siaya, 92 per cent, Kisumu 90 per cent – an average of around 20 per cent higher than 2022. Moreover, comparing the 2022 turnout in these areas with Ruto’s heartlands reveals striking differences. In Bomet, Ruto won 283,000 votes to Odinga’s 13,000 on a turnout of 80 per cent. In Elgeyo Marakwet, he secured 160,000 to Odinga’s 5,000 on a 78 per cent turnout. And in Kericho he polled 319,000 to Odinga’s 15,000 on a turnout of 79 per cent. Overall, the four counties in the country with the highest turnout all went to Ruto.

Odinga also suffered from a similar drop in turnout in other areas that have historically supported him. While he won the vote at the Coast, in a number of counties it was much closer and turnout collapsed. In Mombasa, Odinga polled 161,000 votes to Ruto’s 113,000 on a turnout of just 44 per cent. Azimio leaders will complain that this was due to the last minute cancellation of the governorship election, and that that may have had an impact, but Mombasa was far from the only county in the Coast to see a decline. In Kwale, it was 125,000 for Odinga and 52,000 for Ruto on a 55 per cent turnout. Back in 2013, turnout had been 66 per cent in Mombasa and 72 per cent in Kwale. While turnout declined in every county in 2022, the route to victory planned by the Odinga team assumed that they would be able to at least match his 2017 performance in his home areas now that he was backed by the power of the state.

Taken together, these figures suggest a common story. Potential Azimio voters in all three regions were unpersuaded by the handshake. In central Kenya, former Kenyatta supporters were not prepared to accept Odinga and instead flocked to Ruto. In Nyanza and the Coast, some Odinga supporters, disenchanted by his alliance with Kenyatta stayed at home, denying him the numbers needed for victory. Had Nyanza and the Coast turned out as they have done in the past, Odinga would not just have secured a second round run-off, he would probably have won outright.

Odinga also suffered from a similar drop in turnout in other areas that have historically supported him.

This is not to imply that Ruto did not earn his victory – he campaigned hard on a message cleverly designed to profit from Odinga’s difficulties, and many of the votes he won were not simply negative rejections of the handshake but a vote for change. But that message was so effective against Odinga – the archetypal “change” candidate – precisely because the handshake and his alliance with Kenyatta undermined his ability to persuade potential supporters that his presidency would deliver anything different to the last eight years.

This core challenge will remain if the presidential election needs to be re-run, and even now it seems like key lessons are not being learned. With so much effort going into making allegations of electoral manipulation, there seems to have been little time for Azimio leaders to reflect on what may have gone wrong and why. Even if those around Odinga believe they were hard done by in Central, it doesn’t seem plausible that their performance was undermined by manipulation in Nyanza, an area in which Ruto’s team has had very little presence. Yet there seems to be little recognition that Azimio may have simply have gotten its tactics badly wrong.

If the campaign strategy remains the same, with the added challenge of having to re-mobilise citizens who are tired of the election and may blame Azimio for further disruption on the basis that they refused to accept defeat, the outcome of a “fresh” election is unlikely to be different to the first.