In the previous article we discussed the Kenyan Supreme Court’s BBI judgment, on the issue of basic structure and limitations upon the constitutional amending power. That discussion provides an ideal segue into the second major issue before the Court: the interpretation of Article 257 of the Kenyan Constitution, which provides for constitutional change through the “popular initiative”.

Recall that other than the substantive challenge to the contents of the BBI Bill, another ground of challenge was that, on a perusal of the record, the president was the driving force behind the Bill (the High Court called him the “initiator”), going back to the time that he engaged in a “handshake” with Raila Odinga, his primary political rival at the time. It was argued that Article 257’s “popular initiative route” was not meant for state actors to use – and definitely not for the head of the executive to use. It was meant to be used by ordinary people, as a method for bringing them into the conversation about constitutional reform and change. The High Court and the Court of Appeal (see here) agreed with this argument; the Supreme Court did so as well, although it split on the question of whether the president had, actually, been impermissibly involved with the popular initiative in this case.

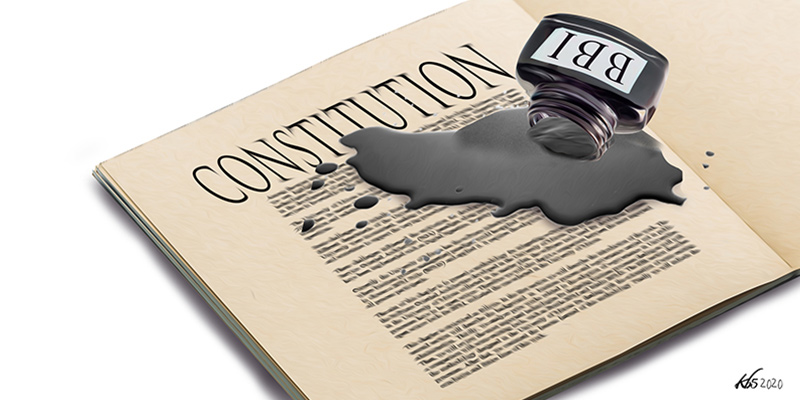

The Long Shadow of the Imperial Presidency

At the outset, it is important to note that Article 257 does not explicitly bar the president from being a promoter (the technical term) or an “initiator” of a popular initiative (Ibrahim J, paragraph 784). Any restriction upon the President, in this regard, would therefore have to flow from an interpretation of the constitutional silences in Article 257.

How does the Supreme Court fill the silence? As with its analysis of the basic structure, the Court turns to history. Where the point of Chapter XVI was to provide internal safeguards against hyper-amendments, more specifically, Article 257 – as gleaned from the founding documents – came about as a response to the “Imperial Presidency”, i.e., the period of time under Kenya’s Independence Constitution, where power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the president, and where the president was in the habit of simply amending the Constitution in order to remove impediments to the manner in which he wished to rule (Koome CJ, paragraph 243; Mwilu DCJ, paragraphs 463, 472; Wanjala J, paragraph 1046; Ouko J, paragraph 1917-1918).

This being the case, the Supreme Court holds, it would defeat the purpose of the popular initiative to let the president back in. The purpose of Article 257, according to the Court, is to provide an avenue for constitutional change to the People, as distinct from state organs (Mwilu DCJ, paragraph 491; Ibrahim J, paragraph 789; Lenaola J, paragraph 1537). In other words, the scheme of Chapter XVI – with its twin parliamentary (Article 256) and popular initiative (Article 257) routes – is to balance representative and direct democracy when it comes to constitutional change (Koome CJ, paragraphs 237 – 242; Mwilu DCJ, paragraph 480; Wanjala J, paragraph 1042; Lenaola J, paragraph 1535; Ouko J, paragraph 1900). That balance would be wrecked if Article 257 was to be converted from a bottoms-up procedure for constitutional change to a top-down procedure, driven by the president.

This is a particularly important finding, whose implications extend beyond the immediate case. Recall that the contest over the interpretation of Article 257 was – as so much else in this case – a contest over legal and constitutional history. While the challengers to the BBI Bill told the story of the imperial presidency, its defenders told a different story entirely: for them, Article 257 was not about constraining the president, but about enabling them. The situation that Article 257 envisaged was one where a recalcitrant parliament was stymying the president’s reform agenda; in such a situation, Article 257 allowed the president to bypass parliament, and take their proposals directly to the people.

The contest, thus, was fundamentally about the relationship between power, presidentialism, and the 2010 Constitution. Was the 2010 Constitution about constraining the imperial presidency – or was it about further entrenching the power of the president vis-a-vis other representative organs? And thus, in answering the question the way it did, the Supreme Court not only settled the fact that the president could not initiate a popular initiative, but also laid out an interpretive roadmap for the future: constitutional silences and ambiguities would therefore be required to be interpreted against the President – and in favour of checks or constraints upon their power – rather than enabling their power. This is summed up in paragraph 243 of Koome CJ’s opinion, which demonstrates the reach of the reasoning beyond its immediate context:

In its architecture and design, the Constitution strives to provide explicit powers to the institution of the presidency and at the same time limit the exercise of that power. This approach of explicit and limited powers can be understood in light of the legacy of domination of the constitutional system by imperial Presidents in the pre-2010 dispensation. As a result, Chapter Nine of the Constitution lays out in great detail the powers and authority of the President and how such power is to be exercised. In light of the concerns over the concentration of powers in an imperial President that animate the Constitution, I find that implying and extending the reach of the powers of the President where they are not explicitly granted would be contrary to the overall tenor and ideology of the Constitution and its purposes. (Emphasis supplied)

Furthermore, in this context, Koome CJ’s endorsement of Tuiyott J’s opinion in the Court of Appeal (Koome CJ, paragraph 256) becomes particularly important. As Tuiyott J had noted, simply stating that the president is not allowed to initiate a popular initiative will not solve the issue; there are many ways to do an end-run around such proscriptions – for example, by putting up proxies (as arguably did happen in this case). What is thus required is close judicial scrutiny, and the need for a factual analysis that goes behind a proposed popular initiative, in order to ensure that it is genuinely citizen-driven, and not a front for state actors (especially the president) (see also Mwilu J, paragraph 509, for some of the indicators, which she suggests ought to be addressed legislatively). Indeed, a somewhat more formal reading of the process (with respect) led to Lenaola J dissenting on this point, and finding that the president was not involved, as it was not he who had gone around gathering the one million signatures for the popular initiative. Thus, how well the judiciary can police the bounds of Article 257 is something only time will tell; in the judgments of the High Court, Court of Appeal, and now the Supreme Court, the legal standards – at least – are in place.

Public Participation

The Supreme Court unanimously found that the Second Schedule to the BBI Bill – which sought to re-apportion constituencies – was unconstitutional. Their reasons for doing so differed: a majority holds that there was no public participation; Mwilu J also holds that the amendment was not in harmony with the rest of the Constitution (paragraph 533) and Wanjala J says that it amounted to constitutional “subversion” (paragraph 1063), on the basis that it amounted to a direct takeover of the functioning of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission – raising some of the basic structure issues discussed in the previous post. On public participation with respect to the rest of the BBI Bill, the Court split 4 – 3, with a wafer-thin majority holding that – on facts – there had been adequate public participation in the process thus far. In this context, it is important to note that CJ Koome – one of the majority of four – notes elsewhere that the most intense public participation – that is, voter education, etc. – occurs at the time of the referendum (which had not yet happened in the present case).

Was the 2010 Constitution about constraining the imperial presidency – or was it about further entrenching the power of the president vis-a-vis other representative organs?

A couple of other points arise for consideration on the point of public participation. The first is that in a dispute about whether or not there was adequate public participation, who bears the burden of proof? On my reading, a majority of the Court holds that it is the state organs which bear the burden of demonstrating that there was adequate public participation (Koome CJ, paragraph 270, 311; Mwilu J, paragraphs 599, 604; Ibrahim J, paragraph 849; Wanjala J, paragraphs 1096 – 1097). The rationale for this is set out by Ibrahim J at paragraph 849:

With profound respect, as stated by Musinga, (P), the amendment of a country’s constitution, more so our Constitution, should be a sacrosanct public undertaking and its processes must be undertaken very transparently and in strict compliance with the country’s law.

This chimes in with the Court’s finding that the tiered amendment process under Articles 255 – 257 is an internal safeguard against abusive amendment. Needless to say, if that interpretation is indeed correct, then within the scheme of Articles 255 – 257, constitutional silences should be interpreted in a manner that protects the citizenry from abusive amendments; one of the most important safeguards is public participation, and it therefore stands to reason that the burden of establishing it – especially where state organs are concerned within the scheme of Article 257 – should be on the state. In this context, it is interesting that other than repeatedly emphasising that Article 257 was an onerous, multi-step procedure whose very onerousness was designed to protect the basic features of the Constitution, Koome CJ is the only judge to both hold that the burden lay upon State organs, and to hold that the burden was discharged in this case.

The second point about public participation is the Court’s finding that it flows throughout the scheme of Article 257, with its specific character depending upon what stage the amendment process was at: at the promoters’ stage, at the stage of the county assemblies, at the stage of the legislature, and at the stage of the referendum. A majority holds – and I think correctly – that at the initial stage – the promoters’ stage – the burden is somewhat, especially given that this is the only stage where state institutions are not involved, and the burden falls upon the promoters, who are meant to be ordinary citizens.

Given the contested facts in this case – which are discussed at some length in the separate opinions – it will be interesting to see how future judgments deal with the issue of public participation under Article 257, especially given the Court’s finding that it is this tiered amendment process that is meant to protect against abusive amendments.

The Quorum of the IEBC

Recall that a key question before the High Court and the Court of Appeal was whether the IEBC, working with three commissioners, had adequate quorum, notwithstanding the fact that the Schedule to the IEBC Act fixed the quorum at five. The High Court and the Court of Appeal held that it did not have quorum; the Supreme Court overturned this finding.

The reasoning of the judges on this point overlaps, and can be summed up as follows: Article 250(1) of the 2010 Constitution states that “each commission shall consist of at least three, but not more than nine, members.” This means that, constitutionally, a commission is properly constituted with three members. Any legislation to the contrary, therefore, must be interpreted to be “constitution-conforming” (in Koome CJ’s words), and read down accordingly (Koome CJ, paragraph 325 – 326, 336 – 337; Mwilu J, paragraph 661; Wanjala J, paragraph 1113; Ouko J, paragraphs 2060, 2070).

How well the judiciary can police the bounds of Article 257 is something only time will tell.

With the greatest of respect, textually, this is not entirely convincing. If I say to you that “you may have at least three but not more than nine mangoes”, I am leaving the decision of how many mangoes you want to have up to you; I am only setting a lower and an upper bound, but the space for decision within that bound is entirely yours. Similarly, what Article 250(1) does is set a lower and upper bound for Commissions and quorum, with the decision of where to operate in that space being left up to legislation (see Ibrahim J, paragraph 892). This point is buttressed by the fact that under the Transitional Provisions of the Constitution, it is stated that

“Until the legislation anticipated in Article 250 is in force the persons appointed as members or as chairperson of the Salaries and Remuneration Commission shall be appointed by the President, subject to the National Accord and Reconciliation Act, and after consultation with the Prime Minister and with the approval of the National Assembly.”

I would suggest that this indicates that the appropriate body for implementing Article 250 is the legislature, and consequently, questions about quorum and strength ought to be left to the legislature (subject to general principles of constitutional statutes and non-retrogression, discussed here).

Conclusion

There were, of course, other issues in the judgment that I have not been dealt with here; the question of presidential immunity, for example. In this article, however, we have seen that the overarching finding of the Court – that the tiered amendment procedure under Articles 255 – 257 is meant to provide an internal safeguard against abusive constitutional amendments and hyper-amendments – necessarily informed its interpretation of Article 257 itself, in particular, in holding that the president cannot initiate a popular initiative, that the burden of demonstrating public participation lies upon the state, and that public participation is a continuing process flowing through the several steps of Article 257. In the final – and concluding – article, we shall examine some of the other implications of this logic, in particular upon issues such as distinct and separate referendum questions.