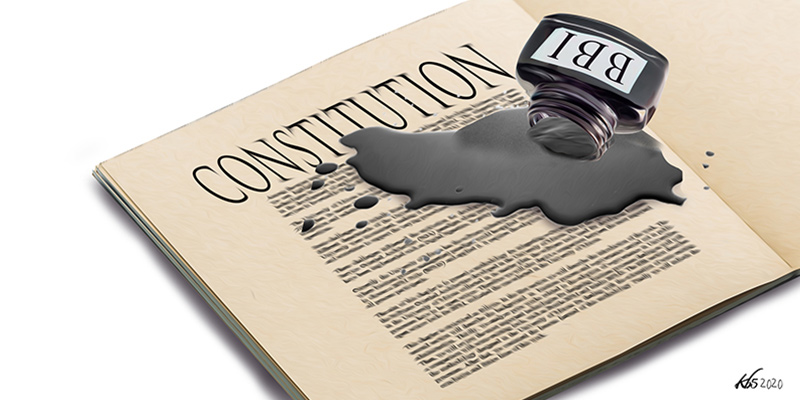

On 5th April 2022, a seven-judge bench of the Kenyan Supreme Court delivered judgment in The Hon. Attorney General and Ors v David Ndii and Ors [“the BBI Appeal”]. The judgment marked the judicial culmination of the constitutional challenge to the BBI Bill, which had proposed seventy-four amendments to the 2010 Constitution of Kenya. Recall that the case came up in appeal from the judgments of – first – the High Court of Kenya, and then the Kenyan Court of Appeal, both of which had found the Bill unconstitutional for a variety of reasons. The Supreme Court, thus, was the third Court to hear and decide the issue; and over a period of one year, as many as nineteen judges heard and decided this case. The Supreme Court framed seven issues for judgment, which can be found in Martha Koome CJ’s lead judgment and the seven judges wrote individual opinions.

In the course of three articles, I propose to analyse the judgments in the following manner. In this first article, I will consider the issue of the basic structure. In the second article, I will consider the issue of the popular initiative to amend the Kenyan Constitution under Article 257, and some of the remaining points in the judgment(s). In the final article, I will examine some of the potential implications of the judgment(s) going forward (for example, on the issue of whether referendum questions for constitutional amendment must be distinct and separate). It is safe to say that, as with the judgments of the two other superior courts, the range and novelty of the issues before the Court mean that its verdict will be studied across the world for a long time to come.

On the Basic Structure: An Introduction

Recall that the High Court and the Court of Appeal had both held that the basic structure doctrine was applicable in Kenya. In addition, both Courts had also held that in concrete terms, this meant that any alteration to the basic structure of the Kenyan Constitution could take place only through an exercise of the People’s primary constituent power, which existed outside of the Constitution. The primary constituent power was essentially the power to make or remake a Constitution, and could therefore only be done under the framework within which the 2010 Constitution had originally been drafted. This – according to both Courts – required a four-step sequential process: civic education, public participation, a Constituent Assembly, and a referendum. The correctness of these findings was at issue before the Supreme Court.

The formal disposition of the Court indicates that on this point, the judgments of the High Court and Court of Appeal were set aside by a 6-1 majority (Ibrahim J the sole dissent); that is, the Supreme Court rejected the applicability of the basic structure doctrine and of the four-step sequential process in Kenya, by a 6-1 majority. I believe, however, that a close reading of the seven opinions reveals a somewhat more complex picture, which I will now attempt to demonstrate.

Hyper-Amendments and Tiered Constitutional Amendment Processes

In addressing the question of the basic structure, several judgments of the Supreme Court begin at a common starting point: what was the specific historical mischief that the Kenyan Constitution’s amendment procedures (set out under Chapter XVI) were attempting to address? The answer: a culture of “hyper-amendments” to Kenya’s Independence Constitution. In the years after Independence, the old Constitution was often seen as an impediment by the Presidency, and as a result, a series of far-reaching amendments were passed that more or less entirely devalued its status as a founding charter (and invariably concentrated power in the office of the Presidency, at the cost of other State organs and the People (Ouko J, paragraph 1918, quoting Ghai/McAuslan). Upon Kenya’s return to multi-party democracy in the 1990s, and the eventual constitutional reform process, this culture of hyper-amendments was prominently in the minds of the People and of the drafters (see Koome CJ, paragraph 189 – 191; Mwilu DCJ, paragraph 521; Lenaola J, paragraphs 1415 – 1417; Oukuo J, paragraph 1802).

In the years after Independence, the old Constitution was often seen as an impediment by the Presidency.

Up to this point, the opinions of the Supreme Court are in agreement with those of the High Court and the Court of Appeal. Drawing upon the historical record, the Supreme Court opinions then go on to argue that the Kenyan People therefore devised a solution to the problem of hyper-amendments, and constitutionalised it; in other words, the hyper-amendments were to be addressed by a solution internal to the 2010 Kenyan Constitution. This solution is to be found in Chapter XVI of the Constitution, and – in particular – in the tiered amendment process that it sets up. Article 255(1) of the Constitution “entrenches” certain provisions of the document. For these “entrenched” provisions, the amendment procedure is far more onerous than for un-entrenched provisions, requiring a referendum with certain conditions (Article 255(2)), in addition to (or complementing) the Parliamentary amendment route (under Article 256) or the popular initiative route (in Article 257). This tiered amendment process, according to the judges, thus creates a balance between constitutional flexibility and constitutional rigidity, and also “tames” the mischief of hyper-amendments (see Koome CJ, paragraphs 192 – 197; Ndungu J, paragraphs 1161 – 1162; Lenaola J, paragraph 1418; Ouko J, paragraph 1803).

Two conclusions follow from this, according to the Supreme Court. The first is that this history – and structure – of the 2010 Kenyan Constitution therefore distinguishes it from jurisdictions such as India (where the basic structure doctrine first gained judicial acceptance). In India, where Parliament possesses the plenary power to amend the Constitution, the basic structure doctrine arises as a judicial response in order to protect the Constitution from parliamentary abuse. However, what in India requires the basic structure doctrine, is already provided for in Kenya through the tiered amendment process; in other words, the tiered amendment process does the job that the basic structure doctrine is supposed to do (Koome CJ, paragraphs 217; Mwilu J, 401-402; Lenaola J, paragraphs 1439 – 1442, 1451 – 1453; Ouko J, paragraphs 1763 – 1781, 1811). And secondly, the tiered amendment process – and its history – demonstrates that the People – in their capacity as framers of the Constitution – intended to make the amendment process gapless.

The three pathways provided for under Articles 255 – 257 are exhaustive, and for this reason, the High Court and the Court of Appeal were incorrect to introduce a “judicially-created fourth pathway” to amendment (Koome CJ, paragraph 200). Koome CJ also frames this another way, noting that the High Court and the Courts of Appeal failed to demonstrate what the lacuna was in Chapter XVI that necessitated the judicial creation of the four-step process (Koome CJ, paragraphs 200; Mwilu J, 406).

This snapshot, I believe, is an accurate summary of the reasoning of a majority of the judges in this case. To my mind, however, it also raises two interlinked issues, which – when scrutinised closely – somewhat complicate the final holding of the Court.

Amendment, Repeal, and the Basic Structure

It is, of course, entirely correct to say that the plenary power of parliament to amend the Constitution (as in India) is significantly distinct from the tiered amendment process under Articles 255 – 257; and, further, that this distinction is relevant when considering the question of the basic structure. However, it is equally important not to overstate the sequitur: it does follow from this – as I have argued previously – that the version of the basic structure doctrine as developed in India (i.e., a judicial veto over amendments) cannot be transplanted into the Kenyan context. However, this was not what the High Court and Court of Appeal did. Precisely because of the tiered structure of amendments under the Kenyan Constitution, the High Court and the Court of Appeal articulated a much more reduced role for judicial review: not a substantive veto over amendments (thus making every provision potentially amendable), but a procedural role to ensure that alterations to the basic structure could be done only through the primary constituent power.

Secondly – and connectedly – this flows from a conceptual point that is left unaddressed by the summary of the Supreme Court’s argument that I have provided above: the distinction between amendment and repeal (express or implied). The tiered amendment process, the onerous requirements under Article 257 to prevent hyper-amendments, and the balance between flexibility and rigidity ensure that as a practical matter, in most circumstances, the basic structure doctrine will not need to be invoked, because the Constitution’s internal mechanisms are far more effective for dealing with potential constitutional destruction (as opposed to, say, the Indian Constitution). The fact that the basic structure doctrine will almost never need to be imposed does not, however, address the point that it exists because of the conceptual distinction between amendment and repeal, and the fact that the Constitution – as conceded by Ouko J – “does not provide for its own replacement” (paragraph 1847).

Precisely because of the tiered structure of amendments under the Kenyan Constitution, the High Court and the Court of Appeal articulated a much more reduced role for judicial review.

Now, how do the judges of the Supreme Court deal with this point? Let us first consider the judgments of Ibrahim J (formally in dissent) and Dr Smokin Wanjala J (formally in the majority). Ibrahim J’s judgment is straightforward: he agrees with the High Court and the Court of Appeal on the distinction between amend and repeal, the primary constituent power, and the four-step sequential process (see, in particular, paragraphs 724 – 725). Let us now come to Smokin Wanjala J, because this is where things start to get interesting. Wanjala J objects to the abstract nature of the enquiry that has been framed before – and addressed by – the superior courts below (paragraph 1000). He notes:

Speaking for myself from where I sit as a Judge, and deprived of the romanticism of academic theorizing, it is my view that what has been articulated as “the basic structure doctrine”, is no doctrine, but a notion, a reasoning, a school of thought, or at best, a heuristic device, to which a court of law may turn, within the framework of Article 259(1) of the Constitution, in determining whether, a proposed constitutional amendment, has the potential to destabilize, distort, or even destroy the constitutional equilibrium. (emphasis supplied)

But when you think about it, this is – essentially – the basic structure “doctrine” (or the “basic structure heuristic device” if you want to call it that), without being explicitly named as such. It is an interpretive method whose purpose is to prevent amendments that “destabilise, distort, or destroy the constitutional equilibrium.” Importantly, both here – and in his disposition – Wanjala J explicitly considers Article 259(1), which requires the Constitution to be interpreted in a manner that promotes its values and principles – as a substantive limitation upon constitutional amendments, in addition to the requirements of Chapter XVI. This is particularly clear from paragraph 1026:

In this regard, I am in agreement with the observations by Okwengu and Gatembu, JJ.A to the effect that a proposed amendment must pass both the procedural and substantive test. Where I part ways with my two colleagues is at the point at which they base their substantive test not on the constitutional equilibrium in Article 259, but on a basic structure (Gatembu, J.A–Article 255(1) and Okwengu, J.A–the Preamble). By the same token, I do not agree with the submission by the Attorney General to the effect that any and every proposed constitutional amendment would be valid as long as it goes through the procedural requirements stipulated in Articles 255, 256 and 257 of the Constitution. Courts of law cannot shut their eyes to a proposed constitutional amendment, if its content has the potential of subverting the Constitution. (emphasis supplied)

Now, with great respect, one may choose not to call something “the basic structure doctrine”, but the statement that a Court of law can subject constitutional amendments to judicial review on the question of whether its “content has the potential of subverting the Constitution”, one is doing what is generally understood to be basic structure review. It might be the case that its long association with the specific form taken in India has turned the basic structure doctrine into a bit of a poisoned chalice. In that case, there should of course be no problem in dropping the term, and simply stating that “constitutional amendments that subvert the Constitution are subject to judicial review.” And in his disposition at paragraph 1122, Wanjala J agrees that while the four-step sequential process will not apply to constitutional amendments, it would nonetheless apply to “seismic constitutional moments” when the People are exercising their primary constituent power.

It is an interpretive method whose purpose is to prevent amendments that “destabilise, distort, or destroy the constitutional equilibrium.”

We therefore already have a more complicated situation than what the final disposition of the Court suggests. That disposition suggests that a 6-1 majority rejected the basic structure doctrine. That is true, because Wanjala J does not believe that the basic structure doctrine is a “doctrine”. But we already have two judges who accept the distinction between constitutional amendments and constitutional repeal (or subversion), and accept that in the latter case, the primary constituent power (with its four-step process) will apply.

I now want to consider the opinions of Lenaola J and Ouko J. To their credit, both judges recognise – and address – the issue of constitutional amendment versus constitutional repeal. In paragraph 1464, Lenaola J states:

My point of departure with my learned colleagues is that the process presently in dispute was squarely anchored on Article 257 as read with Articles 255 and 256. I shall return to the question whether the Amendment Bill was in fact a complete overhaul of the present constitutional order or whether it was an amendment as envisaged by these Articles (emphasis supplied). Suffice it to say that, should the Kenyan people, in their sovereign will choose to do away with the Constitution 2010 and create another, then the sequential steps above are mandatory and our constitutional history will be the reference point.

Thus, in paragraph 1464, Lenaola J explicitly recognises the distinction between “a complete overhaul” and “amendment”, and also recognises that the 255 – 257 procedure only deals with the latter category. Indeed, his primary point is that the BBI Bill was not, as a matter of fact, a “complete overhaul”: in paragraph 1472, he asks, “why would dismemberment take centre stage when the issue before the courts below was amendment?” And most definitively, in paragraph 1473, he quotes Richard Albert’s distinction between “amendment” and “dismemberment”, with approval (paragraphs 1474 – 1475). Indeed, in the paragraph he quotes, Albert specifically notes that “a dismemberment is incompatible with the existing framework of the Constitution because it seeks to achieve a conflicting purpose” – lines very similar to Wanjala J’s articulation of constitutional “subversion”.

It might be the case that its long association with the specific form taken in India has turned the basic structure doctrine into a bit of a poisoned chalice.

There is, admittedly, something of an internal tension in Lenaola J’s opinion here: he appears, for example, to suggest later on that dismemberment necessarily requires formally enacting a new Constitution (see paragraph 1485). It is crucial to note, however, that this need not be the case: a Constitution’s structure and identity (the language used by Richard Albert, which Lenaola J cites with approval) can be “overhauled” by something as technically innocuous as changing a single sentence – or even a single word – in a single constitutional provision. For example, an amendment changing a polity from a multi-party democracy to a single-party State can be accomplished through a single sentence, but it is undoubtedly a constitutional dismemberment. Another historical example is the Indian Supreme Court judgment in Minerva Mills, where the Constitutional amendment at issue had essentially made the Indian Constitution’s bill of rights non-justiciable, as long as the government stated that it was carrying out a social policy goal. This had been accomplished by amending a part of a sentence in a sub-clause of one provision of the Indian Constitution.

A very similar tension is present in Ouko J’s opinion. In paragraph 1838, he notes:

Therefore, it is true to say that it is the prerogative of the people to change their system of government, but only by the people’s exercise of their constituent power and not through the amendment procedure. And that is the difference between primary and secondary constituent powers, the former is the power to build a new structure by the people themselves and the latter, the power to amend an existing constitution. Today, under Chapter Sixteen, this power is exercised by the people and their elected representatives.

Once again, we see the distinction between “amendment” and – in this case – “building a new structure” or “changing the system of government.” This comes to a head in paragraph 1846, where she notes:

It ought to be apparent from the foregoing that, I must come to the conclusion that a constituent assembly is an organ for constitution-making. An amendment of the Constitution under Chapter Sixteen does not recognize constituent assembly as one of the organs for the process. This Constitution, like the former Constitution does not contemplate its replacement.

And in paragraph 1849:

Therefore, the question to be determined here is whether the proposed amendments would lead to such egregious outcome. That they had the effect of repudiating essential elements of the Constitution—concerning its structure, identity, or core fundamental rights—and replacing them with the opposite features; a momentous constitutional change.

Once again, with respect, one may choose not to call this “basic structure review”, but what is happening here seems awfully close to “basic structure review” when courts or scholars do call it that. As with Lenaola J, Ouko J’s primary discomfort appears to be with the Courts below having labelled the BBI Bill as akin to constitutional dismemberment. In paragraph 1858, he labels this as “overkill”. The point, however, is that this admits the principle: if indeed any kind of formal “amendment” was possible under Articles 255 – 257, then the question of substantively assessing the amendments themselves wouldn’t even arise. Indeed, it doesn’t arise in Ndungu J’s opinion, which is very clear on the point that there is no constitutional alteration that is outside the scope of Chapter XVI.

An amendment changing a polity from a multi-party democracy to a single-party State can be accomplished through a single sentence, but it is undoubtedly a constitutional dismemberment.

Thus, we now have an even more complicated picture. Two judges out of seven (Ibrahim and Wanjala JJ) accept, in substance, the proposition that the four-step process applies to radical constitutional alteration that cannot properly be called an amendment. Two other judges (Lenaola and Ouko JJ) accept the principled distinction between constitutional “dismemberment” and “amendment”; Lenaola J appears to suggest that in the former case, you would need the four-step process, as it is akin to making a new Constitution, while Ouko J accepts Professor Akech’s amicus brief on the point that the four-step process was not, historically, how the 2010 Constitution was framed; it is only an “approximation.” Thus, we now have a situation where, in the disposition, six out of seven judges have rejected the applicability of “the basic structure doctrine”, but (at least) four out of seven judges have accepted that there is a conceptual distinction between constitutional “amendment” and “dismemberment”, the latter of which is outside the scope of Chapter XVI amendment processes (with three out of those four seeing space for the four-step process, and the fourth holding that it is an “approximation” of the founding moment).

What of the opinion of Mwilu DCJ? In paragraph 407, Mwilu J notes that:

In my view, whether a Constitution is amendable or not, whether any amendment initiative amounts to an alteration or dismemberment and the procedure to be followed is a matter that would be determined on a case to case basis depending on the circumstances.

After then noting the distinction between “amendment” and “alteration” (paragraphs 418 – 419), she then notes, at paragraph 421:

The court always reserves the constitutional obligation to intervene provided that a party seeking relief proves to the court’s satisfaction that there are clear and unambiguous threats such as to the design and architecture of the Constitution (emphasis supplied).

While this is also redolent of basic structure language, Mwilu J later goes on to note that while constitutional alteration must necessarily be an “extra-constitutional process” outside the scope of Articles 255 – 257, the exact form it might take need not replicate the manner of the constitutional founding: it may be through the “primary constituent power” or through “any of the other mechanisms necessary to overhaul the constitutional dispensation.” (paragraph 437)

It is not immediately clear what these other mechanisms might be. Mwilu J’s basic point appears to be that the mechanism by which fundamental constitutional alteration takes place cannot be judicially determined, as it is basically extra-constitutional. The corollary of this surely is, though, that to the extent that these fundamental alterations are sought to be brought in through the amendment process, they are open to substantive judicial review, as Mwilu J explicitly notes that those kinds of alterations “are not subject to referendum” under Article 255. In other words, Mwilu J’s problem appears to be not with judicial review of formal constitutional amendments in order to decide whether or not they are fundamental alterations, but with what follows, i.e., the judiciary deciding that, in case it is a fundamental alteration, that it must be done through the four-step test. But the only other alternative that then reconciles all these positions is for the judiciary to invalidate radical constitutional alteration that is disguised as an amendment via the 255 – 257 route; in no other interpretation does paragraph 421, which calls for judicial intervention when the threat is to “the design and architecture of the Constitution”, make sense.

We now have a situation where, in the disposition, six out of seven judges have rejected the applicability of “the basic structure doctrine”.

Finally, what of Koome CJ’s opinion? While Koome CJ is clearest on the point of the tiered amendment process achieving the balance between rigidity and flexibility, her judgment does not address the distinction between “amendment” and “repeal.” In paragraph 226, Koome CJ notes that any amendment to the Constitution must be carried out in conformity with the procedures set out under Chapter XVI; but that leaves the question unaddressed – what if it is alleged that the impugned amendment is not an amendment, but an implied repeal? In her summary of findings, Koome CJ notes further that the basic structure doctrine and the four step process are not applicable under the Constitution (paragraph 360). This is true, but also in substantial agreement with the case of the BBI challengers: the basic structure doctrine does not kick in as long as the formal amendment is actually an amendment, and as long as we are within the existing constitutional framework. It only applies when we are no longer under the Constitution.

Conclusion

Formally, by a majority of six to one, the Supreme Court rejected “the applicability of the basic structure doctrine” in Kenya. However, as I have attempted to show, a close reading of the seven judgments reveals a more complex picture. Consider a hypothetical future situation where a proposed amendment to the Constitution is once again challenged before the High Court, on the basis that it is not an amendment at all, but implied repeal, or repeal by stealth, or constitutional dismemberment. When the High Court looks to the Supreme Court for guidance, it will find the following:

- A majority of six rejecting the applicability of the basic structure doctrine (from the disposition)

- A majority of five accepting the distinction between “amendment” and “repeal” or “dismemberment”.

- A plurality of three explicitly noting that this distinction is subject to judicial review (with two others not taking an explicit position on this).

- A plurality of three holding that in case an “amendment” is actually a disguised “repeal”, the four-step test will apply (with an equal plurality of three against it, and one – Koome CJ – silent, as she does not draw a distinction between amendment and repeal).

In such a situation, how will the High Court proceed? That, I think, is something that time will tell.

Two final remarks. I think that a close reading of Koome CJ’s judgment came close to resolving the bind outlined above, without explicitly saying so. In paragraph 205, she notes:

The jurisprudential underpinning of this view is that in a case where the amendment process is multi-staged; involve multiple institutions; is time-consuming; engenders inclusivity and participation by the people in deliberations over the merits of the proposed amendments; and has down-stream veto by the people in the form of a referendum, there is no need for judicially-created implied limitations to amendment power through importation of the basic structure doctrine into a constitutional system before exhausting home grown mechanisms.

Koome CJ dwells at length upon the extent and depth of public participation required under Articles 256 and 257, and effectively equated the process with the four step test, sans the constituent assembly: running through her judgment is a strong endorsement of the civic education, public participation, and referendum (after adequate voter education) prongs of the test. What this suggests is that it might be open to argue that the procedures for participation under Articles 256 and 257 do not codify the primary constituent power (because that is a conceptual impossibility), but reflect it. In other words, if you are following the procedures under Articles 256 and 257 (in the sense of deep and inclusive public participation, as set out in Koome CJ’s judgment, and we will discuss some of that in the next post), you are exercising primary constituent power, and therefore, fundamental constitutional alterations are also possible as long as public participation happens in all its depth. This, I would suggest, might reconcile some of the potential internal tensions within some of the judgments, and also essentially keep the High Court and Court of Appeal’s judgments intact, just without the Constituent Assembly.

Secondly, one thing that appeared to weigh with the Court was the fact that in the twelve years since 2010, there has been no successful attempt to amend the Kenyan Constitution, and all attempts – whether under Article 256 or Article 257 – have failed. This is true; however, what is equally true is that were the BBI Bill to succeed, we would go from no amendments in twelve years to seventy-four amendments in twelve years, making the Kenyan Constitution one of the most swiftly-amended in the world. If it is true, therefore, that the purpose of the tiered amendment structure is to find a balance between flexibility and rigidity, while also ring-fencing entrenched provisions, then this has certain inescapable conclusions for the interpretation of Article 257 – including the question of single or multiple-issue referenda. This will be the subject of the next two posts.