In my open letter to Kenyans, I talked about how the arts are a divine calling. The arts make us human, because the arts provide a space for us to be social and individual at the same time. With the arts, we accept what we can’t change and change what we can, while producing something creative and sometimes new.

Let me give an example of what I mean. The rituals we perform when someone we love dies help us accept death as something we all must face. However, we cannot raise our hands and say death is inevitable, because if we do, we would not have reason to live our lives to the fullest. So the arts is where we deal with that contradiction. When Amos and Josh sing “Tutaonana baadaye”, they are singing, “We accept your going is inevitable, but until we join you, we must still live our best lives, love with all our hearts.” And from this deep truth, Amos and Josh and King Kaka produced a beautiful song.

That’s what the arts are – beauty that carries deep truth.

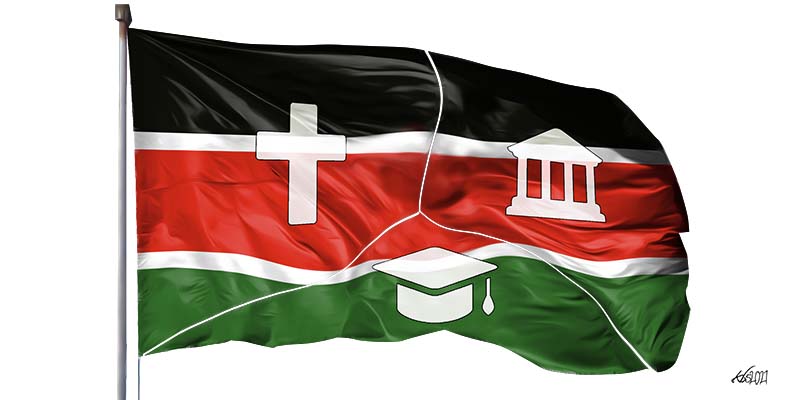

This beauty that carries deep truth is not liked by the people who want power. For them to be powerful, they must block us from the truth, and so they block us from the arts. The people in power combine the force of education, religion, business and media to make sure that either they block us from the arts, or they distort the arts so much that the arts don’t lead us to the truth but to a false impression of the truth.

So I’m going to talk about how education boosts this system.

The thing to remember is that the school system hates the arts for the same reason that the government hates them. Schools have structures of power, like principals, who in turn have their deputies and middle-level managers. The power they exercise is no different from that of the state, and in fact, in many instances their appointments are made by the state.

So the education system hates the arts for the same reason as politicians, the clergy and business people: arts will make teachers and students start asking questions about the education system, including questions about content and whether we must use violence to educate. For this reason alone, schools do not want arts education because it would make teachers and students less easy to control.

And how does the education system fight against the arts? By capturing and telling lies about three things: education, work, the arts.

Lies about education

The biggest lie that has been told to us is that schooling = education. I’m sure you know this, because I hear artists saying it, except that it doesn’t mean what they think it means.

Let’s start by defining education. Education is the formal way in which people expand their knowledge and refine their skills. In other words, education is done deliberately. This means two other truths that Kenyans, including artists, seem not to fully understand.

One, that people can expand their knowledge and refine their skills unconsciously, through life, habit and experience. In this letter, I will call that process “culture”. In other words, you may learn to dance not because you deliberately decided to learn, but because dancing was happening around you and you also learned to dance. The fact that you did not learn your knowledge or skill consciously with the purpose of becoming a dancer does not mean that your knowledge and skill are less important than what others learn in the formal school. Culture was just another way of learning for you.

Two, formal learning is not restricted to going to school alone. Formal learning includes apprenticeship and mentorship. When we are mentored by or apprenticed to someone else, we are going to school, even though we are not sitting in a classroom to be taught by someone called a teacher, and then getting a certificate for it. One of the reasons why I used to invite artists to meet my students is because I wanted my students to hear that even other artists put time into learning their craft from others. So we heard from Juliani that he learned his craft from Ukoo Flani, or from Suzanna Owiyo that she learned to play the nyatiti from her grandfather.

So it is extremely important, and I cannot emphasize this enough, that artists must learn from others. When our artists are not being mentored artistically by anybody, we have reason to worry.

I have heard some artists say on TV that they didn’t learn their craft from anyone. I find that upsetting, because even if they didn’t go out deliberately to learn from elders the way Juliani and Suzanna Owiyo did, they were learning from what was being played in the house or what they heard or did as children. By saying they did not go to school, they are basically dissing their cultures and backgrounds. Or they don’t know them at all.

When we are mentored by or apprenticed to someone else, we are going to school, even though we are not sitting in a classroom to be taught by someone called a teacher.

But the second reason why that statement is upsetting is because it means that such artists see no value in creating arts traditions or archives. It means that if you didn’t learn from anyone, no one needs to learn from you. That means that we will always start our arts from scratch, over and over again. It means that with the arts, we are always reinventing the wheel. And the people in power like that, because the larger society never builds an archive of knowledge.

And without an archive of knowledge about the arts, society has no obligation to respect the arts as work that people spend their time doing, or that it is a skill they learn. And I’m sure you can know the rest of the story. But I’m going to go over it.

Lies about work

The second lie that the education system tells us is that going to school is for employment, and employment is for national development. And we artists know the second part of that lie: to develop, we don’t need the arts; we need STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics).

And to support these lies, the educators and the media tell us junk like 80 per cent of students are in arts subjects. It’s not true. Let me just give the worst example of arts education in Kenya: out of 70 universities in Kenya, only six universities teach music. Only one university teaches fine arts. There is no Master of Fine Arts degree in Kenya.

But the other problem with the lie about employment is that without arts education, we are not able to teach generations of Kenyans to appreciate the importance of arts in society, whether they become artists or not. We need to teach arts education to create a society that will support artists. In other words, if we want the Kenyans to buy your albums, your books and your paintings, to go to the cinema to watch your films and to the theatres to watch your plays, they need to have grown up learning the importance of the arts for their own lives and for society as a whole. They need to understand the importance of protecting public parks and social halls where musicians can perform. They also need to understand the work that goes into art, so that they stop negotiating with you to pay almost nothing, if they pay you at all.

When you go on TV and talk badly about schools and not needing to go to school to be an artist, you are encouraging schools not to provide arts education, so that the next generation of farmers, engineers, lawyers, doctors, teachers will not spend their resources paying for your work. In other words, you are encouraging people not to see your work as work that needs to be paid for. So please think again before talking badly about schools.

When you go on TV and talk badly about schools and not needing to go to school to be an artist, you are encouraging schools not to provide arts education.

Also, when the school system says that the only work worth respect is the work you went to school for, we are encouraging schooling-based discrimination. There is a lot, a lot of work done in Kenya, not only by artists, but also by people who did not get certificates in order to do it. The rich still profit from that work, but they pay even less for it because the workers did not learn it in school. That is why the government is actively discouraging people from pursuing university education. They want Kenyans to learn university level work but not pay them for the value of their work. This problem is no longer about artists alone. It’s affecting all young people.

So the lesson here is 1) value your education, even if you did not get it in the school system, and 2) do not diss the school system as irrelevant to the arts.

Lies about the arts

This third lie about the arts is repeated by artists so much, it’s embarrassing. The lie that the arts are about “talent”. The problem with “talent” is that it suggests that arts is not work that takes skill and time. In fact, businesspeople exploit artists precisely because of the attitude that “Why do you want me to pay for just shaking your body around or splashing colour on a canvas? Si it’s just talent? Even I can do the same work if I wanted to.” For them, performance has no rehearsals, painting has no sketches, and writing has no drafts. You’re just talented. Your art required no work or skill.

This lie was picked up by the Kenya Institute for Curriculum Development, so that you believed the government when it said that Competency-Based Curriculum is different because it will have a pathway for the “talented” students who do not do well in the sciences. How on earth could you accept such madharau as “arts education”? And yet, as I explained on Citizen TV, the “talent” pathway is where they are going to throw the kids who are poor or needed extra help from teachers. In other words, the arts are the place to dump the students let down by the education system.

With that kind of attitude expressed about the arts, we should not be surprised that professionals coming out of the school system don’t see the arts as worth paying for.

But there is another insidious thing happening within the education system that should make us very worried. We are producing periphery professionals without the core artistic skills. Universities, for example, are producing film-makers who don’t learn to tell stories, journalists who don’t learn language or how to write, conflict experts who have no knowledge of history, politics and anthropology, or musicians who cannot play instruments. How is this acceptable?

It is acceptable because the universities have bought the lie that the arts are not “marketable” and are not investing in teaching these subjects. So universities are cheating students that they will produce good films and produce good music without learning story-telling and composition work.

And as a country, we pay the price for this mess with our inability to produce art that we Kenyans can be proud of and that can put us on the international map. For instance, Hollywood makes its biggest and most award-winning films from stories of real people, or from their own novels and plays. Lupita Nyong’o won her Oscar for a film based on a real-life story.

But year after year, Kenyan film-makers guilt-trip us into watching local films but are yet to produce the story of Wangari Maathai or Syokimau or Elijah Masinde on screen. We have few of our oral stories in cartoons, and instead we watch Lion King. By now the column “Surgeon’s Diary” should be an ER-type series, “Mwalimu Andrew” should be a sitcom. But why can’t Kenyan filmmakers think like this? Because they don’t study stories. They study cameras and scripting and Western film festivals. Remember what I said about “reinventing the wheel?” That is what we do.

The last concern I have about education is the most serious of all. This one pains me.

Arts in Kenyan education is taught like science. Literature, the most prominent example, is taught so badly, that students leave school hating it. They are not taught to enjoy stories for what they are.

There are three main ways in which literature is taught. One is to cut up literature scientifically into themes, characters, style and other details and make students repeat those analyses without ever enjoying or understanding the story. The other is to insist on morals, a development agenda or a specific anti-colonial story. The last is to shame students into saying they have no identity because they don’t know the songs their great-grandparents used to sing.

The purpose of all these methods is to prevent the type of arts I talked about in the previous letter. It’s to prevent individual enjoyment and expression through the arts. It’s also to reinforce the idea that the arts are not for us, human beings, but for grades (the school), the church (morals), the state (development) or politics (limited to anti-colonialism).

We pay the price for this mess with our inability to produce art that we Kenyans can be proud of and that can put us on the international map.

This view of the arts explains some disturbing things I notice in my classroom. Our students can’t enjoy art or talk about real life. For instance, when I recently gave some love poems for students to analyze, they said that the praise of a loved one was a lie or an exaggeration. These days, when we are in class, students will tell me about fascinating things in society, but when they hand in the write-up, I find they have not written what they said in class, but have written notes like a schoolteacher. One class finally got what I was complaining about when I said that in Kenya, if I wear a nice dress, people will not say, “That dress is beautiful” or “You look nice.” They will give an analysis: “I always find kitenge dresses very smart.” That’s how disconnected the Kenyan psyche has become. We’ve lost our human warmth.

When the arts are not about us, human beings, but about institutions, then we become an autocratic society. When the arts are treated in this way, it gives permission to the government to censor us, to businesses to exploit us, to churches to condemn us, and to society to not value us. And the price the whole society pays is the loss of our soul.