So far, Africa is well behind the curve in terms of the coronavirus infection. At the time of writing, there were 1,388 confirmed cases on the continent out of just over 320,000 confirmed cases globally. Four North African countries – Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco – had 679 cases, which represented about half of the total cases in Africa. South Africa alone had 240 cases, and there were 479 reported cases across 39 African countries.

It is as yet unclear why the numbers in Africa are so low, although several South Asian countries close to China have similar low numbers. Candidates include high temperatures, low international travel (Africa accounts for only 2 per cent of global air travel), limited testing, and the youthful population, which could be infected but not exhibit symptoms.

The so-far-so-good numbers notwithstanding, African countries are not taking chances, and are adopting the same measures as elsewhere – outlawing large gatherings, closing schools, restricting air travel, and so on. These actions are welcome because they have raised awareness in a way that messaging alone would not have, proof positive that actions speak louder than words.

We need to get a better sense of the actual infection rate. Are the low numbers real or a result of under-testing? Establishing definitively whether the virus is spreading locally or not is imperative.

Living arrangements in many urban settings will make it difficult for infected people to isolate themselves. If there is already community transmission, then the best strategy is containment. If or where there is none, then decongesting the urban areas by encouraging people to temporarily relocate to their villages should be considered. It seems to me that this can be established by purposive sampling of people and population clusters with the highest exposure to international travel, such as airlines, airports, international hotels, and tourism hot spots. This is critical.

Medical resources are a huge survival factor. Patients who are put on ventilators have a high survival rate, but these are in short supply. As I write, Germany has lost 94 people out of 25,000 (one per 265), while France, with 16,000 cases, has lost 674 (one per 24). Both countries have similar demographic profiles, but Germany has two and a half times more intensive care beds (29 per 100,000 people) than France (11.6 per 100,000 people). This implies that if 100 patients need intensive care beds at once, Germany could save all of them, but France could lose 60. Italy’s capacity is about same as France’s, at 12.5, but the U.K’s, at 6.6, is less than a quarter of Germany’s. This is a huge and somewhat startling difference between countries that we in the global South see as more or less equally developed.

Living arrangements in many urban settings will make it difficult for infected people to isolate themselves. If there is already community transmission, then the best strategy is containment. If or where there is none, then decongesting the urban areas by encouraging people to temporarily relocate to their villages should be considered.

Most sub-Saharan African countries have less than one bed per 1,000 people, and less than 2 intensive care beds per 100,000 people. Because of our youthful population, we may not need as much capacity as Europe’s older population. Still, if one per cent of the population gets infected and 5 per cent of the infected population needs hospitalisation, this translates to a requirement of one bed per 2,000 people, which is more than half the total bed capacity in many countries. If 10 per cent of those hospitalised need critical care, this translates to a requirement of 5 intensive care beds per 100,000 people. We simply don’t have them. And there isn’t much lead time to scale up bed capacity. Moreover, with global supply chains and international trade severely disrupted, and demand surging everywhere, we can expect procurement of medical equipment to be a challenge during the crisis.

Countries will have to plan how to respond with the resources available. They need to make contingency plans on how they will mobilise facilities quickly if required. For example, one or more hospitals in a catchment area could be designated as coronavirus response facilities and trigger points when non-coronavirus patients would be evacuated to other facilities. In countries with a diverse mix of public and private hospitals, it may be necessary to pool and centrally coordinate utilisation so as to ensure maximum availability and optimal resource allocation. A class-based health system, such as the one we have in Kenya, is a luxury we may no longer be able to afford.

Africa and the 2020 global financial crisis

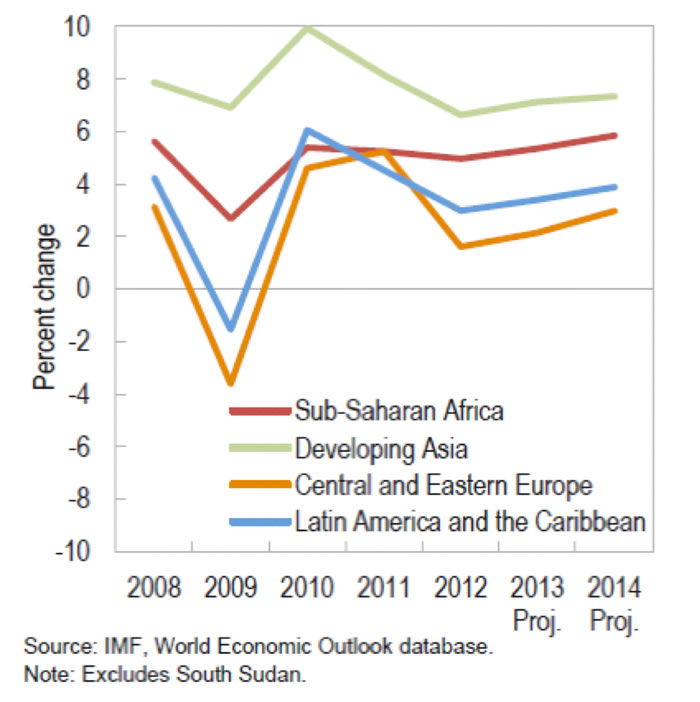

The global economic shock triggered by the coronavirus pandemic is unprecedented in scale and severity. While the 2007-08 global financial crisis was very severe, and its aftershocks are still reverberating, Africa was not severely affected. The impact, as measured by GDP growth, was less than that felt in all other developing regions, except Asia (due to the China effect).

Africa also recovered faster (see Chart. 1). There are two reasons for this. First, the shock was financial, and Africa was – and still is, for the most part – the least globally integrated region financially. Second, Africa’s public finances were in very good shape prior to the crisis, with low debt and low deficits, which made governments well-positioned to roll out aggressive stimulus packages. Third, China’s aggressive stimulus package kept the demand and prices of primary commodities buoyant.

Typically, economic shocks are either external or domestic, seldom both. This shock is both, and the two dimensions are mutually reinforcing. It has two global dimensions: trade and finance.

The trade shock is already affecting Africa through export earnings. Oil-dependent economies, such as Angola and Nigeria, are already looking at oil prices below $30 (down from $70 at the beginning of the year). If these prices persist, they will seriously impair government revenues and the servicing of external debt. Countries that are heavily dependent on tourism and fresh produce exports (notably, those in East Africa), are looking at heavy losses too.

We noted that Africa survived the global financial crisis bullet largely unscathed in part because of low global financial integration. This is no longer the case. After 2007, several African countries entered the sovereign bond market, known as Eurobonds. Before 2007, only two sub-Saharan African countries – South Africa and Seychelles – had floated international sovereign bond markets. Today there are more than 20 countries that have issued Eurobonds with an outstanding value of over $100 billion.

In addition, many countries have also borrowed heavily from foreign banks in the form of syndicated loans. Kenya is a good example. It has $10 billion of foreign commercial debt divided equally between Eurobonds and syndicated bank loans. A decade ago, Kenya had no foreign commercial debt. Commercial debt now accounts for a third of the country’s foreign debt.

These bond-issuing countries are now heavily dependent on global financial markets to finance their budgets, and more importantly, to refinance the bonds when they mature. How they will fare depends on how markets react to the crisis in the coming months.

Typically, economic shocks are either external or domestic, seldom both. This shock is both, and the two dimensions are mutually reinforcing. It has two global dimensions: trade and finance.

After the 2007-08 global financial crisis, the markets, awash with liquidity released by central banks, and facing recession and low interest rates in mature markets, turned to emerging and frontier markets for higher returns – “hunting for yield”, as they call it. If the markets do the same, then the financially exposed countries may weather the crisis unscathed. But given the systemic nature of the underlying economic crisis, money could well take “flight to safety”, in which case defaults will loom large.

Where things go from there will depend on how much external financial support from international finance institutions – bailouts if you like – will be available. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has announced that it could make up to $50 billion available quickly to low-income and emerging market countries. This is not much – it’s less that the IMF’s 2018 bailout package to Argentina ($57 billion). Besides this, the IMF can lend its members normal loans of up to a total of a trillion dollars. (A trillion dollars is in the order of 1.2 per cent of global GDP) Although the IMF uses a complicated formula for each country’s quota, I will use pro rata to illustrate how the IMF might allocate bailouts. On a pro rata basis, Nigeria could borrow $4.5 billion, Kenya could borrow $0.8 billion and Ghana could borrow $0.5 billion. By way of comparision, Kenya’s lapsed precautionary facility was $1.5 billion, while the facility recently extended to Ethiopia is $2.7 billion. If every emerging market needs a bailout as a result of the financial crisis, there won’t be enough to go round.

There is, however, another source of financing that is yet to be talked about, namely, moratoria on bilateral and multilateral debt service. Historically, the multilateral agencies (i.e. World Bank, IMF and African Development Bank-AfDB) are treated as preferred creditors whose debt is non-negotiable. In reality, countries in distress do build up arrears. In terms of substance, a moratorium on repayment translates to the same thing as extending new budget support loans. China, which is now taking the lion’s share of debt service for many countries, could demonstrate that it is indeed a friend of Africa by giving African countries some breathing space on debt repayments.

Economic stimulus measures, and why they may not work

Africans who are following economic developments globally and seeing Western governments rolling out economic “stimulus” measures are wondering whether African governments will be able to do the same. It is worth reiterating the fact that this is an unprecedented economic shock. That Western countries are doing their thing does not mean they’ve got it right. In fact, one may recall that economic pundits predicted that Africa would be the worst hit by the 2007-08 global economic crisis. Early on in the current crisis, none other than Bill Gates said that special attention should be paid to Africa, warning that if the coronavirus spreads here, more than 10 million people could die. The United Nations Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, has made a similar dire prediction.

I do not mean to downplay the threat, but Mr.Gates seems to have been blindsided by Afropessimism and was not prepared for the fact that his home state in the United States would become one of the epicentres of the pandemic well ahead of Africa. I am not disputing that Gates’s prognosis is wrong, as much as I hope he is wrong. I am pointing out that he, among other Americans, not least the Commander-in-Chief, underestimated the threat to the United States.

Kenya has $10 billion of foreign commercial debt divided equally between Eurobonds and syndicated bank loans. A decade ago, Kenya had no foreign commercial debt. Commercial debt now accounts for a third of the country’s foreign debt.

Until recently, the UK was out on its own pursuing a “herd immunity” strategy that delayed intervention. If the great transatlantic powers can get the public health response wrong should be reason enough to be circumspect about their economic responses as well. Everyone is flying by the seat of their pants.

Consider economic stimulus measures. Economic stimulus measures are of two types: fiscal and monetary. In fiscal measures, the government borrows and spends. In monetary measures, central banks inject money into the economy using open market operations while simultaneously lowering interest rates. Fiscal measures work directly – once the government has spent the money, its in circulation. Monetary measures work indirectly – central banks inject the money into the banking system and hope that businesses and consumers will borrow and spend. We call both of these demand management tools because they increase purchasing power in the economy.

Injecting money into the economy is predicated on supply response, and herein lies the problem with this crisis. First, people who are social distancing or in lockdown are not going to go out to spend. Second, social distancing and lockdown also disrupt supply. For example, commercial aviation is grinding to a halt. Moreover, we don’t know how long this will last. The instinctive reaction of people to economic uncertainty is to save rather than spend, hoard rather than consume, what John Maynard Keynes famously named the “paradox of thrift”.

Unsurprisingly then, Western governments are progressively moving away from generic demand management to social safety net-type interventions. The UK has announced a wage subsidy scheme where the government will pay 80 per cent of the salary of employees who are unable to work if companies keep them employed. That looks uncannily like a suggestion I floated weeks ago – an interest-free lifeline fund to protect jobs (see tweets). There is also a proposal by House Democrats to give cash transfers to middle and low income families, starting with $2,000, and subsequent transfers based on how the crisis unfolds.

Demand management tools are not fit for purpose. In addition to financial relief, Govts should consider a lifeline facility to keep workers on payroll. Depending on how long this goes on, Govts should start thinking in terms of wartime economic mngment i.e central coordination. https://t.co/7yVOCSyOYA

— David Ndii (@DavidNdii) March 16, 2020

Will African governments be able to do this? Obviously, having floated the idea, it follows that I am convinced it can be done – at least on a limited scale. Let’s see how the numbers stack up.

Under normal circumstances, fiscal stimulus usually entails deficit spending to the tune of between 1 and 2 per cent of GDP. Kenya’s current GDP is in the order of Sh10 trillion ($100 billion), so a stimulus would be between Sh100 and Sh200 billion (between $1 billion and $2 billion). The average monthly wage, as reported in the Government’s 2019 Economic Survey report in the formal wage sector was Sh60,000 ($600) in 2018, while the minimum urban monthly wages ranged from Sh7,200 (US$72) to Sh27,000 ($270), with an average of Sh16,800. (Data on wages in the informal sector, which accounts for 85 per cent of the 18.5 million non-farm workforce, are not collected, but if they were, they would look like the gazetted minimum wage figures rather than wages in the formal sector.) The weighted average of the two is Sh23,300, which we can adjust for inflation to Sh25,000 (US$250).

At an average of Sh25,000, a one per cent of GDP jobs lifeline can pay 4 million workers – a fifth of the workforce – for one month. Obviously, we are looking at more than a month, probably three to six months. It would cover 1.3 million for three months and 660,000 workers for six months. These numbers are very significant. And, of course, the lifeline would not have to be 100 per cent of the pay. A 50 per cent lifeline increases the potential coverage to 2.6 million and 1.3 million workers for three and six months, respectively.

Injecting money into the economy is predicated on supply response, and herein lies the problem with this crisis. First, people who are social distancing or in lockdown are not going to go out to spend. Second, social distancing and lockdown also disrupt supply.

Trouble is, Kenya’s budget deficit is already way past the red line. The red line is 5 per cent of GDP. At the onset of the 2007-08 financial crisis, the budget deficit was running at below 3 per cent, which meant that the government had a headroom (referred to as fiscal space) of 2 per cent of GDP before reaching the red line. We are currently operating in the 7 per cent to 8 per cent range.

The deficit in the last financial year was 7.9 per cent. The target for this year was 6.3 per cent, but it’s projected at 7.6 per cent. The difference between 3 per cent and 7 per cent of GDP may not look that big but consider the following: When the deficit was 3 per cent, revenue was 18 per cent of GDP, government was spending 17 per cent more than its income. With revenue now down to 15 per cent, a 7 per cent of GDP deficit means that the government is spending 46 per cent more than its income.

We have been at it for six years. We are already on borrowed time. Already, the government’s domestic borrowing target this financial year has been revised upwards by more than Sh200 billion (US$2 billion), from Sh300 billion ($3 billion) to Sh514 billion ($5.14 billion) to plug in the gap left by planned foreign commercial borrowing of 200 billion ($2 billion) that, for whatever reason, the government has not raised. We also have to take into account that the Kenyan government is taking a hit on the revenue side, so the deficit is widening as it is, unless it cuts spending drastically – and it’s not good at that. An extra one percent of GDP domestic borrowing could just be the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

At an average of Sh25,000, a one per cent of GDP jobs lifeline can pay 4 million workers – a fifth of the workforce – for one month…A 50 per cent lifeline increases the potential coverage to 2.6 million and 1.3 million workers for three and six months, respectively.

Where does that leave us? Well, the prudent thing to do is to finance the lifeline within the existing deficit by re-allocation. The alternative is to go the monetary route – look at how banks can finance it. The most direct route is to allow banks to temporarily trade government bonds for cash with the Central Bank of Kenya in transactions known as repurchase agreements (REPOs). The drawback is that the banks will be exchanging low risk assets for high risk ones, and the non-performing loans (NPLs) ratio is already in alarm bell territory.

We go back to fiscal. All it requires is the political resolve to mothball development projects – after all, budget absorption will also be affected by lockdowns and social distancing. And infrastructure is not that urgent. And we may not require as much as Sh100 billion. My intuition tells me that half that amount – if well-targeted – will make a huge difference.

Africa’s urban sociology

Four years ago, I wrote an op-ed on the urban sociology of Africa, which is enjoying a small revival in the wake of a mass exodus from the city of Nairobi to rural homes. In Kenya, “home” means rural origin; we call urban residences “houses”. The article opened with an anecdote about how the disappearance of the entire population of Brazzaville following the outbreak of political violence in 2007 puzzled the humanitarian relief sector in the UK (where I was at the time) as it was gearing up for an emergency that never was. The frantic search for a displaced population in distress in the environs of Brazzaville was fruitless. The people had simply gone “home”. I wrote:

After a brief hiatus in the fighting following a truce that did not last, the residents began to trickle back carrying the usual rural goodies – bananas, yams, live chicken and so on. The international humanitarian agencies’ initial puzzlement is understandable – the idea of the population of Brussels or Copenhagen doing a vanishing act is inconceivable. [But] in Nairobi, as in Brazzaville, we travel light, and with an exit plan.

The migration in Kenya has already begun. It was inevitable. Many of the small businesses that urban residents rely on – eateries, hair salons and barber shops, metal and furniture workshops, motorcycle taxis – have already cratered, and it is early days yet.

But there is fear that, as most of our old people live in rural areas, retreating there will expose them to the virus. This then underlines the importance of aggressive tracing and testing to establish whether indeed we are still ahead of the curve or it’s a case of under-testing. If the virus has not yet spread, then it is better for those who cannot support themselves in the city to leave sooner rather than later. If we accept that it is impossible to practise effective social distancing in congested urban neighbourhoods, and informal settlements in particular, then surely the best way people can protect themselves is to go home where they have more space. If a person needs to be isolated, most rural homesteads will have a room that can isolate an infected person, or if not, a hut can be constructed in a day.

Watch: The Political Economy of Coronavirus: Dr David Ndii Speaks

A tricky thing about the pandemic is that its devastating economic effects come not from its virulence but from its contagiousness – its ability to spread without symptoms, more like HIV than Ebola. Emerging scientific evidence suggests that it has been spreading faster in cold weather, which means that it could oscillate between the Northern and Southern hemispheres for a couple of seasons until global “herd immunity” is achieved. National isolation and social distancing may become the new normal for a while.

How economic globalisation, the North-South development-underdevelopment paradigm, and Africa’s rural-urban socio-economic dynamics emerge from this, only time will tell.