You may be familiar with the common myths about drylands—that they contribute little to biodiversity and food systems, that they are unproductive and unworthy of political and economic investment, and their inhabitants are most responsible for this degradation. In the last thirty years, scholars, activists, and other actors have offered comprehensive counter-arguments and counter-narratives to these misconceptions. Here are a few facts: nearly half of the African continent is comprised of drylands ecosystems; twenty million pastoralists and agro-pastoralists live in the drylands of the Horn of Africa; in Kenya, arid and semi-arid lands are 80 per cent of the country’s landmass, inhabited by nearly ten million people. Researchers show that traditional pastoralism is likely one of the most adaptive productive strategies for Africa’s rangelands. There is much to learn from the flexibility and innovation of the resource-efficient communities that are sustaining pastoralism as a resilient livelihood.

Still, vulnerability in the drylands is rising. This is due to a complex mix of factors, including climate change and the economic fallout from COVID-19. Disruptions to the food supply chain together with continued drought—likely the worst in 40 years—are putting lives and livelihoods at risk. In Kenya, the World Food Programme has warned that half a million people are currently on the brink of a hunger crisis, and the number of Kenyans requiring assistance has quadrupled in two years. As governments, community leaders, and humanitarian agencies respond to urgent crises, we must resist longer-term proposals solely predicated upon sedentarization. The agro-centric and teleological perceptions informing these “solutions” are at best incomplete, and destructive at worst. Such a narrow view of pastoralist systems obfuscates the sophisticated social technology which undergirds them. Pastoralism’s core capability of “boosting and amplifying process variance with real-time management strategies and options” enables pastoralists—Emery Roe’s pithy “reliability professionals”—to identify and test new ways to sustain livelihoods uniquely well in contexts of high uncertainty. The system behind such rapid feedback loops of identifying, assimilating and responding to variability and risk is radical. When the source and paths of uncertainty are inconceivable and resulting changes incommensurate— in other words, when even the illusion of prediction and control is impossible— then coping reactively is a moot option. Settled societies would do well to apprentice with pastoralists on “coping ahead”.

Collective ownership and shared labour, in pasture surveillance and livestock protection for example, make long-term resource management through mobility viable. This is what doctoral researcher Tahira Shariff terms the “moral economy” underpinning pastoral production. Shariff cites the Borana proverb “borani wali waheela amalle walii wareega” to illustrate the individual’s loyalty to the group: “I exist because you exist”. Once we fully dispel the correlating myths of pastoralists as culturally outmoded Luddites, isn’t it clear that this is an innovative and sophisticated pastoral (social) technology?

While an important contribution to the popular and policy narratives on pastoralism, cogent explorations of this social technology could also guide other urgent issues of livelihood vulnerability, governance, conflict, and shared resource management. Practically: are early warning tools designed for pastoralist communication strategies? Is how drought is perceived, and talked about, central to drought management projects? How does group decision-making function, and can it be influenced, say to resolve conflicts among pastoralist communities? How and where (or with whom) are inherited pastoralist insights on climate forecasting preserved? Are livelihood decisions affected by changing social networks and hierarchies?

Recent work coalescing around this is exciting: Dr Jaro Arero and Dr Hussein Tadicha make the case for integrating indigenous knowledge for climate information. Community radio stations—Like Fereiti FM, the first Rendille language station in Marsabit—are driven by citizen reporting like that behind the Kenya Pastoralist Journalist Network. Yusuf Ibrahim highlights how the use of indigenous language has enabled community radio to become a reliable source of information. An example of the novel ways mobile phones extend the realm of social networks is the discovery in 2018 that Maasai pastoralists in northern Tanzania create new social ties through wrong number connections on their phones.

The material and emotional benefits of belonging to a social network, whatever the channel, are immense. The varied aspects linked to the pastoral technology of relating to each other and their ecosystem can be simplified as a factor of communication. Ongoing research under the Supporting Pastoralism and Agriculture in Recurrent and Protracted Crisis (SPARC) programme finds that social media, mostly through mobile phones, is the fast-growing corollary to community radio in pastoralist Kenya. Social media opens up further possibilities to better understand and learn from the communication strategies pastoral communities use to update and transmit their knowledge within social networks. Ingrid Boas, for instance, recently explored how pastoralists in Laikipia use basic phones, smartphones, social media platforms, virtual herding and other combinations of physical and digital strategies.

Maasai pastoralists in northern Tanzania create new social ties through wrong number connections on their phones.

In SPARC’s research project, the varied exchanges (information, products, and care) possible across radio, phone, and social media platforms set the stage for a focused exploration of the nature and extent of social media use in the drylands, how social media might influence information campaigns and product marketing, and how those new livelihood opportunities could be best tailored for pastoralists. We have partnered with Wowzi, which provides a platform building on social capital and the trust of regular social media users to spark conversation about products, services and information. Since its launch in 2018, Wowzi has enrolled over 50,000 influencers running over 15,000 social media campaigns in seven African countries.

The numbers are in: pastoralists are connecting through social media

SPARC research led by Nendo Advisory synthesises key figures—on Internet penetration, mobile network quality, device affordability, gender-based access to mobile phones and the Internet—with qualitative evaluation of audiences and conversations into a snapshot of social media trends in pastoralist Kenya. We have an initial understanding of who is using which social media platforms, in what ways, and hypotheses explaining these patterns. Importantly, we now have a sense of social media’s potential for civic participation, e-commerce and community resilience in the drylands.

Pastoralist use of mobile phones and Internet is growing, but so might the gender gap

Mobile phones have become integral to the lives of many pastoral communities. In Kenya’s arid and semi-arid lands (ASALs), the percentage of households using a mobile phone at least once a year increased from 45 per cent in 2009 to more than 80 per cent in 2015. Similar diffusion rates are observed elsewhere. Broadly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), mobile subscription grows 4.6 per cent per year on average. The Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA) expects SSA to record over 600 million mobile subscribers—approximately half the population—by 2025. The economic potential is significant; in 2018 alone, for instance, mobile technologies and services in SSA generated US$144.1 billion, roughly 9 per cent of the region’s GDP. Even with these gains, SSA’s mobile Internet coverage gap is more than three times the global average.

Mobile phones have become integral to the lives of many pastoral communities.

Major 3G and 4G rollouts in West and East Africa have resulted in a five percentage-point reduction in the coverage gap between 2019 and 2020. More than a quarter (28 per cent) of the population in the region are now using mobile Internet—doubling the usage level in 2014. The coverage gap is amplified in the drylands. In Kenya, for example, there is 63 per cent mobile ownership in the drylands but Communications Authority data reveals that only 3 to 16 per cent of these owners use their mobile devices to access the Internet. Feature phones continue to dominate because of affordability, durability and battery life. Financing plans such as Safaricom’s Lipa Mdogo and second-hand markets are enabling drylands customers to shift to entry-level smartphones. However, with this change, smartphone users in these regions—and digital content and service providers—must navigate the triad identified by Nendo elsewhere: Bundles, Battery, and Bytes. Given their core capability as “reliability professionals”, pastoralists may be uniquely adapted to the flexible improvisation required in rationing bundles, for instance.

2G and 3G tend to underpin the mobile network infrastructure on the continent, and the rise of 4G is unevenly distributed—in Uganda, for example, rural and drylands areas are locked out of the 4G clusters.

The mobile phone’s portability, and the capability for oral communication lends itself well to transhumance. Drawing on recent research, Nendo identifies specific ways pastoralists currently use mobile phones: exploiting information and communication services in herd management to gain information on water resources and forage, weather conditions and veterinary services—researchers have found that a small proportion of pastoralists in Isiolo, Wajir and Marsabit are exploring mAgriculture; virtual herding where “elite pastoralists” use mobile phones to access information on their herds and make payments for labour and inputs, among other uses; obtaining market information by exchanging updates on livestock prices and volumes; contacting medical assistance and veterinary or extension services as well as providing local health workers with information on population structures, pregnancy outcomes and migration patterns; acting as warning systems by exchanging information on hotspots for conflict, such as banditry, or sightings of dangerous animals; pastoralists in East Africa have, for example, used phones to warn each other of sightings of dangerous animals, thus reducing human/animal conflict.

Pastoralists’ use of mobile phones is also contributing to community growth and participation through social connection—keeping in touch with family and relatives (and even making new ties through “wrong number connections”) through audio calls and voice notes; through trading and finance—making payments, and accessing credit; through activism and politics, particularly the use of WhatsApp groups that share videos and voice recordings as well as live-streaming national TV channels on YouTube; and in local and regional planning where phones are used to provide authorities or project planners with information to support evaluation and improvement of programmes or services.

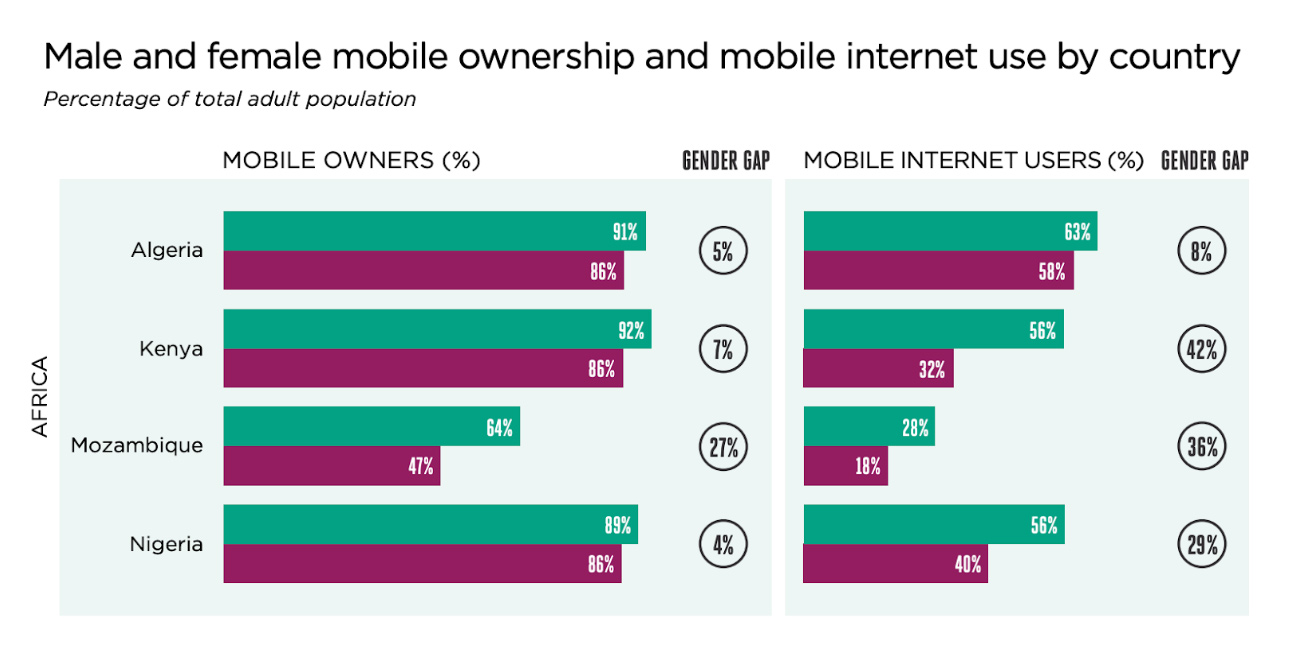

Certainly, variance in infrastructure such as consistent grid electricity and cellular networks constrains the frequency and extent of mobile usage. Importantly, despite growth in mobile phone ownership, gender parity in Internet access lags behind in several countries. As in other regions, a gender gap persists as women have lower access to devices and Internet use. Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic triggered a retraction of some of those gains in technology access for women.

Maasai women in northern Tanzania, however, illustrate the possibilities of redressing the mobile phone gender gap. They are using phones to keep in contact with hired herders, as a tool in organising their home duties, and as a way to collectively advocate for their rights to education, among others. Here, the mobile phone’s radical potential lives on. Regrettably, social media platforms reflect and amplify the gender gap. For example, Facebook is popular in Kenya but 60 per cent of the membership is male, and half the Facebook population is based in the capital city.

What is happening in pastoralist digital communities?

How else are pastoralist communities utilising those precious call minutes and mobile data? Launched in their 2019 The State of Mobile Data report, Nendo’s 5S’s framework remains one of the continent’s reference points in capturing and explaining behaviour around Internet data usage: Search—with Google as Africa’s most visited website and Google’s Android as the #1 smartphone by market share, search is a mainstay of the online experience; Sport—Sports betting has taken on a meteoric rise in the last eight years. Using mobile money (M-Pesa) in particular, this vice has led to millions coming online and participating in deeper ways, consuming sports-related content with football dominating; Social—Facebook is Kenya’s largest social network with over 11 million users. Facebook is only outranked by instant messaging app WhatsApp. Instagram tends to rank high as a leading visual social network alongside newcomer (but fastest-growing) TikTok. Twitter maintains influence but remains mainly used by urbanites; Sex—in many African countries (with almost no exceptions) adult websites rank in the top 10 most visited websites; Stories—YouTube, local blogs/vlogs, mainstream media, and content creators are emerging as a crop of African storytellers and publishers create content and grow audiences.

SPARC’s working hypothesis is that the drylands have a similar consumption breakdown, inflected by connectivity levels. Nendo notes that streaming of local and international music may be a favoured pastime, if the number of drylands creators in YouTube’s “Trending” section is any indication.

Online behaviour can further be understood by analysing the types of people that use the Internet. Nendo’s 5S’s framework explains what happens on the Internet, while the Kantar/TNS framework explains why and how the online users spend their time on the Internet. Functionals are limited by data, Observers have time and data but don’t post. Connectors post often but are limited by megabytes and time. Leaders and Super Leaders create the content.

Also referred to as the “Wikipedia Rule”, the 90-9-1 rule states that 90 per cent of users will be “lurkers” who do not engage (observe but do not contribute, like, retweet, share, or engage). Nine per cent will be contributors who observe and occasionally contribute while 1 per cent are the heavy contributors and creators. In the drylands, like elsewhere, content creators range from influencers with large followings to micro- or nano-influencers across Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. Like citizen journalists and storytellers using community radio in pastoralist regions, these social media users are circumventing any language barriers tied to global platforms by creating content in their own languages. According to Wowzi’s typology, only a small fraction of creators will be “super influencers” and the greatest membership and audience of social media platforms is users with less than 300 followers.

As a corollary to the Wikipedia rule, the engagement rates for large creators tend to be lower as their numbers of lurkers tend to weigh higher and lower the engagement scores of the contributors. Wowzi’s core insight is that audiences find their connections with fewer follower counts (“nano-influencers”) to be more trustworthy content creators than more established celebrity brands. This nano-influencer segment might be an untapped engine of social capital. Since its launch in 2018, Wowzi has enrolled over 50,000 influencers running over 15,000 social media campaigns in seven African countries. It may be cause for celebration, then, that nano-influencers are the largest segment of social media users in the drylands.

Could social listening influence pastoralist futures?

What’s trending on Facebook among the 59,000 users in Garissa, or the 43,000 in Isiolo? The patently false myths of pastoralists as low-tech or anti-tech notwithstanding, the global push for transparency and accountability from Big Tech and social media platforms is justified. After failing to stop the dissemination of paid hate speech in Myanmar, Ethiopia, and around the Kenyan elections, Facebook came under pressure to tackle election disinformation ahead of the Brazilian elections in October 2022. As TIME magazine’s recent exposé Inside Facebook’s African Sweatshop and Quartz Africa’s series on the gig economy show, platform capitalism and digital work—jobtech—is far from utopian. Gig work is subject to the same inequalities in offline or traditional labour markets—whether informally on social media or governed by e-markets like Jumia. Even so, when the Nigerian government bans Twitter, or Ethiopia and Uganda shut down the Internet, their actions reflect a recognition and fear of their digital citizens’ collective power. Certainly, Kenyans on Twitter—#KOT—continue to show the power social media has for connection, group mobilisation and advocacy. In forecasting the livelihood potential of social media, SPARC’s 2021 report, Resilient Generation, offers recommendations on supporting young people’s prospects for decent work in the drylands of East and West Africa.

It may be cause for celebration, then, that nano-influencers are the largest segment of social media users in the drylands.

Imagine activating pastoralist digital communities in marketing dryland-specific services, in intra-pastoralist organising, and regional advocacy. Practical campaigns testing this model could inform how innovation and resilience are calibrated by dryland inhabitants themselves, while challenging technology providers to transform their platforms and offerings to integrate flexibility and inclusion more broadly. To do so well, we require analytical frameworks, specialised analysts and computing power—or, social listening technology. We could use such tools to monitor online conversations and collect publicly available data from different social media networks, highlighting broader demographic information as well as audience sentiment to drive meaningful engagement. Apart from SPARC’s current partnership with Wowzi, we could not identify any other social listening technologies designed for or applied in pastoralist regions.

In the interim, politicians and leaders can use social media to complement their engagements with historically marginalised populations, such as those in northern Kenya. Like Wowzi, more businesses could explore opportunities to acquire new staff and customers in pastoralist regions through similar channels. Global investment is primed to scale such commitments. The United Nations declared 2026—three years from now—the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists. 102 countries and 308 organisations now support the IYRP! 2021 kicked off the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration.

We welcome your suggestions and examples for social media in the drylands. You might start with SPARC’s digital dashboard mapping over 40 innovative solutions designed with and for pastoralists and agro-pastoralists in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASALs) and Fragile and Conflict Affected States (FCAS). In addition to addressing immediate shocks and stresses, we are keen to hear what innovations, including those leveraging social media, could stimulate and sustain economic and other well-being outcomes for pastoral communities over the long-term.

–

SPARC, a programme of Cowater, ODI, the International Livestock Research Institute and Mercy Corps, aims to generate evidence and address knowledge gaps to build the resilience of dryland pastoralists and farmers to the effects of climate change.