There was a time when the root causes of Uganda’s economic failure were so mercurial that one could never quite locate them. The evidence sometimes suggested incompetence; other times corruption; often a combination of the two. Examining the fiscal policy at a granular level reveals the method in the madness: there is now incontrovertible proof that incompetence is an essential part of – and is often allowed to flourish in order to facilitate – grand corruption. We are not talking about small players operating out of cramped government offices but about the country’s top leadership and their foreign and domestic partners.

In an old story, President Mobutu Sese Seko is said to have approached donors for assistance with Zaïre’s out-of-control external debt. By that time, his history of raiding the treasury was widely known and the donors facetiously suggested he lend the government the money they needed out of his personal resources. He is said to have answered, “I can’t trust them to pay me back.” (This is only funny when it is not happening in your own country.)

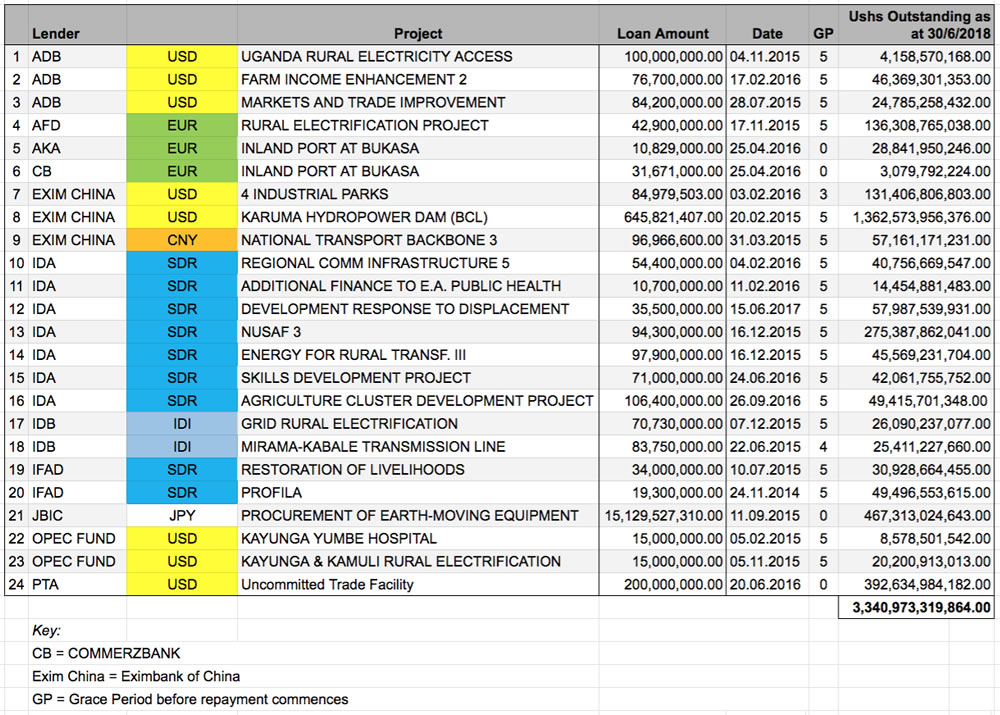

Uganda is in a similar situation. Unsustainable debt is rising in direct proportion to the wealth of the top leaders. When payment of the over UGX 3 trillion balance on over 20 loans (Table 1 below) commences in 2020, the country’s debt-to-revenue ratio will jump from 44% to 65%. In 2015, when Uganda’s debt repayments stood at 38% of GDP, between 26% and 36% of the population was undernourished. Undernourishment has made steady progress, rising by 1% a year between 2006 and 2011 and accelerating to two percentage points plus every year from 2011 (World Bank). Nothing has happened since 2016 to ensure undernourishment does not increase; in fact, it rose from 39% in 2015 to 41% in 2016. In contrast, world undernourishment fell 14 percentage points over the same period and is on a downward trend except for a short rise in 2015-2016.

Despite trends in the increasingly unsustainable loan portfolio, on the one hand, and erratic public administration on the other, the IMF has assessed Uganda as a low risk for external debt distress. It says the risk was not increased by significant risks stemming from domestic public and/or private external debt.

As a justification for further borrowing, President Yoweri Museveni and Ministry of Finance officials claim that the debt-to -GDP ratio is within the historically safe limit of under 50%. The Auditor General has been of the contrary view, saying debt levels are “unfavourable when debt payment is compared to national revenue collected which is the highest in the region at 54%.”

That argument has been overtaken by events. Current International Monetary Fund (IMF) projections show that debt-to-GDP will hit 49.5% in 2021. Furthermore, it is guaranteed to deteriorate as the outstanding balances on the loans will increase as the shilling continues to slide against the dollar and as further non-concessional (high-interest) loans are taken in the domestic market, such as the $104 million to be spent on security cameras and loans for ad hoc investments like the revival of Uganda Airlines at $388 million.

Despite trends in the increasingly unsustainable loan portfolio, on the one hand, and erratic public administration on the other, the IMF has assessed Uganda as a low risk for external debt distress. It says the risk was not increased by significant risks stemming from domestic public and/or private external debt. (Debt Sustainability Analysis).

They went on to claim, “Uganda’s economic performance remains strong, but has moderated in recent years.” Further, “Government finances remain on a sound footing…” The only suggestion in the Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) that all may not be well (inserted no doubt as a basis for claims to due diligence to be made after the economy crashes) was “… though expenditure composition can be of concern.” Expenditure composition includes items not part of the National Development Plan e.g. a national airline and a network of security cameras. In the same year, the Auditor General pointed out a serious barrier to attaining development targets: loans were performing poorly. He could not have been clearer when he warned that interest payments were becoming unsustainable (Auditor General 2016 p. 14).

“Several loans appeared to be performing poorly, with some nearing expiry; while others reached the closing date without fully disbursing. As at 30th June 2016, committed but un-disbursed debt stood at UGX 18.1 trillion [approximately US$5 billion]. Such low levels of performance undermine the attainment of planned development targets and render commitment charges of UGX20.9 billion (US$5.9 million) paid in respect of undisbursed funds nugatory [i.e. wasteful or of no value] (Auditor General 2016, p.72).” In other words, borrowed funds were not being put to use.

The problem has persisted in 2017 and 2018. This gives the lie to the IMF’s DSA 2016 finding that Uganda is scaling up infrastructure for future economic growth. The IMF admitted a risk to growth goals would be “failure to realize the envisaged growth dividend from the increased investment is a key risk”. What they did not mention was that the contingency had already materialised. A 2015 special audit of the Uganda Support to Municipal Structure Development (USMID) project (financed with a $150 million loan) showed under-utilisation of loan funds accompanied by incomplete projects requiring funds. The risk is that idle balances will eventually be diverted, as has happened in Hoima Municipal Council.

We are not far from a full admission that Uganda is in debt distress although there are still the persistent and irrelevant claims of on-target economic growth (of 6.3%). Irrelevant because it was during the past periods of alleged high economic growth that universal primary education was degraded to the point where the drop-out rate was 60%.

The current situation is that 95% of the UGX100 billion disbursed under USMID for municipal development and capacity building grants remains idle (Auditor General 2018, p. 5). Understaffing in specialised technical areas is one reason municipalities are unable to utilise infrastructural development loans. (Understaffing is a result of a cap on recruitment enforced by the IMF.) Yet for the past three years the Treasury has only been able to release UGX417 billion of the UGX800 billion required annually to maintain the feeder roads so crucial to farmers (Auditor General 2017, p. 33).

Uganda’s fiscal policy is ‘a moving target’

In 2019 the IMF is leaning towards the Auditor General’s point of view. They now say that rising interest payments reduce resources available for education and health (human development). Their latest assessment states, “The current ratio of interest payments to revenue is comparable to what countries with high risk or in debt distress typically face.”

We are not far from a full admission that Uganda is in debt distress although there are still the persistent and irrelevant claims of on-target economic growth (of 6.3%). Irrelevant because it was during the past periods of alleged high economic growth that universal primary education was degraded to the point where the drop-out rate was 60%. During high economic growth, inequality, and especially rural-urban equality, deepened. High economic growth preceded the current phase of social unrest. According to the IMF, “In each of the last three macroeconomic assessments of Uganda, the projected debt path was revised upwards. Having a clear direction for fiscal policy would help budget planning and execution.”

Nevertheless, the IMF continues to claim that the risk of debt distress remains low, provided domestic revenue can be mobilised. The set target under the National Development Plan II and medium-term Sustainable National Development Plan is to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio from 14% to 16% by 2019/20. If this cannot be achieved through job creation, it can only translate into more taxes and austerity measures.

The question arises: With Uganda’s history of poor public administration and disastrous debt management, corruption, and increasing civil unrest and repression, what was the basis of the IMF’s optimism? The organisation has a permanent office in the Ministry of Finance and its headquarters sends multiple missions every year to monitor economic progress. To solve Uganda’s perennial economic distress, citizens must first understand the IMF’s mission in Uganda.

In any event, the grace period on over 20 loans expires in 2020 and debt is now of concern. On top of expenditure on projects in the Public Investment Plan, there is significant expenditure arising from unplanned projects, such as the revival of Uganda Airlines, requiring $380 million. Lubowa International Hospital, initially planned as a public-private partnership with Finasi (a commodities trader) it eventually became a contract for Finasi to build and operate a hospital funded 100% by the Government of Uganda.

Incompetence in industrialisation and job creation

A recent round of commissioning of factories and other infrastructure has proven that infrastructural development is a chimera. The Isimba Dam launched in March may generate but does not transmit power. Together with Karuma, to be launched later in the year, it cannot do so without further expenditure of $3.5 billion to extend the grid. The Nile Bridge had to undergo major remedial work owing to poor construction only days after commissioning. The president’s electioneering took in at least one factory many years old and employing a miniscule number of Ugandans. Nile Agro Industries Ltd has been producing soap, wheat flour, cooking oil, bottled water, lint bales, and fortification and industrial plastics since 1999. Yet it was commissioned and “launched” on 7th May 2019.

The Soroti Fruit Factory was founded in 2014 and funded by the government and a grant of $7.4 million from Korea. Last year’s audit listed the factory as un-operational after accumulated public investment of UGX 13,353,129,943. The factory was commissioned by the President on 13th April 2019. It was reportedly closed on 10th May owing to a lack of operating capital for fruit from about 1,000 farmers and salaries for the 123 Ugandan employees. The government’s investment arm, Uganda Development Corporation, has been advised annually for at least three years by the Auditor General against making investments without feasibility studies but in Soroti it was the usual case of ignoring professional advice and pandering to the president’s whims.

“The corporation incurred expenditure amounting to Shs.9,000,026,869 during the year in undertaking industrial development investments in the areas of fruits in Luwero, Soroti and processing in Kabale and Kisoro. However, the Corporation did not undertake investment strategic studies assessment prior to undertaking investments for purposes of assessing the marketability and commercial viability of the final products processed from fruits like mangoes, oranges and tea plantations. The investment may not achieve anticipated results.” (my emphasis) (Auditor General 2016 p. 519)

Apart from Soroti Fruit Factory, other warnings have related to Kampala Industrial and Business Park, Namanve, where UGX 1,000,000,000 for a feasibility study was diverted. Over UGX 131 billion is outstanding on loans for four industrial parks, including Namanve. Although National Information Technology Authority-Uganda (NITA-U) carried out a feasibility study for Commercialisation of the National Data Transmission Backbone Infrastructure (NBI) and E-government Infrastructure (EGI), it did not factor in the costs of its maintenance. “As a result, it was difficult to assess the economic sense of the project as Management lacked sufficient benchmark to assess the bid proposals on contract aspects such as the cost of maintaining the NBI, revenue sharing ratios and price of internet services.” (Auditor General, 2017, p. 53)

It is indicative of the general problem pointed out by the Auditor General, who concluded that ignoring planning procedures is a major weakness within the Ministry of Finance “and presents a risk of funding projects which are not feasible and are not aligned to the National Development Plan (NDP).”

New projects are required to undergo four stages prior to being included in the Public Investment Plan (PIP) and commencement: (i) Prepare a project concept in line with NDP, (ii) Prepare a Project Profile demonstrating key results, (iii) Undertake a pre-feasibility study, and (iv) Conduct a feasibility study. But the auditor found that “some projects obtained project codes and admission into the PIP without proper project vetting as stated in without vetting them”.

It is indicative of the general problem pointed out by the Auditor General, who concluded that ignoring planning procedures is a major weakness within the Ministry of Finance “and presents a risk of funding projects which are not feasible and are not aligned to the National Development Plan (NDP).” (Auditor General, 2017, p. 15)

Foreign direct investment

To attract foreign direct investment (FDI), many countries around the world privatised their telecommunications sectors – some voluntarily and others, like Uganda, under an IMF structural adjustment programme. In the UK in the 1990s, public awareness-raising of the move involved repeated assurances that after unbundling postal and telecoms services, 51% of shares in British Telecom would be sold to the private sector but with the proviso that 34.3% would be sold to the general public. Furthermore, in the interests of promoting share ownership, the shares were priced at £130, a price considered below their value.

Kenya sold its telecoms sector, reserving 60% of the shares for the Kenyan state, of which 30% were later sold directly to the public. The new entity, Safaricom, went on to become the most profitable private company in the East African region.

Cross the border into Uganda where income from the lucrative telecoms sector is enjoyed only by a narrow oligarchy. Although the government was to retain 49% of the shares in Uganda Telecom, it currently holds only 31%. Much has been written about how MTN went from being the second national operator to a virtual monopoly and regulator of the sector.

MTN is the biggest player, with 54% of the telecoms market. Only 5% of MTN shares are Ugandan-owned, (the Ugandan being an individual with board membership in at least two privatised entities, including the defunct Rift Valley Railway.) It is only in the past few months that the president began to press MTN to make some of its shares available to the public.

Uganda Telecom, the entity that was supposed to retain residual rights in the sector, was only created after Celtel and MTN (the first and second national operators) had been running for a while. This has meant that MTN has the technology to permit or bar new indigenous competitors from the market, which reportedly it does. Indigenous Ugandan start-up Ezeemoney, a mobile money platform designed to allow banking over different platforms (i.e. between MTN, Africell and other service providers), was awarded over two billion shillings in a suit against MTN for refusing to provide them with access to the network.

Tax evasion and illicit transfers

Returning to the objectives of privatisation and incentivising foreign direct investment, greater efficiency and cash inflows may have been achieved but the benefits have been annihilated by illicit outflows mainly facilitated through tax evasion.

Another 13 foreign investors have been found to have used a lacuna in the law to avoid taxes for years, a fact the IMF was in a position to know. Thirteen of the investors owe UGX 353.5 billion. Some have been beneficiaries of FDI incentives, another has been operating in Uganda since 1969 (and therefore not in need of incentives). One is in possession of the infrastructure that is the privatised Nytil textile manufacturing plant (founded in 1954). A fourteenth is a joint venture once touted as the only manufacturer of ARVs in Africa. It was founded to supply ARVs for domestic consumption and export to Burundi, the DRC, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Cameroon, Comoros, Namibia and Zambia. The majority shareholding is foreign-owned; the three major Ugandan shareholders own less than 10% of the shares and 18% were sold on the stock exchange in 2018. It turns out that the company may really be in the business of acquiring government tenders for a parent company in India.

In response to the discovery that opportunities to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio are being systemically undermined by tax evasion by investors, the Ministry of Finance this month tabled a proposal in Parliament to give the offenders a waiver of taxes owed on the basis that it would be unwise to drive FDI away by collecting the arrears.

Returning to the Mobutu story, it is not just African despots who have sufficient illicit funds to make a significant dent in their countries’ public debt; the taxes owed by foreign investors could clear it. MTN’s tax arrears (of UGX 2.8 trillion as extrapolated from data recovered during litigation) could clear 73.6% of the current UGX 3.4 trillion outstanding balance on the loans which Uganda will begin to repay in 2020.