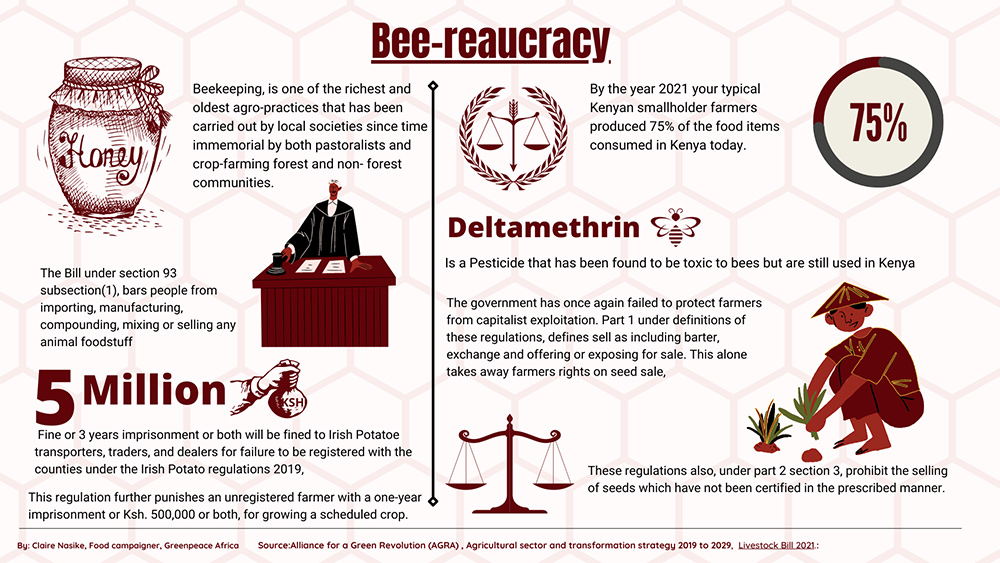

By 2021 your typical Kenyan smallholder farmer was producing 75 per cent of the foods consumed in the country. Yet the draconian laws imposed on the agriculture sector by the government have been facilitating their exploitation by private sector actors including multinational corporations. This is in total contradiction with President Uhuru Kenyatta’s move to include food security in his Big Four Agenda and begs the question of how the country can achieve food security when farmers are discouraged from producing food by these punitive laws.

Recently, there was an uproar on social media regarding the Livestock Bill 2021. The point of contention in the yet to be gazetted Bill is a clause that bars Kenyan farmers from keeping bees for commercial purposes unless they are registered under the Apiary Act. The government, through the Permanent Secretary for Livestock Mr Harry Kimutai, tried to justify this by saying that the aim of registering beekeepers is to commercialise beekeeping instead of it being a traditional practice.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial and it has been part of the subsistence economy of smallholder farmers who pass on this rich knowledge and expertise from generation to generation.

Bee-reaucracy

In its current form, the Livestock Bill 2021 will drive smallholder beekeepers out of honey production and pave the way for multinational corporations under the guise of regulating the sector. It is no different from the Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019-2029 that seeks to move farmers out of farming into “more productive jobs”, opening the door for their exploitation and impoverishment by agro-capitalists.

In a recent media interview, Mr Kimutai said that Kenyan honey is contaminated with pesticide residues. But if the government is indeed concerned about improving honey production, it should start by banning the use of toxic pesticides that are detrimental to bees and contaminate the quality of honey. Pesticides such as Deltamethrin have been found to be toxic to bees yet they are still used in Kenya.

Local pastoralist, agrarian and forest-dwelling communities have practiced beekeeping since time immemorial.

Section 93 subsection(1) of the Bill bars the importation, manufacturing, compounding, mixing or selling of any animal foodstuff other than a product that the authority may by order declare to be an approved animal product. This offence attracts a fine of KSh500,000 or imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months, or both.

Smallholder livestock farmers in Kenya have been growing “napier grass” to feed their cows and for sale to other farmers. Do these new regulations mean that they shall be committing an offence by growing their own feed and selling it within their localities?

Another punitive regulation is the Crops (Irish Potato) Regulations 2019, that requires transporters, traders and dealers to be registered with their counties, failure to which they face up to KSh5 million in fines, three years imprisonment, or both. This regulation also punishes an unregistered farmer with a one-year imprisonment or KSh500,000 or both, for growing a scheduled crop. It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Through the Seed and Plant Varieties Act 2012, the government once again fails to protect farmers from capitalist exploitation. Part 1 of the Act defines selling as including barter, exchange and offering or exposing for a product for sale, taking away a farmer’s right to sell, share and exchange seed, a right that is recognised in the constitution.

Part 2 section 3 of the Act prohibits the sale of uncertified seed. The good old practice of selling and sharing seeds is further criminalised in section 7(5) which requires only seed appearing in the Variety Index or the National Variety List to be sold. This limits farmers from selling their varieties which they have been sharing, exchanging and selling for generations. Moreover, this automatically means that farmers selling their seed varieties are committing an offence if such varieties are not listed in the index.

Further, section 18 part 4 of this act allows for the discovery of a plant variety whether growing in the wild or occurring as a genetic variant, whether artificially induced or not. This section allows for the discovery of farmers’ indigenous seeds by multinational corporations keen to patent them for profit.

It is no coincidence that capitalist-funded organisations like Alliance for a Green Revolution (AGRA) applaud the Irish Potato regulations as a new dawn for Kenyan farmers.

The implication here is that since farmers’ seed varieties are not registered or owned by anyone, anybody can obtain the seeds of any crop variety, apply for their registration and claim their “discovery”. Farmers who have been conserving and reusing the “discovered” seeds will then lose the right to continue doing so and they will be required to pay royalties to the new “owners” of these seeds.

This act contravenes certain provisions of the constitution, in particular Article 11 (3) (b) of the Kenya Constitution 2010 which states that parliament shall enact legislation to recognise and protect the ownership of indigenous seeds and plant varieties, their genetic and diverse characteristics and their use by the communities of Kenya.

Foreign laws

The parliament has forfeited its obligation to enact laws that protect and enhance our intellectual property rights over the indigenous knowledge of the biodiversity and the genetic resources of Kenyan communities as mandated by Article 69 (1) (a) of the Kenyan constitution. It has allowed external actors to pirate local resources and trample indigenous rights.

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons. The government is in cahoots with large corporations determined to kill the smallholder farmers’ sources of livelihood while singing about food security being part of the Big Four Agenda.

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

What sense does it make to frustrate smallholder farmers who grow 75 per cent of our food to serve the interests of imperialist multinational corporations keen on holding our farmers at ransom through abhorrent fines?

Patenting indigenous seeds, barring farmers from keeping bees, and regulating the growing and selling of animal feed and potatoes is theft of the commons.

It is time to reclaim and protect the commons that our communities have for a very long time thrived on. In her book Reclaiming the commons Dr Vandana Shiva points out that indigenous communities, including farmers, co-create and co-evolve biodiversity with nature, practises that have seen them overcome ecological challenges for generations. Our policies, plans and laws need to protect these practices for posterity.

Our parliamentarians should endeavour to defend our biodiversity, indigenous cultures and national systems – reclaiming the commons. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce food using indigenous seeds that are readily available and that they can be share amongst themselves. We need policies that will allow farmers to produce safer and more healthy food in an environmentally safe way, not punitive policies designed to eliminate farmers and have our food system controlled by corporations out to make profits at the expense of our health and our environment.