Somi is running late.

It is the Sunday morning after the February 2019 presidential elections that saw President Muhammadu Buhari returned to office and Lagos has endured a wet weekend. The roads have become flooded with rainwater escaping out of blocked drains, carrying with it styrofoam, plastic, non-recyclable waste and reusable debris. Traffic is what results. Traffic of short tempers and selfish driving, traffic of potholes and murky water, traffic that validates Fela’s claim in his tune Go Slow, traffic that traps Somi in an Uber taxi from where she sends a text message, “I am running late.”

I find her courtesy rather unusual. My experience of artistes in Nigeria is that being late for appointments is typical and not showing up is the rule. Somi apologises effusively when she finally arrives, hurriedly walking in, looking gorgeous in her flowing blue Adire gown.

“You just walk around and everyone is in their best and they just seem to try and find courage to face the next week. I introduce my song, with words about a woman who dared to dream, despite having a difficult life”, Somi says in a restaurant full of people in their Sunday best.

We are at the Cactus Restaurant on Victoria Island, an upscale diner popular for its Sunday brunch. The clientele is mostly elaborately dressed Christians just from church; middle-aged, bespectacled, brocade-wearing men sporting Yoruba caps and holding teenage daughters by the hand, mothers in George or Velvet or Ankara and elaborately styled headgear, strutting with the kind of confidence associated with ownership, bespectacled teenage sons, gangly and pimply, walking in their wake.

Somi lives in New York. She is visiting Lagos for pre-production meetings for her seventh album, recording rough demos and workshopping ideas with Cobhams Asuquo, the producer with whom she made her iconic fourth album.

Her seventh album is yet to be titled, but she says it is in conversation with her stage play, Dreaming Zenzile, which is about the life, the times and the music of the late South African singer and activist, Miriam Makeba.

“My new album is in conversation with my play,” Somi says as she flips the menu, considering breakfast options. She makes her order and asks for extra avocados on the side.

Somi is no stranger to Cactus. She is also no stranger to Lagos. She had first been invited to Lagos in 2010 by the organisers of the Lagos Jazz Festival, but they were tentative about their dates—their major obstacle being the upcoming 50th anniversary of Nigeria’s Independence celebrations.

By sheer happenstance, Somi was visiting friends in Lagos when the organisers of the Lagos Jazz Festival finally settled on dates, but the timing was still off. Lagos would be deprived of the magic of Somi and her five-man band but, providentially, Somi would comb the city on her own terms, flitting between working class and upscale areas, the Mainland and the Island, and falling in love with Yaba, an iconic part of the megacity.

Another opportunity to visit Lagos came soon enough; a seven-week International Art Residency at Kwara State University in Ilorin, in collaboration with New York University. Somi had been recommended by Professor Awam Amkpa of the Tisch School of the Arts, New York University, who had remembered how fond she was of Lagos.

“I came back to teach in Ilorin for seven weeks since that was all the time I had available. I remember looking up Ilorin and it was like a million, two million people . . . I love the idea of going to an African city that is not really like the centre,” Somi reminisces. She planned on spending three days a week in Ilorin and four in Lagos. To her dismay, her teaching at Ilorin was sabotaged by incessant union strikes.

“They kept going on strike and I taught once a week and I was to teach there for seven weeks. So I felt like I didn‘t get to spend time with the students as we all anticipated but it was still lovely. And you know at some point after much thinking, I decided to stay.”

Somi stayed in Nigeria for 18 months. She wrote, workshopped and recorded the songs that would become her fourth album, The Lagos Music Salon.

I experienced Somi’s The Lagos Music Salon (TLMS) on Ethiopian Airlines’ inflight entertainment in 2015. Cruising many miles above sea level from Lagos to Addis Ababa, I happened upon this album named after the city I call home, Lagos.

Lagos is a conundrum of a city. Lagos is where the dreams of most Nigerians berth, optimistic that they shall come to pass. But like most cities, Lagos also engenders disappointment in the long run. Dreams may take their time to fruition, and so the citizens of Lagos are best classified thus: those who have made it and those who are in the process of making it.

The cover art on the TLMS album is of an elegant black woman wearing an Ankara dress leaning against shabby wooden panelling. The art already speaks to the Lagos characteristic of yoking style to squalor; and so I listened.

Cruising many miles above sea level from Lagos to Addis Ababa, I happened upon this album named after the city I call home, Lagos

Every song on TLMS keys into the Lagos experience. Eighteen songs lasting a bit beyond an hour. The impression is an eternal one. One is in awe of the possibilities of powerful vocal cords and intricately curated music exploring the boundless complexity of a city that over twenty million people call home.

TLMS is a contemporary album in conversation about the city, but within the ethos of the city’s past as well as her musical traditions. Following a brisk introduction, the album pays homage to juju music—the soundtrack of the city through the 70s—with the vibrant up-tempo love song Love Juju #1 teasingly conflating the existing misconception about the nomenclature of that variant of palm-wine music. Juju here could mean the music whose name is possibly derived from the onomatopoeic Yoruba verb “to throw”, or an intense romantic affection that could be the consequence of hypnosis. Somi plays both sides with talking drums and the steel pedal guitar.

Every song on the album leans into jazz, but this is jazz music out of its comfort zone, in constant collision with newer interpretations and African languages. Somi is so fascinated by the way life happens in Lagos and her panoramic gaze eschews class, sex, gender and occupation; she is inexhaustibly preoccupied with what it means to be every kind of human in Lagos.

The art already speaks to the Lagos characteristic of yoking style to squalor; and so I listened

Listen to Somi’s Brown Round Things and you are thrown into the devastating beauty of Lagos nights. Accompanied by Ambrose Akinmusire’s piquant trumpet notes, the song knifes through the night and beautifies the nocturnal mundanity of the sex work that animates certain aspects of the city. Admiralty Way, Lekki. Sanusi Fafunwa, Victoria Island. And Allen Avenue, the Mecca of the Lagos Red Light District.

The album’s interludes and skits are byte-sized aural delights of certain sounds characteristic of Lagos. Yet, the most accomplished of these songlets is Somi’s visitation of Nelly Uchendu’s Love Nwantintin which enjoys the gospel feel of the acapella group In His Image—a sultry tribute to Lagos by way of the River Niger.

The victory of Somi’s album lies in how it curates Lagos’ sounds and kinetics in a manner that is both recognisable and satisfactory. Four years since its release, this album is still the most extensive jazz album detailing the Lagos experience and the most original interpretation of the city since Fela Anikulapo-Kuti.

Google Somi and you are likely to fall upon another Somi, a Korean-Canadian singer and songwriter who broke out through Produce 101, an M-Net survival reality show.

This Somi’s full name is Laura Kabasomi Kakoma whom Wikipedia describes as an “American singer, songwriter and actor of Rwandan and Ugandan heritage”.

Every song on the album leans into jazz, but this is jazz music out of its comfort zone, in constant collision with newer interpretations and African languages

Somi was born in Illinois to a Rwandan academic father and a Ugandan mother. Her family would relocate to Zambia when she was aged three. In the late 80s, her father took up a professorship at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where she spent the rest of her childhood. Somi studied Anthropology and African Studies at the University of Illinois and has a postgraduate degree in Performance Studies from the Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

“Writing was always a private art for me as a child and I‘ve always been a writer of some sort, but it is private, more like catharsis”, Somi says, adding that, “Singing too was a private thing. Like a lot of people, I used to sing as a child and then when my family and I moved to the States, I experienced culture shock and racism. I had an experience with a teacher who was so hostile to me and she shut me up when I was to present a piece I had won an award for and that kind of affected me . . . She was like ‘are you reading or not, just know no one even cares’ . . . I couldn’t sing publicly. Which for me is another reason I decided to play the cello, as I just needed an outlet that didn‘t involve me singing.”

In 2003, Somi released her first album in New York called Eternal Motive, an 11-track album with a monochrome portrait of Somi on the cover. The internet has all but forgotten these first steps but a review of a later work describes it as “electric soul jazz”, a nod at Somi’s love for genre-blending and bending.

Four years later, she independently released Red Soil in My Eyes. Jeff Tamarkin of the All Music Review glowingly remarks, Red Soil in My Eyes is all elegance and awe, and attempting to reduce Somi’s pan-globalism and command of her artistic environment to a single genre or purpose would be a fruitless endeavour. She skates easily between worlds, touching on both smooth and raucous neo-soul, nuanced jazz expression and more than a dollop of East African tradition until something else altogether emerges.”

Ingele, a Swahili song that was a finalist in the world music category of the John Lennon Songwriting Contest, is a moving delight that touches the core of anyone who knows that music is indeed the undertow of the soul. But Somi did not set out to become a Jazz singer: “I wasn‘t setting out to be a jazz singer. I just wanted to be a songwriter and poet. I’ll say I am very inspired by jazz regardless”. Perhaps Somi meant that she had a crush on Jazz and once the inspiration came, it was impossible to resist.

After the release of Red Soil in My Eyes, Somi’s father fell ill and was diagnosed with cancer.

“For me, it put my work on hold and I had to travel to my parent‘s home in Illinois to have time off. It was really a hard time for me at that point and writing the album.”

The songs she wrote through this dark period would become If The Rain Comes First, her third studio album released by Obliqsound at about the time her father passed away.

“It‘s actually an album about how we perceive the challenges in our lives, and in the West, the rain is seen as a negative thing. Where we are from, my mother always talked about how the rain was a blessing.”

The eponymous song achieves an auditory equivalent of petrichor, the sweet smell that comes with the rainfall that Somi sings about. And beyond the varying perceptions of what rain seems to signify, If The Rain Comes First feels like a rite of passage, a washing away, if you will, of pain and grief. This quality spreads throughout the meditative album which also features South African jazz vocalist, trumpeter and flugelhorn player, Hugh Masekela—fondly called Uncle Hugh by Somi—on the hypnotic Enganjyani, which means “most beloved” in Rutooro, Somi’s mother’s language.

All About Jazz qualifies the achievement of her third album thus: “With If the Rains Come First, Somi’s songwriting has taken on a new sophistication and depth. Surrounded by a cast of virtuosic collaborators who understand precisely where she’s going and how to get there, Somi burrows deeply into her words and ultimately something transcendent emerges.”

Somi returned to teach at Kwara State University, Nigeria, before the release of her fourth album, a live album titled Somi Live at Jazz Standard. A 10-track compilation of her songs plus covers of Abbey Lincoln’s Should’ve Been and Bob Marley’s Waiting in Vain, Somi’s live album was recorded over two days at New York City’s Jazz Standard.

“Raw at Jazz Standard might have been a better title, since the hour-long performance so vibrantly captures the unfiltered, unvarnished Somi freed from studio wizardry,” writes Christopher Loudon. Eight years after its release, that experience of being transposed into the past, into the presence of that emotive music stirred by pitch-perfect instrumentation and the majesty of Somi’s vocals and East African languages still happens.

“I actually didn‘t come to Lagos to write a new album, I was actually trying to work on another album”, says Somi. Trust Lagos to wrestle any competition out of your mind. Lagos returned Somi to a place of poetry and not just the final visual poem, Shine Your Eye, that closes The Lagos Music Salon album; a good number of the songs that made the album began their journeys as poems.

On the evening of Sunday June 3, 2012, Flight 992, a McDonnell Douglas MD-83 aircraft belonging to Dana Air and carrying 153 souls from Abuja to Lagos, crashed into buildings in Lagos while attempting an emergency landing. All the passengers and crew on the aircraft and six people on the ground perished.

Somi wrote a poem that became Last Song, for a woman she had fleetingly encountered at a jazz festival a week before the plane crash.

“I met this young lady, we became friends, and I got to know she also just moved back, as a single woman in Lagos . . . I kept thinking about her and sadly we didn‘t exchange numbers . . . So on that Sunday, I was hanging out with some friends when one of them got news that she was among the people that died in the plane crash.”

Last Song is Somi’s tribute to an acquaintance she wished she had known better. It is a poignant re-imagination of how fleeting moments could pass innocuously into the void, how existence is a transient thing, how goodbyes could be ephemeral or eternal.

Somi’s vision often imagines a singular person as opposed to a herd of people. But once she has achieved that emotional resonance with one person, the bigger picture becomes easier to populate.

“After I lost my dad and I didn’t feel understood by the people around me, I decided to take a break and I chose Lagos . . . I had a lot of friends in Lagos from Nigerian friends abroad.”

From around 2010 a lot of Nigerians in the diaspora had returned on account of the prospects of the booming economy. While in Lagos, Somi went around with a digital recorder documenting everything—conversations, traffic sounds, protests and even her own laughter.

Lagos returned Somi to a place of poetry and not just the final visual poem, Shine Your Eye, that closes The Lagos Music Salon album; a good number of the songs that made the album began their journeys as poems

When she realised that a body of work was in the offing, she began to workshop the new material. Azu Nwagbogu, the founder of African Artists Foundation, then located at Raymond Njoku, Ikoyi, graciously provided the space where Somi began to do a monthly series, showcasing songs with a band strung together by Cobhams Asuquo. A good number of those songs found their way into The Lagos Music Salon.

Somi’s sixth album, Petite Afrique, is to Harlem, New York, what The Lagos Music Salon is to Lagos.

Harlem, a historic place, populated by Africans and African-Americans alike, becomes a field for a sonic survey. Somi, the vocalist, anthropologist and virtuoso performer hits closer to home this time, even if the scope of her theme has grown wider.

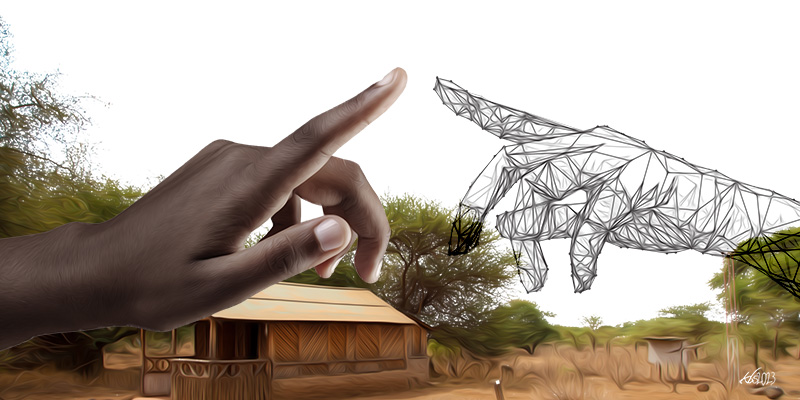

Petite Afrique means “Little Africa” and it is a tribute to a cohort of African immigrants, mostly from Senegal, who reside on New York’s 116th Street. Much as it is about migrants, it is also about the implicit and explicit tension between Africans and African-Americans as is manifest in the kind of conversations they have with each other. The myriad of issues that populate these discussions include xenophobia, islamophobia as well as gentrification—but Somi’s powers shine through in how her message melds seamlessly into the music.

Speaking about how the album came about, Somi says, “It started in Harlem, I think, after The Lagos Music Salon. I lived in Harlem for about ten years . . . Then there was this friction between Africans and African-Americans, and the whole idea of gentrification and the need for unity between these two. So naturally for me, I felt a need to connect with the people of Harlem, having stayed there for a while, so Petite Afrique was my own way of giving back to Harlem . . .”

What Somi achieves in fifty-two minutes and fourteen songs is a triumphant exploration of the black experience. Little wonder then that Petite Afrique received the Outstanding Jazz Album award at the 49th National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Image Awards.

Somi’s career has gone way past her brief stay in Lagos but the city will remain a critical reference point in her career. The Lagos Music Salon changed her career and Lagos will always remain home to her.

As she says, “I love New York, but the thing in Lagos is, if you can make it in Lagos, you can make it anywhere, the city is hard, but when you show up for the city, the city shows up for you.”