History occasionally accelerates with unexpected speed as its slow, subterranean motions suddenly erupt into surges of change, sparked by an event whose ordinariness suddenly acquires an extraordinary potency out of a unique confluence of forces. The triggers of course vary, but there is a particular poignancy that comes with the incendiary intimacy of individual murders. Such killings strike a powerful emotional and cognitive chord in the human imagination in a way that mass murders may not, as their sheer scale congeals into mind-numbing abstractions.

The public execution of George Floyd, with its casual performance of suffocating and snuffing life out of the black body became a frightful spectral presence in the minds of tens of millions of people in the United States and around the world. It captured with terrifying clarity the utter depravity and degradation of a black life that validated the humanistic and historic demands of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The spontaneous demonstrations that erupted across every state and in hundreds of cities and towns in the United States — including some with small black populations and even among those infamous for harbouring white supremacy movements and militias — quickly turned into the nation’s largest and most widespread protest movement against systemic racism since the 1960s, and some claim in American history. It brought both the country and the shambolic Trump presidency to an inflection point.

The uprising over Floyd’s murder derived its fiery multiracial and multigenerational rage from the coronavirus pandemic that disproportionately devastated the lives and livelihoods of black and poor people. It tapped into the surplus time and energies of people seeking release from the isolating suffocations of anti-COVID-19 lockdowns. It also benefitted from the inept and provocative responses of racist politicians and police forces. Further, it was catalysed by the persistent struggles of longstanding activists and social movements.

Assassinations as Historical Inflections

Assassinations have served to trigger major events throughout history. Think of the assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo. This event helped ignite World War I by prying open long-simmering nationalist and imperialist rivalries in Europe. The conflicts were engendered by, and coalesced around, rival alliances that catapulted the world into an unprecedented conflagration.

Think of the brutal lynching of 14 year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi on 28 August 1955 for allegedly whistling at a white woman. The photographs of his mutilated body served to galvanise the American civil rights movement by inflaming age-old grievances and agitation against systemic racism and white supremacy, and the country’s North-South divide, overlaid by the global reverberations of Cold War superpower rivalries and decolonisation struggles in Africa and Asia.

Think of the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, a young street vendor, on 17 December 2010, in protest against state repression and economic distress for young people. It provoked the Tunisian Revolution and the Arab Spring against the autocratic and corrupt ruling coalitions in North Africa, other parts of Africa, Asia and South America, adding fuel to the democratic wave unleashed by the end of the Cold War. Elsewhere in North America and Europe the Arab Spring inspired the Occupy movement.

However, the Arab Spring soon turned into the Arab Winter, pushed back by counter-revolutions comprising resurgent Islamism, the reinstatement of military rule in Egypt, descent into autocracy in Turkey, and ferocious civil wars in Libya, Syria, and Yemen. As for the victories of the civil rights movement in the US in the 1960s, they remained limited and provoked a racist backlash. The Republican Party embarked on the “Southern Strategy” of courting white racists, and systemic racism and white supremacy were propped up with new structural and ideological scaffolding. For its part, World War I led to the consolidation of colonialism in Africa and Asia, reaped the whirlwinds of fascism and Stalinism in Europe, and unleashed the spectre of economic devastation that culminated in the Great Depression.

In short, revolutionary moments generate complex and contradictory futures in which progress is often checkmated by reversals, underscoring the fact that history is a dialectical process. The racist backlash against Obama that led to Trump’s election seems to have succeeded in creating an anti-racist backlash.

The Floyd moment in which the Black Lives Matter movement is gaining traction in the US and around the world will not be an exception. Progress will be made in chipping away at some of the practices, symbols, and performances of anti-black racism, but the fundamental structures of white supremacy are likely to survive and mutate.

In the Shadows of 1968

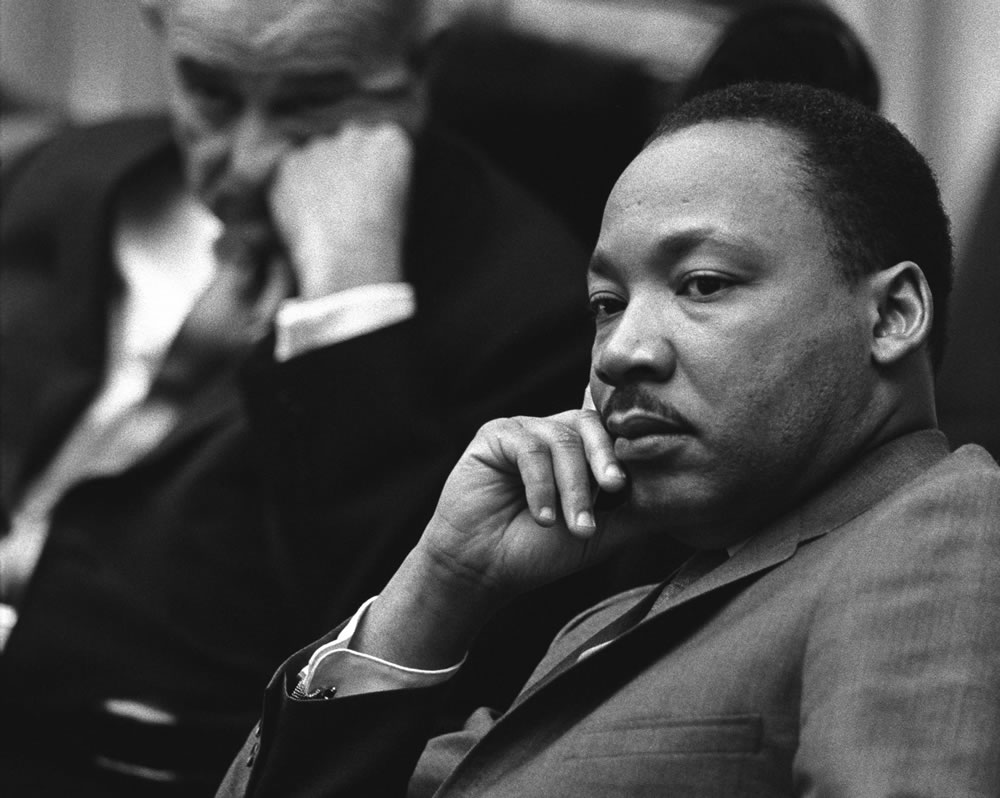

The American uprising of 2020 shares some parallels and connections to the uprising of 1968 following the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King. The script of 1968 remains — notwithstanding some progress — in so far as the protests sprang from the deep well of institutionalised racism, economic inequality, social despair, political disenfranchisement, and the dehumanising terrors of police brutality and constant denigration of blackness in the national imaginary.

The road to 2020 was paved with the legacies of 1968. As Peniel Joseph, a renowned African American historian writes in The Washington Post, “The flames that engulfed large portions of America during the 1960s helped to extinguish the promise of the Great Society by turning the War on Poverty into a dehumanizing war against poor black communities. America has, in the ensuing five decades, deployed state of the art technology to criminalize, surveil, arrest, incarcerate, segregate and punish black communities. Floyd’s death represents the culmination of these political and policy decisions to choose punishment over empathy, to fund prisons over education and housing and to promote fear of black bodies over racial justice”.

In short, revolutionary moments generate complex and contradictory futures in which progress is often checkmated by reversals, underscoring the fact that history is a dialectical process. The racist backlash against Obama that led to Trump’s election seems to have succeeded in creating an anti-racist backlash.

The America of King’s dream of racial equality and social justice not only remained deferred, but was actively sabotaged by the courts, politicians, and business. The landmark legislative achievements of the civil rights movements, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 wilted as the prison industrial complex, deepening socioeconomic inequalities, and social despair among the poor, both black and white, exploded.

Since 1968, there have been periodic eruptions of protests, most memorably the 1992 Los Angeles uprising following the acquittal of four police officers charged with the widely publicised beating of Rodney King, and the 2014 uprising that began after the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri by a police officer. After each uprising, police, judicial and other reforms were announced, but they largely gathered dust as the protests faded into memory until the next eruption elsewhere.

Only history will tell if the 2020 uprising is different, a transformative watershed in the long history of protests against systemic racism and police brutality. Some are doubtful, others more hopeful. A sample of the divergent opinions can be found among two dozen experts convened by Politico magazine.

Those who doubt that the Floyd protests represent an inflection point worry about the challenges of sustaining the momentum of protest, dynamic grassroots organising and cohesive leadership and unity around a clear set of goals, as well as the powers of state suppression and repression in the reactionary name of “law and order”. Further, hyper-partisanship is more glaring today than ever, facilitated by political polarisation and media fragmentation that make reconciliation difficult.

Those who are more hopeful about the positive impact of the uprising point to the nationwide scale of the protests, the ubiquity of video images of police brutality, and the fact that the protests are occurring in the face of a pandemic and mass unemployment that have disproportionately ravaged people of colour. Moreover, the presence of an outrageously racist, divisive and authoritarian-minded president has increasingly alienated moderate whites.

Many believe the expansive geography of the protests portends its historical significance. In the 1960s, “most protests were held in major cities and on college campuses — and most Americans saw them on the television news”. The 2020 uprising is different. “National media focuses on the big demonstrations and protest policing in major cities, but they have not picked up on a different phenomenon that may have major long-term consequences for politics. Protests over racism and #BlackLivesMatter are spreading across the country — including in small towns with deeply conservative politics. Altogether, according to some counts, the Floyd protests occurred in 1,280 places.

The Floyd moment in which the Black Lives Matter movement is gaining traction in the US and around the world will not be an exception. Progress will be made in chipping away at some of the practices, symbols, and performances of anti-black racism, but the fundamental structures of white supremacy are likely to survive and mutate.

If current polls are to be believed to be harbingers of the future possibilities for transformation, according to The New York Times, “support for Black Lives Matter increased by nearly as much as it had over the previous two years, according to data from Civiqs, an online survey research firm. By a 28-point margin, Civiqs finds that a majority of American voters support the movement, up from a 17-point margin before the most recent wave of protests began”.

The paper continues, “A Monmouth University poll found that 76 percent of Americans consider racism and discrimination a ‘big problem,’ up 26 points from 2015. The poll found that 57 percent of voters thought the anger behind the demonstrations was fully justified, while a further 21 percent called it somewhat justified. Polls show that a majority of Americans believe that the police are more likely to use deadly force against African-Americans, and that there’s a lot of discrimination against black Americans in society. Back in 2013, when Black Lives Matter began, a majority of voters disagreed with all of these statements”.

In short, the 2020 uprising seems to represent progress over 1968 in the scale of its multiracial composition and breadth of demands for racial justice. It suggests white America and other Americans of colour are coming to understand the depth and scope of unrelenting black pain under institutional racism and white supremacy. In the words of Alex Thompson in Politico, “The killing of George Floyd has prompted a reckoning with racism not only for Joe Biden, but for a wide swath of white America,” which he argues could reshape the 2020 elections.

However, given the history of the United States, doubts remain whether this moment represents a defining turning point. The road towards racial equality and justice will continue to be bumpy because what is at stake is the entire system of racial capitalism that reproduces white supremacy, not just its manifestations evident in heinous practices such as police brutality.

What is certain is that the terrain of American race relations is shifting. Floyd’s death has spearheaded the country’s largest and broadest anti-racist movement and made Black Lives Matter an acceptable slogan and not the dreaded and derided radical idea it once was. Behind the movement’s new-found traction lie six long years of tireless work by its activists.

On the Trails of Slavery

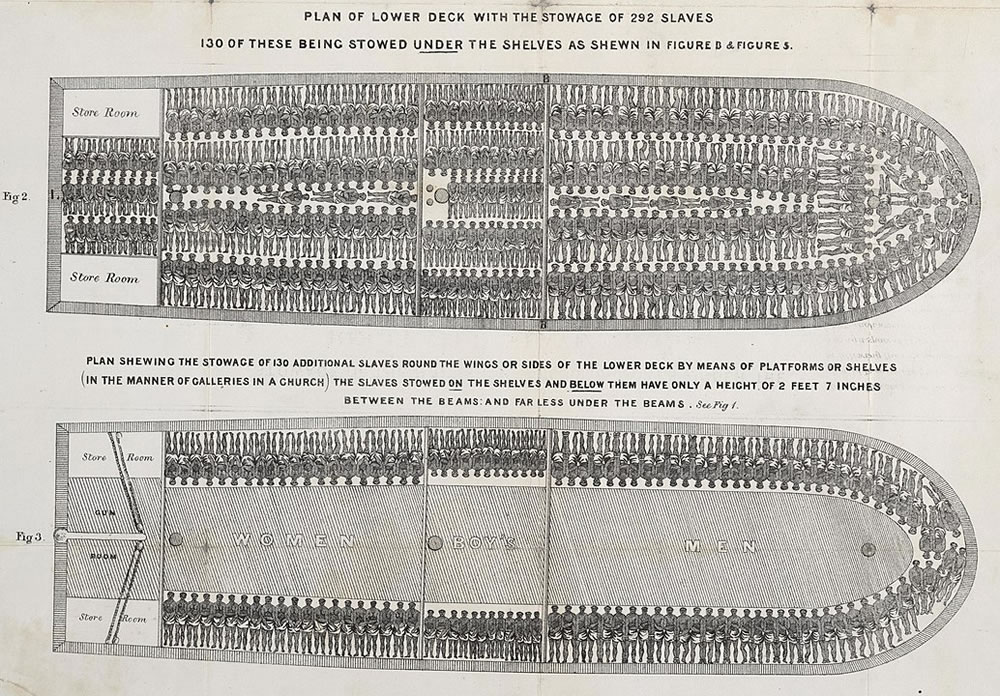

The modern world was created by the triangular slave trade between Africa, Europe, and the Americas. These continents have been linked ever since by the historical geographies and political economies of exploitation and struggle. The US uprising inspired worldwide protests. This reflected the ubiquity of both America as a superpower with an outsize presence in the global imagination and almost universal anti-black racism born out of the Atlantic slave trade that created the modern world.

The protests tapped into growing recognition in many western countries that racism is a problem. According to The Economist, “The share of Americans who see racial discrimination in their country as a big problem has risen from 51% in January 2015 to 76% now. A YouGov poll last week found that 52% of Britons think British society is fairly or very racist, a big rise from similar polls in the past. In 2018, 77% of the French thought France needed to fight racism, up from 59% in 2002. Pew Research found last year that in most countries healthy majorities welcome racial diversity”.

The unprecedented scale of the protests in the US provoked confrontations between the obdurate and callous Trump administration and city mayors and state governors around the country. It produced iconic moments and images. Most graphically, in an act of political pornography and vandalism, there was the picture of Trump awkwardly holding a bible in front of a church after the National Guard had forcibly cleared peaceful demonstrators in Lafayette Square using teargas and rubber bullets. The mayor of Washington responded by painting and ceremonially naming two blocks of the street to the White House Black Lives Matter Plaza. The newly extended perimeter from the White House was turned into an exuberant makeshift exhibition of resistance art, posters, and graffiti.

The America of King’s dream of racial equality and social justice not only remained deferred, but was actively sabotaged by the courts, politicians, and business

Trump’s overreaction triggered a powerful backlash. Widely condemned for accompanying the president to his ill-fated photo-op, the Defense Secretary and Chief of Staff apologised. Several former military leaders expressed disgust and alarm. John Allen, former commander of the NATO International Security Assistance Force and U.S. Forces in Afghanistan, warned: “The slide of the United States into illiberalism may well have begun on June 1, 2020. Remember the date. It may well signal the beginning of the end of the American experiment”.

Other retired military leaders sought to depoliticise their beloved Pentagon from the clutches of the aspiring draft-dodging autocrat. They included John Mattis, who served as Trump’s own Defense Secretary, and Colin Powell, a former Chief of Staff and Secretary of State, who accused Trump of unprecedented divisiveness. The Pentagon promised to review the conduct of the National Guard against the protests. Former presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama expressed their misgivings, and some Republican politicians nervously tried to distance themselves from a president who increasingly looked like a deranged dictator in the mold of the despots he clearly admires and envies.

Before long, anti-racist struggles and protests spread to countries with their own troubled histories of anti-black racism, from Canada to Brazil in the Americas, the former colonial powers of Europe, and the outposts of European settler colonialism in Australasia. Electrifying images were beamed on television stations and social media around the world. A sample can be seen in The Atlantic “Images from a Worldwide Protest Movement”.

In each country and city where the Floyd protests took place, parallels were drawn with local histories of anti-black racism, social injustice, exclusion and marginalisation. The demonstrations and marches were organized by local groups of the Black Lives Matter movement, political and civil society activists, and local groups that had long fought against all forms of exclusion and discrimination. The protests often took place in front of US embassies, national parliaments, public squares, as well as in front of detested statues and monuments to slavery, imperialism and colonialism, and along major thoroughfares.

American diplomats found it galling for the US to be the target of human rights protests around the world as the specious cocoon of democratic exceptionalism spectacularly burst. The New York Times observed, “Diplomats Struggle to Defend Democracy Abroad Amid Crises at Home . . . In private conversations and social media posts… [they] expressed outrage after the killing of George Floyd and President Trump’s push to send the military to quell demonstrations. Diplomats say that the violence has undercut their criticisms of foreign autocrats and called into question the moral authority the United States tries to project as it promotes democracy and demands civil liberties and freedoms across the world”.

The Americas harbour the largest population of the African diaspora mostly descended from enslaved Africans. While there have been some national differences in the constructions of racial identities, since the 16th century the black experience across the region has been uniformly exploitative and oppressive, characterised by slavery, institutionalised racism, exclusion, and police brutality.

Canada — which likes to see itself as the gentler face of North America — is no exception. The country has an ugly history of anti-black racism and genocidal brutality against the indigenous people. Not surprisingly, the uprising in the US resonated in all the country’s provinces and major cities from Halifax, Sydney and Yarmouth in Nova Scotia, where the black loyalists from the American War of Independence settled, to Fredericton, Moncton and Sackville in New Brunswick, St. John’s in Newfoundland, and several cities in Quebec including Montreal, Quebec City and Sherbrooke. Huge protests also took place across Ontario in such cities as Barrie, Hamilton, Kingston, Kitchener, London, Ottawa, Thunder Bay, Toronto, and Windsor, and in the western provinces of Alberta (Calgary, Edmonton, and Lethridge), British Columbia (Vancouver and Victoria and other cities), Manitoba (Winnipeg), and Saskatchewan (Saskatoon and Regina).

However, given the history of the United States, doubts remain whether this moment represents a defining turning point. The road towards racial equality and justice will continue to be bumpy because what is at stake is the entire system of racial capitalism that reproduces white supremacy, not just its manifestations evident in heinous practices such as police brutality.

Unknown to many people is the fact that Mexico has an African diaspora population and that racism is deeply entrenched despite the myths of mestizaje, or racial mixing. White Mexicans have dominated the country and marginalised the indigenous people and African descendants for centuries. Protests and vigils occurred in Guadalajara, Mexico City, and Xalapa. They spread to South America from Argentina (Buenos Aires) that whitened itself in the 19th century through a campaign of black extermination, to Brazil (Curitiba, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo), the country with the largest African diaspora in the world and a horrible history of systemic racism despite the cruel myth of racial democracy, as well as Ecuador (Quito), and Colombia (Bogotá), another country with a massive African diaspora presence.

In the Caribbean, most of the islands have majority African descended populations. Historically, the region’s intellectual-activists played a crucial role in the development of Pan-Africanism. Migration from the region in the 19th and 20th centuries to South and North America and Europe has given its inhabitants intricate global connections so that developments in these regions reverberate with political immediacy. Protests took place in Bermuda, in Kingston, Jamaica, and in Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago.

The protests particularly resonated in Europe with its colonial histories, and failures to integrate recent waves of migrants and refugees from its imperial outposts in Africa and Asia. The black British journalist and academic, Gary Younge, brilliantly dissects the resonance of the American uprising. “Europe’s identification with black America, particularly during times of crisis, resistance and trauma, has a long and complex history. It is fuelled in no small part by traditions of internationalism and anti-racism on the European left, where the likes of Paul Robesson, Richard Wright and Audre Lorde would find an ideological – and, at times, literal – home”.

However, he continues, “this tradition of political identification with black America also leaves significant space for the European continent’s inferiority complex, as it seeks to shroud its relative military and economic weakness in relation to America with a moral confidence that conveniently ignores both its colonial past and its own racist present. From the vantage point of a continent that both resents and covets American power, and is in no position to do anything about it, African Americans represent to many Europeans a redemptive force: the living proof that the US is not all it claims to be, and that it could be so much greater than it is”.

Britain and France, the former colonial superpowers, became the epicenters of large protests in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, and in pursuit of local anti-racism and social justice struggles. Predictably, right-wing politicians and the punditocracy dismissed the solidarity protests claiming, as British black historian, David Olusoga, noted, “The US situation is unique in both its depth and ferocity, they say, so that no parallels can be drawn with the situation in Britain. The smoke-and-mirrors aspect of this argument is that it attempts to focus attention solely on police violence, rather than the racism that inspired it”, which is prevalent in Britain and across Europe.

Olusoga notes that this argument has an old history going back to 1807 “with the abolition of the slave trade and picked up steam three decades later with the end of British slavery, twin events that marked the beginning of 200 years of moral posturing and historical amnesia”. In Britain, demonstrations broke out from May 28 and for the next two weeks roiled all the major cities including London, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Edinburgh, Brighton, Belfast, Oxford, Cardiff, Newcastle, Sheffield, Hastings, Glasgow, Coventry, Nottingham, Carlisle, Middlesbrough, and Wolverhampton. Some believed this marked a turning point in the UK as, in the words of The Guardian, “demands for racial justice now have a new and unstoppable urgency”.

France suffers from a pernicious tradition of colonial denial and amnesia, clothed in facetious fidelity to universal values, which it rationalised at the height of empire with the myth of assimilation. But the country has its own history of police brutality and killings of black people. It was rocked by unrest in Paris, Bordeaux, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, and Toulouse during which protesters invoked George Floyd and their own black martyrs to French racism.

The cities of other former colonial powers were not spared. In Belgium there were widespread protests in Brussels, Antwerp, Ghent, Hasselt, Leuven, Liège, and Ostend. Germany was another centre that saw demonstrations by thousands of people in more than two dozen cities including Berlin, Bonn, Cologne, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Hannover, Leipzig, Munich, Nuremberg, and Stuttgart. Italy was engulfed by protests in two dozen cities including Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Milan, Naples, Palermo, Rome, Turin, and Verona. In Portugal, the last imperial power to be booted out of Africa, thousands of people marched in Lisbon and Porto. Spain, whose African colonial empire was the smallest, a dozen cities witnessed protests including Barcelona and Madrid.

Protests spread to other European countries that had been involved in establishing slave trading forts or colonial settlements across the western seaboard of the African continent. In Denmark, whose slave forts dot the coastline of modern Ghana, hundreds and thousands of people gathered and marched in Aalborg, Aarhus, Copenhagen and Odense. In the Netherlands, the country that gave South Africa its Afrikaner architects of apartheid, solidarity vigils and protests took place from June 1 for the next fortnight in several cities including Amsterdam, Breda, Eindhoven, Leeuwarden, Maastricht, Rotterdam, Utrecht, The Hague, and Tilburg. In Norway, a country that was unified with Denmark during the era of the slave trade, protesters marched in Bergen, Kristiansan, Oslo, and Tromsø.

Such has been the global reach of the uprising against racism and police brutality that other European countries were caught in the turbulence. In Vienna, Austria, more than 50,000 people marched on June 4. Large protests also took place in Sweden in the cities of Gothenburg, Malmö, and Stockholm, while in Switzerland they occurred in Basel, Geneva, Lausanne, and Zürich. Smaller protest marches also took place in Sofia in Bulgaria, Zagreb in Croatia, Nicosia in Cyprus, Prague in the Czech Republic, Helsinki in Finland, Athens and Thessaloniki in Greece, Budapest in Hungary, Reykjavík in Iceland, Cord, Dublin and Limerick in Ireland, Pristina in Kosovo, Vilnius in Lithuania, Luxembourg, Valletta in Malta, Podgorica in Montenegro, Kraków, Poznań and Warsaw in Poland, Bucharest in Romania, Belgrade in Serbia, and Bratislava in Slovakia.

Asia became another theater of Floyd protests although not on the scale of the Atlantic world except for Australia, a settler colony with a notorious history of systemic racism and police brutality against the indigenous people, and Asian and African immigrants. The protests in Brisbane and Sydney attracted tens of thousands of people, and sizable numbers took part in other Australian cities from Canberra, the capital, to Adelaide, Melbourne and Perth.

Hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of people protested in Japan (Tokyo and Osaka), Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea (Seoul), India (Kolkata), Pakistan (Karachi), Sri Lanka (Colombo), the Philippines (Quezon City), Thailand (Bangkok), Kazakhstan (Almaty and other cities), Armenia (Yerevan), Georgia (Tbilisi), Iran (Tehran), Israel (Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa) — led by Israelis of African origin who face racism and disproportionate police arrests — Lebanon (Beirut), and Palestine (Bethlehem).

The protests in the United States and around the world focused on a broadly similar range of targets. First, law enforcement agencies that uphold the system of racial capitalism that marginalises and disempowers black people. Second, the symbols of white supremacy embodied in the public commemorations that honour the perpetrators of enslavement, colonisation, and plunder. Third, private institutions, organisations, and corporations that tolerate and reproduce racial inequalities.

Ironically, it was in Africa where protests over Floyd’s death were relatively muted. To be sure, there were some demonstrations often involving dozens or hundreds of people in several countries such as Ghana (Accra), Kenya (Nairobi), Liberia (Monrovia), Nigeria (Abuja), Senegal (Dakar), South Africa (Cape Town, Johannesburg, and Pretoria), Tunisia (Tunis), and Uganda (Kampala). More extensive and powerful expressions of solidarity were vented in petitions by activists, intellectuals, and artists (I participated in one called “We Cannot Remain Silent”), and especially on social media, according to Nana Osei-Opare writing in the Washington Post. This intriguing phenomenon reflects three complex factors.

First, in spite of Pan-Africanist rhetoric among African leaders and intellectuals, it reflects an enduring disconnect between Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. It is borne out of limited engagements that ordinarily would emanate through the educational system and other forms of positive mutual exposure. Instead, there is an overexposure to negative stereotypes in the media that often traffic Eurocentric constructs and tropes on both sides of the other’s “civilisational” lack. More deeply, the unknowing of the diaspora, the willful ignorance of its tribulations, elides Africa’s complicity in the very creation of the Atlantic diasporas through the slave trade.

Second, is the ambivalent postcolonial mindset rooted in the colonial denial of African humanity and historicity. It is a miscognition that simultaneously breeds resentment of the empire and craving of its prowess. This generates a strange desire to be embraced and absorbed into the empire’s imagined superiority and advancement enveloped in the whiteness that the colonised strives for but, like Sisyphus, is destined never to attain, thereby inducing a state of perpetual self-doubt and self-denial. This fosters both envy of the diaspora ensconced in the heart of empire and blindness to its plight, a slippery disposition that engenders a deficit of sympathy and often slides into blaming the victim.

Third, there is what I would call the shortage of surplus political capital for solidarity, the dispositions to accommodate transnational diaspora struggles. Surplus capital can be externalised for better or ill as evident in the impetus for new imperialism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Save for their elites, many African communities in their protean daily lives, now made infinitely worse by the coronavirus pandemic, are fettered by debilitating economic, political, and social conditions and perpetual struggles against often autocratic regimes or illiberal democracies whose law enforcement agencies have retained the deformities of colonial state violence and repression.

Reclaiming Public Memory

The monuments that have become the focus of public protests, accompanied by demands for more accurate, holistic and inclusive historical representations, are part of the struggles for liberating highly sanitised and racialised public spaces and memories. The protesters seek to insert African-descended peoples and their invaluable contributions in the national and regional histories of Euroamerica.

The removal and desecration of racist monuments offer a powerful rebuke against the brazen glorification of imperial and colonial conquests, exploitation, and oppression. These acts of iconographic liberation strike at the willful production of ignorance and limited understanding about the unsavory histories that made Euroamerica through the educational system, popular histories, and films and television. They have been targeted for decades as offensive symbols and reminders of slavery and racial oppression.

The conversations forced by the assault on racist monuments provoke much-needed historical reckoning and accounting for the persistent racial inequalities, injustices, and hierarchies bequeathed by enslavement, colonialism, and empire. They help dismember contemporary constructions of belonging and citizenship, of who constitutes and can enjoy the rights of the social and political community of the nation-state in Europe and the settler societies of the Americas and Australasia.

In the US, the removal of the statues and symbols of the renegade losers of the civil war who fought to retain slavery has intensified and reached the hallowed halls of Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi urged the removal of 11 statues representing Confederate leaders and soldiers, noting that the “statues pay homage to hate, not heritage”. The Pentagon announced its willingness to rename military bases associated with Confederate figures, a move that was endorsed by the Republican-controlled Senate despite Trump’s expressed opposition.

The scale of the task is huge as there are about 1,800 Confederate symbols across the US (776 of which are monuments), and only 141 (61 of them monuments) have been removed, and seven are pending removal. For their part, “the Navy and Marine Corps announced that they will ban the display of the Confederate flag at their facilities and events. Church symbols have not been exempt. The president of the Southern Baptist Convention “called for the retirement of a gavel that carries the name of a 19th-century Southern Baptist leader who was a slaveholder and led the convention in support of the Confederacy”. He proceeded to say “‘black lives matter’ six times in his presidential address”.

In Britain, protesters toppled the statues of slave traders including Edward Colston in Bristol, and Robert Milligan in London. City councils under the Labour Party led by the capital, London, announced their intention to set up commissions to review sculptures, buildings and street names associated with slavers, while Conservative councils came under increased pressure to do the same. Activists hoped the toppling of the public memorialisations of the symbols of slavery and colonialism would force the country to confront the sordid historical injustices that had shaped it.

Several institutions including hospitals and universities also began the process or conversations to remove historical figures associated with the slave trade. Calls intensified for the disposal of the notorious imperialist Cecil Rhodes, a campaign that began in 2016 on the heels of the RhodesMustFall campaign at the University of Cape Town, and racist icons of the British establishment such as Winston Churchill and Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouts movement. But Catherine Bennet cynically that, “As statues of slave traders are torn down, their heirs sit untouched in the Lords”.

In Belgium the statue of King Leopold II of Belgium, the architect of one of the worst genocides of the 20th century that decimated 10 million people in the Congo, was removed in Antwerp. In Spain debate was rekindled for the removal of the statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona — which some councilors had voted for in 2016 — for its glorification of the conquest of the Americas and for its replacement by a memorial of those who resisted imperialism and the oppression and segregation of the indigenous people and enslaved Africans and their descendants.

The removal of the statues of slave traders and imperialists in Europe is a homage to the unfinished project of decolonisation that began after World War II. The struggle over historical memory, constructions, and emblems is about the legacies of the past that disfigure the present and threaten to burden the future if reckoning and resolution continue to be postponed. The refusal to deal with the past and its stifling shadows on contemporary society is infantile and an ingrained part of the repertoire of anti-black racism in the Americas, Europe, and elsewhere. Removing statues is of course a symbolic act, but symbols matter. As Eusebius McKaiser reminds us, “We know from South Africa that toppling statues is no silver bullet – but it’s a start”.

Thus, at stake in the political and discursive struggles over the statues is collective public denial or willingness to reckon honestly with the complicated and messy histories and persistent legacies of slavery and empire, to dismantle false national mythologies and self-righteous delusions that breed shameless hypocrisies and perpetuate human rights abuses. Many of the contested statues were created decades or even centuries after the individuals or events their creators sought to glorify (in the US the Confederate monuments were created as part of the revisionist romanticisation of the “Lost Cause”). This underscores the fact that they were built to augment the arsenal of selective political constructs in the ignominious service of white supremacy.

Performative Activism

The struggles to reclaim public spaces and historical memory from the accretion of generations of racist practices and ideologies is leading powerful institutions and individuals to embrace performative anti-racist activism that does not cost them much but serves to burnish their brands. The growing traction of the Black Lives Matter movement in public opinion has raised the opportunity costs of casual anti-black racism as a majority of Americans have increasingly come to believe that racism is a problem in the US.

This moment has ironically been facilitated by Trump’s presidency, which is characterised by unabashed racism, dizzying incompetence, authoritarian impulses, and perpetual chaos. Trump has succeeded in accelerating the erosion of the conservatism he was elected to protect from the country’s changing demographics and liberal drift. Thus, the Trump administration, which emerged out of a racist backlash against the Obama presidency, has helped both to reinforce and upend systemic racism and white supremacy.

Trump simultaneously brought racism out of the post-civil rights closet and made racism increasingly embarrassing to the so-called middle America of moderate whites and unacceptable to younger white Americans more exposed to multiracial experiences and expectations, not least because of the symbolic possibilities of the Obama presidency notwithstanding all its limitations. The national uprising has been remarkably multiracial, far more than the civil rights struggles of the 1950s and 1960s. It has been dominated by young people, as revolutionary moments tend to be.

Trump’s victory often obscures the fact that the shifts in racial attitudes began earlier. One observer contends that “For all the attention paid to the politics of the far right in the Trump era, the biggest shift in American politics is happening somewhere else entirely”, namely, in the move to the left of white liberals on questions of race, racism and other priorities of the Democratic coalition such as immigration reform. He calls it the “Great Awokening” that began with the 2014 protests in Ferguson. “Opinion leaders often miss the scale and recency of these changes because progressive elites have espoused racial liberalism for a long time”.

A poll published on 9 June 2020 found that “nearly two-thirds of Americans, including 57% of whites, are ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ concerned about systemic racism”. It is this shift in public opinion that makes performative support for anti-racism more imperative for more constituencies and actors in the public and private sphere, from corporations to the media, sports and academe. The New York Times puts it pithily, “From Cosmetics to NASCAR, Calls for Racial Justice Are Spreading. What started as a renewed push for police reform has now touched seemingly every aspect of American life”.

Racist behaviours and statements that would previously have been ignored increasingly threatened the careers and social standing of their perpetrators as the opprobrium for anti-black racism rose. It became a season of apologies from media personalities, sports figures, university professors, publishers, and film directors, for the offensive statements they had made in the past or following Floyd’s horrific killing.

The public imagination was especially captured by the apologies and the affirmations that Black Lives Matter by sports figures. The NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell stated, “We the National Football League, condemn racism and the systematic oppression of black people”. He went on to stress, “We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest”. Confronted by criticism that he did not mention Colin Kaepernick, a quarterback who popularised kneeling during the national anthem as a form of protest against police brutality, he later did so and appealed for Kaepernick’s reinstatement. NASCAR, especially popular among Southern whites, announced the banning at its events of Confederate flags — a despised symbol among African Americans — which it had discouraged since 2015 to no avail.

Apologies and protests spread to the rarefied white-dominated world of fashion as the editor-in-chief of American Vogue, Anna Wintour, apologised for publishing hurtful or intolerant stories and not hiring enough people of colour. The editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer resigned “after an article with the headline ‘Buildings Matter, Too,’ on the effects of civil unrest on the city’s buildings, led to a walkout by dozens of staff members”.

For their part, “more than 300 leading stage artists signed a letter decrying racial inequality in the world of ‘White American theater’”. Some musicians converted to the new anti-racist tune: “Lady Antebellum, the Grammy-winning country music trio behind one of the highest-selling country songs of all time, is dropping the “antebellum” from its name”, wrote The Washington Post. The cinematic arts also saw the light. Television shows, such as Cops, and films, such as Gone with the Wind, that glorify police violence and elide the brutalities of slavery, were terminated or removed from streaming. However, critics maintained that censoring old films and TV shows was not enough; what mattered was employing more people of colour in the industry.

Restiveness among technology companies also became evident. The announcement by IBM and Amazon that they were withdrawing their face recognition technology from use by police forces in racial profiling and mass surveillance was widely hailed in some quarters. In the meantime, “More than 200 Microsoft employees have signed a letter calling on the company to stop supplying software to law enforcement agencies; to support efforts to defund the Seattle Police Department; and to join a call for the mayor of Seattle, Jenny Durkan, to resign. The signers are a tiny fraction of Microsoft’s more than 140,000 employees. But the letter is another sign of increasing activism by employees at major technology companies on a range of political issues, which executives have been forced to address — if only to explain why they would not comply with workers’ requests”.

Performative anti-racist solidarity was also expressed in other countries, although to a more limited extent. In Britain, the tea-obsessed nation paid attention when “Top U.K. Tea Brands Urge #Solidaritea With Anti-Racism Protests”, to quote a headline from a story in The New York Times. The story noted that a series of tea companies doubled down following right-wing complaints about businesses’ support for Black Lives Matter.

Clearly, as silence on race increasingly ceased to be an option, American companies and institutions fell over each other to proclaim their support for Black Lives Matter. Anti-racism suddenly became a badge of honour for companies eager to burnish their brands under America’s emerging new normal. Corporate America proudly wore its newly acquired conscience on its malleable sleeves.

The bandwagon expanded by the day and encompassed every sector as noted in the following partial list. Automobile industry: BMW, General Motors, Lexus, Mercedes Benz, and Porsche. Banking and finance: American Express, Barclays Bank, Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, MasterCard, Wells Fargo. Delivery services: FedEx, and DHL. Film and Television: The Academy, Cartoon Network, DIRECTV, Disney, ESPN, HBO, Paramount Pictures, Nickelodeon, Fox, Hulu, IMAX, Netflix, Showtime, STARZ, Star Wars, Warner Bros, and YouTube. Gaming: Astro Gaming, GameSpot, Nintendo, PlayStation, Pokémon, XBox, Sony, Nintendo, EA, Ubisoft, Take-Two, Square Enix, Riot Games, Rockster Games, Bethesda, and Capcom.

Health and Insurance: MetLife, New York Life, UnitedHealth Group. Food and Beverages: Ben & Jerry’s, Burger King, Chipotle, Chick-fil-A, Doritos, Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, Gatorade, Popeyes Chicken, McDonald’s, Pop Tarts, Red Lobster, Subway, Starbucks Taco Bell, and Wendy’s. Music and performance: Atlantic Records, Billboard, Capitol Records, Virgin Records, Warner Records, and Metropolitan Opera. Oil and gas: BP. Pharmaceuticals and pharmacies: Bauer, CVS, Merck, and Pfizer. Publishing: Condé Nast.

Retail and grocery stores: American Apparel, Adidas, Armani, Burberry, Foot Locker, Gap, H&M, Home Depot, Huckberry, IKEA, Lacoste, Levi’s, Nike, Nordstrom, Reebok, Proctor & Gamble, PUMA, Target, Vans, Versace, Zara, Lowe’s, Sephora, and Tesco. Sports: NASCAR, and NFL. Technology and e-commerce: Apple, Cisco, Dell, Dropbox, eBay, Facebook, Google, HP, Inivision, IBM, Intel, Lenovo, LinkedIn, McAfee, Microsoft, Mozilla, Qualcomm, Reddit, Snapchat, Salesforce, Shopify, Spotify, TikTok, Tinder, Tumblr, Twitter, and Zoom. Telecommunications: AT&T, Verizon, TMobile. Transport: Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, Lyft, and Uber.

The flood of corporate anti-racist statements was often accompanied by donations to venerable civil rights organisations such as the NAACP, Urban League, and National Action Network, and other groups fighting racial inequality. They also made vague promises to promote diversity and inclusion in their own companies without spelling out meaningful enforcement mechanisms. The donations tended to be largely token, but some were sizable. For example, SoftBank allocated of $100 million to invest in minority entrepreneurs, while “PayPal, Apple and YouTube collectively pledged $730 million to racial justice and equity efforts”. Estée Lauder, the cosmetics giant, raised its donation from $1 million to $5 million when its initial offer was derided by employees who compared it unfavorably to Mr. Lauder’s far more generous donations to Trump.

Many corporate executives saw the anti-racism cause as part of their corporate social responsibility, which for some amounted to political corporate social responsibility. In 2019, 181 US corporations signed a revised statement on the purpose of a corporation, issued by Business Roundtable. The corporate executives committed to lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders by “Delivering value to our customers”, “Investing in our employees”, “Dealing fairly and ethically with our suppliers”, “Supporting the communities in which we work”, and “Generating long-term value for shareholders”.

While welcoming pledges by corporations to engage in anti-discrimination efforts and programmes to support black businesses and communities, many black corporate leaders and civil rights activists remained skeptical as noted in a long article in The New York Times, entitled “Corporate America Has Failed Black America”. They emphasised the need to tie executive pay to diversity metrics, which a few companies such as Microsoft, Intel and Johnson & Johnson had embraced.

By and large, critics of corporate America were not impressed by its performative anti-racism. They bemoaned the glaring gap between its fluffy anti-racist rhetoric and the reality of entrenched racist practices in most American companies. Some of the advice given to companies by their cheerleaders exacted little cost. One corporate sympathiser urged them to expand their relationships with historically black colleges and universities, advertise more openly, create diverse interview panels at all levels, provide extensive sensitive training for all employees, and set the tone for inclusion at the top.

The Economist contended, “Good intentions of bosses aside, untangling the problem of race and corporate America requires addressing four questions. First, what is the evidence that blacks are disadvantaged in the workplace? Second, how much is business to blame rather than society as a whole? Third, do any such disadvantages impact how businesses perform? And finally, what if anything can business do to improve matters?”

Its answer to all four questions underscored the prevalence of systemic racism and black under-representation throughout American business. It concludes, “Experts recommend creating a diversity strategy specifically for black employees, implementing clear and consistent standards for promotion and securing a firm commitment from the top to overcome bias among middle managers . . . That points to the importance of metrics and measurement”.

The rhetorical anti-racist bandwagon grew with breathtaking speed that confounded many people. Unhinged white conservatives bemoaned the trend, redoubled their virulent attacks on the Black Lives Matter movement and denounced the protesters as rioters and even domestic terrorists. Anguished white liberals shed their silence and commiserated with each other about racism and inundated their black colleagues with outpourings of sympathy, support and queries, which some blacks welcomed and others disdained. The latter resented the added burden of cleansing white consciences.

For their part, African Americans seized this rare opportunity to be heard by the wider society, unleashing an avalanche of tales of painful and often harrowing experiences with racism in their daily lives which they often hide from their white colleagues. New social media tags were created, such as #BlackInTheIvory that has been deluged by stories of the marginalisation, isolation, devaluation, frustration, and hostility experienced by black academics. Sales of books on race and racism, many by black authors, skyrocketed. The uprising also inspired thousands of people in the US and around the world to create powerful art. From “street murals near the White House to editorial comics created near where Floyd died, artists are delivering political messages through often stark imagery”.

The battles over racism and the protests raged on social media, the public square of the digital age. They engulfed platforms often not in the public eye. For example, as reported by The New York Times, “Upper East Side Mom Group Implodes Over Accusations of Racism and Censorship. A large Facebook parenting group temporarily shut down after silencing black members. Now new groups for parents are forming that are explicitly anti-racist.”

Trouble in the Ivory Tower

Colleges and universities were embroiled in the sprawling national crisis, although closures of campuses in response to the coronavirus pandemic saved them from protests on their own campuses and in university towns. Linda Ellis warns in The Chronicle of Higher Education (June 12, 2020) that, “For Colleges, Protests Over Racism May Put Everything On the Line”. She predicts the reckoning will come once colleges and universities reopen and as students return to campuses, already energised by the national uprising triggered by Floyd’s horrific killing.

Many universities issued statements expressing sympathy, pain, even support for Black Lives Matter. Predictably, the statements vary in length, depth and breadth. Many were formulaic and fluffy, written by communication departments afraid of antagonising powerful donors, state lawmakers, and alumni. They invoke the role of the university as a positive force in society, forgetting the fact that American universities and education in general have been integral to the production and reproduction of the structures and ideologies of systemic racism.

As numerous studies have shown, building on Craig Steven Wilder’s groundbreaking Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities, many of the renowned Ivy League universities were founded by or with resources from slave owners and slave traders. Over the generations, the ideologies and practices of anti-black racism have been concocted, refined and sanctified in the academy. Black history, contributions, concerns, interests and experiences are routinely excluded and devalorised in the American academy.

The constant assaults and surveillance of racism in the white academy is for black students and faculty are draining and exhausting. Some succumb to the stresses of racial battle fatigue and become less productive and alienated from a vocation they had chosen with such passion and expectation. They become retired on the job in that they check out and go through the motions of their jobs. Others persist and become adept at concealing the pain, humiliation, and hostility they often face. However, professional progress offers no immunity. In fact, the higher one rises, the more one is surveilled in the fishbowl of systemic racism that permeates American academic cultures and institutions.

African American students and academics are grossly underrepresented in the prestigious universities, programmes, and fellowships, while black-centred knowledges are often filtered out from the holy grail of academic publications, journals, grants, and conferences. There are of course differences according to discipline and field. The situation in the sciences is particularly egregious.

On June 10 2020, almost 6,000 scientists and academicians participated in a one-day strike. The event was organised under various hashtags, including #Strike4BlackLives, #ShutDownStem and #ShutDownAcademia, by scientists who complained about pervasive racism in science. Besides classes, several leading scientific journals, such as Nature, Science, Physical Review Letters and arXiv, cancelled activities that day.

Protests spread to some academic journals and their editors. For example, after writing a tone-deaf tweet criticising the Black Lives Matter movement as “flat earthers”, an array of economists that included the former chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, and Paul Krugman, a Nobel prize winner, called for the resignation of Harald Uhlig, the editor of Political Economy Review. In the US economics as a field is white male-dominated, which has led to the devaluation of research and publications by women and blacks and on gender and race.

I can relate to the challenges faced by African Americans in the academy. As a college dean and an academic vice president at predominantly white universities in California and Connecticut, respectively, I was subject to doubt and disrespect that none of my colleagues in similar positions experienced. As is all too common, I was the first black person to occupy those positions. Earlier in my career when I served as director of one of the largest centers for African Studies at a Research 1 university in the Midwest, I witnessed the exclusion of Africans and African Americans in the study of their own ancestral continent, Africa.

It became too much for me and, fortunately, I was able to flee to Kenya. I often commiserate with my friends and colleagues that I left behind, some of who have risen to higher positions as deans, provosts, and presidents. They continue to walk the fine line of racial discrimination and exclusion in the American academy. In the aftermath of the uprising many of them have courageously stepped up to denounce systemic racism and call for honest dialogue and real change on their own campuses and share their pernicious experiences with racism as black men and women.

Taming Law Enforcement

A key demand of the protesters has been the urgent need to address systemic police brutality, racial bias, misconduct, and unaccountability. The evidence of racism in the criminal justice system is overwhelming as an exhaustive list of studies in The Washington Post shows. As if to prove the Black Lives Matter movement right, the police reacted to the demonstrators with excessive force and brutality that resulted in 11 deaths and nearly 10,000 arrests within a fortnight. This galvanised the protest movement even further. The public and elected leaders could no longer ignore police behaving as an invading army and the armour of police untouchability began to crack.

To be sure, there were occasional scenes of police officers kneeling in solidarity withthe protesters. Some African American police chiefs — who are always caught between their racial identity and police fraternity — shared their agonies, dilemmas, challenges, and frustrations in trying to change their departments from within and reconcile their personal and professional, private and public lives.

Police Departments across the country came under pressure to review their policies and practices as public agitation for comprehensive police reform mounted. City councils, state assemblies, and Congress were forced to begin enacting long-standing demands and legislation banning grievous repressive practices and promoting police reform. For some, more radical measures were needed, and they adopted the slogan “Defund the Police”. The Center for Community Change Action framed the much-needed restructuring in terms of redistribution for reconstruction, taking funds from law enforcement to improve health care, education, and other social services and opportunities in communities of colour.

In the House of Representatives, Democrats unveiled the Justice in Policing Act of 2020 whose provisions included requiring police to use body and dashboard cameras, restricting the transfer of military equipment to police, prohibiting chokeholds and unannounced raids through the issuance of no-knock warrants, enhancing police accountability by restricting the application of the qualified immunity doctrine that makes it difficult to prosecute law enforcement personnel, establishing a federal registry of police misconduct complaints and disciplinary actions, granting power to the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division to issue subpoenas to police departments with a pattern and practice of bias or misconduct, and requiring state and local law enforcement agencies that receive federal funding to adopt anti-discrimination policies and training programmes.

Republicans were caught flat-footed. The New York Times noted that, “Having long fashioned themselves as the party of law and order, Republicans have been startled by the speed and extent to which public opinion has shifted under their feet in recent days after the killings of unarmed black Americans by the police and the protests that have followed. The abrupt turn has placed them on the defensive”. They charged the only black Republican Senator, Tim Scott, to draft their own bill on police reform.

On 17 June 2020, Republicans “unveiled a policing reform bill that would discourage, but not ban, tactics such as chokeholds and no-knock warrants, offering a competing approach to legislation being advanced by House Democrats that includes more directives from Washington. The Republican proposal, which Senate leaders said would be considered on the floor next week, veers away from mandating certain policing practices, as the Democratic plan does . . . Prospects for reaching common ground in the coming weeks remain unclear”. The stage was set for a legislative brawl between the two parties, whose outcome was unpredictable.

Under mounting pressure, President Trump had issued an executive order the previous day. He offered tepid “support for curtailing police abuses while reiterating a hard line on law and order”, reported The Wall Street Journal. The order “has three main components: establishing an independent credentialing process to spur departments to adopt the most modern use-of-force practices; creation of a database to track abusive officers that can be shared among different departments; and placing social service workers to accompany officers on nonviolent response calls to deal with issues such as drug addiction and homelessness. Chokeholds would be banned under the recommended standards, Mr. Trump said, unless an officer’s life is at risk”.

Within two weeks of the national uprising following Floyd’s death, several states and cities had enacted legislation to reform the police services along some of the lines of the Democratic bill in Congress. The New York state assembly passed a bill allowing felony charges to be brought against police using chokehold or similar restraint, and for the release of disciplinary records of individual police officers, firefighters or corrections officers without their written consent. The governor ordered all police departments to develop and obtain approvals for reform plans by April 1 2021 in order to remain eligible for state funding, while the mayor of New York City announced plans to shift some funds from the police department’s $6 billion budget to other services.

Los Angeles cut funding by US$150 million from its police department. In Seattle, the mayor promised to invest US$100 million in the Seattle Black Commission for community-driven programmes for black youths and adults. The Minneapolis City Council voted overwhelmingly to abolish the police department. In Louisville, Kentucky, the City Council unanimously passed “Breonna’s Law” that banned the use of “no-knock” warrants, named after Breonna Taylor who was killed in her own home. In Washington DC the City Council also banned the use of tear gas, pepper spray, rubber bullets and stun grenades to disperse protesters.

Some critics maintain focusing on the police is not enough. In the words of Charles Blow, “But, these bills, if they pass as conceived, would basically punish the system’s soldiers without altering the system itself. These bills would make the officers the fall guy for their bad behaviour while doing little to condemn or even address the savagery and voraciousness of the system that required their service. This country has established a system of supreme inequity, with racial inequity being a primary form, and used the police to protect the wealth that the system generated for some and to control the outrages and outbursts of those opposed to it and oppressed by it. We need more than performative symbols of solidarity. We need more than narrow, chaste legislation”.

The slogan “Defund the Police” turned into a battle cry for the supporters and opponents of comprehensive police reform. For its proponents this is a demand for a fundamental reimagining and restructuring of American law enforcement from its roots in the systemic racism and white supremacy of slave patrols that evolved into the gendarmes of Jim Crow and subsequent crackdowns on black protests and the highly racialised “War on Drugs.”

The critics argue that the nearly US$100 billion spent on law enforcement could be used, to quote Paige Fernandez, the Policing Policy Advisor of the American Liberties Union, writing in Cosmopolitan, to fund “more helpful services like job training, counseling, and violence-prevention programs . . . Funneling so many resources into law enforcement instead of education, affordable housing, and accessible health care has caused significant harm to communities”.

The author reminds her readers that, “Much of the work police do is merely engage in the daily harassment of Black communities for minor crimes or crimes of poverty that shouldn’t be criminalized in the first place. Consider this: Out of the 10.3 million arrests made per year, only 5 percent are for the most serious offenses, including murder, rape, and aggravated assault. These are the ones that truly threaten public safety . . . That means that police spend the most resources going after minor incidents that actually don’t threaten everyday life but do lead to mass criminalisation and incarceration”.

The brutality of police forces escalated with their militarisation, a process that accelerated, writes Simon Tisdall in The Guardian, in response to “the 9/11 attacks, when George W Bush plunged the country into a state of perpetual war. Paradoxically, his ‘global war on terror’ intensified international and domestic insecurity. It sparked a huge, parallel expansion in the powers and reach of the homeland security apparatus. As Pentagon spending grew to a whopping $738bn this year, total police and prison budgets have also soared, reaching $194bn in 2017. About 18,000 law enforcement agencies employ 800,000 officers nationwide. Many are armed to the teeth”. In short, the crisis of policing in the US flows from the devil’s brew of entrenched racism, excessive militarism, xenophobic nationalism, and imperial decline.

Transforming Racial Capitalism

Many leaders and opinion makers in political, business, media, and academic circles promote legislative and policy solutions as antidotes to systemic racism. However, anti-black racism has persisted despite the enactment of a myriad of laws and policies since the 1960s. White supremacy and its pathological disdain for black people, black bodies, and black humanity emanates from deep cultural and cognitive spaces that lie beyond the reach of well-crafted legislation and policy pronouncements.

In short, the struggle to eradicate systemic racism and white supremacy has to transcend police reform and electoral politics. After all, racial bias, violence, and inequality have persisted under Republican and Democratic administrations alike, including Obama’s own, and under black leaders in state assemblies and black mayors in cities. Thus, for young African Americans who have grown up in cities and in a country with thousands of elected black officials compared to the 1960s, the promises of electoral politics do not carry the same transformative appeal.

As in Africa following decolonisation, achieving political representation, a worthy goal in itself, is inadequate for the herculean task of fundamentally changing the structures of economic and political power and systemic racism in the United States. The younger generations demand, and are seeking to build, a new black and national politics of accountability and transformation.

The complicity of Democratic presidents, senators, and congressmen and congresswomen in the construction of the prison-industrial complex since the 1980s is all too well known. President Clinton’s crime and welfare reform legislation fueled mass black incarceration and impoverishment. For his part, President Obama failed to meet the radical expectations placed on his administration in terms of reforming the criminal justice system, reducing economic inequalities, and curtailing the corporate power that engendered the Great Recession. Whereas Clinton passed draconian immigration law, Obama’s deportation of undocumented immigrants reached record levels.

Fundamental change requires a much broader and bolder vision and an expansive and inclusive politics. It has to transcend the paralysing dogmas of neo-liberalism and encompass transforming the multiple structural pillars and cultural dynamics of racial capitalism, as well as building new multiracial and class coalitions and alliances. There is no shortage of blueprints for a different future from America’s radical thinkers and activists committed to building a future envisaged in Martin Luther King’s dream of a “beloved community” based on the pillars of economic and social justice free from poverty, discrimination, and violence.

Danielle Allen suggests creating a new national compact that encompasses some of the following elements: expanding the House of Representatives, adopting ranked-choice voting, instituting universal voting and instant voter registration for all eligible Americans, establishing an expectation of national service by all Americans, limiting Supreme Court justices to 18-year terms, building civic media to counteract the challenges introduced by social media, finding honest ways to tell the nation’s story, and increasing “resources and resolve for community leadership, civic education and an American culture of shared commitment to constitutional democracy and one another”.

In the magazine, Harvard Gazette, a group of six of the university’s faculty members discuss “how best to convert the energy of this moment into meaningful and lasting change”. Some explicitly support or echo the demands of the Black Lives Matter movement. More specifically, they variously propose a serious reckoning of the foundational exclusions of African Americans and Native Americans; the pursuit of economic democracy; the need for a new Voting Rights act and a a Third Reconstruction involving “a fundamental reconsideration of our Constitution, systems, institutions, and practices to uphold human rights and ensure equal opportunity for all”. Centring black women in the struggle for collective liberation is imperative, and for the university itself “to move beyond the rhetoric of ‘diversity and inclusion’ and become anti-racist”.

Michele Alexander, the author of the influential book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, admonishes the nation in The New York Times. “America, This is Your Chance. We must get it right this time or risk losing our democracy forever”. She implores the country’s diverse citizens, “We must face our racial history and our racial present”, “We must reimagine justice” beyond tinkering with token or unsustainable fixes, “We must fight for economic justice” by transforming the economic system, and embracing one based on economic justice.

For some, economic justice also entails reparations, an issue that is gaining some traction. The reparations movement has a long history, but it has remained on the fringes of American intellectual and political discourse. An influential essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates, the African American writer who some regard as a successor to the great James Baldwin, “The Case for Reparations” published in The Atlantic in June 2014, brought the issue to the mainstream media. He argues powerfully, “Two hundred fifty years of slavery. Ninety years of Jim Crow. Sixty years of separate but equal. Thirty-five years of racist housing policy. Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole”.

The data on what America owes African Americans is damning. In her book, The Color of Money, Mehrsa Baradaran offers a bleak assessment of the racial wealth gap and the limits of community self-help. She shows that in 1863 when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, the black community owned 0.5 per cent of the country’s wealth. More than 150 years later this rose to a paltry 1 per cent! In a recent interview, she argues, America has repeatedly violated its promises of equal protection, equality and equality to African Americans. To quote her, “I teach contract law”, she states, “When you break a contract, you pay damages. We’ve broken the contract with Black America . . . We embedded racism into policy. And how do you get that out. How do you fix that? I think reparations is the only answer . . . And I think a process of reparations should involve truth and reconciliation. We have the funds. We saw this with the coronavirus. Over a weekend, the Fed infused trillions of dollars into the repo markets and into the economy. We don’t have limits of resources. We have limits of empathy and imagination”.

The need for white involvement in the anti-racist movement is well understood. No less critical is building strong multiracial alliances among America’s racial minorities, who collectively will in a couple of decades become the country’s majority. Each minority group has its own complex history and positioning in the country’s racial hierarchy and political economy. Particularly divisive has been the model minority myth applied to Asians, which some Asian Americans have embraced and internalised. It was constructed, and serves, to distance them from African Americans and Hispanic Americans.

Differentiation and distanciation from African Americans is the ritual of passage to Americanisation by every migrant group in the United States. Successive waves of Europeans from Irish, Italian, Slavic, and Jewish backgrounds were initially not considered white, but were eventually absorbed into whiteness, a process that often entailed socialisation into American racism. Asians, whose migration to the United States increased following changes in migration law due to the civil rights movement, have reveled in being called a model minority. Even immigrant Latin Americans and Africans seek dubious solace in their foreignness, in not being African American until they are brutalised by systemic racism and white supremacy. The 2020 uprising has brought a lot of soul searching for every racial group in the United States in terms of where they stand in the country’s enduring racial quagmire.

The national uprising has emboldened Asian American activists to call for solidarity with African Americans in struggles against systemic racism and white supremacy. Marina Fang notes, “George Floyd’s death has galvanized some Asian Americans to try to start conversations with their families about anti-Black racism” and build solidarity with Black communities. “Anti-Black racism in Asian communities is tied to the ‘model minority’ myth, which white political leaders, particularly in response to the civil rights movement in the 1960s, wielded in order to drive a wedge between Asian Americans and other people of color”.

Writing in The Washington Post, Prabal Gurung echoes the same sentiments, “It’s time for Asian Americans to shed the ‘model minority’ myth and stand for George Floyd”. He stresses, “Beyond simple divestment and rejection of our own trope, we must also actively combat anti-blackness — especially within the Asian community . . . To break from this cycle, we must begin by asking: Who benefits when minority groups fight each other or are apathetic to one another’s struggles? . . . It is time for us to stand in solidarity with black communities whose sacrifices led to the civil rights and privileges we benefit from”.

The Washington Post reported during the protests, “Many Asian Americans say they feel a need to show solidarity with black protesters . . . Asians have their own history of American discrimination from the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II to the slurs and boycotts Asian American restaurant and business owners have faced during the coronavirus pandemic”. One Asian American protestor “said his generation is well aware that the success Asians have achieved in the United States is owed directly to black protesters in the 1950s and 1960s and is built “on the backs of those black leaders of the civil rights movement”.

The uprising has also forced many whites to accept that silence is complicity and to confess their ignorance about the depths of American racism. David Axelrod, the chief strategist for President Obama’s campaigns and senior advisor in the Obama White House, puts it poignantly in The Washington Post, “I thought I understood issues of race. I was wrong”. He goes on to state, “Despite my work, I was too often oblivious — or at least inattentive — to the everyday mistreatment of people of color, including friends and colleagues, in ways large and small. Although I was reporting on the issues of police brutality and unequal justice as a journalist, I didn’t experience it. My kids didn’t experience it. And I never really engaged my black friends and colleagues about their own experiences. I never asked, so far as I can remember, about their own interactions with police or their fears for their children”.

It is worth quoting Axelrod’s conclusion: “A lot of white Americans thought they understood. But the underlying legacy of racism still remains. The laws that were passed were hard-won and important, but they didn’t eliminate deeply ingrained biases and layers of discriminatory practices and policies that mock the ideal of equality. The election of a black president was a watershed event in our history that struck at the heart of the racist creed. But it didn’t end racism. In fact, it provoked a backlash that empowered a racist demagogue and new policies meant to further embed structural barriers to full citizenship for black Americans”.

This is an example of what the philosopher, Charles W. Mills, my former colleague at the University of Illinois at Chicago calls, “white ignorance”. He defines it as a historically constructed group-based cognitive tendency and moral disposition of non-knowing, of motivated irrationality. It is a perversely deforming outlook causally linked to white normativity and white privilege, in which white perception and categorisation, social memory and social amnesia are privileged, and non-white experiences and racial group interests are derogated.

White ignorance, Mills insists, is not confined to whites and is global in so far as the modern world was created by European imperialism and colonialism. It is a foundational miscognition that permeates perceptions, conceptions and theorisations in descriptive, popular and scholarly discourses. In his book, States of Denial, Stanley Cohen calls it “denial”, the willful act of not wanting to know, wearing blinders, turning a blind eye, blocking out, and of evading and avoiding unpleasant realities and horrific atrocities by the perpetrators and by bystanders of repression.

An often ignored site for the anti-racist struggle is the role of organised labour. In the US trade unions have declined precipitously. In the last four decades union membership fell by half from 20.1 per cent of workers in 1983 (17.7 million) to 10.3 per cent in 2019 (14.6 million). This helped reduce the capacity of the working class to organise against capital in the first instance, and to build multiracial coalitions and mobilise against the economic, political, and social system of racial capitalism. Deprived or divorced from collective class organisation and struggle, working people have been demobilised by capital and the political class. To be sure, in the United States the configurations of capital, labour, and politics have always been fractionalised, not least by the sheer scale of the demographics and ideologies of race.

As I noted in my earlier studies on labour movements after World War II, American trade unions at home and abroad were notoriously racist. However, the assault against organised labour accelerated in the post-civil rights era, as race was weaponised to camouflage the devaluation of labour under neo-liberalism. The “Southern Strategy” started peeling away white workers from the Democratic coalition. The rise of the “Reagan Democrats” culminated in the capture of demoralised and deradicalised white workers by Trump’s unabashedly racist insurgency.

In short, the anti-racist movement must find a way of mobilising the white working class, of aligning class, race, and gender for progressive change. More immediately, the labour movement, as Dave Jamieson notes, “faces a reckoning over police unions”. He notes that “police unions make a small slice of the AFL-CIO, but progressive members are increasingly uncomfortable associating with them”. Angered by police brutality, some labour leaders have called for cutting ties with police unions, increasing their transparency and accountability, and curtailing their funding and political power over both the Republican and Democratic parties.