On the night of April 9, 1906, a small congregation led by William J. Seymour, a black preacher, was meeting at a home on Bonnie Brae Street in Los Angeles, California. The group was three days into a ten-day fast, praying and waiting on God. Suddenly, “as though hit by a bolt of lightning, they were knocked from their chairs to the floor” and they began to speak in tongues and shout out loud praising God.

In the next few days, news of the event spread throughout the neighbourhood, and Seymour began to look for an alternative venue to accommodate his growing congregation. At one point, the front porch of the house collapsed under the weight of the swelling crowd. They found a place at 312 Azusa Street, a ramshackle building that had most recently served as a stable for horses with rooms upstairs for rent.

It was in this building on Azusa Street that the modern Pentecostal movement can trace its origins. People from all over the United States and beyond came to experience the “outpouring of the Holy Spirit”, and from the outset the Azusa Street movement was remarkable for attracting a diverse group of followers – black, white, Asian, people of all ages, income and class backgrounds.

Consider that this was happening in 1906 in “Jim Crow” America, just a decade after the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision that entrenched racial segregation as law in the US. The racial intermingling was a scandal, to some extent even more than the “Weird Babel of Tongues”, as a front-page headline from the Los Angeles Times described it. The paper continued: “Colored people and a sprinkling of whites compose the congregation, and night is made hideous in the neighborhood by the howlings of the worshippers, who spend hours swaying forth and back in a nerve racking (sic) attitude of prayer and supplication.”

Seymour’s mentor, Charles Parham (who was white), broke with his erstwhile disciple and was sharp in his criticism: “Men and women, white and black, knelt together or fell across one another; a white woman, perhaps of wealth and culture, could be seen thrown back in the arms of a big ‘buck n-gger,’ and held tightly thus as she shivered and shook in freak imitation of Pentecost. Horrible, awful shame!”

A few years earlier, Seymour had attended Parham’s bible school, which at the time violated Texas Jim Crow laws – Seymour had to take a seat just outside the classroom door. Later Parham and Seymour preached on street corners together, but Parham only allowed Seymour to preach to black people.

Seymour himself endorsed speaking in tongues as a sign of the Holy Spirit, but with time came to believe that although tongues-speech was the initial evidence, it was not the absolute evidence. He saw that some white people could speak in tongues and continue to treat people of colour as inferior to them. For Seymour, Holy Spirit tongues-speech had to be accompanied with a breaking down of racial barriers and a reordering of society – it had to be, as Ashon Crawley writes, a posture of protest: “It would have to be a practice that is not merely a style, but also a political practice.”

This stance was not unique to Seymour. Contrary to what today’s Pentecostalism may suggest, early Pentecostals – especially those who stayed close to Seymour’s position – rejected war, militarism, patriotic indoctrination, wage slavery and racism, believing that the love of Jesus had to supersede the love for nation-state, money, social class and yes, whiteness. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 (which came just eight years after the revival on Azusa Street) would put their convictions to the test. They opposed the war and refused to be drafted into the US military, arguing against it as conscientious objectors.

They were vilified for this, and called “traitors, slackers, cranks and weak-minded people for extending Jesus’ love beyond racial, ethnic and national boundaries”, as the seminal work, Early Pentecostals on Nonviolence and Social Justice, an edited collection of writings by those early leaders including Seymour himself, outlines.

Pentecostalism is mainstream now, so if you are thinking of a group that is radically committed to social justice and the breaking down of racial hierarchies and capitalistic exploitation, Pentecostals wouldn’t be the first folks who come to mind. But that obscuring of Pentecostalism’s early, radical history has made us all the poorer for it, and has resulted in reaching for prayer, speaking in tongues and public piety as the default, go-to reaction in the face of crisis. To be sure, early Pentecostals did pray, shout, jump, speak in unknown tongues and get slain in the Spirit. But they did more – their Spirit baptism had real-world, political consequences.

Seymour’s breaking ranks with his mentor Parham in some contexts is attributed to a difference in doctrine – Parham believed that tongues were real, translatable human languages, whose purpose was to empower missionaries to travel around the world converting non-believers to Christianity. Seymour believed that this could be the purpose of tongues, but that tongues could also be a “divine language”, perhaps the language of angels that could not be understood by human ears.

Pentecostalism is mainstream now, so if you are thinking of a group that is radically committed to social justice and the breaking down of racial hierarchies and capitalistic exploitation, Pentecostals wouldn’t be the first folks who come to mind.

Is it any wonder then that as a white man Parham’s understanding of tongues was embedded in a missionary-driven, evangelistic and imperial project, but Seymour – who as a black man could not even sit inside the very Bible school classroom teaching the concept of tongues – was convinced that the Holy Spirit had to bring a broader, more elevated freedom-speech that had the power to tear down the immediate racial restrictions in his own life?

In our context here in Africa, spirit-empowered movements were not necessarily a direct outgrowth of the Azusa Street revival. Some were, such as the Assemblies of God, Apostolic Church and Church of God in Christ, established by American Pentecostal denominations. But others either arose independently, and became known as African-initiated/ independent churches, or emerged out of Western mission churches as a revivalist streak within mainline denominations – Anglican, Presbyterian, Lutheran, Mennonite and so on. In later years another category emerged, that is the neo-Pentecostals, which became most associated with Pentecostalism as most of us know it today – the urban-centred, upbeat prosperity gospel churches.

“Good people” in positions of power

My own experience with Pentecostal and evangelical churches while growing up in middle-class Nairobi was one of not necessarily avoiding direct engagement with the political, but instead implicitly ascribing one of two theories of political change, if not both simultaneously.

The first theory assumed that concerns regarding social justice would resolve themselves spontaneously if the general population received the redemptive message of Christ and became Born-Again and Spirit-filled. It was a matter of simple arithmetic – individual salvation would eventually translate into societal transformation, one soul at a time.

This strategy may appear, at first glance, to be disengagement with the public sphere and with politics. However, as Damaris Parsitau’s research has demonstrated, African Pentecostals do not regard prayer, fasting and evangelism to be apolitical. Not at all. In fact, they are intensely political, a strategy that spiritually “takes the nation for Christ” through crusades, tent revivals, healing and deliverance services, conferences and symposia, fellowships, ladies’ meetings, men’s meetings, prayer fellowships and night vigils, and expects that this will eventually have real-world, political consequences.

The first theory assumed that concerns regarding social justice would resolve themselves spontaneously if the general population received the redemptive message of Christ and became Born-Again and Spirit-filled. It was a matter of simple arithmetic – individual salvation would eventually translate into societal transformation, one soul at a time.

The second theory of change is more targeted, and in some ways, more elitist. It is the idea that Christians can “infiltrate” and influence structures of power for good. In practice this means working to ascend to positions of influence in order to harness that power towards a “godly” agenda. This second strategy has become more refined in the neoliberal era, one that is ostensibly meritocratic, a “marketplace of ideas” where the best ideas and the most qualified people would rise to the top.

The mission was to ensure that these people, apart from being technically qualified for the job, would also be Born-Again, Bible-knowing, Spirit-filled and so “ambassadors” for Christ. It would also mean pastors and other religious leaders ascending to unofficial but incredibly influential positions as advisors to presidents and politicians, for example through organising “National Prayer Breakfasts” in Africa and elsewhere, which are usually attended top government officials.

Ebenezer Obadare’s Pentecostal Republic outlines how this latter strategy has played out to great effect in Nigeria since the country’s return to civilian rule in 1999. Obadare’s book makes a categorical assertion – that the Nigerian democratic process over the past two decades is ultimately inexplicable without the emergent power of Pentecostalism, “whether as manifested in the rising political influence of Pentecostal pastors, or in a commensurate popular tendency to view socio-political problems in spiritual terms”.

The problem with both of these political strategies, when we really think about it, is that both work with the general assumption that the fundamental political structures of society are either inconsequential to public welfare, or if they are, they are in the main, sound and just. They assume that all we need to fix racism, capitalistic exploitation, social decay, violence and neo-colonialism is first, a change of heart, and second, “good people” ascending to positions of power and influence. The system is mostly sound, the idea goes – all that is needed to fix it is “leadership”. However, these notions do nothing to radically challenge the status quo; rather they reify and stabilise it.

Slave patrols and modern-day policing

However, in the past few weeks, especially in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in the US, we have seen the limits of those arguments. Take the problem of police violence, for example. It is not a result of “a few bad apples”. Abuse, harassment, misconduct and brutality are not rare or aberrations; they are structural and part of everyday policing.

Policing in the African colony was always and inherently designed to protect the property of the elite – at first, European property and people, and later, the property of their African comprador successors. The African poor were viewed as a problem to be contained. The enforcement of minor offences designed to restrict African movement and corral them into working for European farms and industries took up most of the colony police’s time and resources. Even to this day, the first question that a Kenyan police officer is likely to ask you upon contact is for your ID card – a hangover from colonial vagrancy laws that still exist, which render the African as an “illegal” presence in the colony unless the African’s existence is justified – that is, if his/her labour benefits the colonial state.

The second theory of change is more targeted, and in some ways, more elitist. It is the idea that Christians can “infiltrate” and influence structures of power for good. In practice this means working to ascend to positions of influence in order to harness that power towards a “godly” agenda.

In the US, policing in the South started as slave patrols, first to capture runaway slaves and return them to their masters, and second to provide a form of organised terror that would deter enslaved people from revolting. Later, the police’s major job was to enforce the black codes of the Jim Crow South to control the lives and movements of black people. In the early 20th century in cities in the North, municipal police were primarily involved in suppressing and breaking up the labour strikes of the day.

In such a context, where impunity, classism and racism is the structure, the scaffolding and the raison d’être of the police force, how can one honestly say that you can “influence” it for good? Even the Jesus in the gospels did not move to Rome to “influence” Caesar; his life and ministry were instead in Judea, among peasants and fishermen.

Furthermore, oppressive regimes are sustained not by brute force alone, but also by a coterie of enablers who mistakenly believe that they can “change the system from the inside” but really only end up legitimising the regime. Using the context of Zimbabwe and the ruling party Zanu-PF, Alex T. Magaisa, in this article, expertly peels the layers off this fantasy that is frequently held sincerely by well-meaning and competent people, but which only ends up normalising the abnormal, and so becomes invaluable in giving a sheen of legitimacy to a thoroughly oppressive regime.

Magaisa’s searing analysis can apply to any illegitimate or repressive system in any country. “They may start from the periphery wearing the label of ‘technocrats’ but soon enough, they will find themselves deep in the cesspool, wearing scarfs and chanting ridiculous slogans…,” he writes. Cocktail parties and prayer breakfast meetings are not just about hobnobbing with the high and mighty; they also give the impression that everything is normal, which is something oppressive regimes desperately need. But as we say on social media, it always ends in premium tears.

In Obadare’s analysis, although Pentecostalism has indeed influenced the struggle for state power in Nigeria, it has had little effect on the state itself, “whether in terms of its governing philosophy or animating spirit”. In fact, Pentecostalism in Nigeria is a force focused on appropriating state power, and even demobilising civil society. Parsitau echoes this view. Her research highlights that in the Kenyan context, Pentecostal and Charismatic theology abstracts social evil into spiritual terms – attributing problems such as inequality, poverty and crime as the work of the devil, demons and other malevolent spiritual agents.

New sight, new tongues and a new wind

In my view, using simplified language like this is not necessarily a bad thing. Structural evil is sometimes so insidious and its effects so thorough that if you don’t have access to terms like “neoliberalism”, “the prison-industrial complex” or “exploitative capitalism”, the only way you can sincerely describe the devastation around you is to ascribe it to the devil.

It is actually demonic that the world’s richest 1 per cent have more than twice as much wealth as 6.9 billion people, or that the 22 richest men in the world have more wealth than all the women in Africa. How else can you describe our violent world where anti-blackness is global, where black lives are disposable, where women’s lives are the most precarious? How can you reckon with a planet that seems to be hurtling towards self-destruction? How can one exist in a world like that and remain sane?

In such a context, where impunity, classism and racism is the structure, the scaffolding and the raison d’être of the police force, how can one honestly say that you can “influence” it for good? Even the Jesus in the gospels did not move to Rome to “influence” Caesar; his life and ministry were instead in Judea, among peasants and fishermen.

Facing the truth – that fellow humans are, in fact, responsible for this state of affairs – is sometimes too much to contemplate. It would drive one to commit retributive mass murder, or resort to suicide. James Baldwin puts it thus: “To be a Negro in this country [the USA] and to be relatively conscious is to be in a rage almost all the time.” (We could say the same about being black anywhere in the world.)

Escapist though it may be, attributing such evil to the devil is, in some ways, a way of preserving one’s sense of humanity. Since I am human, surely those who commit such evil must be animated by a malevolent force, otherwise, how could we both be human?

But because Pentecost Sunday was recently held on 31 May, I want to argue, like Rev William J. Barber does, for a new Pentecost – and for revisiting the passions of early Pentecostal leaders and examine Pentecostalism in fresh ways. The account of the day of Pentecost in the New Testament, Acts 2, outlines a dramatic moment when Jesus’s followers spoke in new and unknown tongues, and were given new sight and power as a wind shook the building they were in. My dear friend Curtis Reed once told me that many Christians are exhausted by trying to identify and resist domination and intimidation because it is frequently housed in Christian language (like Deputy President William Ruto saying he’s “investing in heaven” when dishing out large sums of money to churches).

If we are to find that again in this moment, we need new sight (to clearly see the structures of domination) new tongues (language to describe what we are seeing) and a new wind (if whiteness is invisible and powerful like air, then Pentecost in 2020 would mean new energy and drive to confront these entrenched systems, just as we’ve seen a wind of consciousness drive a whole generation to the streets in Minneapolis, Atlanta, New York, London, and further still).

In my view, using simplified language like this is not necessarily a bad thing. Structural evil is sometimes so insidious and its effects so thorough that if you don’t have access to terms like “neoliberalism”, “the prison-industrial complex” or “exploitative capitalism”, the only way you can sincerely describe the devastation around you is to ascribe it to the devil.

The first thing the believers did after receiving the Spirit at the end of Acts 2 was to sell their possessions and share according to each one’s need, going against the logic and normative framework of Empire. (Empire is about extraction, accumulation, excess and wastage, as the early Jesus followers must have experienced intimately as oppressed subjects of the Roman Empire.)

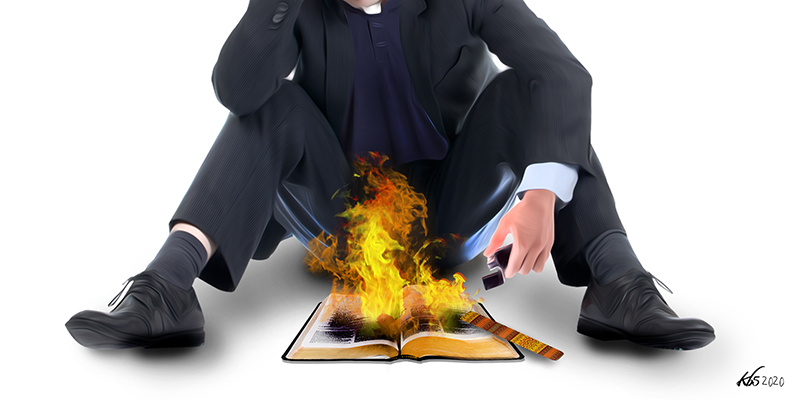

We must remember that the modern Pentecostal movement was led by a black preacher who saw that any claim of Holy Spirit baptism must have anti-racist and anti-imperialist real-world political consequences. This must lead us to move against patriotic indoctrination, militarism, and capitalistic excess. The love of Jesus and the power of the Spirit cannot be an abstraction, and cannot be limited to individual rehabilitation, but must extend into a practice of justice and equity for all people. It must be, as Seymour discovered, a posture of protest.