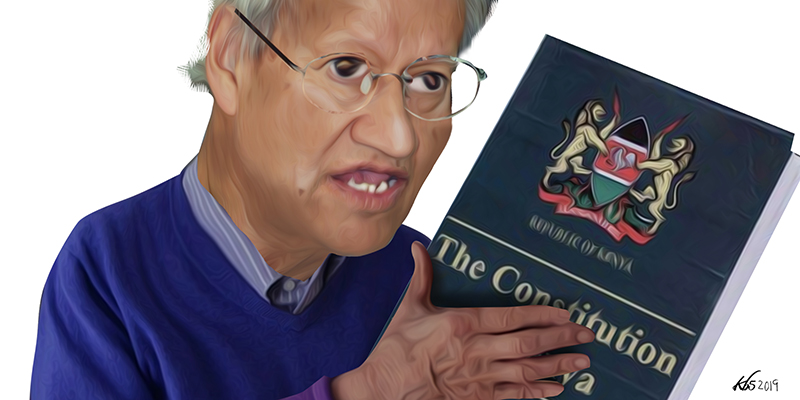

Over the course of his career, Professor Yash Pal Ghai has had the opportunity to act as a visiting professor in a number of countries, teaching law across Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, India, Singapore, South Africa, Canada, Fiji, and Italy. It was during one such visiting appointment in 2000, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, that Ghai received one of the most important calls of his career.

When the phone rang, Ghai was sitting with Bill Whitford, his longtime friend, in Whitford’s home in Madison. It was Amos Wako, Ghai’s former student, then the Attorney General of Kenya. “Come home,” Wako said to a stunned Ghai. His initial reaction was disbelief. “Are you really serious?” he asked Wako. “Yes,” Wako explained, “Everyone wants you to come home, and President Moi wants you to write the new constitution.”

Ghai’s initial reaction was, unsurprisingly, one of hesitation. “The government had never shown any interest in me, and I still felt bitter about the way I had been treated.” His hesitation was compounded by a feeling of detachment. Although he had been home sporadically in the intervening years, it was never for more than a few days at a time; he did not have a strong sense of what was happening politically. “I said no,” Ghai says. “I didn’t know what was happening, my experience had been bad and I didn’t know how sincere they were.” Indeed, Ghai had missed the years of political turmoil that preceded this moment. He had been away while the Kenyan executive gradually consolidated power and eroded democratic rights; he had missed the decades of struggle for constitutional reform.

Over the next few days, however, he consulted with old friends, including Pheroze Nowrojee and Willy Mutunga, who advised him to visit and survey the landscape before making a final decision. “Then one day my secretary rings from Hong Kong and says, ‘This man who rang has called again and wants to see you. Can I give him your details in America?’ The next day, Wako arrived in Wisconsin. He spent time with me and said things had changed and that I should give it a chance.” Cottrell Ghai also recalls it clearly. “Wako actually went to Madison. It was most extraordinary.”

As Ghai considered the offer, many of his contacts in Nairobi told him not to accept. The country was deeply divided, and the thinking around constitutional reform was concentrated in two opposing camps, one led by the Moi government and the other led by a coalition of religious leaders and civil society organisations, known as Ufungamano. Many in civil society did not trust that any real change could come through government-led efforts, and they believed that the focus should remain on deposing Moi from power. Mutunga was relatively alone among Ghai’s closest friends in his support. “He had written constitutions all over the place in the Commonwealth. He was honoured by the Queen for it. As a patriot, writing one for Kenya would be a great accolade. He had his doubts, but as a human rights activist we urged him to take up the task, notwithstanding the challenges.”

After some initial thought, Ghai agreed to visit Kenya and survey the landscape without necessarily committing. First, however, he had to return to Hong Kong, which he did via Papua New Guinea, where he had some work. Ghai was relatively cut off for the duration of his short assignment, but by the time he returned to Hong Kong, Wako had (falsely) announced that he had accepted the position, a move that would eventually come back to haunt Wako.

When Ghai made his first visit to Kenya in December 2000, it was a momentous occasion. Wako and Raila Odinga, who was at the time representing the Langata constituency in parliament, personally met and welcomed Ghai home. He used this initial visit to meet with key players and get the lay of the land, eventually deciding to take the position but only on his own terms. When he returned to Hong Kong, though, the University was unwilling to allow Ghai to accept the assignment. A few days after the refusal, Ghai received a call from the Chancellor. “He said he hadn’t been able to sleep,” Ghai remembers. “He had raised this with the Council and they said they felt a bit bad. After all, it was a chance for me to go back to my country. So they said, ‘Ok, but this is the last time you can go.’ We felt it wasn’t right for Jill to also leave so she stayed back.”

Whitford remembers Ghai’s hesitation. “He didn’t need that job. He just felt this tremendous loyalty to Kenya. He always travelled on a Kenyan passport even though he could’ve gotten a British passport. That was a real pain in the ass, but he did it. It was just important to him to play that role. It was about the chance to do something for his country.” Mutunga agrees, saying, “Kenya remained his constant North.” It had been more than three decades since Ghai had been a young student, standing on the steps of Lancaster House, watching the Kenyan delegates arrive to negotiate an independence constitution. This was a chance for him to contribute to the next phase of that mission – to lend the wisdom he had gained through years of service to other countries to his own homeland.

When Ghai returned to Nairobi, now ready to begin work in earnest, he was under no illusions. Moi was under pressure. He wanted someone who would get it done and get it done quickly. “I told Moi I wasn’t ready to accept. I would only take it if all the key groups in the country were involved in this process. I didn’t want to come and talk to a few politicians. I made it clear that it had to be a very participatory process. I said, ‘If you are willing on that basis, I will consider it.’ ” Ghai told Moi he required two to three months to merge the Ufungamano and government groups and create one united constitutional process. Ghai then embarked on what many consider to be one of his crowning achievements, the process of bringing the two sides together. So committed was he to achieving unity that he refused to take the oath as Chair of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) unless there was one, unified process.

In addition to the divisions between the government and Ufungamano, Ghai quickly found that he would also have to address divisions within the Ufungamano group itself. According to Zein Abubakar, who represented the Safina Party at Ufungamano and who also became a commissioner of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission, a “radical” wing of the Ufungamano process saw Ghai as someone who undermined the revolutionary path. Indeed, a radical minority group remained opposed throughout, branding those who participated as “sell outs.” At the same time, Abubakar explains, it was understandable; the government had never kept its word in the past and the fear of betrayal was very real.

Ghai was aware of the divisions. “At that time,” he remembers, “civil society were very divided about my coming. They had already formed their own commission. They had already started going from town to town to talk about the constitution. I didn’t want to sabotage them.” Indeed, John Githongo, who was the head of Transparency International at the time, remembers being highly suspicious of Ghai. “I’ll be very honest. I was very concerned and completely opposed to him. I’ve never told him this, but we were very, very skeptical of a person brought by Amos Wako, even though the Ghai brothers had a sterling reputation as academics. Yash was bright and super-brained, but our attitude was that there’s no way he’s going to get our politics. He’s been away too long.” Abubakar agrees, explaining that Ghai – despite his international reputation – had no legitimate standing with local civil society and religious leaders.

His commitment to achieving unity greatly impressed skeptics in the Ufungamano group. Abubakar says, “One of the things we appreciated was his position that there can only be one process, which was principled. One of the things that bothered a number of leaders was that if you had two processes, apart from divisiveness, how would you implement the outcome of either one? The country was split 55-45 in our favour. It’s very difficult to have a constitutional order that is not supported by half the country. There was also potential for violence and reversal of some of the democratic gains that people had paid for and won by then. At a strategic level, we said that it is better to negotiate a unified process.”

Ghai’s style, based on an objective and open attitude, impressed key players. Abubakar remembers, “The first thing he did was to listen to various sections of society and the listening process allowed him to understand that this process was deeply dividing the nation. Based on those initial consultations and listening, he decided not to take the oath as Chair. That also helped build bridges with the religious sector and the other side, because he was seen as credible and as someone who is not showing any bias. He was willing to listen to everyone who had an opinion.” Githongo agrees, pointing to Ghai’s refusal to take the oath as one of the key factors in shifting the tide in his favour. “His credibility started very low with progressive forces. He was seen as Moi’s man, Wako’s man. I remember all of us sitting around, discussing. People said, ‘No, no. This is a hatchet man for Moi, a waste of time.’ But then he refused to take the oath. Yash’s credibility was first built on that – his unwillingness to take the oath until the two sides came together. It was a very slick move, very well executed. In fact, he doesn’t talk about it or show it but he is a very politically wily operator. After that, all of a sudden, people took him seriously.”

Ghai also made it clear that he was willing to walk away from the process if it did not live up to his standards. Unlike many others who had been competing for the position of Chair of what would be the review commission, Ghai had no personal ambition to win the position. Abubakar says, “He was willing to walk away and that was important in terms of people’s willingness to sit and talk.”

Finally, Ghai’s connections to all sides greatly facilitated communication and eventual cohesion. “He opened back channels to government and to opposition leaders,” Abubakar says. “I think the insistence then of both Ghai and Raila supporting Ghai is what reluctantly convinced Moi to agree to a common process. If it had been Ghai alone, it wouldn’t have happened. It had to be Ghai and Raila. Ghai then said if there is no willingness to unite the country in a process and make sure the process is credible, he was willing to walk away.”

After nearly five months of negotiations, Ghai achieved unity. The two sides came together, and now the real work began.

As Chair of the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC), Ghai created and implemented a citizen-centred methodology based on his decades of experience. The CKRC set up local offices around the country, canvassing public views and educating Kenyan citizens about the process. The Commission also travelled extensively, in multiple rounds, to hold public hearings so that they could listen to what people wanted with regard to the key issues. It was important to Ghai to create a publicly-owned constitution, one that addressed people’s longstanding grievances and that offered equal empowerment and protection to all. He personally travelled to public hearings, further demonstrating his deep commitment to and investment in the work. Githongo says, “I was very impressed, and I grew to have a great fondness for him. He was not only giving intellectually. He believed deeply in the work.”

Indeed, the Ufungamano groups had already begun the process of canvassing public opinion, and Ghai was able to carry that initial momentum forward. “Many places were new to me,” Ghai remembers. “I had never been to so many places. In the beginning, it was not easy. My Swahili had deteriorated a lot, but I still enjoyed it and found it very interesting. I had never seen so many different Kenyans, different styles of dress and ways of life. I enjoyed getting people’s views, getting concrete feedback from the people.” Abubakar recalls Ghai’s personal touch on these journeys. “He has a willingness to learn from others, to talk to people, just ordinary people who flock around him. I had the occasion of him accompanying me to a number of public hearings. He has an ordinary touch with people. He has an ability to inspire people. He connects with young people, ordinary people, people from all different stations in life – from leaders all the way to people who don’t know where the next meal will come from. One time, we were driving to a hearing and he saw people walking on the side of the road. He said, ‘Stop the car and ask these people where they are going.’ They said they were going to the hearing. And then he asked for arrangements for them to be dropped there. And he’s in his element that way.”

The Commission was extremely successful, and by the end of the process, it had collected over 37,000 public submissions on a full range of issues. In its 2002 report to the country, the CKRC highlighted 13 main points from the people. Examples of these included a desire for a “decent life”, fair access to land, a request to have more control over decisions which affect daily life, leaders who meet a higher standard of intelligence and integrity, respectful police, gender equality, freedom of expression for minorities and accountable government. There was a clearly expressed demand to “bring government closer to us.” The CKRC was deeply moved by the public participation, commenting on how “humbling” it had been to see “people who, having so little, were most hospitable to the Commission teams, and [who were] prepared to raise their eyes from the daily struggle to participate with enthusiasm in the process of review.” Githongo calls this public consultation process the second pillar of Ghai’s credibility. “The process he defined and described helped people see that he was serious. He became a people’s hero.

Ghai’s commitment to his work generated massive amounts of attention. Abubakar says he respects Ghai for his ability to remain “down to earth.” He says, “Prof. [Ghai] didn’t take big security. The only time that he took it was when the government insisted and that was periodic.” This was in sharp contrast to other commissioners, who insisted on 4-wheel drive cars and who even refused to share vehicles with Secretariat staff. Mutunga agrees, recalling, “They wanted him to drive a big car; he refused. Moi even announced that Yash was being too lax about security, and we all thought it meant he would be bumped off! One of the reasons why he became so popular was because of his humility.”

At the end of public review, the CKRC moved on to drafting, producing a draft constitution in September 2002. Ghai then broke his team into thematic groups, each responsible for refining and improving specific portions of the draft. He called in experts from around the world to assist and offer comparative knowledge. He also courted diplomats, many of whom were so impressed that they offered to help fund the process. “But I said, ‘no,’” remembers Ghai. “I wanted it to be a Kenyan process.” Three days before the debate on the draft was to begin, however, President Moi dissolved parliament. Since all MPs were part of the National Constitutional Conference, the body legally mandated to adopt the new Constitution, things could not proceed. In December 2002, Kenya held landmark elections. Moi, who had been in power for nearly a quarter of a century (24 years), finally stepped down, ceding power to the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), headed by President Mwai Kibaki. One of NARC’s key campaign promises was the promulgation of a new constitution within the first 100 days in office. Once in office, Kibaki stalled. “When people talked about presidential and parliamentary systems, Kibaki used to say that we are opposed to an imperial presidency; we want a parliamentary system. Once he realised that he could be president, that all changed. There was a lot of this opportunism. Even Raila to a certain extent – once Raila realised he wouldn’t be president, he split away.” Indeed, speculation was rife that the aging Kibaki’s reluctance to move ahead with the Constitution was due, at least in part, to a provision that would prevent him from running for a second term.

In April 2003, four months after the elections, the process again got underway, this time at the Bomas of Kenya. Ghai remembers, “When we moved to Bomas, I told the people there that we are going to take over and we need six, seven months. This is going to be hundreds of people. I felt that people should have time to think about their own positions. The mood got better and better. People got to know each other. By the end, people who didn’t know each other had become good friends.” At the same time, however, there was increasing factionalisation amongst the delegates, each making decisions purely based on political self-interest. At one point, during a break in drafting, the government attempted to stop the process from continuing. “I don’t think I have ever seen him so apoplectic,” Githongo recalls with a smile. “Prof. started leading demos of delegates in the streets to demand entry into the Bomas, and that was against guys with guns and dogs,” recalls Abubakar.

Soon thereafter, Ghai was alerted that Kibaki was planning to take the CKRC to court and allege that the entire process was illegal. Upon hearing of the impending court case, Ghai moved quickly to finalise a draft. At this point, however, Ghai remembers that “the only people left in the constitution-making body were from Raila’s side. Others were told to boycott. Kibaki and the DP walked out ostentatiously at one point when they saw they wouldn’t get the vote they wanted.” Particularly contentious to the government were provisions for a parliamentary system and some aspects of devolution. He resolved to work hard to finish. “I had only ten or eleven days to finish and get an endorsement. We had to do so much so quickly, and that’s why some parts are not so good.” Kibaki succeeded in court, and the CKRC was prevented from passing its draft to the government. “That he was able to get the Bomas draft approved by the delegates before the reactionary forces disbanded the conference was a miracle,” says Mutunga.

Ghai returned to Hong Kong soon after finalising the Bomas draft. “I read in the papers that the High Court had declared the whole process and the constitution unconstitutional. I felt terrible. I think I issued a couple of strong articles saying that, based on the documents that started the process, we were legal. By that time, Kibaki had gotten enough support and bribed enough people. They dissolved parliament all together, and then there was nothing more for me to do.” Cottrell Ghai remembers the final push as particularly difficult. “They put huge pressure on the closing stages of the process. There was a sense of great satisfaction for having produced a document but he was disappointed.”

The government’s hijacking of the process became most clear at the end of the Bomas period, but Ghai faced enormous amounts of stress throughout the process. Cottrell Ghai remembers calling him every morning from Hong Kong, after reading the Kenyan papers online, to warn him about what he could expect that day.

Ghai had little say, for instance, regarding the team of commissioners he would lead, and it was clear that there were divisions. Some commissioners were little more than spies for the government side, sometimes purposely delaying progress, while others were more interested in using the opportunity for personal profit than for sincere constitutional reform. “After Yash had managed to unite the two sides, he found himself with a very difficult CKRC, riven with self-interest, corruption, people meeting with the president behind his back, people being paid off . . . which he had to mitigate on an ongoing basis,” says Githongo. Mistrust was so deeply embedded that Abubakar insisted on the verbatim recording of all meeting minutes. “It was the only protection against people who would change their views. Almost all our meetings were recorded verbatim with the exception of two to three of them, where it was so bad that people said to switch it off. Of course, that in itself was against what we had agreed.”

An early battle erupted over the Secretary of the Commission, who – according to both Abubakar and Ghai – was a severe alcoholic, incapable of discharging even the most basic of his duties. “The person was not fit for public office,” Abubakar remembers. When dismissal procedures started, however, Moi was against it, and he threatened to disband the entire CKRC. Ghai and others stood firm, making it clear that they were willing to walk away from the Commission if the Secretary was not dismissed. It worked. “It became so bad that when the other members realised that we were willing to disband, they backtracked and went to see Moi. They convinced him to give the Secretary a soft landing by appointing him to the Law Reform Commission,” Abubakar recalls.

Corruption and betrayal were significant issues, dogging Ghai throughout his time as head of the CKRC. Cottrell Ghai recalls this as a particular strain on Ghai. “Some of the commissioners were very nice, but others were lazy or corrupt. They were all a bit corrupt. That was all a big strain, constantly watching whether they were stealing. Yash would say, ‘I think I’m going to resign and then the next day, he would say, ‘It’s ok. I’ll carry on.’ The up and down was quite a strain.” Ghai agrees, attributing the onset of his diabetes to this period in his life.

Githongo also recalls Ghai’s stress and frustration. “Sometimes, he would rant and we would all sit and listen. And he would go on and on sometimes, talking about receipts and accounts, and then we would gently have to say, ‘Ok, let’s get back to the agenda.’ But he needed that outlet, that safe space to express himself.” Githongo explains that the kinds of problems he faced were new to him. “He is politically very savvy, but he had never functioned in a context where such avarice, corruption and greed were so blatant. It was even amongst people who were very respected legal scholars etc., and that seemed to really throw him. He was used to different types of problems.”

Abubakar remembers meetings in which members would try and build consensus around a certain issue. “Then you see a commissioner signal and leave the room. Then two or three people follow him. Then they would come back in and do a 180-degree turn on a position, or propose something that is inherently illegal. You could see from his facial expressions that he was angry, but there were few times when he would lose his temper. On a few occasions, he would just walk out of meetings.”

By the end, the process had taken a clear toll on Ghai. Recalls Githongo, “He has done some really difficult things. He has been in situations where guys would show up armed and he would have to negotiate with them to leave their AK-47s outside of the negotiation room. So he’s used to that, but this one is much more soul destroying. It’s avaricious, corrupt, deceitful and very money-oriented. That really threw him. He found himself interacting with some of the most respected law scholars, and he found himself completely stuck on issues like travel expenses. That took a toll. What was very clear to me is that Yash has not only put his whole mind and all his experience – which are both considerable – into this but he has put his whole heart into it. He would get very hurt by the betrayals, by the lies and by the realisation that he had been strung along.”

Ghai resigned in 2004, soon after returning to Hong Kong. Cottrell Ghai remembers being in Italy on vacation. “The internet was not that good. We had to use a dial-up connection, and after a lot of hassle he emailed his letter of resignation to the president from there.”

Despite all the challenges, Ghai does not regret accepting the job. “It meant a lot to me, especially because I had devoted a lot of my career to human rights.” He says that the chance to return home after having been “thrown out” was also significant. “In the long run, I feel it gave Kenya a new start. I don’t regret doing what I did. I met a lot of people, and I know so many more Kenyans than I would have otherwise known. It was really, really challenging, but I felt quite pleased in the end that I was able to bring some peace.”

There are still, however, elements that haunt him. “Our document was strongly parliamentary, and we were somewhat innovative about the role of the governor general in that context. I think people liked it. We were trying very hard to build a non-ethnic political system and many of those provisions are still in. I think a parliamentary system is better and more participatory; you have to be more careful as prime minister. Also, we hadn’t quite finished what we had wanted to do with devolution. I regret these two things very much indeed. The people who are now saying to change these elements are the ones who had not wanted it back then.”

In spite of the significant problems faced by Ghai and the CKRC, the Constitution of Kenya – finally promulgated in 2010 – is based largely on Ghai’s Bomas draft. For this reason, Ghai continues to be known as the “guru” and the “father” of the Constitution. One of his proudest achievements, and indeed one reason why the Constitution receives such widespread, international praise, is the Bill of Rights. “I am very proud of it,” Ghai says. “I think it’s a good document. It’s very people-oriented. There are a lot of methods through which they can take action, which they must be allowed to do. And I am particularly pleased about the Bill of Rights. If we are failing, it’s our fault. Our politicians have absolutely failed us, and now it’s up to us to solve it.”

Katiba Institute co-founder Waikwa Wanyoike agrees, describing the Bill of Rights as a personal reflection of Ghai’s thinking on human rights. Says Wanyoike, “He has a very strong connection to it. Even in terms of newer constitutions, I don’t think that we have any constitution that surpasses the Kenyan constitution, especially in terms of rights.” Wanyoike also credits Ghai for what he calls the uniquely “transformative” aspects of the Constitution. “What you get is an overthrow of the political order and the installation of a completely new political order which clearly spells out values and principles. That element of transformation is even more defining than any single chapter of the Constitution, and that was because of the design that he and the CKRC put in place, which was very, very participatory. It’s now very hard for the political class to try and trash what has been done.”

Mutunga agrees, especially with regard to the Bill of Rights. “Our Bill of Rights is the most modern in the world. It has borrowed from the progressive development of human rights from the world over . . . I am proud of it, too. In my writings I have called the jurisprudence envisioned by the Constitution ‘indigenous, rich, robust, progressive, decolonised, and de-imperialised.’ I see the constitution as rejecting and mediating the status quo that is unacceptable and unsustainable in its various provisions. If implemented, I have always argued, it could put the country in a social-democratic trajectory and act as a basis of further progressive social reform . . . if we have the political leadership committed to its implementation. It seems, however, that Kenyans as parents have given this ‘baby’ to a political leadership that cannot be trusted to grow and breathe life into it.”

Githongo also laments the nature of Kenya’s leaders, who he believes are incapable of implementing the Constitution with any sincerity. “On paper, our Bill of Rights is extremely progressive, but life is breathed into the Bill of Rights by leaders agreeing to be accountable and surprising their people by saying, ‘I can’t do this because it is wrong.’ Our guys make every effort to show that the Bill of Rights doesn’t apply to them. If you are poor, then you can die anytime; the Bill of Rights doesn’t apply to them. It hasn’t come to life for the majority of Kenyans.”

On the other hand, Githongo believes that Ghai’s work on the Constitution ensured that – despite everything – it continues to offer hope. He says, “We still have a hugely corrupt and dangerous elite that will do anything to continue looting and raping this country, but Yash wrote this Constitution so they can’t mess with certain things.”