On an otherwise ordinary Nairobi day in 2016, Yash Pal Ghai stood in a hallway of the Supreme Court of Kenya, waiting to have lunch with his former student and friend, Chief Justice Willy Mutunga. Ghai, carrying his usual striped cloth bag, its worn strap tied in a knot and its edges frayed, waited patiently, his unassuming nature belying his reputation as one of the world’s foremost experts in constitutional law.

Ghai soon noticed activity around the Chief Justice’s office. Mutunga had gone in, followed by several senior judges, many of whom had been Ghai’s students in the early days of Kenya’s independence. When he was finally called in, Ghai was taken aback by the arrangements in the room, which had been set up to swear him into the Roll of Advocates of Kenya. Mutunga had arranged it as a surprise.

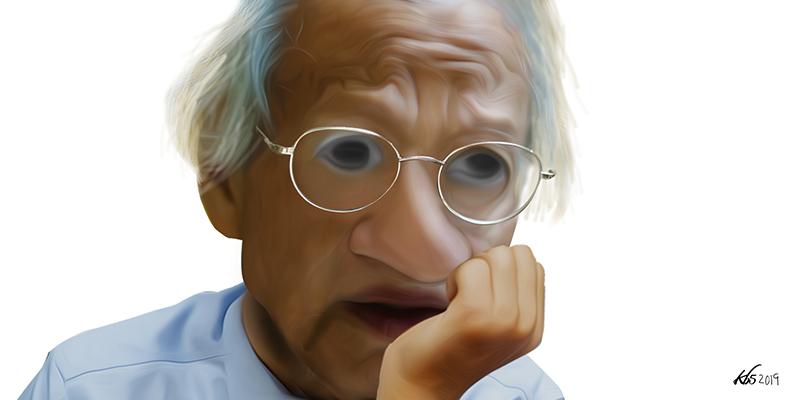

Now, at 78 years of age, and after having waited nearly half a century for this day, the father of the Constitution of Kenya – his small, slender frame concealed beneath a billowing, black robe and a white barrister’s wig hiding the silver wisps of his iconic, unruly hair – cut a distinctive figure in the room. “As Chief Justice, it was my singular and great honour to admit Yash in the Roll of Advocates on June 10, 2016, six days before I retired. I fought tears as I conducted this ceremony. It seemed like a culmination of brother-comrade-friend-teacher-student-patriot.”

It was a meaningful moment for Ghai as well, but – ever the professor – his memory of the day is dominated by pride in his student. “To see Willy, my former student, as Chief Justice, was very meaningful. I had kind of given up on practicing law at that point, so being sworn in was quite moving.”

It had been a long and circuitous journey, but Ghai was finally home. For Mutunga and many others, the moment was highly symbolic, a mark of rightful return, a sign that Ghai – whose lifelong work in the service of people’s rights had been done while in exile from his home – was finally back where he had always belonged.

Growing Up in Colonial Kenya

It may come as a surprise, given his long and illustrious career, but law was not Ghai’s first career choice. In fact, when he left Kenya for the University of Oxford in 1956, the young Ghai had been intent on studying English Literature. “I loved reading novels,” he remembers with a smile. “My father used to give me fifty shillings a month, and I would hoard it and hoard it until I could buy a Jane Austen novel. I thought I might be an English teacher.” When he wasn’t absorbed in an Austen novel – Pride and Prejudice being his favourite – young Ghai could be found with his best friend, Dushyant Singh, the son of esteemed High Court Judge Chanan Singh.

The youngest of six children, Ghai remembers a happy childhood. His family was close, and he was, in his own words, “slightly pampered” by his older siblings. Ghai’s home in Ruiru was behind his father’s store, Mulkraj Ghai Shops, a popular stop for the area’s coffee farmers. “We sold everything, from kerosene, to food, to general supplies. The farmers would come in the morning to place their orders, and by the time they returned in the evening my father would have prepared and packed each order.” Kenya in the 1940s was heavily segregated, and – aside from one notable exception – Ghai says he rarely saw a non-white customer. That exception was none other than Jomo Kenyatta. “At the time, Africans were not allowed to drink, but he used to drink a lot. He would come to the shop, and my father would take him up to our place, close the curtains and give him a drink. My mother would give them lunch. My father could have been jailed if anyone had ever known that.” Kenyatta, who developed a close friendship with Ghai’s father, took a special interest in the youngest Ghai. He would often ask to see the youngster, bringing him fruit from his farm. Ghai remembers seeing Kenyatta after he was released from prison. “When I had come home from Oxford, Kenyatta had just been released and he asked my father why he hadn’t taken me to visit him and my father told him that the queues of people waiting to see him were so interminably long! So he arranged for us to see him specially. There is a picture of us all together about a week after he was released.”

The success of his father’s shop blessed Ghai with a relatively easy childhood. He spent the week in Nairobi, where he went to school and was cared for by his grandmother, and returned to Ruiru on the weekends. His father emphasised the importance of education, and Ghai worked hard, excelling in school. In fact, when Princess Margaret visited Kenya in 1956, Ghai, as the top student in his school, was chosen to present her with a bouquet of flowers. Unbeknownst to him, it would be his first claim to fame. “In those days, the British had their own propaganda thing. There were huge, outdoor screens, and they would show these clips. It would start with news about the country, and then they would show a cowboy movie,” Mutunga laughingly remembers. “I saw Yash in that clip. That was the first time I saw him.” When asked about the moment, Ghai laughs quietly. “I fell in love with Princess Margaret.” Indeed, Mutunga says, “You know, the way the British did those documentaries was very, very interesting. A lot of us became monarchists as young kids after seeing those beautiful women and queens.”

The reality of segregated living meant that young Ghai had virtually no substantive interaction with the white, British population in Kenya. What little interaction he did have, though, showed the young Ghai how very different life was for some Kenyans. “We wouldn’t be allowed anywhere near any British home. We didn’t know any British kids.” In fact, as he now looks out over his garden in Muthaiga, Ghai describes his initial reluctance to live in the neighbourhood. “I remember dogs barking at me here. They would bark at any non-white person. I never wanted to be here.”

Most of the inter-racial interactions he did have in his youth occurred at school, especially during athletic competitions. Once a year, he remembers, the leading schools in Nairobi, each segregated by race, would have athletics competitions. “I took part in athletics. We would always lose, because the Prince of Wales School (for white students) had coaches and equipment. You were on the field together, but then at intervals you went back to your own side. We didn’t even get to know their names.”

Segregation was just one manifestation, however, of the harsh reality of inequality all around him. Ghai remembers witnessing insults and beatings on the streets. “As a kid, when I used to see people being beaten up, I couldn’t do much. The injustice of it left a very deep impression on me, the unfairness of it.” By the time Ghai was ready for university, he had been personally bruised by the harsh mark of racism as well.

As he was preparing to apply for university admission, Ghai was advised to seek assistance from the Ministry of Education. He recounts, “In the Ministry, I saw a lift and I had never been in one. So I got into the lift. I was about to go, and suddenly three white men came in and asked me what I was doing. They physically picked me up and threw me out, and I ended up on the floor. I was so shattered. I thought, ‘How can they just throw me like this?’ ” Taking the stairs instead, Ghai eventually reached the office of Mrs. Brotherton, who, Ghai had been told, could help with the university admissions process. “She asked me where I wanted to go. I said, ‘Oxford.’ She looked at me and smiled and said, ‘You? You want to go to Oxford?’ She laughed at me and then mentioned two or three other universities. ‘You really think you could go to Oxford?’ she taunted. I said that I wanted to try. She asked me if I had received a credit in my ‘O-levels.’ And I said, ‘No.’ She smiled and said, ‘See? You didn’t even get a credit in your exams.’ That’s when I said, ‘Madam, I did not get a credit. I got a distinction.’ She was so angry with me. She told me she didn’t think Oxford was good for me.”

It was a defining moment for Ghai, who had received the highest O-level results in Kenya. Instead of embittering him, however, the experience motivated him to forge ahead. In fact, when he spoke to his teachers at the newly opened Gandhi Academy, which would eventually become the University of Nairobi, they wrote to Queens College to recommend him. After passing the entrance exam, Ghai was accepted at Oxford. Given his intent to pursue literature, however, the university urged him to study Latin so that he would be prepared. “My teachers helped me get tutorials for Latin. They got this chap to come from the Prince of Wales School twice a week and tutor me. My school arranged it. I was quite pleased that this chap drove up and took the time. I thought, ‘He’s English but he’s quite nice.’ ”

Oxford (Queen’s College) welcomed Ghai, but it was an adjustment. “In the beginning, I was nervous in all kinds of ways – there were all these bright people, etc. I didn’t even know how to eat food British style. The British Council had set up a course on how to eat, and I attended that to learn how to use utensils. I would look at other people, and I got a complex about knowing which spoon to use.” Ghai quickly made friends, pursuing his love of sports and the outdoors. He also enjoyed time with his brother, who was still at Oxford, and with Singh, who was studying in Bristol. The two kept in touch, hitchhiking around Europe during their holidays.

Soon, however, Ghai realised that studying English literature was not what he had expected. “It was very difficult, because at Oxford they started four centuries before Austen. It was hard to read old English, and I just couldn’t cope. So I went to my tutor. He was understanding, and he asked me what I wanted to do instead of English. Even though my second love was history, I chose law.”

Ghai excelled at Oxford, so much so that, when he achieved the highest exam scores in the university, the College Provost told him that the College would henceforth take care of his fees. After graduating with his Bachelor’s degree in 1961, Ghai applied to undertake graduate work at Oxford’s Nuffield College. It was while at Nuffield, where he was studying comparative Commonwealth constitutions for his doctorate, that Ghai was approached by his former tutor. “He raised the idea of Harvard. I hadn’t really thought about it, but he said, ‘Why not take a break from Oxford and go to Harvard?’ He said I could come back later and finish my thesis. I wondered if the College would really allow something like that. He was such a nice person, and he wrote to his friends there. Harvard gave me a grant and a generous allowance.” At Harvard, Ghai completed a Masters in Law and also took courses related to his doctoral thesis.

And it was at Harvard that Ghai met William Twining, the son of the former Governor of Tanganyika, who would become a lifelong friend. Twining had just started a law school, along with AB Weston, in Dar es Salaam. The University of East Africa, as it was then known, was recruiting professors. “People were telling me that Twining was around and was looking for me. It turned out that he was looking for staff. When we met, he said, ‘I’ve come to pick you up.’ ‘Pick me up?’ I laughed it off.” Although he was tempted, Ghai was concerned about finishing his doctorate, especially because Nuffield had been so good to him. It turned out, however, that Twining had already spoken to Oxford and the university was very supportive, encouraging Ghai to take the position in Dar. “After a lot of thinking and consideration of the fact that this was the first time Africans would have had a chance to study law [in East Africa], I thought it would be good to do this. Twining had already recruited four or five teachers. I ended up going at short notice.” Although Ghai would continue to work on his doctoral thesis once in Dar, even publishing several chapters, he never had the chance to finish it. In 1992, the University of Oxford honoured Ghai with a “higher doctorate” in Civil Law. While ordinary doctorates are earned through a defined program of study, higher doctorates are awarded only through a nomination process and a review of a scholar’s research work over a period of time. Ghai is among only 96 recipients of this degree since 1923.

A Young Professor in Dar es Salaam

In 1963, Ghai, at only 25 years of age, accepted his first professional position as a lecturer of law at the University of East Africa at Dar es Salaam. It was a heady, idealistic time for the young graduate, as well as for the wider society. According to Professor Bill Whitford, Ghai’s colleague and lifelong friend, Dar was one of the most desirable places in terms of legal education at the time. “There was a wide range of people from all over the world, and the students were fantastic. The law school admitted only 100 students per year, and they were superb. The other thing was that this was [Tanzanian President Julius] Nyerere’s most creative period, and thoughts about creating a new society were all over the place. Everything was up for debate. It was a very hopeful time.”

Indeed, Ghai describes his time in Dar as “most formative” in terms of his professional growth; he was acutely aware of the significance of his role. “It was the first time black Africans were being allowed to study law [in Africa],” he remembers. “People didn’t know much about law other than that this is what the British used to beat you. We were aware that the students who left us could soon be judges or senior government officials, and we were conscious of inculcating in them the sense that law could be used for the promotion of good values.”

This conviction of his responsibility to inspire students to use the law to work for the betterment of society, to seize and channel the fervour of newfound independence in the direction of an equal, democratic post-colonial Africa, is partly responsible for Ghai’s break with the legal positivist tradition in which he had been trained, opting for what came to be known as “legal radicalism” or “law in context.” This approach, which sought to understand and interpret the law within the social, political and economic contexts in which it functioned, was not the norm at the time. In the new era of independence, however, Ghai and others like him believed it was critical for lawyers to understand how the existing law had come to be and how it might need to change to suit the rapidly evolving needs of newly independent nations. Writing about his years in Dar, Ghai says, “It was not long before I became acutely uncomfortable with endless explorations of the rules of privity and consideration, and became conscious of the unreality of the emphasis on the common law when it touched only a small segment of the population.”

Indeed, Mutunga credits Ghai for this approach. “We were taught law within its historical, socio-economic, cultural, and political contexts, thus departing from the conservative legal positivism with its clarion call that ‘law is the law is the law.’ We undertook to study, research, and practice law never in a vacuum. Above all, we anchored law in politics and shunned legal centralism. Our approaches were multi-disciplinary.” At the same time, however, Ghai ensured that his students were well grounded in traditional law. Mutunga describes the high standards Ghai held as a teacher, demanding that his students become masters of “staunch positivism” while having the skills to interrogate that tradition. Mutunga describes Ghai’s approach as a “fantastic balance,” recalling how his professor’s exams required students to address three questions dealing with technical aspects of the law and two questions asking students to critique the legal rules. “Dar law graduates could regard themselves as ‘learned,’ as we were distinguishable from other pretenders to the ‘learned’ tag.” Mutunga considered Dar to be his “liberation Mecca,” the place where he developed his own intellectual, ideological, and political positions.

Not everyone was a fan of this approach. Mutunga describes how some students were not interested in studying context. Already assured of high level jobs, these students “just wanted to know the rules so they could go out there and practice.” They were not interested in learning context. Some students wanted to “finish things and get marks. They had gone to law school to be ‘big people’.” Ghai himself has questioned legal radicalism, wondering if his students were at a disadvantage for not having trained as traditional lawyers. Mutunga, who adopted Ghai’s approach when he became a professor, disagrees, explaining that his own students have expressed how the approach of law in context helped them cultivate a more holistic approach to the law, and to an understanding of the law.

Ghai’s natural aptitude, not just for the law but also as an educator, quickly became clear. While teaching in Dar, he co-authored (with his colleague and friend, Patrick McAuslan) what would become one of his most well-known books, Public Law and Political Change in Kenya. Although his primary motive in writing the book was to provide a textbook for his students, who did not have authoritative texts on the laws of newly independent East Africa, Public Law became one of the most widely cited works related to Kenyan law. When it was published in 1970, Ghai was just 32 years old.

The authors wrote that they wished to provide an analysis and critique of Kenya’s development since early colonial times as seen through the processes of law:

We have never understood the function of the law teacher or writer to be the mere reciter of rules whose merit is to be gauged by the quantity of information he can relay. All African countries have great need for lawyers who can take their eyes off the books of rules, who can see more to law than a set of statutes and law reports . . . The law student must constantly be brought up against questions such as . . . what is this law designed to achieve, what set of beliefs lie at the back of this law . . . a text should aim to stimulate, even aggravate, not stupefy, and that is what we have tried to do here.

Their analysis was incisive and sometimes harsh, blatantly questioning, for instance, increasing executive power and the trampling of the Bill of Rights, which they said was so ineffective that they wondered why it remained a part of the Constitution at all.

George Kegoro, the Executive Director of the Kenya Human Rights Commission, refers to Public Law as “the bible,” and “easily the most widely cited book in Kenyan law.” Kegoro says, “At independence, everybody was trying to establish a frame of analysing Kenya and Kenyan society. How do you analyse society? What are the constituent components? He provides that within the book. There was no clarity about where the tails were, where the heads were. And what he did was to show us where the tails and heads were. It has held sway up to now. It is still very much a valued way of analysing Kenyan society, which is why the book gets cited over and over and over again. It is one of the reasons why he is a legend.” Kegoro pauses, then adds – with incredulity – “And he never talks about it himself! Ever, ever!”

In fact, despite his growing success, Ghai remained down-to-earth. He strove, in many ways, to be a peer of his students. “Yash belonged to a group of law professors and lecturers who did not carry the tag of ‘academic terrorists’. We reserved that tag for the faculty who clearly did not like to teach, did not like students, and suffered from egos and serious intellectual arrogance. Invariably, they treated us as intellectually inferior, adopted a pulpit lecture system where they ordered not to be interrupted while lecturing. Questions were to be asked during tutorials. Yash and others were different. They were approachable, treated us as equals in the word and spirit of the intellectual culture in Tanzania. “All students were Yash’s friends,” recalls Mutunga.

Indeed, Ghai’s ease with people placed him in the middle of a wide social circle, made up of students and colleagues. Despite his work, which was significant, Ghai invested time in creating and maintaining deep and often lifelong relationships with people around him. Mutunga explains, “He was always likable and great company in and out of class. Bear in mind Yash became a full professor at the tender age of 32. In all respects he wanted us to see him and treat him as a brother. Many of us were in our mid-20s. Today, whenever I communicate to Yash I sign off, Nduguyo/Your brother because of a relationship that spans almost over five decades.” Whitford describes Ghai’s ability to balance a social life with his professional duties. “He cooked, and he was an excellent cook! What male Asians cooked at that time?” Whitford asks in amazement. “He didn’t have servants, because he didn’t want to have that kind of relationship with anyone. He was a democratic socialist from the word ‘go.’ He entertained but was also very intellectual. It was typical to see him walking around with his arms full of papers all the time.”

Just as Dar es Salaam was a site where he flourished professionally, it was a place where home took on a new meaning. It was while in Dar that Ghai met and married his first wife, Karin Englund, who was from Sweden. Their daughter, Indira, was born in Dar in 1971. He remembers a pleasant life, with a house by the sea.

Ghai’s tenure in Dar was one of the most dynamic periods of his life. He quickly climbed the ranks, becoming the first East African dean of the University of East Africa’s law school in 1970. He was also personally approached by Tanzanian President Nyerere, who asked him for assistance in the development of the Tanzanian constitution. He admired Nyerere, who gave him complete freedom to say what he believed.

Interestingly, it was also while he was teaching in Dar that Ghai met his future wife, Jill Cottrell, for the first time. “I first met him in 1969. I was doing my Masters at Yale, and my supervisor had taught for a year in Dar. He knew Yash, who was at Yale on a short visit. My supervisor invited a group of people who had some connection to East Africa over for dinner, and then he invited me, although I didn’t know any of these people.” Cottrell Ghai laughs, remembering the evening. “He said, ‘I am going to introduce you to a glamorous man, but I think he’s going to get engaged.’ He did get married soon after that.”

Over time, however, the environment in Dar became increasingly stressful. In his reflections on this time, Ghai writes of more and more racism. “For despite the scholarly analysis of some Marxists, what passed in general for radicalism in those days included a large amount of racism and xenophobia. I remember overhearing the wife of a Tanzanian colleague – a self-proclaimed Marxist – that she would not rest in peace unless she saw that muhindi (Indian) out of the country – that muhindi being me!” In fact, a growing drive to “Africanise” things, along with the University of Nairobi’s continued and persistent invitations to return to Kenya and assume the deanship at the law school, tempted Ghai to finally accept the offer.

Disclaimer: This article is meant as a brief overview of Professor Yash Pal Ghai’s life and career. While it aims to shed light on some of his personal and professional experiences, it is not a comprehensive account.