In addition to loans, both external and internal, plus arrears owed to suppliers (known as domestic arrears), Uganda’s debt burden is being augmented by a steadily increasing stream of court awards against the government. The judgment debt comprises awards and compensation for state-inflicted violence, unlawful occupation of property by the armed forces and others, non-payment for services and using services with the full knowledge that the government is unable to pay for them.

Indications are that in addition to aggressive new taxation policies (e.g. the taxes on digital cash transfers and social media use), the Ugandan government has been dealing with its financially precarious position by withholding payment for goods and services supplied. However, this ends up costing more in the long run when suppliers file suits and are awarded damages with interest.

Judgment debt arrears (not to be confused with domestic debt arrears) go back many years and had reached UGX648 billion (US$170 million) by July 2016. The Treasury releases UGX4 billion a month to be shared out among claimants prioritised according to a formula devised by the Ministry of Justice. Because much of the judgment debt is awarded with interest, the longer government takes to pay, the greater the debt.

At the end of the day, the biggest loser to government corruption and incompetence is the smallholder farmer who is also the largest contributor to Uganda’s hard currency earnings. Smallholder-produced coffee is still Uganda’s leading foreign currency earner. Yet farmers are the most negatively impacted by the government’s failure to provide appropriate agricultural interventions, such as advisory support and post-harvest technologies.

The lawsuits against the state arise from two main sources; criminality and incompetence. The criminality includes multiple unlawful seizures of property from citizens both officially and by officials for their own benefit. Vehicles are also unlawfully impounded by the police. Compensation for the victims of police and army brutality, including torture, robbery, shooting, unlawful detention and malicious prosecution, accounts for 32% of the judgment debt arrears. The debt will grow as land grabs and state violence increase and the perpetrators continue to enjoy the support of “development” partners, such as DfID (UK), Danida (Denmark), Sida (Sweden), Norad (Norway), Ireland, Austria, USAID, IFAD, the Africa Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, among others.

At the end of the day, the biggest loser to government corruption and incompetence is the smallholder farmer who is also the largest contributor to Uganda’s hard currency earnings. Smallholder-produced coffee is still Uganda’s leading foreign currency earner. Yet farmers are the most negatively impacted by the government’s failure to provide appropriate agricultural interventions, such as advisory support and post-harvest technologies.

Some of the awards reflect the times in which we live: land has been appropriated for the settlement of refugees and for use by UN peacekeepers. State crimes have included armed robbery and theft by the armed forces and slave trafficking of women to Iraq by Uganda Veterans Development Ltd, a company set up to help army veterans. There are law suits for breach of contract caused by procurements gone wrong — the Standard Gauge Railway suit was shelved but the eventual settlement will still be a cost to the public.

Authenticity issues

Incompetence has given rise to many cases of breach of contract. The fact that goods and services are still bought on credit can only mean that if procedures are being followed, either Treasury releases of cash are diverted or that government business cannot continue within the IMF–approved resource envelope and accounting officers continue to rely on credit knowing it cannot be repaid.

Much of the judgment debt is for non–payment for goods and services on the grounds of insufficient funds i.e. it comes from domestic arrears. Therefore, existing domestic arrears are potential judgment debts if the suppliers sue. Domestic arrears payable to suppliers stand at UGX1 trillion (US$267 million).

This writer has covered the debt industry elsewhere (also known as “air supply”). Suffice it is to say here, just as the burgeoning salary arrears in the 1990s pointed to the payroll ghost employees industry, so escalating domestic arrears suggest an element of fraud. It has been found in the past that fictitious billings and other claims can be made and are approved for payment by colluding officials who then share the proceeds with the “supplier”. Therefore, domestic arrears need to be verified by an audit.

It is arguable that for Parliament to regularise illegitimate debt – debt incurred with the knowledge that funds for repayment are unlikely to be found – with supplementary budgets is unconstitutional as it defeats the whole purpose of the budget process. Meanwhile, amounts awarded against the government in new judgments continue to escalate. This is partly due to the increase in land-grabbing cases for which compensation is high. The Ministry of Justice states: “UGX249bn in FY 2012/13 to over UGX.865bn at the end of FY 2015/16. The contingent liability of Government against uncompleted civil matters (ongoing cases) is estimated at UGX.4.2 Trillion.”

According to a manual record seen, the total provision for claims for the period 2011–2013 was US$9,168,111,441. These are US dollar expenses incurred by suppliers. (Note that since the first draft of this article in April this year, the shilling has fallen against the dollar from 1:3,696 to 1:3,819, increasing the dollar debt by UGX1,127,677,707,243 in just four months.) It is unclear if these figures include the US$10 billion judgment of the International Court of Justice awarded against Uganda for the unlawful invasion and subsequent looting and pillaging of Eastern Congo by the Ugandan army. The ICJ debt is greater than the US$8 billion owed on loans.

The Treasury has made some changes in 2018. For example, rather than the Ministry of Justice being responsible for the payment of awards, the responsibility has been decentralised so that the ministry, department or agency (MDA) committing the offense must cover it from its own budget. That means the MDA must estimate the likelihood of such eventualities and manage staff and finances in a manner that reduces the likelihood of successful claims against it.

Additionally, legal reform has made arbitration compulsory. This means that claimants must now attempt to reach an agreement with the government before filing a suit. The process can take years. While this makes sense for contractual breaches, it may not sit well with victims of, say, unlawful eviction, land theft, trafficking and police brutality who may need quicker relief and want their day in court. Close to half of the awards arising in the years 2011–2013 were against the police and army. Fourteen per cent are land-related.

The state could go further and pin accountability on individual employees. Offending officials and support staff could be made to contribute to awards from their pensions and gratuities.

Mismanagement of the agricultural sector

What we learn from scrutinising judgment debt and domestic arrears is that debt generally must not be considered in isolation from the need for competence in public administration. Poor planning, abdication of responsibility to foreign entities and the lack of accountability are behind the need to borrow even for day-to-day government business. They drive soaring judgment debt and staggering levels of domestic arrears. The management of the agricultural sector, the backbone of the economy, serves as a good example.

Not unlike the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) debacle that cost the government a loan of US$54 million and co-financing from the International Fund for Agricultural Development and other donors of US$52 million, a Ministry of Agriculture milk programme ended in tears for some, massive financial loss to the state, and swirling suspicions about corruption.

Under the milk scheme, the farmers of Fort Portal, Bundibugyo (80% of the local population) and nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo were allocated two cooling plants by the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Industries. One was located in Ntoroko, a good one and a half to two hours of off-road driving from the milk producers of Fort Portal and Bundibugyo.

Not unlike the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) debacle that cost the government a loan of US$54 million and co-financing from the International Fund for Agricultural Development and other donors of US$52 million, a Ministry of Agriculture milk programme ended in tears for some, massive financial loss to the state, and swirling suspicions about corruption.

It may have been that the objective was to provide a source of income for this new district, but when visited by Uganda Radio Network reporters in 2008, the Ntoroko chiller, pasteuriser, packaging machine and generator seemed never to have been used and were covered in dust, cobwebs and rust. Some farmers interviewed were unaware that there was such a thing as a milk processing plant in Ntoroko. The consensus among producers was that the plant was too far. Milk was normally transported in small quantities by bicycle or ordinary pick-up trucks to Karugutu Trading Centre on the Fort Portal-Bundibugyo highway where it was sold.

The district agricultural officer of Ntoroko denied claims regarding the inappropriate location giving the reason for the plant’s falling to disuse as the “laziness” of the farmers who were unwilling to travel to Ntoroko.

Two suppliers of milk processing equipment, Capital Venture International Ltd and Charm Uganda Ltd, eventually sued the government for expenses they incurred in storing and securing 34 coolers for a protracted period while the equipment remained idle. The record shows claims of US$405,448 and US$383,273, respectively. UGX 2,366,163,000 in total were provided for the claims. The farmers, meanwhile, were still being left stuck with extra unsold milk for lack of buyers with cooling facilities. (Buyers will not buy milk they cannot sell immediately or preserve).

It was left to the Catholic Church to intervene in Masaka. The Catholic Diocesan Development Organisation (Maddo) established a milk collection centre at Kirimya on the outskirts of Masaka town, one of six such centres planned. In 2014, the government of the Netherlands supported the Uganda Crane Creameries Cooperative Union (in Ankole and Kigezi) by providing half the cost of cooling equipment so that farmers providing the other half could test milk quality in laboratories and chill and otherwise manage their product without being beholden to processing plants that underpaid them. In 2016 a foreign investor installed a milk processing plant worth US$13 million in Kiruhura, Western region.

Corruption was proved in the case of the government intervention. The government’s activities in milk production have yet to be comprehensively probed. In their report on NAADS, the World Bank suggested it was a potentially workable scheme derailed by interference from the President. He allegedly transformed an advisory service into a farm inputs give-away scheme (Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) report on NAADS, March 22, 2011). The main beneficiaries turned out to be the elite and not the poor farmers it was intended to assist (“elite capture”). After the project, the evaluation team found only “negligible” improvements in farming operations and gave it an overall “moderately unsatisfactory” rating.

Despite the shortage of cash for development, give-aways continue. President Museveni’s latest in the agricultural sector is to one Dr. Ahmed Eltigani Al Mansourie, an Emirati who is about to demonstrate how a single heifer can produce 50 high-yield milk calves. He has been given 27 square miles of Ugandan territory for free on which this feat is to be performed. Post-demonstration, it is unclear to whom the livestock and the land will belong. In the State of the Nation address of 2018, the youth were invited to approach “us” for grain milling equipment. It is pledges such as these that undermine financial planning and give rise to debt.

Another intervention in the agricultural sector was the provision of rice hulling facilities. The supplier, Charm Uganda, sued for non-payment. In addition to the balance on the price, the firm was awarded UGX50 million in damages – money that could have gone towards improving the lives of farmers.

It does not augur well for the economy that the Ministry of Agriculture is a major serial offender. It has been sued for non-payment for construction of various infrastructure, such as a fish landing site, livestock markets and valley tanks.

The scale of non-payment of suppliers means either the budget is not fully funded and the government cannot function without credit or sharp practice, or that funds provided are diverted from their approved purpose. Or both.

The competence or otherwise of World Bank project designers and planners is also at issue here; critical errors were made in restructuring the agricultural sector. While planning to retrench the government’s agricultural support staff, the Bank planned to retrain them to deliver extension services privately. Although critical to the project’s success, the training did not take place as planned. The project also resulted in shortages of experienced extension staff.

The competence or otherwise of World Bank project designers and planners is also at issue here; critical errors were made in restructuring the agricultural sector.

Robbing smallholder farmers is a continuing tradition

The sale of the Dairy Corporation and other state enterprises continued the tradition of exploitation of smallholder farmers. It began when the colonial administration had a statutory monopoly on buying export commodities. A percentage of cotton and coffee sales was retained by the colonial administration. Farmers also paid export taxes levied on cotton and coffee, poll tax and other taxes. Farmers’ withheld earnings were purportedly insurance or enforced savings. They were supposed to be shared out among farmers during the years when the international price for the commodities fell.

In reality, the money was used to run the colonial administration, to build infrastructure and to bail Britain out before, during and after the Second World War. Britain held deposits of commodity assistance (also called price stabilisation) funds belonging to the colonies of as much as £1,200 million in 1957. They would have earned interest on those sums. (John Stonehouse MP, Commonwealth and Empire Resources debate, House of Commons, 1957).

So abundant were cotton and coffee revenues that the government was able to borrow against them to build the Nalubaale Dam and to service the loan. In 1955 the Uganda Coffee Price Assistance Fund stood at £15 million and the Cotton Price Assistance Fund at £20 million (the dam cost less than 15 million). Withdrawals of the funds for development required individual colonies to submit project proposals to the Colonial Office.

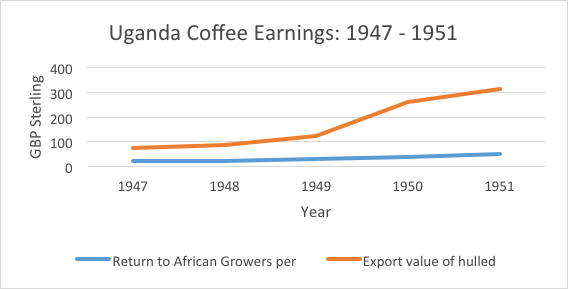

Smallholders continued to subsidise the government even after independence as the government maintained the monopoly on buying and exporting commodities. The revenues continued to be the major source of government finance. The monopoly was only abolished in the 1991 when production was no longer profitable and was being abandoned by farmers. The goose that laid the golden egg was finally dying. Below is a snapshot of the difference skimmed off farmers’ earnings.

Data source: Mukherjee. R, Uganda, an Historical Accident?: Class, Nation, State Formation, 1985

Parastatals paid for with some of the farmers’ compulsory savings (shown in the above chart) have been sold by the state, leaving the sector with inadequate post-harvest facilities. The promised greater efficiency and broader service delivery have not materialised. The outcome of the privatisation of the Uganda Electricity Board, which resulted in higher subsidies being paid to the sector than before, puts paid to any lingering illusions about the benefits of divestiture under the structural adjustment programme.

Meanwhile, the latest available World Bank statistics show that undernourishment in Uganda is on an upward trend, having increased by 13 percentage points between 2006 and 2015. In the Kenya, Tanzania and Rwanda, where there is significant undernourishment, at least the percentage is slowly going down.

At the same time, Uganda’s farming population is now being encouraged to move to as yet non-existent urban areas. “The main growth will come by expanding the middle stratum of commercial farmers from the current 10% to 65% […] and reducing the smallholders from 85% to 25% by 2040.” (Uganda National Coffee Strategy 2040 Plan for 2015/16)

President Yoweri Museveni has been clear on his attitude towards smallholders: “One of the characteristics of backwardness is to have more people in agriculture than in services.” He also asked heads of urban areas to promote and support industrialisation […] for wealth creation. […] establishment of factories will be facilitated by development of infrastructure.”

President Yoweri Museveni has been clear on his attitude towards smallholders: “One of the characteristics of backwardness is to have more people in agriculture than in services.” He also asked heads of urban areas to promote and support industrialisation […] for wealth creation. […] establishment of factories will be facilitated by development of infrastructure.”

The plan is to consolidate smallholdings to large, modern, commercial and most likely foreign-owned GMO farms because, to use the latest catch-phrase, what the economy needs is “farmers” not “diggers”. Could it be that the government has finally given up on the 80% of Ugandans who live in rural areas?