“That old law about ‘an eye for an eye’ leaves everybody blind. The time is always right to do the right thing.” – Martin Luther King Jr

When my colleagues and I at the Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU) learnt about the disappearance in June 2016 of our comrade advocate Willie Kimani, his client and their taxi driver while in police custody, our hearts sank.

We knew without doubt that the chances of finding them alive, leave alone finding their bodies for a decent burial, were slim at best. Unfortunately, many Kenyans and friends of Kenya who followed the unfolding drama did not share our fears. They held on to the hope that the three would still be found alive and well.

Apparently, Willie and his colleagues seem to have shared our fear, as we came to learn later from the SOS note he sent from the container cell at Syokimau Police Post before they were bludgeoned to death. This is the tragedy of policing in Kenya, where hundreds of citizens, mainly young men, have been victims of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial executions at the hands of law enforcement agencies over the past decade. They have disappeared or been executed mainly because authorities have labelled them criminal suspects ‘who deserve to die.’ In the process many innocent lives have been lost through the actions of those mandated to uphold the law.

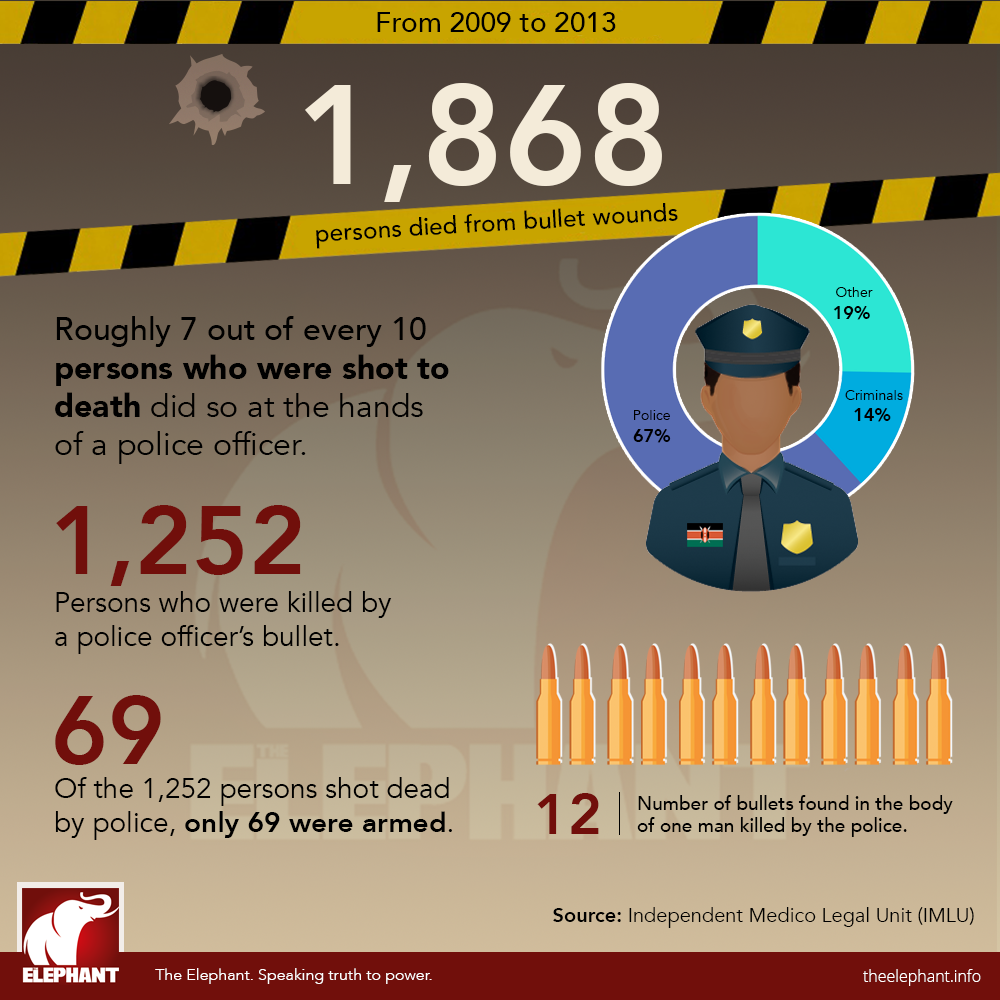

Various research studies and surveys in the past few years indicate a deep, systemic problem that has spiralled out of control. According to research by the IMLU conducted in seven major government morgues in the Kenya covering a five year period (2009-2013)[1] a total of 1,868 persons had died from bullets, 67% (1,252) of them having been killed by police officers and only 14% by criminals. Of the total who had died from police bullets, a worrying 67.7% (1,264) were killed by police in unclear circumstances, with one unique police killing where the corpse had a total of 12 bullets. Only 69 or 3.7% of the 1,252 shot dead by police were armed, putting into question the main reason given by police to shoot to kill. Though this report received widespread media coverage[2] and wide support from various stakeholders who called for immediate action to remedy the situation, it received strong condemnation and denial by the National Police Service, with their spokesperson Zipporah Mboroki saying, “Those people [IMLU] have only found the research they want to find. They have their statistics and we have our own.”[3]

Denial Has Become Standard Practice

Unfortunately this state of denial has become standard practice – a practice of sheer unaccountability since various demands by the media, CSOs and other stakeholders have yielded no fruit, with police having failed to provide official statistics of civilians killed by police whether legally or extrajudicially.

Indeed, the annual police Crime Statistics have year in year out failed to include numbers of police officers involved in crime. There are allegations that this information while available in the draft reports by the National Crime Research Centre is always deleted from the final report at the behest of the police high command.

The tragedy of our nation is that this problem is bigger than police violence, with many media reports of brutal spousal violence and mob killings of criminal suspects, and thousands of cases of unreported violence, threats of violence and brutalisation of residents of poor urban neighbourhoods by criminal gangs and police officers

Four years after the June 2014 IMLU report, this trend continues with IMLU’s daily vigilance reports reporting a total of 489 civilian killings by police for 2014-2016 (186 in 2014; 126 in 2015; 144 in 2016) and 33 for first three months of 2017. Of the total, over 80% were extrajudicial executions. Reports from other organisations including the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch indicate the situation is deteriorating.

The tragedy of our nation is that this problem is bigger than police violence, with many media reports of brutal spousal violence and mob killings of criminal suspects, and thousands of cases of unreported violence, threats of violence and brutalisation of residents of poor urban neighbourhoods by criminal gangs and police officers who patrol the narrow paths that crisscross these areas.

Various studies including IMLU’s 2015 collaborative research with Dignity and University of Edinburg on urban violence in poor urban neighbourhoods[4] showed that 25% of the 500 respondents had suffered various forms of violence in the previous 12 months. What shocked the researchers was that most of the violence was inflicted on victims within the household, by organised criminal gangs at 46% followed closely by the police at 26%! This is the scenario that applies to many rural and urban neighbourhoods where criminal gangs and police rampage, terrorise, intimidate and instil fear into people’s lives, leading to a growing acceptance of the police ‘tough on crime’ policy that has now metamorphosed into police officers’ illegal use of firearms, shoot-to-kill on sight, strangulations, torture and bludgeoning to death, abduction and enforced disappearances.

In one of the latest cases, in Eastleigh in Nairobi on March 30 2017, residents including business leaders who were willing to speak openly dismissed those protesting against the police executions as non-residents who did not know what residents in Eastleigh were experiencing. Just days after this, the media[5] reported that AP officers in Utawala area in Nairobi had stopped and shot dead the son of a Senior Superintendent of Police who had been sent by his mother to buy meat at the nearby shopping centre. According to media accounts the young man was forced to sit down and shot eight times as he pleaded that he was the son of a police officer and was headed to the shops.

Again, on April 20 2017, police shot yet another young man, this time a deaf teenager who witness accounts indicate was rummaging for items to sell from Nairobi’s largest dumpsite when a police officer called out to him. Being deaf and therefore unable to hear and respond to the call, the officer shot him in cold blood and claimed he was an armed suspect ‘who deserved to die.’ And the story of the killings goes on and on ….every day!

Acceptance of extra-judicial executions is a licence for every poor soul who feels aggrieved and is unable to rise above the grievance and provide a rational solution to it, to bludgeon their next door neighbour to death

Acceptance of extra-judicial executions is a licence for every poor soul who feels aggrieved and is unable to rise above the grievance and provide a rational solution to it, to bludgeon their next door neighbour to death for one transgression or the other, since we have suspended the rule of law that is the essence of democracy.

The Culture of Violence Is a Deadly Panadol

The culture of violence has been proven unproductive in the medium and long term – just a temporary relief, a Panadol to soothe the pain, but disastrous in the long run. It has been argued in this country before that the late John Michuki, the one of ‘rattling the snake’ fame, was successful as National Security Minister because he ‘finished off’ the Mungiki menace by authorising the mass murders of the sect’s members, especially in his backyard of Murang’a County. But we forget that the Mungiki thrived in the first place because they had been embraced as useful tool in politics during the last days of the Kanu era and the initial years of the post-Kanu era, as the errand boys of the powers that be. We also know that the mass killings only led to a temporary ceasefire and the metamorphosing of the gang into other forms, as we witness today

These are just two of many situations that are an illustration of what can go wrong when we set aside the rule of law and embrace the Hobbesian state where life is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.’ If this is what we yearn for when we become cheerleaders for systemically rogue police actions, then Hobbes warns us that we must be prepared for the consequences: ‘Where every man is enemy to every man; and wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them with.’

When we give licence to police officers to depart from the dictates of the Constitution of Kenya 2010 that envisages a National Police Service that ‘strives for the highest standards of professionalism and discipline among its members; to prevent corruption and promote and practise transparency and accountability; comply with constitutional standards of human rights and fundamental freedoms, we give them a licence to become criminals accountable to nobody but themselves!

‘Apart from the existence of crime that has led the public to acquiesce to police impunity there are other major factors that have led us where we are today.’

Among the first ones is the paralysis in police reforms since the 1960s when the first police reform initiative was made to the latest and boldest attempt through the Constitution of Kenya 2010. The National Police Service Commission mandated to clean up and professionalise the Police Service through a transitional vetting process has excelled not only in failing to execute its own mandate but in happily watching as that mandate is whittled down by the Executive through legislation without even a whimper from its end. The Commission allowed over 20,000 new officers to be recruited without following the Recruitment Regulations the Commission has developed and gazetted, and been unable to play its rightful role in reviewing and approving promotions recommended by the Service Board.

It has been argued in this country before that the late John Michuki was successful as National Security Minister because he ‘finished off’ the Mungiki menace by authorising the mass murders of the sect’s members. But we forget that the Mungiki thrived in the first place because they had been embraced as useful tool in politics

Having received many public and CSO submissions on human-rights violations by individual officers and spent over Ksh300 million on the vetting process, there is nothing to show with regard to ridding the service of human-rights violators. In fact, some of the senior officers about whom complaints were received on human-rights violations have ended up placed in charge of the formation of new recruits or at other senior policy making levels! No wonder then that even with over 40,000 new officers appointed in the past four years of the current government, we have yet to see a change of attitude and behaviour among the rank and file. Three years into the vetting process, no single officer has been dismissed from the force or prosecuted on account of human-rights violations, a situation that has deeply frustrated the many victims and families who have submitted their complaints. The vetting process has become so opaque that the country must take a decisive and immediate step to stop this circus going on for any longer.

Where Are the County Policing Authorities?

The other main factor driving these atrocities is the dire absence of leadership at the ministerial level when it comes to denouncing those involved in criminal activity, with ministry officials and the Cabinet secretary mainly in support of deploying more hardware and tough crime policies that do nothing to bring about a meaningful change of behaviour and attitude among the police or promote public participation and partnerships in policing, two key ingredients towards lasting public safety and security.

Four years after the enactment of the national Police Service Act 2011 and the setting up of county governments, the ministry has failed to gazette regulations to guide the establishment of County Policing Authorities and key platforms for public-police co-operation in crime prevention and response. Instead, ad hoc measures like Nyumba Kumi that are neither anchored in policy nor in law continue to be implemented with minimal exchequer support. Other reforms like transferring authority to incur expenditure to Officers Commanding Police Stations who are in charge of operations continue to face resistance from the police high command, leaving operations with minimal resources like fuel for effective crime prevention and response capacities.

The National Police Service Commission mandated to clean up and professionalise the Police Service through a transitional vetting process has excelled not only in failing to execute its own mandate but in happily watching as that mandate is whittled down through legislation

On the other hand, independent police oversight mechanisms like the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (IPOA) and the police Internal Affairs Unit (IAU) continue to face major challenges from within government and the NPS. While the IPOA board and staff have done a fairly good job with the successful investigation and prosecution of a number of cases of police violations, they are yet to get the requisite support from the executive and the NPS high command.

The IAU on the other hand is yet to take off, having been denied the requisite financial and infrastructural support to spearhead accountability from within, even though conventional wisdom has it that institutional transformation is best guaranteed in the long term when championed from within, when your internal champions gain traction and support from the senior leadership

As we approach the August 2017 general election, it is critical for all stakeholders to place policing reform at the top of the national agenda as we await a new government in September. This, I believe, will require a national conference on security sector reform to refocus the agenda on what this country gave itself with the promulgation of the Constitution of Kenya 2010: A police service that embraces professionalism and protection of human rights.

[1] Guns: Our Security: Our Dilemma, Independent Medico-Legal Unit, Nairobi, 2014.

[2] The Daily Telegraph: Kenyans five times more likely to be shot dead by police than by criminals, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/kenya/10941227/Kenyans-five-times-more-likely-to-be-shot-dead-by-police-than-by-criminals.html;

[3] The Daily Telegraph June

[4] Violence

[5] The Star, IPOA probes APs over killing of top police boss son in Utawala, http://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2017/04/12/ipoa-probes-aps-over-killing-of-top-police-boss-son-in-utawala_c1542697 , April 12th 2017.