In Memory of The Charleston Nine.

Tomorrow the sun will rise at nine,

And nine thin blades of grass will sprout straight,

Each single blade,

Tall and erect, green heads, sharp edges held straight,

Listening to the crickets at dawn,

Cracking their wings nine times,

Salute!

Tomorrow at nine,

When the sun is warm and the earth is happy,

Standing at the cliffs of Charles-Stone,

With the winds at their command,

Beautiful butterflies,

Ready!

But wait,

What if each bullet had a name?

What if you could call each bullet back?

Soon, when it leaves the barrel,

Silence it,

From cracking the air with the sounds of broken bones,

Of hate,

Of men, silent forever,

And each bullet was put to bed, to sleep,

Would that bring back life?

Nine times?

My father.

I came to this land in September of 2014. Just when Ferguson, Missouri was happening. I watched most of the rioting on television. I was not very disturbed that Michael Brown Jr. had been shot dead. I was stressed that Darren Wilson had fired at Brown twelve times. And hit him six times. I have watched people hunt lions in Africa. And warthogs. And other wild animals. There is hardly enough time to fire twelve times at a charging buffalo. Let alone an unarmed human. I was shocked at the hate and fear that would push a man, a police officer, to execute a fellow unarmed man in this heinous fashion. It all looked like a bad hunting trip. Something out of a horror movie.

I settled in front of the television. The communal loss and mourning flowed from the television, in clear crystal images. Into my veins. I watched it on repeat. Seeking meaning for it all. One of the people visiting my house wondered out loud what was wrong with these people. Why were they burning and looting? And fighting the police? She had made no comment about Brown’s death before this. She was only concerned about the loss of property.

It occurred to me right there and then that I was alone. Like many black people who go to parties with their white friends. And only learn they are alone when the police appear. Or when they get pulled over. And their skin colour suddenly makes them fair game. To be prodded. Inspected. Violated. Knelt on. The people who were bearing the pain of this murder, and the travesty of justice that would follow, were not dining with me at the same table, or dancing with me in the hipster bars that I go to. No. They were the ones out there in the streets. They were the prey. I was learning quickly. That not even a law education from Harvard can save you from the hunters of black bodies in this land.

My father.

I am folding into myself. Like a flower that has sensed a warning in the environment. A change in temperature. The coming of a storm. Of death. I am folding into myself to protect my seed. And the future generation. America has been good to me. Yet I am hesitant to freely enjoy its fullness. There is a tightness in my chest. There is adrenaline rushing through my veins. Too much cortisol is pouring into my system. Every time I hear a police car. To one group, the sound of a police siren is comforting. A sense of guaranteed protection of life and property. For others, it portends death.

Let me tell you a story. One day I was visiting a friend of mine. In front of his house, I met this man who looked like me. He was black. Of medium height. No visible body markings. He fit the description. Like in the emails I get at work. There has been a case of suspected robbery. The suspect is a black male. Of medium height. If you see a person of that description, please call 911. That is me. I fit the description.

This man approached me with measured caution. He called me brother. I came into town today, he said. I came to look for my cousin who cuts hair around the corner. I have learned that he left town. I am asking you for ten dollars to buy dinner. As I figure my way around. I did not feel threatened in anyway. He looked like me. Black man. Of medium height. I shook his hand. I gave him a twenty. And wished him well.

I stepped into my friend’s house. Before us was expensive whisky. And overpriced education. And imagined success. And sports. I told them about the man I had just encountered. The white men were unanimous that I should have called the cops on the guy. Let the police deal with it. They wanted the police to get on with their duty to the society—to remove the bad guys from our neighbourhoods. Men like the one who stole ten minutes from me. They were not welcome to wander around these neighbourhoods. This man I had encountered fit the description. I suddenly feared for him. Wondering where his night would end.

My father.

I am more aware of my surroundings. You are wondering how this feels? How freedom and equality feel in the land of the free? Sit down. Let me tell you. You remember what grandfather would say? That when the hairs on your neck stand stiff, when you step out at night. It is because there is a leopard watching you. Run back inside. Yell for help. Every able-bodied man must then get their spears. Leave the warmth of their wives. To hunt the leopard. Kill it. And its spirits. Before it kills a child. For nothing tastes as good as freedom. There is no gift more precious than freedom that a man can give to his son and daughter. Not here. My father. The freedom is only guaranteed to the offspring of certain peoples. The others can’t breathe. These people have found a way to extend the fear of the slave master, legally, into the heart of the black community. The police are their vehicle of delivery. The justice system reinforces it. In this way, the law has been used to bend the black man into shapes that work for America. Society is happy to spend funds on heavily policing the poor rather than on initiatives aimed at reaching out and integrating the black communities. Communities that have raised heroes in sports and the arts and have contributed to American culture. My father. I hope I do not sound regretful. Or Resentful. Or defeated.

My father.

It is June of 2015. It is almost a year since Ferguson, Missouri. It is almost six months since three Muslim students were massacred in a housing complex near my house, over a parking space dispute. On that day, the darkness in this white man’s heart, engulfed the whole community in a black blanket of sorrow and sadness. It would remind this sleepy community that the leopard is out there. Crouching. Ready to pounce from behind historical lines of racial tensions. And eat the minority. I was quickly learning about the fault lines of this country. The volcano beneath the smiling faces. The coded words. “You speak English so well”. “You should thank God you are here”. “It is very hard to be American, be thankful”. “We thank God for you”. “This place can’t be worse than your home”. I was also learning that it is harder to grow up black in Chicago than it is to grow up in Jericho, Nairobi. That America was created along racial lines. And morality also flowed like an electric current, along the boundaries of these lines. That it is so hard for the church to be one. That a compromise had to be reached, where Jesus was sliced in two, along racial lines. The one in black churches was shouted at. Implored. Yelled at. In spirit. Into action. Jesus save our black men, from death, from the police. From gun violence. The one in white churches, was thanked for the good life. For the good neighbourhood. For one country. Under God. For the gift of police. Blue lives matter.

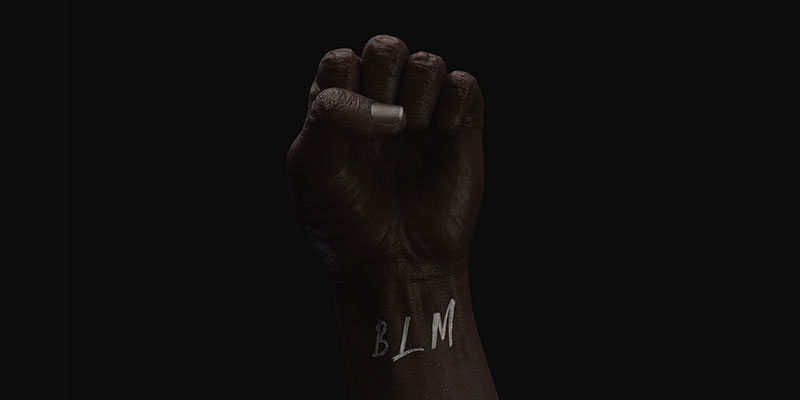

Following the shooting in Charleston, I found myself in a black church, mourning. The preacher was white. I was disappointed because I wanted the rage in the sermon to flow to me through black lips. Black voice. Black anger. The voice that had trembled, while explaining to a police officer, why she was sorry for driving two miles over the speed limit. A voice filled with scorn. Twisted. Yelling. Fuck the system. Broken. By the loss of another brother. The sermon was meek. Organised. I wanted chaos. I wanted to question God. Why. The loss was palpable. I started folding into myself. I cried. I wrote poetry. I had been here hardly a year. And all the safe spaces were crowded with violence.

My father.

There are things we should not tell children. Me, I have started talking to Theo. Explaining to him, that though the police remove the bad guys, like they do in the movies, they also kill a lot of innocent people. Black people. People like me. That is why we have been marching. And that’s why I have not been able to sleep since George Floyd died. And Ahmaud Arbery. I am permanently suspended in this dream where I am riding my bike down a road. And a pick-up truck sneaks up behind me. They yell something. And everything descends into black beautiful petals. I wake up scared. Unable to sleep again. I think I am having nightmares about Ahmaud Arbery. They did not want him jogging in their neighbourhood. So, they chased him down, run him over and shot him in the chest. His running was making them so mad. So hateful. That they chose death, as the rightful punishment for him.

My father.

You know about Floyd. You called me. And talked to me. You don’t know about Breonna Taylor. You didn’t know about Trayvon Martin. You don’t know about this pain. You know about Dr King. You know about Malcolm. You bought his autobiography so that Kevin and I could read it. When we were 14. You don’t know about Emmet Till. How death can come to a black child falsely accused of whistling at a white woman. Who can kill a child for whistling? And walk free. And Philando Castile. And Tamir Rice. And Sandra Bland. And Eric Garner. And Freddie Gray. The list is longer than the length of the Nile. My father. I am folding into myself.