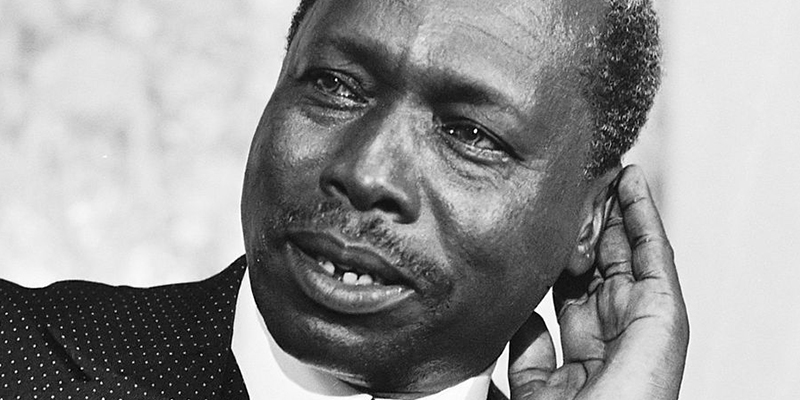

The death of former president Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi has drawn mixed reactions from various quarters. On social media, there are those who are feting his strengths, from his health and discipline in keeping physically fit, to the Maziwa ya Nyayo school feeding programme, to keeping Kenya “an island of peace”. Then there are those who remember him as the man who ruled Kenya with an iron fist, under whose regime there were several hugely controversial and still unresolved murders, most glaringly that of former foreign affairs minister Robert Ouko. Then there are those others who, in cynical Kenyan fashion, are demanding a public holiday because, well, am not sure why, but that’s just the Kenyan condition, in its fearful and wonderful glory. To say the reaction to Moi’s death is a mixed bag is an understatement. That different people have different ideas of his legacy should not be something to be resisted but something to be accepted and celebrated.

I remember as a child in the early 90s sitting with my late dad, an avid historian—and my sisters, watching Moi on television addressing a huge crowd. One of my sisters wondered why people would choose to come out and cheer such an awful politician with such a terrible political record. (For context, I was born and raised in a region that made no bones about its disdain for Moi. Combine that with a household that approached politics with a critical fascination and that conversation wasn’t out of place.) It is my dad’s response that I so clearly remember: “Regardless of what we know or think about him, look at that turn-out, history will judge him as a popular man”.

In a country with a short memory, a terrible grasp of history and a hugely youthful population where more than two-thirds is under 25 years, it may be difficult to recall a time when the level of expression and openness we are currently experiencing was unheard of. That we can say what we think about the late president should be celebrated as a sign of freedom of expression, one that wasn’t available under his regime. Moi is like that elephant in the old poem that several blind men touched and interpreted to be different things. Just like the elephant was a wall, a fan, a tree, etc., Moi was a dictator, a tribalist, a corrupt individual, a political strategist of Machiavellian genius, the man who ruined a country, the tree planter, the gabion builder and, of course, just Baba. Baba who walked with his ivory rungu (with all its phallic symbolism), the emblem of his power and exclusivity. Moi was all these things to different people.

However one felt about Moi, we can collectively agree that Moi made his presence felt everywhere. It was in the way his activities dominated the news bulletins, in the way graduation ceremonies were at the mercy of his diary because he was chancellor of all public universities. It was in the way we were reminded of his benevolence through the milk that was periodically delivered to primary schools. It was in the way development projects were withheld from areas of the country he perceived as opposed to him. It was in the way schools and other public institutions were named after him. It was in the way he hired and fired senior government officials on a whim and kept them glued to the one o’clock news. How he mastered and liberally weaponised divide-and-rule politics, creating and destroying political careers like the all-powerful sovereign he had fashioned himself to be. It was in the various random acts of kindness he extended to certain citizens, for which the recipients were eternally loyal whilst others viewed them as nothing but exercises in pious performativity. It was in the way he named a public holiday after himself and on the very first Moi Day got the popular Congolese musician Mbilia Bel, then in the prime of her career, to re-write one of her hits and perform the song live, in praise of his regime. And it goes without saying that the song was played all the time on national radio. Many other songs were composed in his praise, ad hoc compositions for the numerous Harambees he attended. Moi also captured the national imagination with his almost invisible private life. The wife we only heard about but never saw, not to mention the rumours of the incident that led to her banishment. Moi captured the state, made the ruling party KANU his domain, and remained a fixture in the visuals and imagination of Kenyan citizens. He was The Sun King of his time, l’état, c’est moi could have been his alternative slogan, it certainly was the zeitgeist of the time for those who remember his rule.

It is Moi’s luck that he ruled at a time when the flow of information could be controlled by the government. With limited independent news and TV stations outside of the compromised state broadcaster, it was difficult to get news narratives outside of what the government wanted reported. Distances, in terms of geography, and lack of freedom of speech meant that we got to hear what the government wanted us to hear and any alternative stories were quickly killed, and if they couldn’t be contained, they would be easily delegitimised. Of course, it really helped that his regime existed in a technologically different time, before the era of citizen journalism. He did not have to deal with the narrowcasting headache of citizens practising everyday resistance by filming, shaming and naming his political misdeeds, socially organising beyond geographical limits and demanding political accountability.

And so there are stories that we will never know unless we actively endeavour to record them as part of our history. We will never know the accounts of the victims of tribal clashes in Kenya, particularly the 1992 clashes. The Parliamentary Select Committee chaired by Kennedy Kiliku compiled a report, popularly known as the Kiliku Report, but it was shot down by Members of Parliament and its findings aren’t available to the public. One of the few things we do know is that six cabinet ministers were adversely mentioned in the report and they wasted no time in pre-emptively lawyering up. This is but one example of the histories that we have failed to record under the Moi regime.

Reminders of Moi’s violence are present with us, physically and metaphorically. They are in the Nyayo House Torture Chambers where unspeakable acts of violence were committed against people whose only crime was to have a contrary imagination of societal happiness. They are in the shame of our complicit national silence, that we refuse to honour these individuals who risked so much to give us the political freedoms we enjoy today. The freedom that allows me to write this article, which at the time of my birth would have been labelled seditious material, eliciting dire consequences. It is in the failure to open the torture chambers to the public as a memorial to our dark history. We are reminded of him by the Nyayo Monument at Uhuru Park which looms over the city like an avenger ready to whip errant citizens back into line.

Perhaps Moi’s greatest political legacy is being felt today as his political acolytes of the early years of his rule now run the country. In a country that is struggling economically and experiencing a social breakdown of order of sorts, many have been quick to draw the symmetry between the current times and the economic dire straits of the Moi regime, especially from the 90s to the early 2000s. The Jubilee government has been kind to Moi, sanitised him some will say, and helped erase his little black book of political misdemeanours, leaving in its place the image of a benign granddaddy/Baba whose leadership Kenyans fondly miss and yearn for. More glaringly for those pursuing the symmetry angle, is the transition politics Kenya is currently undergoing. Deputy President William Ruto is facing hostility and frustration from sections of a government that he is part of, and this has been linked to efforts to prevent him from ascending to power in 2022 when President Uhuru’s term comes to an end. Ruto—who entered into a political pact with Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 as a way of countering the charges brought against both of them at the International Criminal Court in The Hague—has been likened to Moi, who faced humiliation and opposition from a section of President Jomo Kenyatta’s regime.

As Kenyans get to express their various opinions about their second president, he will also be remembered abroad. For the people of South Sudan, there will be those that will remember the support Moi gave to the Sudan Mediation Process in one of Africa’s longest-running conflicts, a process that, under the stewardship of Rtd General Lazarus Sumbeiywo, led to the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 and ultimately to the birth of South Sudan as a nation state in 2011. During the Sudan civil war, the Kenya government gave the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) leadership tacit support, allowing them and their families to live in Kenya and taking in refugees from South Sudan. Kenya’s role during the cold war cannot go without mention either. As a littoral state, geographically positioned in the horn of Africa, Kenya was of great interest to the Cold War powers. The country allied itself with the western capitalist bloc and proved to be a significant American ally, signing military agreements giving the US naval access at the coast. At a time when most countries in the Horn were deemed to be socialist-leaning, Kenya became a key entry point for the capitalist bloc in the proxy Cold War excursions in the Horn of Africa.

A lot can be written about Moi; these contested narratives about him should be taken as a boon, an opportunity to write the complete and contrary histories of this man who ran a country for 24 years as head of state but whose political career preceded the birth of Kenya as a nation state. This was a man who joined the Legislative Council in 1955, was part of the Lancaster House delegation of Kenyan leaders that negotiated our country’s independence. Moi was in the first opposition government of newly independent Kenya as a member of Kenya African Democratic Union, KADU. He served as a cabinet minister and eventually as vice-president under Jomo Kenyatta. All this took place more than two decades before he ascended to the presidency. All Kenyans, and specifically the critical thinkers of our time, ought to explore the structural consequences of Moi’s regime on the Kenyan condition. While Moi might have been credited with keeping Kenya peaceful during his tenure, as events in 2007/2008 would show, this was but a Potemkin village whose internal contradictions eventually unravelled. The vagaries of Moi’s regime, the physical, economic, political and psychological violence all took a toll on the nation state; something had to give. He perpetuated a political legacy that he had inherited, where the country was at the mercy of powerful political and economic interests keen on extracting and enriching themselves. Beyond the political repression were the economic consequences of his regime: rampant looting and corruption. It is our responsibility to critique these political and economic actions and their effect on the social breakdown of our society.

That we must deconstruct and interrogate Moi’s political career is not just about freedom of expression. It is our civic duty. It is our responsibility to future generations whose only glimpse into who this man was will be in the written and oral histories we will leave behind. We should as a nation engage with this man’s political career especially since he was present during so many critical political moments in Kenya’s history. Part of understanding our history involves understanding pivotal political personalities around this history. So we must critique him, we must hold him accountable for his wrongs, we must allow the stories he suppressed to be told. This is necessary as it is also cathartic. This exercise can be the beginning of an exorcism that this country’s troubled soul so desperately needs. From Moi’s death we can find life, we can choose to reconstruct what our country will look like into the future as we discard the ills his regime and those before him foisted on us. From these contested narratives we can set a new trend where we honour dead public figures by thoroughly examining what their life as public leaders was. This is how we create a culture of transparency and accountability, holding our public leaders accountable in life and even in death, particularly those whom we couldn’t fully hold to account during their lifetime. Ours is a nation with a troubled soul and this could be the beginning of our healing.

Moi’s death will certainly expose Kenyans to an experience similar to what Zimbabweans went through following the death of their founding father, Robert Mugabe, in 2019. There are those that will love him and will let that love come shining through. There are those that will hold him accountable for the grievous political, economic and social injury he inflicted on the country and its citizens. For those whom he wronged, the victims that never received recognition, compensation and/or closure, they will experience a myriad of emotions; from anger at justice miscarried, to sadness. It is a time they are likely to relive their trauma at the hands of the former president. The Kenya government position is clear: instructions for flags to be flown at half-mast, national mourning up until the burial, and a state funeral. A hero’s send-off. Given that the President and Deputy President have a shared history with the late former president, this doesn’t come as a surprise. For the rest of Kenyans, we are passionately split into two constituencies: those that remember him as vile and reprehensible and those that remember him as Baba. Then there is that other constituency that couldn’t care less, the one that just wants a public holiday.