The little girl, knees buckling, made it to the grass verge and set down her twenty-litre jerrycan. The year is 2016. Nothing says “Third World” louder than a yellow plastic 20-litre jerrycan. The jerrycan has become a symbol of underdevelopment. The girl tells me where she got the water and where she is taking it. It is a trip of a good 400 metres or more, well outside the 200-metre benchmark development indicator set by the City Council. The indicator does not factor in the weight of the water or the age or weight of the carrier. Or even the roughness of the surface over which it has to be carried.

I am too ashamed to ask the girl whether she collected the water from a spring or a protected spring – a spring that is cemented over with the water gushing endlessly through a pipe or from a stand-pipe, for which the owner would have charged Ushs 200 per 20-litre jerrycan. I made that mistake once with a child I met near the Mwanza ferry. I asked him why he did not scoop water out of the lake near where we were standing, rather than going the extra 50 metres to the unprotected spring that naughty older boys used to stir up with a stick after collecting their own supplies, leaving a swirling clay solution that would be unsafe to drink for a couple of hours. The child had looked at me and listened patiently to my reasoning before saying two words: “Embwa nno?” [The dogs?]

There are wild dogs on the shore.

I fought the urge to give him something for pancakes; I did not want him to get used to taking money from strangers.

In my own childhood, there was a time we wanted to go to the well to hear the ghosts calling. My cousins and I spent a good part of the morning trying without success to create a water shortage by stuffing coffee beans up the standpipe. My experience with carrying water in earnest started when water shortages were new and seemed temporary. Our secondary school was half-way up a hill and water was pumped from a spring into our tanks. After several attempts, the school managed to catch the gang that was slowly digging up the pump and generator. The gang members were caned in the office before they revealed who had sent them (he was said to be a government minister) and Sister Moira announced she did not want the responsibility of guarding the equipment. It was put in her office for safe-keeping.

The flush toilets were locked and the keys put in an old Cadbury’s chocolate tin and taken to the staff room after which we resorted to “Pittsburgh” – the square beyond the hockey pitch behind the dorms that was lined on three sides with pit latrines. The sisters, with their relentless attention to detail, had planted a shrub that emitted a pungent perfume in the evenings and on which we used to spread our cardigans before we went in.

The building of pit latrines has since become a growth industry, with many NGOs, both foreign and indigenous, marketing their own improved designs. Every now and then someone forlornly comments on the fact that there were toilets in the region before the explorers arrived. There were laws protecting the hygiene of water sources: it is still anathema to bathe at a spring. The type of receptacle one is able to use is governed by whether the source is a spring (a wide-mouthed receptacle for catching) or a pool (a long-necked gourd for scooping), all directed at preventing contamination. And now we have NGOs sticking posters in public places telling us that we need to wash our hands.

The pictures in the development supplements of newspapers show tin roofs with spinning flues to extract the odour of ammonia. Appropriate technology. With such modest ambitions, it is no wonder that “local” has become a pejorative word. Not local as in barkcloth, listed by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity treasure or our intricately-patterned handmade palm-frond mats that you can see in drawings by the Desert Fathers from 300 AD, or traditional Mayan loom-woven ponchos, or even Waterford crystal. Local as in inadequate, inconvenient, laborious, non-progressive and usually plain embarrassing.

For bath water, we had to go through the main gate (an expellable offence without permission), up to the top of the hill where the old mission church is, and then down the other side to the spring. Easily 200 metres. The descent to the spring began and we were surprised Sister Moirathe Headmistress got as far as she did, well over 5 metres of wet slippery earth, almost vertical in places. We girls slithered down the rest of the way, removing our rubber slippers, now hindrances heavily caked with mud, and laced them around our wrists, before scooping up bucketfuls of water. That was the easy part. On the way up, we kept sliding back, tipping out precious water and making the path still less passable. Back at school we only had enough left to wash ourselves and to scrub our slippers. Our soiled clothes had to wait until Sister found another solution.

We began to queue at a standpipe (the only one still issuing water) in the once out-of-bounds teachers’ compound at the lowest point on the hill. We learned to use only half a bucket of water for our evening (we still called them) “showers”, and save the rest for the morning. The closest I came to a physical fight at school was on the morning I found my bucket at the foot of my friend’s bed, empty.

Ten-litre buckets were rapidly replaced by 20-litre jerrycans that we carried in short, rapid, tripping steps, a metre or two at a time. Once industrial by-products discarded by vegetable oil processors, jerrycans are now manufactured especially for water. They are a fixture on school requirement lists, together with a slasher to cut the grass with, a knife to peel the plantain and cassava before dawn and a scrubbing brush for the classrooms, dorms and verandas. The support staff resigned en masse when Sister could not raise their wages. Water became a privilege as did leisure time.

“It is not my Economic War.” Sister reminded us whenever we murmured.

The situation never returned to the pre-Economic War standards of the early 70s. After I finished school, a little cousin was brought to see us – it was before petrol shortages killed the tradition of dropping in to greet people. The child vanished briefly before being found in the bathroom, all taps running.

“She does that whenever we go visiting,” her mother explained. “The water supply has not been restored since she was born.”

Eva was three-years-old.

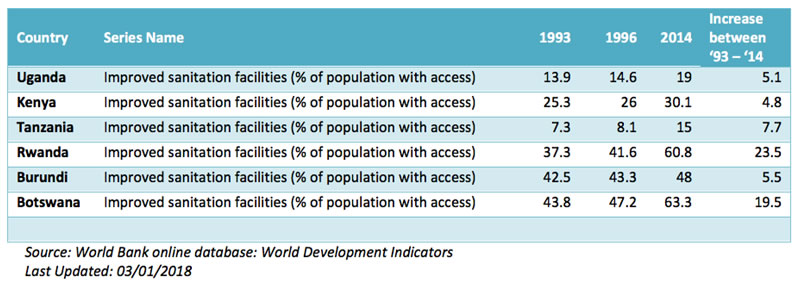

That was the 1970s. Since then Uganda has been “liberated” more than once and Africa is said to be rising. Yet access to water remains problematic. According to the latest World Development Indicators, only 19% of Ugandans have access to improved sanitation facilities[i]. This compares poorly with Kenya’s 30%, Rwanda’s 60.8%, Burundi’s 48% and Botswana’s 63%.

Furthermore, between 1993 and 2014, during our post-war boom, Uganda only increased that access by 5 percentage points while Rwanda roared ahead with a 23% increase. Uganda’s allegedly stellar economic growth of the period seems not to have translated into a lived experience for the majority of her citizens.

A clue to the puzzle can be found in The Economic Development of Uganda (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1961), a report published after the World Bank was invited by the imperial government to prepare a post-independence development plan. It is a 350-page tome that reads as though it was written in 2016 – the issues are still the same: the need for power, piped water, irrigation, more roads and mechanised farming.

However, World Bank officials were impressed by the method and level of investment in social services. They noted that 60% of the cost of capital development was met by Ugandans in bulungi bwa nsi schemes. Community members supplied either labour, materials or the cash equivalent. The balance came from the native poll tax, cotton taxes and commodity export taxes levied by the colonial government on farmers (farmers enjoyed real incomes then). Uganda had been balancing her budget for decades using her own resources. Education and health services delivered at the Ssaza level were funded by missionaries, indigenous community taxes (the Kingdoms and other communities were allowed to levy taxes for this purpose) and school fees. After 1921, when the colonial government took over the schools[ii], they began to supplement these resources with grants from the same public resources mentioned above. The colonial government, according to the Bank’s review, contributed only machinery for road-building and materials not available locally. It was a method introduced by the missionaries in church and school projects.

Surprisingly, World Bank officials concluded that this arrangement needed restructuring, that too much was being spent on social services.

“First, there is the need for restraint with respect to expenditures. The public since World War II has grown used to steady expansion of services provided by the Government [Note: funded by taxes and levies on the people [iii]]. Public expenditures have indeed risen at a very rapid pace [….] Nevertheless the existing situation requires a dampening of the past trend. Fiscal policy should aim at maintaining recurrent expenditures for regular services at about the level they reached in 1960/61. Increases in these should be restricted to inevitable items such as loan charges on foreign debt incurred […] and recurrent impact of necessary capital investment.” (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 1961, p. 49)

The logical conclusion to be drawn is that in order for Uganda to be able to afford the new loans, it was being prepared to take out, and to continue to pay pre-independence loans, expenditure on developing the basic infrastructure and providing social services had to be cut back. The loans themselves benefit foreign suppliers, project managers, engineers and, in the case of Chinese loans, foreign labourers imported to do the work.

Since then loans have been taken out, restructured and extended and become unmanageable while the development of infrastructure and the provision of basic services, including water, have stagnated.

[i] Improved sanitation facilities are defined by the World Health Organisation as those connected to a public sewer and a septic system with ventilated pour-flush latrines or simple pit latrines.

[ii] Colonial accounts do not reflect the massive input of funds, skills, labour and materials of the churches to the economy per Tourigny Yves, So Abundant a Harvest (1979)

[iii] The bulk of the profits from cotton exports (between 60 and 70%) went to the UK treasury. See Mukherjee R., Uganda: An Historical Accident?, Class, Nation, State Formation, pub.d Africa World Press, 1985. Furthermore, during the World Wars, Uganda cancelled its entire development budget of GBP100,000 and contributed the funds to the war effort (source: Annual Accounts of the Protectorate of Uganda 1939.)