You never step into the same water in a river twice. Not one minute later, not years nor decades later. So, while this moment where we are again called upon to protest a particularly heinous spate of femicides in Kenya is familiar, it is not the same. We are here again but we are not the same, the country isn’t the same, the world isn’t the same.

I find I must keep reminding myself of this after more than three decades of working on what is referred to as Gender-Based Violence (GBV) or Violence Against women (VAW), but what I choose to refer to as Violence Against Women By Men (VAWBM). In referring to it as VAWBM, I am borrowing from Dr Pumla Dineo Gqola who, in her book Rape: A South African Nightmare states, “We run the danger of speaking about rape as a perpetrator-less crime.” By using labels such as GBV or VAW, we run the risk of speaking about violence against women as if it merely is, it just happens, as if it has no perpetrator, and as if the perpetrators are not almost always male. VAW becomes a perpetrator-less crime, and without a perpetrator, all our attention and solution-seeking is mistakenly focused on the women victims and survivors.

As an undergraduate student at Northeastern University, I volunteered at the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center (BARCC). Later, I worked with the State of Massachusetts at the Child at Risk Hotline and then at Help for Abused Women and Children (HAWC) when I lived in Salem, Massachusetts. As a Corporate Associate, I represented, pro bono, women survivors of domestic violence as well as political asylum seekers survivors of sexual violence.

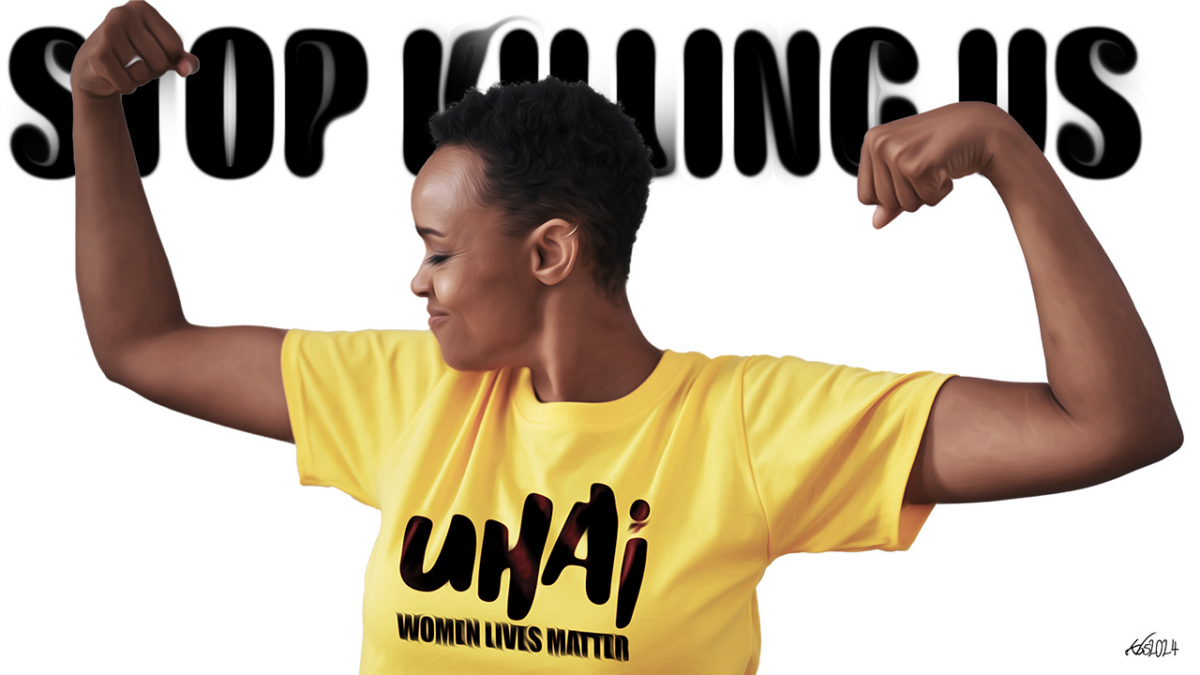

A few years after moving back to Kenya in 2005, Gathoni Kimondo and I co-founded Kimbilio Trust and started the first volunteer-staffed hotline for women survivors of rape and intimate partner violence (IPV). I then went on to work on the policy side as an advisor on gender to the Cabinet Secretary responsible for Gender. On the advocacy front, I have been privileged to work alongside a committed and growing African feminist community, organising and participating in historic protests – the #TotalShutDown and #StopKillingWomen marches in Kampala in 2018 and in Nairobi in 2019. #TheTotalShutDown protests are the brainchild of our sisters and Gender Non-Conforming persons in South Africa, and the banner under which they have organised some of their more recent protest actions against femicide.

As part of the #TotalShutDown movement, African feminists from around the globe have generated awareness and advocated publicly on the platform formerly known as Twitter for heighted action and more urgent coordinated response from government actors and agencies in South Africa, Uganda and Kenya.

In between these engagements, there was the episodic organising around particular cases of VAWBM – more cases than I can remember. But some are seared in my memory; for instance, when Governor Evans Kidero was recorded by a local new station slapping the Nairobi County Woman Representative Rachel Shebesh at City Hall in 2013. This case is significant because it points to how a culture of misogyny and one that permits and even encourages VAWBM and femicide (the ultimate expression of VAWBM) is sustained. Despite significant protests and demands by women and women’s rights organisations for Governor Kidero to be arrested, charged and removed from office, he faced no consequences for his publicly recorded display of violence. Indeed, he went on to complete his term.

Governor Kidero was never sanctioned by any state agency, and nor did he face disciplinary action from his political party. Since then, he has run for political office in 2017 and 2023, and was appointed by President William Ruto to the position of Cabinet Assistant Secretary in 2023. This case is important because, despite being recorded slapping an elected woman member of parliament, Governor Kidero suffered no legal, social or political consequences for his actions. Instead, the message sent out was that such actions were acceptable.

In 2018, Sharon Otieno, a pregnant university student who was in an intimate relationship with the Governor of Migori County Okoth Obado, was murdered. Governor Obado and Governor Kidero were political colleagues, both serving as governors during the 2013–2017 term. Neither governor was impeached. This is especially significant when we consider that Governor Kawira Mwangaza of Meru has been impeached twice in less than a year – and not for violence. As a result of relentless advocacy and pressure from women’s rights organisations, Governor Obado was arrested in 2020, but it was five years before he and others were arraigned in court. As of this writing, judgment has yet to be rendered in the criminal case against Governor Obado and others accused of Sharon Otieno’s murder.

In The Feminist Fear Factory, Dr Gqola reminds us that “Patriarchy relies heavily on the symbolic; on the arrangement of certain events as though they are not constructed, as though their internal logic is natural, automatic, and inevitable.” We cannot overstate the symbolic impact of these cases. When men – particularly men in power – commit acts of violence against women with impunity, it normalises VAWBM for all men and serves as important social signalling of acceptable and/or permissible behaviour.

I invoke my history of doing this work and of these particular cases to remind myself how far we have come, how much we have done, how much remains to be done and to justify my impatience – our impatience. Also, to demonstrate not just my expertise, but our global expertise as African feminists theorising, advocating and organising on VAWBM and especially on femicide. In The Feminist Killjoy Handbook, Sara Ahmed states that “Activism generates knowledge”. African feminist activism on femicide has created and continues to create a wealth of knowledge that is fuelling an unprecedented political activism centred on women’s non-negotiable belonging, as well as our right to security, safety and dignity.

Finally, I reiterate these facts for the record. African feminist activism and knowledge are often overlooked, unremarked upon, co-opted, deliberately forgotten or violently erased. In the same way that the 2020 Chilean protest performance/song El violador eres tú – The Rapist is You – was a powerful global contribution from Chilean feminists’ protests challenging the state and societal approach to rape, pointing to both individuals and institutions as rapists, the #TotalShutDown marches and movement – a transnational African feminist movement – is an important contribution to the organising against femicide on the continent and globally.

So, while recognising the familiarity of femicide and of this moment, I refuse to give in or give up. To quote Sara Ahmed again, “We have to keep saying it because they keep doing it.” We must not tire at the repetition and the reciting of facts, the repetition of demands. Our activism is fuelled by this “killjoy truth” and by the feminist record that reminds us that we have made and continue to make change. From changes in the framing of the issues, to educating our communities and leaders about the systemic nature of VAWBM and IPV and, most importantly, rejecting the individual responsibility for the violence committed against them that is frequently laid at women’s feet.

“We have to keep saying it because they keep doing it.”

Most importantly, we will continue to speak because as feminists we refuse to accept the false belief that VAWBM and femicide are inevitable, immutable aspects of our societies and countries. We aren’t, therefore, merely protesting individual acts; we are challenging state-sanctioned and sustained systems that are, in their inability and/or refusal to hold men criminally or in any other way accountable for violence against women, creating a culture of criminality where women’s bodies and lives are disposable. We do this despite the fear this violence releases like a virulent virus into our societies.

In recognising the familiarity of this moment, the familiarity of femicide and our past protests and actions against it, we are also doing important feminist political work. In The Female Fear Factory, Dr Gqola states, “The recital of women’s continuous defiance, feminist resistance and multigenerational claims to freedom matter as much more than mere examples.” They also serve as an “ … interruption of the Female Fear Factory”. Dr Gqola also reminds us that “We must never leave patriarchy uncommented on as we illustrate its workings.” In Living a Feminist Life, Sara Ahmed states: “A feminist movement depends on our ability to keep insisting on something: the ongoing existence of the very things we wish to bring to an end.” So, we will keep noticing, interrupting, protesting, challenging until we end femicide. African feminist movement work remains unrelenting because our survival depends on it.

Being a woman should not be a death sentence. As Kenyan women, including LGBTQ+ women and girls in all our diversity, we are tired of the dehumanisation that permeates our existence, the tragically normalised occurrences of femicide, and the pervasive victim-blaming rhetoric surrounding violence against women.