It is “Maandamano Monday” and the smell of teargas and tension lingers in Dandora, a slum settlement on the outskirts of Nairobi. As policemen pre-emptively “contain” protesting residents on the day of planned anti-government protests, there is a general feeling of helpless frustration. Here in Dandora and perhaps in several similar settlements in Kenya targeted by the Kenya police, the simmering disillusionment of the working poor—who are often singled out for state violence—with the government is boiling over into sustained civil unrest. Reeling from the effects of a global pandemic, a sluggish global economy, and the high cost of living, the mwananchi is rebelling against negligent governance and anti-public interest policies in an economic downturn.

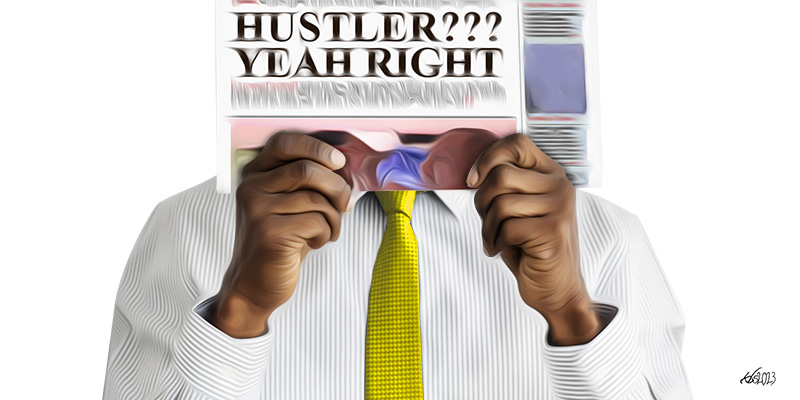

The hopeful fever during the 2022 general election of having a “hustler”—a government outsider, a hardworking Kenyan from a humble background, and a champion of the people—take up the presidential mantle has been drenched in the ice-cold reality of a public debt projected to gobble up more than half of all future state revenue, the lived experience of corruption, unemployment, an out-of-control dollar and the increasingly tax-predatory patterns of behaviour exhibited by President William Ruto’s government that mirror those of the previous administration.

The outcomes of the hustler government are very different from the great expectations the working class had of Ruto; those who bought into the hustler narrative are carrying around their palpable discontent in the same empty purses depleted by the cost-of-living crisis. Specifically, the 2022 campaign period was inundated with the “hustler” vs “dynasties” narrative that painted Ruto as the valiant underdog and champion of the public interest fighting the “system/deep-state/power-elite” represented by Raila Odinga and his bloated benefactor, former president Uhuru Kenyatta; the narrative of David against the Goliath that is the machinery of the state was embedded in Kenya’s collective psyche. It is this very narrative that is now working against Ruto—another unmasked Goliath. The 2022 elections revealed that the social contract between an elected government and its electorate is changing in Kenya. Rather than blindly following tribal or kinship ties, the people, vested with democratic power, are increasingly interested and responsive to the services on offer by the body politic. In addition, political competence is fast becoming inextricable from the ability to understand, craft, and implement beneficial economic policies that visibly serve the public interest. A task it seems the Ruto administration is not up for.

A quick post-election survey of the policies, directives, and appointments that have characterized Ruto’s presidency makes evident that it is business as usual for the Government of Kenya (GOK). Business as usual (BAU) is characterized by political but unnecessary appointments that further add to the bloated wage bill, policies that are anti-public interest and pro-special interests, and government human resource policies that award unreasonable and immoral perks and concessions to those in the highest echelons of power at the expense of a progressively insolvent taxpayer. BAU is a pattern of behaviour that must be considered in context, to better understand why Ruto’s administration will suffer from the same poor governance path dependence.

History and incentive design

The coercive intent of the British colonial administration in Kenya and beyond framed executive will as “the law”. This was to ensure that those who were in power (the colonialist and later their collaborators) could employ “legal means” to maintain power and control for a profitable status quo. Despite the devolution of power through the constitution promulgated in 2010, the original incentive design of the Kenyan government remains pervasive.

In the Western adaptation of democracy, policies, regulations, and processes are often subject to commonly held constitutional or precedent public interest criteria. This public interest criteria are universally understood and come with a host of checks and balances to review and evaluate policies, directives, and regulations against said criteria. By contrast, here in Kenya, and through no happenstance, the public interest is whatever the incumbent government wants it to be. Masked under feel-good word salads that often include “development”, “growth”, and “vision”, the ephemeral nature of what is the public interest in this country means that every political outfit has its own version of it. To illustrate this loose interpretation of the public interest, the Ruto administration has appointed 50 Chief Administration Secretaries—CASs with no constitutional basis and no parliamentary oversight—for the public interest.

The ephemeral nature of what is the public interest in this country means that every political outfit has its own version of it.

In intent and effect, the colonial administration was designed not to benefit the people of Kenya but to serve foreign interests, rewarding the chosen few collaborators with wealth and condemning the rest of the population to whatever those in power decreed necessary for the the maintenance of a profitable status quo. The prevailing special interests against the public interest (politicians, big business, foreign interests) is the foundational design element of the post-colonial government in Kenya. To understand why Ruto’s administration (like most of the governments before it) manifests the same outcomes as its colonial forefather, we must understand that it is a function of intentional design. Clearly, the reality of Ruto’s administration and most others that preceded it is that, as a decision-making entity, the Government of Kenya has been pursuing special interests for such a long time that it is unwilling or unable to deliver the public interest.

The GOK organizational model

Fully aware that the enduring design purpose of the Kenyan government is to serve special interests, it is not difficult to imagine the skills and characteristics that are required to distinguish yourself and rise through the Kenyan political ranks or the civil service.

Those civil servants who knowingly or unknowingly serve the foundational intent of the first colonial government are incentivized and rewarded by a self-correcting system and organizational culture (pro-active corruption, apathy, and a relentless pursuit of special interests) whose noxious effects conspire to ensure that a critical majority of politicians and civil servants who reach the decision-making ranks of government are morally ambiguous, passive to the public interest, and motivated by the pursuit of personal gain. The countable notable champions of the public interest may be blips in the otherwise calcified system.

These personal characteristics and organizational culture, I argue, transcend political parties and formations. The abrupt and conspicuous cessation of anti-government protests following a “handshake” for dialogue is indicative that even the leaders who are orchestrating civil unrest are not front and centre trying to resolve the cost-of-living crisis and the rising inflation (public interest). They are in pursuit of their own interest; seeking a share in the spoils of the current government and pursuing electoral reforms that safeguard future electoral attempts. Even those champions of the people across the political aisle are holding the incumbent government hostage with the threat of disruptive violence for their own interests (moral ambiguity r the loss of life and property during demonstrations thrown in for free). It is a viscerally clear indication that every veteran politician, civil servant, or political faction has been born, bred, and is well matured in the toxic culture of poor governance, and will, given a chance, manifest the same poor governance outcomes.

They are in pursuit of their own interest; seeking a share in the spoils of the current government and pursuing electoral reforms that safeguard future electoral attempts.

A decidedly anti-public interest culture of governance that took root decades before independence is still dictating governance outcomes in this country. Characterized by prevailing special interests, no significant checks and balances over executive discretion, and a political class and civil service with the Pavlovian conditioning to pursue personal gain, there is nothing in my view, short of a miracle that will spontaneously change this path-dependency. The intentional status quo we find ourselves in must be dislodged by an equally intentional re-design of the intent and systems of governance in this county. In a kind of sad irony, however, the Kenyan electorate keeps hoping to elect a candidate who can change the status quo but instead, is faced with a choice between the exemplary products of a toxic political culture, expecting them to dismantle the very systems they have excelled in.

To manifest the public interest and to curb the prevalence of special interest in government policy, process, and practices, requires a self-awareness and political will to change that seems to be beyond the imagination of this current crop of politicians. Until the intent, practice, and enforcement of government policy align with the public interest, we can expect more of the same garbage can politicians, policies, and outcomes.