In early 2020, just before the pandemic became the word and the life, young Ugandan women took to Twitter to expose men they alleged had sexually harassed and, in some cases sexually assaulted them. These Twitter threads sent ripples beyond the online world, breaking through the national silence about the pervasive sexual abuse in the country.

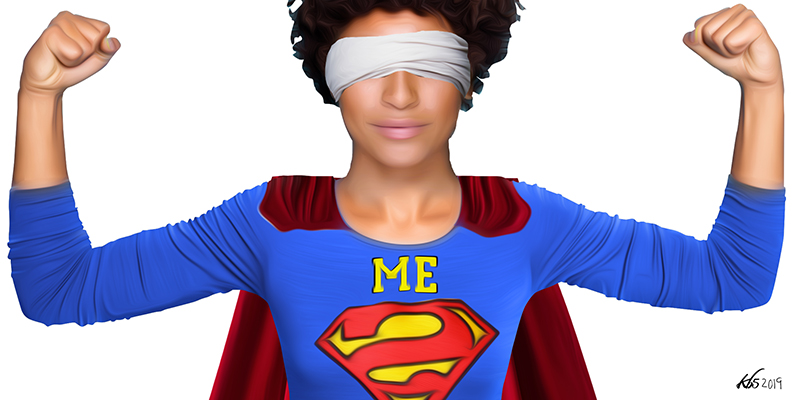

For the first time, young women were speaking out in unison, although for some only momentarily. They shared their lived experiences as survivors of sexual violence, and there was no doubt that many who they outed as rapists had targeted several young women. This was Uganda’s own #MeToo moment, although the push for accountability has been a long and difficult struggle. These young women were building on the bravery of women who had earlier told their stories despite the public wrath they faced.

Sheena Bageine took on the mantle for those who still couldn’t speak publicly about their experience. She received their stories and posted them anonymously. Sheena was arrested, spent a night in a police cell, and was later charged with offensive communication and cyberstalking. This is how patriarchal power operates, from online silencing to state systems ready to “teach a lesson” to women who refuse to shut up.

Young Ugandan women responded, from lawyers to mental health specialists to social media warriors, and the #FreeSheena hashtag trended. Within a few hours, she had become a liability for compromised police who released her on bail. Sheena’s case is still ongoing. But the actions of her peers and the solidarity she evoked shows how agile young women’s mobilization in the digital age is, despite the entrenched hegemonies that still prevail in daily life.

This courage has been inspired by the boldness of a long line of women organizers and resisters. In recent years, Dr Stella Nyanzi, a poet and academic, has set the tone for how radical young women can be if they want to. She has tapped into old forms of refusing to accord civility when dealing with those abusing power. In a poem on Facebook, she defiantly described the president of Uganda as a pair of buttocks for failing to provide sanitary pads to adolescent girls who drop out of school. She was arrested, tried and imprisoned for more than a year.

Millions of young women across the African continent have found a common voice for community building, organizing, and mobilization, taking advantage of the steady increase of internet penetration and the proliferation of cheaper smartphones.

Despite being fewer than their male counterparts online, you can’t miss young African women’s bold outrage and organising. Access to information has always been key to any consciousness awakening. For this generation, despite economic and digital disparities that still remain, information access is much quicker than for their own parents.

By seeing other young women dare cross the lines defining the civility expected of women, they too find their courage to join in small but growing communities. Online spaces have thus enabled pan-African organizing. A protest in Namibia or Sudan can quickly become known in other countries within a matter of hours or days, where others can find ways of showing solidarity.

According to a 2019 Afrobarometer report, the proportion of women who regularly use the Internet had more than doubled over the past five years in 34 African countries, from 11% to 26%. But the report also showed a continuing gender gap of 8% to 11%. Women are less likely than men to “own a mobile phone, use it every day, have a mobile phone with access to the Internet, own a computer, access the Internet regularly, and to get their news from the Internet or social media.”

Women on these platforms face enormous challenges. They are often not considered as expert sources, including by their colleagues within progressive movement campaigns and even when the issues are about lived experiences of women. Or the voices of young women are pigeonholed and only allowed to be audible on “women’s issues.” The marginalization within public discourse extends into the online world, where hierarchies of who is heard are recreated and extended from offline. Many retreat from public platforms into smaller groups of trusted friends. This denies a public voice. And, like men, they must also navigate the growing trend of internet shutdowns and surveillance by governments.

Despite these obstacles, African feminist voices are making an impact both on and offline. As with men, those with greatest access to the internet are disproportionately well-educated and affluent enough to pay the costs of internet access. But the growing number of feminist collectives, with commitment to collaboration and inclusiveness, is a witness to the potential for inclusive politics.

In some cases, issues that have been historically treated as simply “women’s issues” are slowly making it to the center of political contestation. Younger people on the continent are pushing for changes which even their elders, including those who reject the status quo, aren’t providing. Feminist voices are gaining prominence as a crucial part of this resistance.

For example, the Feminist Coalition in Nigeria mobilized to respond to the needs of protesters in the #EndSARS protests that rocked Nigeria in response to police brutality in October 2020. Around the same time in Namibia, youth-led #ShutitAllDown protesters demanded action to address femicide, rape, and sexual abuse.

Formed in 2019 during the popular uprising against the Omar al Bashir regime, the #SudanWomenProtest initiative brought together thousands of women to protest against “militarization, pervasive injustice against women and girls, gendered killings, and the normalization of sexual violence as the result of severe discriminatory laws that are still in effect in Sudan.” Sudanese women had been resisting for decades, but their visibility in the 2019 revolution that overthrew Bashir came as a “shock” to the world, as a video of a woman on top of a car leading protest chants went viral. In March 2021, the initiative continued the pressure on Sudan’s transitional government to remove all sexist and discriminatory policy.

Keenly aware of global internet campaigns such as #BlackLivesMatter, #SayHerName, and #IBelieveHer, young women around the continent have taken their own initiatives. And like their counterparts elsewhere, they have infused intersectional feminist perspectives in their organising. In South Africa they have formed movements for gender justice, such as the #AmINext protests in response to the 2019 rape and murder of university student Uyinene Mrwetyana. But young women have also been key leaders in the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall movements.

Offline, however, young feminist movements and collectives remain marginalized even in young people’s movements pushing for political changes. Young people in Africa are increasingly organizing in search of radical change in the way African nations are governed, to deliver dignity and respect for citizens’ voices. Without the equal participation and leadership of young feminists, however, such a social transformation will remain elusive.

Young African women are learning and teaching that struggles must be linked rather than posed by mutually exclusive alternatives. In Nigeria, for example, young activists in the middle of the #EndSars anti-police-brutality campaign also insist that #NigerianQueerLivesMatter.

Asking young women and queer Africans to put their own struggles aside, in deference to the argument that “national” liberation must come first, as our foremothers did again and again, is not acceptable.

Women were central to the movements for independence and everyday resistance to colonial rule. But often the movements themselves morphed into ruling political class hegemonies. And while we have increased the number of women in parliaments in Africa to match the global average of 25%, actual power in both government and society falls far short of even that achievement. True liberation for women and minorities from shackles introduced by colonial subversion of gender remains elusive. From homes to bars to streets and workplaces, for all the strides made in “empowering women,” we are yet to truly see the liberation of women, in the sense that they can walk this world free in their own skin and their own bodies – free from violence.

And often there’s an expectation from oppressed people, in this case, African young women and gender-diverse people to be civil in demanding for their full humanity to be recognized, with condescending phrases such as “you are asking for too much.”

But who defines what is too much for anyone’s freedom and existence? For Sheena Bageine and Stella Nyanzi here in Uganda, and young women and queer Africans resisting dehumanization around the continent, then the response is to be “too much.” It is only by being “too much” that new cracks in the wall of patriarchal dictatorships can emerge.

–

This article was originally published by the US-Africa Bridge Building Project under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.