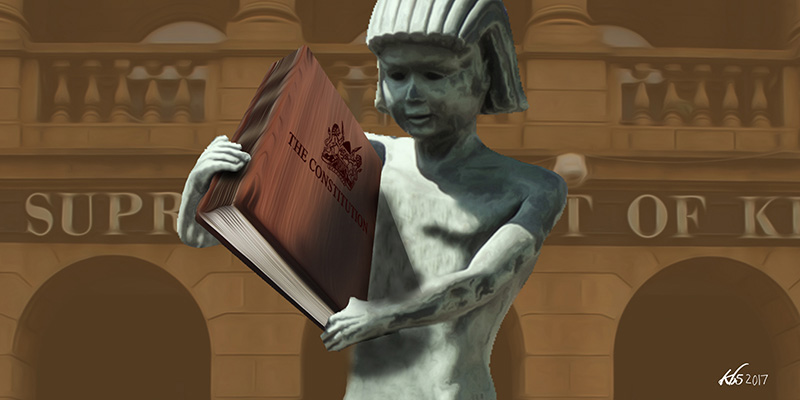

My governor friend and I were discussing the implementation of the 2010 Constitution. He used a metaphor to speak about the progress made thus far: the constitution gave birth to a beautiful child destined to grow and transform all the ideological, social, economic, cultural, spiritual and political aspects of our Kenyan society.

The ultimate goal of this transformation would be to replace the neocolonial status quo with a free, just, equitable and egalitarian, peaceful, prosperous, ecologically safe and democratic society. Such a society would form the basis on which to hold a national discussion of its weaknesses and, based on this dialogue, consequently build a firm foundation for yet another, better society, at which point it would come as no surprise if another new constitution were to be promulgated.

We the people of Kenya, having created the constitution, not only imposed it on the ruling elite but we then proceeded to hand over the baby to the same elite—a political leadership of child and body parts traffickers—to bring it up. A progressive constitution requires a progressive political leadership for its implementation.

The struggles of constitution-making do not end with its promulgation. Its implementation continues the struggles between the anti-constitution forces and those forces that call for its robust implementation and, as we approach the tenth anniversary of the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution on 27 August 2020, the struggle for its implementation continues unabated.

Genesis of the Struggle

The independence constitution gave birth to a neocolonial system that ensured the colonial state remained intact. Indeed, under that constitution, the multi-racial and multi-ethnic ruling elite continued to protect foreign interests, including the British colonial powers that never left Kenya. Therefore, it is not surprising that the independence constitution was resisted right from the time of its promulgation.

The opposition party, the Kenya People’s Union (KPU), opposed the neocolonial status quo. Both Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s book, Not Yet Uhuru and Bildad Kaggia’s The Roots of Freedom chronicle this fact. Both authors were founding members of KPU. Underground political formations such as The December Twelfth Movement and Mwakenya, and their publications Mwunguzi, Cheche, Pambana and Mpatanishi, also resisted the neocolonial state and its policies.

The so-called Second Liberation movement was premised on the repeal of Section 2A of the constitution that decreed the supremacy of one-party dictatorship. The movement also sought to have a constitution that would be aligned to the promise of a multi-party democracy while civil society organisations and opposition political parties continued the struggle for a new constitution. When the Moi-KANU dictatorship was defeated in 2002, the Kibaki-KANU-NARC dictatorship could not resist the people’s clamour for a new constitution and the 2010 Constitution was promulgated on 27 August 2010.

Gains and Challenges

The vision of the 2010 Constitution makes clear the rejection of the neocolonial status quo and affirms the supremacy and sovereignty of the Kenyan people as those with the powers to recall their representatives in parliament. The constitution provides for gender equity and equality and reiterates that the three arms of government derive their authority from the people. It promotes a political leadership comprised of men and women of integrity and national institutions that are independent and whose authority is derived from the people of Kenya. The constitution eschews the politics of division and calls for institutionalised, de-personalised, and democratic political parties, signaling the end of 47 years of gross electoral injustices.

We have a progressive Bill of Rights running the whole gamut of political, civil, economic, social, and cultural rights: decentralisation and democratisation of the imperial presidency to devolution; holding institutions, particularly those in finance and security, accountable to the power of the constitution; equitable distribution of national resources; the protection of land, our major resource, through the reduction to 99 years of the duration of leases given to foreign interests and the creation of a new land law regime that is communitarian to co-exist with a tenure system under which land is commodified (the co-existence of the two land tenures systems is envisaged as a strategy to build a future system that is based on access and use of land to all).

The neocolonial status quo served strong, dangerous, greedy and corrupt foreign and national interests that saw the promulgation of the 2010 Constitution as an inconsequential hiatus. This position has been resisted, reflecting the continued struggles for its implementation which has seen both progress and retrogression. Firstly, the imperial presidency has not been fully democratised and decentralised. Its restructuring has been resisted. It continues to oversee opaque sovereign debts and corruption and, against the provisions of the constitution, continues to maintain the colonial and neocolonial machinery of violence. Both the Treasury and the security apparatus are still departments of the imperial presidency contrary to the decrees of the constitution. And nor has there been consistent support for devolution from the imperial presidency and some institutions have become less independent while others have become moribund. No strong checks and balances exist.

We have witnessed the return of intra-elite struggles christened with various monikers: Tanga Tanga, Kieleweke, Tinga Tinga, Manga Manga, BBI, Dynasties, Hustlers. These struggles portend possible violence during the elections in 2022. They are also a reflection of a ruling elite that has maintained the politics of division (ethnic, religious, gender, generational, regional, clan, class, occupation and race) and that is extremely callous in its politics of inhumanity. It is an elite that continues to act as the loyal comprador class of foreign interests in the West and East. The forces massed against the implementation of the constitution are headquartered in the bosoms of the Kenyan elite.

Devolution has engendered in Kenyans the belief that resources will be shared equitably, that Kenya will become peaceful and stable, and that projects of state-building and nation-building will be strengthened. Under devolution, baby steps have been taken towards ending the marginalisation of certain counties and communities. In some counties, the sharing of state power with the grassroots through public participation has taken place and in others the leadership has resisted corruption.

Although the jurisprudence on Chapter 6 of the Constitution (Leadership and Integrity) is yet to be settled in the Supreme Court, we have witnessed progressive jurisprudence on the protection of devolution as well as on the implementation of the Bill of Rights (in particular political, civil, housing, evictions and public interest litigation) and on the overall protection of the independence of the judiciary.

We have seen attempts by the imperial presidency and parliament to thwart this positive trend by starving the judiciary of funds. Court orders have been disobeyed, weakening the constitution and the rule of law. Both the imperial presidency and the neocolonial parliament still believe that national resources belong to them and that—as those who hold the taxpayers’ money in trust—they are not accountable to the people from whom both institutions derive their powers.

We have also witnessed robust protection of the constitution from civil society groups, both in the middle class and at the grassroots. We have seen the emergence of movements that are calling for alternative leaderships at the helm of the movements of transformation and political parties. We have also heard the clarion call that “We do not want reforms from the current political leadership; We want the political power to carry out authentic reforms. We are now the authentic people’s opposition”. The emancipatory spirits of Mau Mau, the independence movements, the movements against neocolonialism, Saba Saba and Limuru have been resurrected. In all these movements, the centrality of the Kenyan youth is visibly signaling new political demands from those who have been marginalised by the system.

Coronavirus: Breath of New Life into the Struggle?

Indeed, the pandemic has provided a great opportunity to continue the struggle for the implementation of the 2010 Constitution. I believe the pandemic has brought with it the answer to the ever-present political question in Kenya: Who are the friends and who are the enemies of the Kenyan people?

The pandemic has further exposed the inhumanity of the state and the elite political leadership by their actions during this crisis: extrajudicial killings; demolition of the housing of the poor in Kariobangi Sewerage and at Ruai; disobedience of court orders in regard to the pandemic; refusal to take steps to progressively bring about the realisation of the public good under Article 43 of the Constitution (food, water, education, social security, health, sanitation); and, with the exception of two, a lack of response through social justice philanthropy from the billionaires and multi-millionaires and their infamous foundations.

If any evidence were needed to show how uncaring our state and the ruling class are towards the majority of the population, it is in their demands that the poor wash their hands while failing to provide them with soap and water using the resources that they hold in trust for the people.

To oppress the poor for not wearing masks was callous in the extreme, while lockdowns and curfews became death sentences for those who had no food and those looking for casual jobs to survive. No resources were committed to implementing the right to health for all. Indeed, all we heard were the familiar tales of corruption as the pandemic provided the elite class with another opportunity to indulge their unquenchable thirst for theft and debts.

One positive effect of the pandemic has been to hasten the national discussion on the formation of alternative political movements and leaderships. Many virtual meetings and launches have been convened, events ironically made possible by the very tools developed by surveillance capitalism.

Alternative transformative movements are growing in strength. Embryonic alternative political parties exist, their mobilisation and organisation energised by the pandemic. The merger of these movements and political parties is no longer an abstract idea and, as they move in from the margins, the old normal of before the pandemic—which was neither acceptable nor sustainable—is no longer guaranteed a further lease of life.

Indeed, the pandemic has breathed some life into the struggles for the implementation of the constitution. Calls by the elite to change the constitution have been met with demands to tekeleza katiba, implement the constitution. The good news to me seems to be that this herculean struggle will result in the baronial narrative that has gone unchallenged for the last 57 years facing the resistance of strong counter-narratives. Ironically, it is these counter-narratives, these alternative movements and political leaderships that will protect the baronial elites from themselves and their politics of revenge, and guarantee the national peace that the elite have shown themselves to be incapable of providing.