Epidemiologists measure how a disease spreads through populations using the basic reproduction number, otherwise known as R0 (pronounced “R naught”). Typical seasonal flu has a reproductive number of 1.2, while that of COVID-19 is reported to be approximately 2.5.

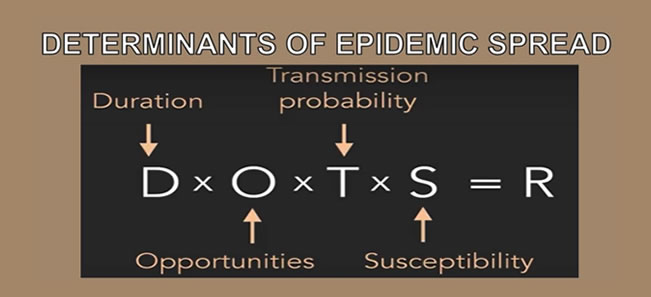

R = Reproductive number: How many people a given patient is likely to infect. If the reproductive number is greater than one (R>1), each case on average is transmitting it to at least one other person. The epidemic will therefore increase. Reproductive number is affected by factors including but not limited to population density, environment, age and immunity.

Typical seasonal flu has a reproductive number of 1.2; Spanish flu has a reproductive number of 2-3, while COVID-19 is reported to be approximately 2.5.

From a policy planning perspective, it offers a very clear objective: Reduce the reproductive number to less than one (R<1)

D= Duration: How long someone is infectious. If someone is infectious twice as long, then that’s twice as long as they can spread the infection. For COVID-19, people are infectious for up to 21 days. This can usually be reduced by treatment but there is currently no approved treatment for COVID-19.

O= Opportunity: The number of contacts of the infected person during the duration of the infection. If people are isolated (no contacts), then community spread does not occur or is minimised. This is achieved through social distancing.

T= Transmission Probability: The chance an infection is spread to a contact, hence the need to eliminate physical contact and hand washing.

S= Susceptibility: The chance a contact will develop the infection and become infectious themselves. We are all susceptible to COVID-19. Susceptibility is usually taken care of by vaccines, which we do not have for COVID-19.

Another important number for understanding diseases is the Case Fatality Rate (CFR): What percentage of people who have a disease die from it? On one extreme, we have rabies, which has a 99 percent fatality rate if untreated. On the other hand, is the common cold, which has a relatively high reproductive number but is almost never fatal. At the time of writing this, the crude case fatality rate for COVID-19 was 5.3 percent. I am calling it crude because thus far, testing has been selective. If testing protocols were to be expanded, this value will probably drop to 1 percent or less. But we will, however, work with the worst-case scenario for now.

In the case of the COVID-19, exponential growth will occur in the disease rate in humans as long as there is at least one infected person in the population pool, regular contact between infected and uninfected members of the population occurs, and there are large numbers of uninfected potential hosts among the population.

Which brings us to the term ‘doubling time’, which just means in this situation that cases/deaths will double in a given amount of time. Doubling rate in the United States of America has been reported to be three days, while China has managed to spread it out. And if the numbers from China are to be believed, they are now at six days. The longer the doubling time, the better.

One last terminology I will touch on is Herd Immunity, which simply means when a significant part of a population has become immune to a disease agent, its spread stops naturally because they are not enough susceptible people for efficient transmission. For COVID-19, immunity would come through getting the disease, assuming that it confers life-long immunity.

So what strategies do we have?

Do nothing

Based on the data we have from other countries, the reproductive number of COVID-19 is 2.5. That means, the population of people that will be infected to achieve herd Immunity is: 1-1/R0, equal to 60 percent. This translates to more than 28 million Kenyans getting it. Moreover, 80 percent (approximately 22 million people) of the population will have a mild disease or be asymptomatic. Another 14 percent (approximately 4 million people) will be in severe condition and may need hospitalisation, while 6 percent (approximately 1.7 million people) of Kenya’s population will be critical and may need intensive care facilities.

Going by case fatality rate of 5 percent, it means approximately 1.4 million Kenyans will die if we do nothing. I chose to stick with the global case fatality rate of 5 percent because even though we have a youthful population, we grapple significantly with both communicable – AIDS, Tuberculosis, malaria, pneumonia etc., and non-communicable illnesses. Furthermore, a majority of the population lives in squalid conditions and is prone to other competing illnesses. And to add salt to injury, as a country, we are still battling malnutrition and anaemia.

Doubling of new infections in the United States of America is happening every three days. This means the numbers will double ten times in a month. Though we have yet to reach the exponential phase, a quick back-of-the-envelope analysis places Kenya, with its current infection rate at 122, indicates the number of people with COVID-19 will double ten-times one month from today. The numbers will be compounded the longer we do nothing and the effects will be fatal to say the least.

Do something

Since there are no antiviral medications for COVID 19 and no vaccine, we must rely on non-pharmaceutical interventions like social distancing and eliminating physical contact.

The impact of early and widespread social distancing is flattening the curve. The flattening minimises overwhelming the healthcare facilities and their resources, which is good in the short run, but lengthens the duration of the epidemic in the long run. If the health system becomes overwhelmed, the majority of the extra deaths may not be due to coronavirus but to other common diseases and conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, trauma, bleeding, and other such diseases that are not adequately treated.

Too, if large numbers of Kenyans were to get very sick and start flooding into hospitals and health care facilities, our system will undergo a severe stress test. Our health system could be overrun in a very short period of time. Thus, figuring out how to plan for a massive influx of patients is one of the hardest parts of preparing for health emergencies, and it has yet to be adequately dealt with in Kenya.

If large numbers of Kenyans were to get very sick and start flooding into hospitals and health care facilities, our system will undergo a severe stress test. Our health system could be overrun in a very short period of time.

“Surge capacity” management is one of our biggest weaknesses, particularly at a time when we have shortages of health workers, and a weak supply chain management system. The national and county governments have spent very little on health care, choosing to focus on capital expenditure where there is something for them to ‘’eat’. Even in the course of this pandemic, health care workers are being appreciated by word of mouth but are not being protected, risking spreading this to patients, other workers, families as well as the public. The risk of COVID-19 being another nosocomial infection is very high. Indeed, the 3,000 unemployed doctors have yet to be absorbed into the healthcare system to mitigate this crisis, but I digress.

Mitigation

Here the focus is to slow the growth of the epidemic. Instead of having it double every three days, you put interventions in place to slow it down to double every seven days. This will ease the demand for health care services and give you breathing room. Interventions here include hospital isolation of confirmed cases, home isolation of suspect cases, home quarantine of those living in the same household as suspect /confirmed cases, and social distancing of the elderly and others at most risk of severe disease.

This has the potential to reduce infections and deaths by as much as 60 percent, and prevent the economy from collapsing completely the numbers will drop from 28 million infections with no mitigation, to approximately 11.2 million, and 560,000 deaths if we infer to the case fatality rate of 5 percent.

Suppression

With suppression, you want to reduce the reproductive number to below 1, hence stopping transmission. This is what we are doing now. Travel restrictions, social distancing, school closures, curfews, stopping mass gatherings. The only strategy that we haven’t adopted so far is sheltering in place, what people like to refer to as lockdown. The problem with this strategy is that it has enormous economic and social impacts. And as long as we live in a global village, there is a great risk of recrudescence especially when you open the borders. This means you have to maintain the strategies until a vaccine is discovered and you have vaccinated at least 60 percent of the population, or at least until a cure is found. We are probably 6-12 months away from a solution considering how clinical trials are being fast-tracked. There is the option of relaxing the strategies occasionally when the reproductive number is low, but this means you must have a meticulous method of disease surveillance to pick up recrudesce early.

How do we balance public health vs. economic consequences?

The bubonic plague of medieval Europe, the Spanish flu of 1918, SARS, H1N1 Swine flu and other infectious diseases have shaped the political economy of the world and so far, all evidence indicates that COVID-19 will do the same.

We must, now, grapple with philosophical issues such as how much economic value we are willing to lose to save a human life.

As a public health practitioner, I decree that saving life is more important than social and economic effects. I think there must also be a delicate political balance to be considered and policymakers should reflect whether they are doing more harm than good.

When making decisions, policymakers often use what’s called the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL) to set an upper bound on how much you can impose on people in order to save lives. But if policymakers assigned an infinite economic value to each life, they would spare no expense and be fearless in imposing any inconvenience.

Information

At a time when everyone needs better information, from disease modelers and governments, we lack reliable evidence on how many people have been infected with COVID-19. Better information is needed to guide decisions and actions of monumental significance to monitor their impact.

The data collected so far is unreliable. Given the limited testing to date, some deaths and probably the vast majority of infections due to COVID-19 are being missed. We can’t access if we are failing to capture infections by a factor of three or 300.

As a public health practitioner, I decree that saving life is more important than social and economic effects. I think there must also be a delicate political balance to be considered and policymakers should reflect whether they are doing more harm than good.

Too, we don’t know what factors are being modeled. Kenya, for instance, is a diverse country with densely populated counties like Nairobi, and less densely populated like Turkana. A one-size-fits-all model won’t work. The modeling models developed need to be county-specific, and interventions need to be more nuanced and contextual. Of course, the chain of command should remain at the ministry of health but with an aggressive inter-governmental coordination prescribing strategies for each county.

This is the time to fully implement the spirit of the 2010 constitution and bring in the devolved units, as health is a function of counties. It is here that strategies such as how will “sheltering in place” work for pastoralism communities be enforced? What strategies need to be considered for the rural areas where the majority of their populations are the elderly?

The overarching idea is to tailor-make a range of policy mixes suitable for the Kenyan context.

Is Kenya getting right?

Based on the numbers I have shared above; I would say it’s a mixed bag. Social distancing is yielding fruit, however, we need a scientifically determined threshold on when these can be relaxed or re-introduced. Indeed, there must be a robust health surveillance system in place, which has to be county-specific. The success of the ongoing strategies to mitigate community transmission will depend on how Kenyans collectively respond to the plea of physical distancing and hygiene.

Still, we have to do more. First, we are not testing enough. I posit that we should partner with certified private laboratories to scale-up testing. We must acquire testing kits that can be used on Genexpert platforms that were provided by PEPFAR and are available in all counties.

I can’t emphasise enough about testing.

You test, isolate and trace to minimise community spread. Without this, we are swimming blind. Secondly, we are not protecting our health care workers. They are the first-line workers and are at the greatest risk of acquiring COVID-19, transmitting it to other patients, as well as to the community.

Finally, there hasn’t been a pandemic control that has succeeded without social capital. How Kenya and Africa will deal with this pandemic will squarely depend on the strength, resilience and adaptability of our social capital to weather the storm.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here belong to the author, and do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the MOH or other bodies involved in COVID-19 response.