The economic management space has become rather lively of late. A few weeks ago, the National Treasury published an updated national debt register that spooked quite a few people. A couple of days later, it circulated a draft debt policy for comments in whose wake followed a stern memo from State House to all state agencies. The subject of the memo was austerity measures and the following three directives were addressed to state corporations: “(a) to immediately remit the entirety of identified surplus funds to the National Treasury; (b) to assign (transfer ownership) of all the Treasury Bills/Bonds currently held in the name/or for the benefit of the State Corporations/SAGAs to The National Treasury, including any accruing interest by Friday, 15 November 2018; (c) to remit the entirety of Appropriations-in-Aid (AiA) revenues to The National Treasury”

SAGAs stands for Semi-Autonomous Government Agencies. Appropriations-in-Aid is the money that government agencies raise from the public, usually in fees; court fines, licences and payments for services. This money is usually factored into their budgets—for instance, if an agency’s approved budget is Sh1 billion and it expects to collect Sh200 million, the Exchequer will budget to fund the balance of Sh800 million.

It turns out that this memo was the agenda of the event at which Uhuru Kenyatta made his “why are Kenyans broke?” faux pas. Evidently, he had summoned the state corporation bosses to read them the riot act on the directive. Hot on the heels of the State House meeting, it was reported that Parliament had passed an amendment to the Public Financial Management Act requiring that all public agencies centralise their banking with the Central Bank of Kenya.

Why the sudden zeal?

The answer may be found in a press release issued by the IMF on 22 November disclosing that the Fund had concluded a visit to the country to review recent economic developments. It also disclosed that another visit was planned for early next year “to hold discussions on a new precautionary stand-by facility.” A precautionary standby facility is a credit line that IMF member countries can draw on in the event of a shock that affects a country’s ability to meet its external payment obligations, for example, a petroleum price shock, or a global financial crisis of such severity that a country’s foreign exchange resources would not be sufficient to cover both imports and debt servicing.

The previous standby facility, which was due to expire in March 2018, was suspended in the run-up to the 2017 general election because of non-compliance. In early 2018, the administration sought and secured a six-month grace period during which it would negotiate a new one (with no money available during the grace period as the government was not compliant). The grace period was to expire in September, but in August the talks collapsed. Some of the conditions that the IMF sought were the removal of both the interest rate cap and the controversial VAT on fuel. The exchange rate policy may have been another sticking point, as the IMF claimed that the government was artificially propping up the shilling, a contention that the Central Bank has vigorously contested.

It turns out then that the sudden flurry of activity may be all about impressing the IMF. Indeed, the centralisation of government banking—known as the Treasury Single Account (TSA)—is one of the IMF’s latest fads, And just as with IFMIS before it, TSA is supposed to be the silver bullet that will put an end to financial control woes.

There are at least two other developments that are consistent with the sort of demands that we can expect from the IMF.

First, the government has started to make wage bill noises again. The acting Treasury Cabinet Secretary was heard to lament at a conference convened to discuss the wage bill that it is consuming 48 per cent of revenue, way above the maximum of 35 per cent stipulated in the Public Finance Management Act. This appears to be a case of giving a dog a bad name. The total wage bill for the entire public sector including commercial enterprises was Sh600 billion, about 40 per cent of national revenue. But even this is misleading because commercial parastatals (Kenya Pipeline, Kenya Airports Authority, Central Bank, etc.) do not depend on government revenue. The consolidated public sector wage bill as a percentage of consolidated revenues is in the order of 34 per cent. This is not the first time that the government is cooking the wage bill figures.

It has also been reported that Kenya Power has applied for a 20 per cent tariff increase, in part to cover for the national government subsidy for low-income consumers. The IMF takes a dim view of subsidies of this kind and although this has not come into the public domain, I would expect the IMF to similarly take a dim view of the operational subsidy made to the SGR, which is even less defensible than the tariff subsidy.

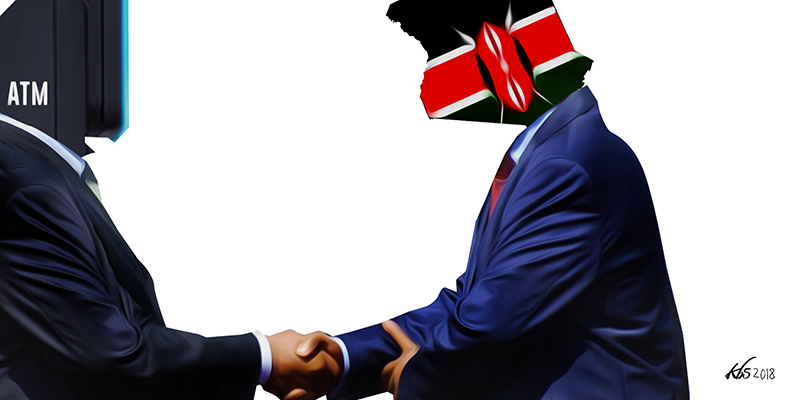

Given that the same Jubilee administration that found IMF conditions unpalatable last year now appears to be bending over backwards to secure a deal, we are compelled to ask: what has changed?

Money is short. This year the government plans to borrow Sh700 billion. It plans to borrow Sh450 billion domestically, and Sh250 billion from foreign sources. Soft loans from development lenders are budgeted at Sh50 billion, leaving the balance of Sh200 billion to be sourced from commercial lenders, either by way of issuing sovereign bonds (Eurobonds) or by arranging syndicated bank loans. The Sh200 billion foreign borrowing is “net”, that is, over and above what the government will borrow to pay the principal installments on foreign bank loans (e.g. the Exim Bank of China SGR loans), and to refinance or roll-over maturing syndicated loans (thankfully, there are no Eurobonds maturing this year) amounting to Sh131 billion, bringing the total borrowing to Sh331 billion. As a rule, interest payments are paid out of revenue while the government aims to pay the principal by rolling-over or refinancing.

The government has access to three potential sources of this kind of money: budget support (also known as programme loans, issued by multilateral institutions, including the IMF itself), Eurobonds and syndicated loans. Of the three, the multilateral lenders are the cheapest, but they take long, come with conditions and usually require that an IMF programme be in place (although last year the World Bank did extend a programme loan without one).

Eurobonds are the next best option. The Government does not need an IMF deal to go to the sovereign bond market. Indeed, it did not have an IMF programme in place during its previous two bond issues: the debut issue in 2014 and the second one in February 2018. But circumstances do change. With as many as 20 African countries either already in or at high risk of debt distress, it may be that the market has signaled to the government that an IMF stand-by would be “an added advantage.” Indeed, the IMF itself has downgraded Kenya’s debt distress risk from low to medium.

Multilateral lenders are the cheapest, but they take long, come with conditions and usually require that an IMF programme be in place

For what it’s worth, the Jubilee administration is finally owning up to the fact that its finances are in a worse state than it has previously cared to admit. The new narrative heaps the blame on the now-suspended Treasury officials, Cabinet Secretary Rotich and Permanent Secretary Kamau Thugge. I was taken aback recently when a cabinet secretary who has a strong background in finance remarked that they were not aware how bad things were until Rotich and Thugge were booted out, while the central bank governor has been quoted blaming Rotich’s rosy revenue forecasts—which he has characterised as “abracadabra”—for encouraging the government to pile up debt. This is disingenuous because that is not how it is done. The borrowing is decided politically first, and then they cook the revenue numbers to show that we can afford it. The Governor has been part of the racket. It is also mean to mock one’s colleagues when they are in trouble, not to mention that the Central Bank has been deeply implicated in the Eurobond fraud cover-up under his watch. The Governor’s turn to be thrown under the bus may yet come, but I digress.

What is now inescapable is that six years of the most egregious fiscal profligacy has caught up with us. As this column argued a fortnight ago, the government is now hostage to fate—it can kick the can down the road and hope and pray that the crunch does not come this side of the election, in which case an IMF facility seems like a good cushion to have. But it comes with a health warning: the cure may be worse than the disease.

A couple of weeks ago, Lebanese people took to the streets and brought down the government in what has been dubbed the Whatsapp revolution. Those of us who are a bit long in the tooth remember Beirut as the byword for urban warfare. Lebanon’s sectarian warfare ended when its fractious and venal political elite worked out an inclusive eating arrangement of the kind that our equally venal eating chiefs are now crafting with handshakes, bridge building and whatnot. With no agencies of restraint, the chiefs finished the tax money and progressed to eating debt, chomping their way into a 150+ per cent of GDP debt (third highest in world after Japan and Greece) that is consuming half the government revenue in interest payments alone, and causing economic stagnation.

What is now inescapable is that six years of the most egregious fiscal profligacy has caught up with us

On its knees, the government passed an austerity budget in July. The austerity budget coincided with an IMF mission which recommended “a credible medium term fiscal plan aiming for a substantial and sustained primary fiscal surplus.” Primary fiscal balance is the difference between government revenue and recurrent expenditure excluding interest. It is achieved by raising more taxes and cutting wages and O&M (operations & maintenance) spending. These cuts usually fall most heavily on social spending.

As the government set about imposing more austerity and raising taxes, it unveiled a tax on voice-over-IP (VOIP) calls in October, the idea being to protect tax revenue from regular voice calls. It was the last straw. Evidently, the eating chiefs had not realised that this was the social lifeline for the youth. The people took to the streets. Two weeks later, the government fell. Lebanon is now in full financial meltdown. The IMF is nowhere to be seen.

Mozambique had an IMF programme in place when it ran into debt payment difficulties that forced the government to disclose more than a billion dollars of secret “Tuna bonds” debt. Now, the purpose of an IMF programme is to help a country in payment difficulties, but because the secret debt violated the terms of the IMF deal, instead of bailing Mozambique out, the IMF led the other donors in suspending aid to the country. Instead of helping put out the fire, the fire brigade decided that teaching the culprits a lesson was more important than saving the victims. Mozambique’s economy went into free fall, where it remains. This is the very same IMF that cooked our books to cover up the Eurobond theft.

The borrowing is decided politically first, and then they cook the revenue numbers to show that we can afford it

What alternative does Uhuru Kenyatta have? In economics, we talk of the orthodox and heterodox approaches to dealing with a sovereign financial crisis.

The orthodox approach is a formulaic one-size-fits-all approach which adheres to one economic school of thought known as neoclassical economics. Its prescriptions are fiscal austerity and doctrinaire free market ideology. It is, as is readily apparent, the IMF prescription. Heterodox is another name for unorthodox, and refers to a pragmatic strategy that draws from the entire spectrum of economic ideas from Austrian to Marxist political economy and everything in between.

The dilemma governments have to face is that the orthodox cure is sometimes worse than the disease, but it’s the one with the money behind it. Heterodox approaches work better, but they require a resolve and an imagination that many governments are unable to muster, especially when they have their backs against the wall.

Can the Jubilee administration muster the resolve for a heterodox response? Doubtful.

Four years ago I contemplated the Jubilee administration ending precisely where it is headed, to wit: “I cannot think of a more fitting epitaph for the Jubilee administration’s reign of hubris and blunder, plunder and squander, than the rest of the term spent savouring copious helpings of humble pie in an IMF straightjacket. Choices do have consequences. Sobering.