If all goes according to plan, construction work on a 61-storey skyscraper – which is being mooted as the tallest structure in the whole of Africa – will soon start in Watamu, a sleepy fishing village and tourist resort about 20 kilometres south of Malindi along Kenya’s coastline.

But lack of clarity on how the developer managed to get approval for the Sh28 billion ($280 million) project is raising concerns about whether this is another white elephant or phantom project. Questions are also being raised about whether the building is economically feasible and environmentally sustainable.

On its website, Palm Exotjca is marketed as an exclusive development with “chic residential suites, premium commercial space, eclectic restaurants and a vibrant casino”. Three Italians are said to be managing the project: The chairman Giuseppe Moscarino is a veterinarian and neurosurgeon from Rome whose passions are “art, architecture and Africa’s extraordinary beauty”; the managing director is Oliver Nepomuceno, who is described as the manager of several commercial and investment companies and joint ventures; and Lorenzo Pagnini is listed as the lead architect.

The main investors in the project are said to be the Italian billionaire Franco Rosso, along with investors from Switzerland, Dubai and South Africa. According to the developers, an engineering firm in India will handle the structural design aspects of the building while a Chinese company will undertake the construction work. Local engineering and architectural firms will also contribute to various aspects of the construction phase.

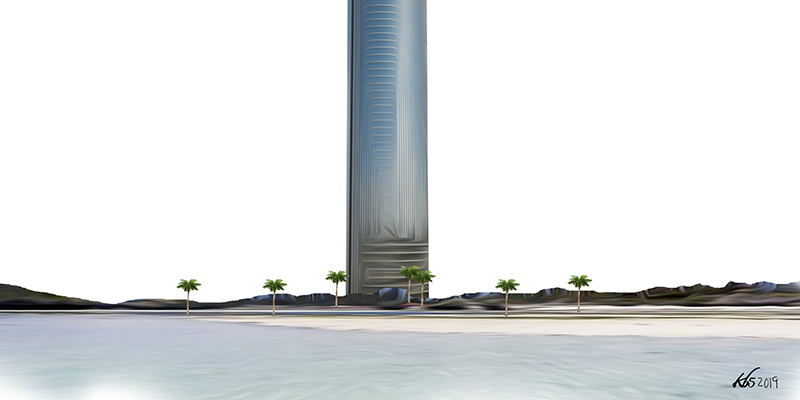

When completed, the 370-metre-high building, whose shiny artistic exterior will resemble the trunk of a palm tree, will comprise 270 hotel rooms, 189 luxury suites and apartments and social amenities, such as a shopping mall, a business centre, a theatre, a cinema, a nightclub, a fitness centre, a wellness spa, a children’s play area and four swimming pools – all of which invoke images of Dubai or Las Vegas.

The problem is that Watamu is not Dubai or Las Vegas. This fishing village and beach resort with a population of 14,000 barely has the infrastructure to service a level 4 hospital, let alone a skyscraper of this size. MAWASCO, the water utility company, already has problems meeting the water demand in Watamu and there are no signs that it intends to increase supply during the construction phase of the project or when it is completed. The Kenya Power and Lighting Company has promised to upgrade the Kakuyuni sub-station with a 23 MVA transformer and 25 kilometres of an overhead line, but only on the condition that the developer pays for the upgrade, which will cost Sh161 million.

Moreover, Watamu is hardly a vibrant tourist destination and commercial hub along the lines of Rio de Janeiro or Miami. What were the developers thinking when they came up with the idea and how do they expect to fill up all these hotel rooms and apartments?

Other such projects, such as Flavio Briatore’s Billionaire Club in Malindi – which was marketed as “a club for the world’s richest” – also had ambitions to attract the wealthy from around the world, but Malindians have yet to see Bill Gates or the Saudi Prince Mohamed bin Salman check in. On the contrary, Briatore has threatened to sell his other hotel, Lion in the Sun, in Malindi because he says that the unattractive business environment and poor infrastructure in the town are keeping foreign tourists and investors away.

In an article published in Coastal Guide, Issue 20, July 2019, Damian Davies, the general manager of the Turtle Bay hotel in Watamu, questioned the viability of the Palm Exojca project and whether the investors will get a profitable return on their investment. “There are lots of properties for sale in Watamu that aren’t selling; who will buy an apartment in a tower some distance from the beach when no one is buying beautiful beach properties?” he asked. “We don’t want a start-up that for economic reasons isn’t finished: a partially completed skyscraper.”

Red flags

Malindi and Watamu are currently experiencing a slump in tourism. Hotels are either shutting down or scaling down.

Many Italian residents are selling their villas to go back to Europe or to move elsewhere. But there is simply no market for these properties. Those that do manage to sell their houses often do so at below-market rates, mainly to Kenyans from Nairobi looking for a holiday home.

Italian and other tourists are flocking to other destinations in East Africa, such as Zanzibar, which have not been tainted by the threat of terrorism, and which have more superior amenities and infrastructure. The idea that this luxury development will be the magnet that will pull in tourists and foreign investors could simply be wishful thinking.

At a public participation meeting organised by NEMA at the site of the building on 3 October, Mr Moscarino, the chairman of Palm Exojca, explained that this exclusive development will bring another type of high-end visitor to the area and is not competing with the hotels in the vicinity. He added that he was very proud to be associated with the tallest building in Africa.

However, let us say that the project is viable and there is a market for it, this question still remains: Why build such a tall structure in a village that is not a commercial hub and where most buildings are just one-storey tall? Wouldn’t it be incongruous with its surroundings? Wouldn’t it be like building a skyscraper in the middle of a desert? If you have to build the structure, why not build a scaled-down version?

The answer perhaps lies in the fact that skyscrapers are more about ego and prestige than about economics. Very tall structures, such as the Petronas Towers in in Kuala Lumpur and the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, are a kind of phallic symbol representing strength and virility. The skyscraper is to the modern world what the obelisk was to the ancient Egyptians – a monument that projects mystical power and status. But is this what Watamu needs?

Kilifi County has given the go-ahead to the project perhaps in the belief that it will generate jobs and stimulate the local economy, but Najib Balala, the Cabinet Secretary for Tourism, is not convinced that this is the kind of project that Watamu requires. He feels that a more suitable location for the project might have been Mombasa or Nairobi. He has also advised the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) not to approve the project. “That 61-storey skyscraper on a small plot in Watamu must not be built,” he is reported to have said.

What raises a red flag is the fact that the Palm Exotjca website lists its address as One World Trade Centre, Suite 8500, New York, but that address seems to be a virtual one intended to impress high-end clients. The other address is a plot number and P.O. Box number in Mombasa, but there is no email or phone number provided. The phone number listed on the website is a Washington DC number that goes unanswered. One concerned resident who has been following up on the matter said: “When we call the phone number listed on the website, no one answers it and has not for over a year. So why is it so difficult to find the real phone number if Palm Exotjca really wants to sell high-end apartments?”

According to residents’ associations and other concerned groups in and around Watamu who have raised their objections regarding the project with NEMA, Vitamefin Limited, the company that is listed as the owner of one of Palm Exojca’s plots in Watamu, was previously registered in the US Virgin Islands. However, the Virgin Islands Official Gazette, Volume XLIX, Number 78, shows that this company was struck off the register of companies on 1 May 2015 for non-payment of annual fees.

NEMA says that it has conducted an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) that shows no adverse environmental or social impacts related to the project. But Augustine K. Masinde, the National Director of Physical Planning in the Ministry of Lands and Physical Planning, disagrees. In a letter to the Director-General of NEMA dated 12 July 2019, he raised concerns about the conformity of the proposed development with physical planning laws and zoning regulations. He also said that certain issues, such as the environmental suitability of the parcel of land for the proposed development and availability and adequacy of requisite infrastructure and services, needed to be clarified. “In view of the foregoing, we advise that you suspend the approval of the proposed development to allow proper review and audit to establish its sustainability,” stated the letter.

A memo to NEMA – submitted on 21 July this year on behalf of the Watamu Association, the Kilifi Residents Association, the Kilifi County Alliance, Watamu Hoteliers, Local Ocean Trust, Watamu Marine Association, A Rocha Kenya, Watamu Against Crime, Watamu Property Managers and the Jiwe Leupe Community Association – lists several problems with the project, including:

- The project is disproportionate in scope and scale, both technically and financially. The substrata along the Kenyan coast is highly unsuitable for very tall buildings.

- There has been lack of meaningful public participation by the developers and the ESIA team.

- Watamu lacks the skilled labour force to put up such a structure. The immigration of a large, well-paid skilled workers into Watamu has the potential for significant social, cultural, economic and moral hazards.

- The area lacks the required infrastructure, including water and electricity supply, for such a large-scale project.

Lack of sufficient and meaningful public participation is of particular concern to the residents, as it was with the proposed coal-fired plant in Lamu. In the case of Lamu, lack of public participation was a key consideration in the National Environment Tribunal (NET)’s ruling. In its 26 June 2019 jugement, NET ordered Amu Power, the key player in the proposed Lamu coal project, to halt construction of the plant and to undertake a fresh ESIA for the project. It noted that the ESIA carried out for Amu Power was flawed in one key aspect: it did not involve public participation, which is a constitutional requirement. It noted that lack of public participation was “contemptuous of the people of Lamu”.

Mike Norton-Griffiths, the chairman of the Watamu Association, says that the major flaw in the project is in the planning. He says that nine completely independent projects are buried in the ESIA, each requiring an ESIA and planning permission, and each needing to be completed before the main project. Yet this has not been done.

There are also serious environmental concerns. Watamu is home to the Arabuko Sokoke Forest, the famous Gede ruins and a marine park that is the breeding ground for turtles and other marine life. There are concerns that improper handling of wastewater and sewage from the project – both during the construction phase and when it is completed – could negatively impact the biodiversity in the region.

Simmering tensions

The above concerns were partially addressed on 3 October at the public participation meeting organised by NEMA, which I attended. A Kenyan engineer recruited by Palm Exojca made a detailed slide presentation explaining how the development will deal issues such as wastewater and even birds who could die accidentally by crashing into the tall shiny structure. (Much of this presentation was lost on the local communities attending the meeting, but that did not deter him from going on with the hour-long presentation.)

The meeting, which was attended by NEMA, county government officials, some representatives of residents associations, and a large group of people from the community, at times appeared stage-managed and intended to allay any fears that the project was unviable or environmentally unsustainable.

But what also came out loud and clear at the meeting was that the local residents view the project as a contest between the national government and the county government of Kilifi and between the (mostly British) expatriate community and the Italian investors. Speakers at the meeting emphasised that this was a project supported by the county government and that the national government should not interfere with it. “Those opposed to this project are enemies of devolution and enemies of the people,” said one very vocal community leader, whose statement was met with roaring applause from the audience.

Supporters of the project, including the governor of Kilifi County, Amoson Kingi, believe that the project will bring in much-needed jobs to the area and will boost tourism. Community members at the meeting repeatedly cited employment as the main benefit of the project. (The majority of the local residents will neither be able to afford the amenities offered at Palm Exojca, but they do hope to find low-paid and semi-skilled jobs in the luxury development.)

It is hard to argue with the sentiments of the majority of the local people, who have been marginalised for decades and who suffer from high levels of poverty and underdevelopment. (Kilfi County is among the six poorest counties in the country.) A project like this could change their fortunes in significant ways by generating hundreds of jobs both directly and indirectly. When you have not seen any real development in your area for years, despite the presence of a large numbers of beach hotels, a project like is hard to resist, even amid environmental concerns. As one speaker at the meeting pointed out, “Nobody talked about how the beach hotels in Watamu would affect turtles. So why should this development, which is not even on the beach (it is 366 metres from the ocean) be of concern?”

The project has also unveiled simmering tensions between the indigenous local residents and the largely British expatriate residents. Kilifi North MP Owen Baya, a vocal supporter of the project, claims that the British people living in Watamu are opposed to the project because it will “block their view of the ocean”. But he does not say how the influx of wealthy foreigners into Watamu when the building is completed will affect the local population. Will it give rise to other types of tensions?

There is also the issue of double standards. Someone I spoke with who did not want to be named told me that the Europeans living in Watamu live there only half the year; they spend the rest of the year in Europe. “These people can enjoy First World amenities, like theatres and nice roads and pavements, whenever they want to. But they want Watamu to remain a backwater whose unspoilt natural environment they can enjoy whenever it is convenient for them. But what about the locals who have never been to a cinema or even travelled outside their county? Don’t they deserve a taste of modernity?”

The locals clearly view the Italian investors as a godsend that will bring much-needed employment and development to the area. One MCA even referred to Mr. Moscarino as “our small God”.

“Even London began as a small village,” said another speaker. “We want Watamu to become a city like Dubai.”

Owen Baya, the Kilifi North MP, told the audience that until a hundred years ago even Nairobi was just a swamp, and wondered why there was so much resistance to this particular project.

At the meeting, Mr. Moscarino gained additional points with the locals when he sold the development as a social responsibility project. He told the cheering crowds that the developers will build a hospitality school and a secondary school in Watamu and that up to 2,000 local people will be hired as drivers, carpenters, construction workers and the like during the construction phase. It was obvious that he was exploiting the fact the majority of residents are too poor and illiterate to refuse such a generous offer. His statement was met with loud cheers.

As I left the NEMA meeting, I did wonder whether if, for any reason, the project is not completed – and the promised jobs and schools never materialise – what effect this will have on the local people. Will dashed hopes lead to even more resentment?

We can only wait and see if indeed the local people’s dreams will be realised in five years when the construction of Palm Exojca is expected to be completed. Palm Exojca could either be the catalyst that spurs development in Watamu or the Trojan horse that introduces vices that threaten to destroy a way of life. It could also be a case study in how economic opportunities often trump environmental concerns when it comes to “development”, especially in areas that are poor and marginalised.