Ever since it was pronounced as one of his “Big Four” legacy initiatives, Uhuru Kenyatta’s manufacturing agenda has been blurry but an extensive television interview given two weeks ago was very revealing; in a nutshell, it is protectionism. “We want to ensure that we protect our industries, work with our industries to ensure that they are competitive but we also encourage them not to take advantage and extort Kenyans by overpricing their products.”

Protectionism is a policy regime that puts tariff and other barriers on imports that compete with domestically produced goods. A simple definition of competitiveness is a company, industry or country that is able to produce goods and services that are comparable in price and quality with those traded internationally. Competitiveness is benchmarked against internationally traded goods and services. But the purpose of protecting domestic industries is to shield them from competition. Once they are shielded from competition, they do not need to be competitive.

Ever since it was pronounced as one of his “Big Four” legacy initiatives, Uhuru Kenyatta’s manufacturing agenda has been blurry but an extensive television interview given two weeks ago was very revealing; in a nutshell, it is protectionism.

We have a problem. A protected competitive industry is a contradiction in terms. Tea and sugar, two industries that have featured in this column on a number of occasions, provide a perfect case study.

As an export-oriented industry, the tea industry has to be globally competitive to survive. There is little the Kenyan government could do to help the industry if it was not able to produce quality tea at a price that its international customers are willing to pay. Consequently, there is no need to protect the local market from imported tea. Even though imported tea brands are available in supermarkets, they do not cause owners of domestic brands sleepless nights.

As an export-oriented industry, the tea industry has to be globally competitive to survive. There is little the Kenyan government could do to help the industry if it was not able to produce quality tea at a price that its international customers are willing to pay. Consequently, there is no need to protect the local market from imported tea. Even though imported tea brands are available in supermarkets, they do not cause owners of domestic brands sleepless nights.

Sugar is a different kettle of fish altogether. It is the country’s most protected industry. Kenyan sugar costs $800 per tonne ex-factory, against a global price of $280. The only way Kenya’s sugar industry can stay in business is by being heavily protected. For the last twenty years or so, the country has sought and secured safeguards from the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) so that the country can restructure the industry, to no avail.

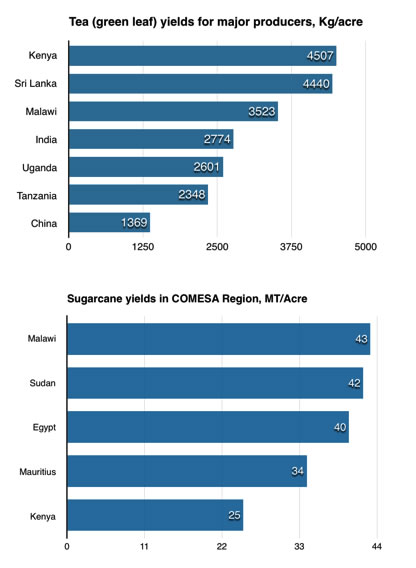

Why is Kenya’s tea globally competitive and sugar the complete opposite? Competitiveness is closely related to, and in fact, derives from productivity. Kenya has the highest tea farm productivity in the world, at about 4,507 kilograms of green leaf per acre, closely followed by Sri Lanka at 4,440. Unsurprisingly, Kenya and Sri Lanka are the leading tea exporters, each accounting for between 20 and 23 per cent of the world market. By contrast, of the COMESA trading partners, Kenya has the lowest sugar cane yields (see chart).

The only way Kenya’s sugar industry can stay in business is by being heavily protected. For the last twenty years or so, the country has sought and secured safeguards from the Common Market of Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) so that the country can restructure the industry, to no avail.

But the sugar cane yields are only part of the low productivity story. Kenya’s sugar cane also has less sugar content, and the state-owned factories are less efficient, i.e. they achieve lower extraction rates than those of the trading partners—low cane yields, poor quality cane, inefficient factories. To keep this industry alive, it is protected by a 100 per cent import tariff, or $460 per tonne, whichever is higher. At the price of $280 a tonne, the applicable tariff is $460, which is an import duty of 164 per cent.

Why are the sugar cane yields so low? We have the wrong model of sugar industry. Sugar cane is a capital intensive crop, that is suited to large-scale integrated farm and factory operations. Kwale International Sugar, which revived the failed Ramisi Sugar, reports obtaining 60 tonnes a hectare using a “state of the art subsurface irrigation system”. Smallholder farmers do not have the capital or knowhow to do this, and it probably would not make sense to invest in such systems on a small scale. Moreover, once the cane is planted, it requires very little labour until harvest time.

Tea, on the other hand, is a labour-intensive crop. It needs to be picked and tended meticulously by hand throughout the year. Smallholder tea farmers work in their fields every day. The economic law of comparative advantage predicts that a country’s competitiveness will reflect its factor endowments, that is, capital-rich countries will be competitive in capital intensive goods, and labour-rich countries in labour-intensive goods. Because we have relatively more labour than capital, the global competitiveness of our tea vis-à-vis the uncompetitiveness of our sugar reflects our comparative advantage.

Why are the sugar cane yields so low? We have the wrong model of sugar industry. Sugar cane is a capital intensive crop, that is suited to large-scale integrated farm and factory operations. Kwale International Sugar, which revived the failed Ramisi Sugar, reports obtaining 60 tonnes a hectare using a “state of the art subsurface irrigation system”.

It is instructive to compare sugar with coffee. Since the early 90s, Kenya has failed to reform the coffee industry to keep up with changes in the global market. Production and exports have plummeted from a peak 140,000 tonnes in the late 80s to just over 40,000 tonnes today. There is nothing that the Government can do to protect the coffee industry. It simply has to shape up or ship out. But the most important thing is that the resources that were producing coffee—land, capital and labour—have been redeployed to other products including macadamia nuts, avocado, dairy, bananas, real estate and so on.

The same would have happened in western Kenya if the sugar industry was not so heavily protected. The long-suffering smallholder sugar cane farmers would have long since switched to other products of which they would be competitive producers such as cereals, livestock, horticulture, oil crops and so on. Instead, protectionism misallocates 440,000 acres of some of Kenya’s best rain-fed agricultural land—a very scarce resource—to a crop that generates a mere $400 per acre, compared with tea, which generates $2,200 an acre.

Protectionists often bolster their case by observing, correctly, that the East Asian Tigers also protected their infant industries during the early stages. The best documented, and arguably also the most insightful case, is that of South Korea. South Korea’s industrialisation took place in two phases spanning two decades, 1955-65 and 1965-75. During the first phase, it pursued both import substitution and export promotion simultaneously, but with a heavy bias towards import substitution. By the early 60s it had run into the chronic balance of payments crises that have plagued all countries pursuing import substitution industrialisation through protectionism— including Ethiopia currently. The government realised that import substitution had hit a dead end, and changed course, as Larry Westphal and Kwan Suk Kim, of the World Bank and Korea Development Institute respectively, explain in their 1977 study, Industrial Policy and Development in Korea:

Policymakers came firmly to accept that rapid economic development depended upon an export-oriented industrialisation strategy. This view was predicated on the understanding that Korea’s natural resource base was very poor and on the realisation that further opportunities for import substitution were only to be found in intermediate and durable goods, where the limited domestic market could not justify establishing plants large enough to realize technological economies of scale.

The Koreans then embarked on trade liberalisation, devaluation and other policy reforms that the rest of the developing world was to adopt two decades later, and that we now call structural adjustment. These reforms were implemented between 1961 and 1964. Export-led manufacturing took off. By 1975, manufactured goods contributed a third of the GDP, and 75 per cent of exports.

As noted, Korea’s industrial policy pursued both import substitution and export promotion simultaneously from the outset. The policy regime, referred to as the “export-import link,” pegged incentives directly to export earnings. Like most other countries at the time, Korea had a controlled fixed exchange rate that maintained an overvalued currency, as well as a rigid import control regime. Exporting firms were allowed to retain a portion of their foreign exchange earnings, which they could sell at a premium, or to import restricted consumer goods for sale in the domestic market. Another element was generous ‘wastage allowances” on imported raw materials. To illustrate, if garment exporters were allowed 15 per cent wastage on fabrics imported to make clothes for export, and the actual wastage was 5 per cent, this was the same as allowing them to sell 10 per cent of their products in the domestic market.

The effect of these incentives was to substantially offset the protection of the domestic market and to keep domestic-oriented producers on their toes. Other incentives included subsidised credit and discounted tariffs on utilities and railway transport, also pegged to export performance. As export manufacturing grew, the case for protecting the domestic market diminished, since Korean goods could compete both abroad and at home. The protection regime was progressively rolled back such that by the late 70s, South Korea was, by and large, an open economy.

Embarking on a protectionist industrial policy today raises a number of vexing issues. I will highlight three.

First, what is it in aid of? The stated objective is to increase the manufacturing share of GDP. I have heard a figure of 15 per cent of GDP by 2022 mentioned. The manufacturing share of GDP has actually been trending downwards lately—7.7 per cent in 2018, down from 10 per cent five years ago. How much can protecting domestic industry contribute? In 2018 we imported Sh.218 billion worth of finished consumer goods—excluding motor vehicles—accounting for 12 per cent of total imports, and 9 per cent of the value of domestic manufactured goods. If all these goods were to be manufactured locally, it would increase the manufacturing share of GDP from 7.7 to 8.5 per cent. But of course, whatever protectionist policies are envisaged will not constitute anywhere near total substitution and will at best have a negligible impact.

Tea, on the other hand, is a labour intensive crop. It needs to be picked and tended meticulously by hand throughout the year. Smallholder tea farmers work in their fields every day. The economic law of comparative advantage predicts that a country’s competitiveness will reflect its factor endowments, that is, capital-rich countries will be competitive in capital intensive goods, and labour-rich countries in labour intensive goods.

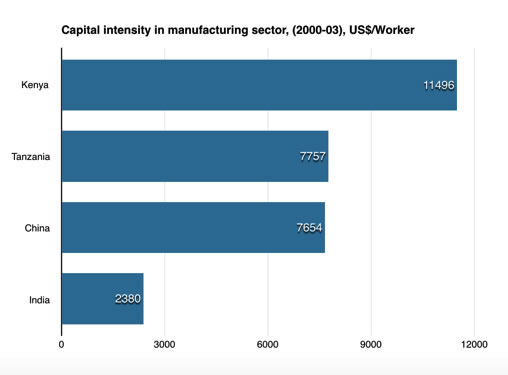

The most critical imperative that any industrial policy ought to address is jobs. We need millions of jobs. Kenya’s industry is capital intensive and not job-creating. A World Bank study from a decade ago showed that Kenya’s manufacturing sector was 50 per cent more capital intensive than China’s, and almost five times as capital intensive as India’s (see chart below). Although the data is old, the structure of the industry has not changed that much. This is of itself a legacy of an import substitution industrial policy which promoted the capital intensive goods that the country imported, as opposed to an export-oriented policy which would promote the industries that could utilise developing countries’ abundant labour.

Second, Kenya is a member of the East African Community (EAC), COMESA, and the new African Free Trade Area (AFTA) trading blocs, which agreements we have signed and ratified. Under the EAC in particular, Kenya is bound by a common external tariff (CET). Kenyan manufacturers are the biggest beneficiaries of these trading blocs. In 2018 Kenya exported goods worth Sh.90 billion ($1.9 billion) to EAC and COMESA, accounting for 30 per cent of total exports. We made imports of Sh.123 billion ($1.23 billion), thus running a surplus of Sh.67 billion ($670 million). Virtually all of Kenya’s exports to the region are manufactured goods. The country can ill afford to begin a trade war with the regional partners, who would only be too delighted to find reasons to lock Kenyan goods out of their markets. How is the government going to protect local industries without jeopardising regional integration?

Second, Kenya is a member of the East African Community (EAC), COMESA, and the new African Free Trade Area (AFTA) trading blocs, which agreements we have signed and ratified. Under the EAC in particular, Kenya is bound by a common external tariff (CET). Kenyan manufacturers are the biggest beneficiaries of these trading blocs. In 2018 Kenya exported goods worth Sh.90 billion ($1.9 billion) to EAC and COMESA, accounting for 30 per cent of total exports. We made imports of Sh.123 billion ($1.23 billion), thus running a surplus of Sh.67 billion ($670 million). Virtually all of Kenya’s exports to the region are manufactured goods. The country can ill afford to begin a trade war with the regional partners, who would only be too delighted to find reasons to lock Kenyan goods out of their markets. How is the government going to protect local industries without jeopardising regional integration?

Third, the case for protectionist import substitution regimes was predicated on the infant industry argument—protecting nascent industries until they were strong enough to compete. The problem arose because, like our sugar industry, and Pan Paper for that matter, there was no incentive to grow up, and the state lacked the political will to roll back the protection until economic crises compelled them. The industries that are now to be protected are not babies. What is the case for protecting grown-up industries, some of which are already dominant oligopolies in their sector? Until when will they be protected, and what new policy instruments are there to ensure that this protection regime will not go the route of the old one? Protecting mature incumbents translates to not just protection from competing imports, but also giving them more muscle to fight potential entrants into their markets. Essentially, it amounts to entrenching cartels, and Kenyatta’s statement—which makes reference to taking advantage, extortion and overpricing—demonstrates that Kenyatta is actually alive to this fact. Why is he contradicting himself? State capture.

–

Read Also