Sudan is on the brink, and not a day too soon. The independence of South Sudan a decade ago took with it 90 percent of total oil reserves. Even though Sudan got a good deal for the use of the pipeline including securing a compensation of $2.6 billion for future lost oil earnings, easily the biggest aid transfer from one African country to another, production disruptions in South Sudan have hit revenues hard. This shock was compounded by the effect of international sanctions and the Darfur insurgency. Sudan needed fundamental economic restructuring that it has not pursued, partly because it was also hamstrung by these two factors.

The independence of South Sudan a decade ago took with it 90 percent of total oil reserves. Even though Sudan got a good deal for the use of the pipeline, production disruptions in South Sudan have hit revenues hard.

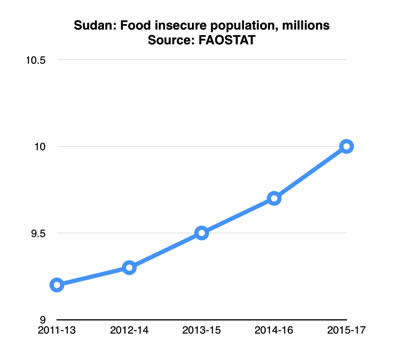

A severe hard currency shortage has taken its toll on the country’s production capacity. Shortages stoked inflation. The government compounded the problem by tightening monetary policy, starving the economy of credit. Nowhere is this more evident than in agriculture, plagued by lack of credit, fuel shortages and deterioration of the capital stock. Data published by the FAO show food insecurity rising sharply (see chart).

Late last year, President Omar el Bashir dissolved government and appointed a leaner one that he said would respond to the economic crisis—too little, too late. Inflation is now running at 70 percent. Demand management of supply shock inflation was never going to work. One of the new government’s first actions was to devalue the Sudanese Pound; it slid from 28 to 47 pounds to the dollar. A year and a half ago, it was exchanging at 6.7 pounds to the dollar. With an economy in meltdown, a hungry population, few friends and powerful foes, Khartoum has very limited options and nowhere to turn.

Late last year, President Omar el Bashir dissolved government and appointed a leaner one that he said would respond to the economic crisis—too little, too late. Inflation is now running at 70 percent. Demand management of supply shock inflation was never going to work. One of the new government’s first actions was to devalue the Sudanese Pound; it slid from 28 to 47 pounds to the dollar. A year and a half ago, it was exchanging at 6.7 pounds to the dollar. With an economy in meltdown, a hungry population, few friends and powerful foes, Khartoum has very limited options and nowhere to turn.

Sudan’s problems are patently political. In a nutshell, it is the failure to find a political formula to hold together a huge, culturally and geographically diverse country. For whatever reason, the ruling elite in Khartoum has pursued Islamist hegemony. This is what ultimately led to the break up with South Sudan.

Before its break up, Sudan was Africa’s biggest country at 2.5 million square kilometres. At 1.86m square kilometres it is still the third largest, behind Algeria (2.4m) and the DR Congo (2.34m). The old Sudan is about the size of the five biggest EU countries (France, Spain, Sweden, Norway Germany plus the UK), and if we start from the other end, Sudan would have fitted 36 of Europe’s 50 countries starting with the Vatican (0.44 sq. km) all the way to the UK (249,000 sq. km).

Sudan’s problems are patently political…the failure to find a political formula to hold together a huge, culturally and geographically diverse country.

Neighbouring Ethiopia is also experiencing political convulsions. Ethiopia is Africa’s second most populous country after Nigeria, with a population of 100 million people. Though never colonised, Ethiopia is a fractious nation that struggles to hold itself together, with secessionist movements in Ogaden and Oromia regions. Eritrea managed to break away. DR Congo, Africa’s second largest country now, has just held a very African presidential election two years late. The war that has raged there for the last two decades ranks as the most deadly conflict since the Second World War.

At the other end of the scale, and as this column has previously observed, Africa’s smallest countries are also its most successful. The Freedom House Index 2018 ranks ten African countries as fully free/democratic (Benin, Botswana, Cape Verde, Ghana, Mauritius, Namibia, Sao Tome & Principe, Senegal, South Africa, Tunisia) of which only one, South Africa is a big country. The average population of the ten countries is 13 million – 8 million when excluding South Afric – less than half the continental average of 21 million. Geographically, Botswana (pop. 2.3m) and Namibia (pop. 2.5m) are peculiar in that they are physically large countries with small populations. Excluding South Africa and these two, the average size of the other seven is 100,000 sq. km, against a continental average of 536,000 sq. km.

The old Sudan is about the size of the five biggest EU countries (France, Spain, Sweden, Norway Germany plus the UK), and if we start from the other end, Sudan would have fitted 36 of Europe’s 50 countries…

Countries rated as “partly free” average 354,000 sq. km and 26 million people. Those ranked “not free” average 800,000 sq. km. and 24 million people. Of eight countries that are over a million square kilometres (Algeria, DR Congo, Libya, Angola, Chad, Mauritania, Sudan, Niger) seven are ranked “not free”— Niger is the exception. There are five small countries ranked as unfree, i.e. less than 100,000 sq. km (Burundi, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Rwanda, Swaziland), six if you include Eritrea, which is just over the 100,000 sq. km threshold, out of a total of 22. Well governed African countries are almost invariably small, while badly governed ones are predominantly large.

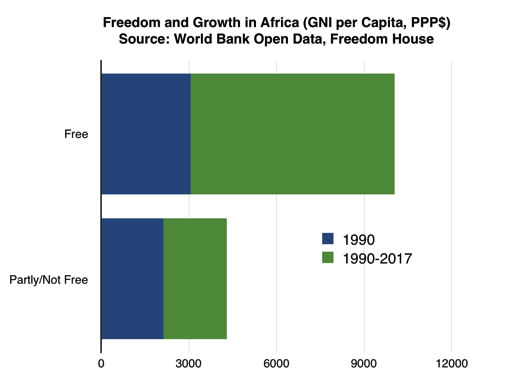

When it comes to governability, size does seem to matter. And as it turns out, governability has considerable economic payoffs. Africa’s “free” countries have increased income per person by three times more than the rest of the continent since 1990 (see chart).

When it comes to governability, size does seem to matter. And as it turns out, governability has considerable economic payoffs. Africa’s “free” countries have increased income per person by three times more than the rest of the continent since 1990 (see chart).

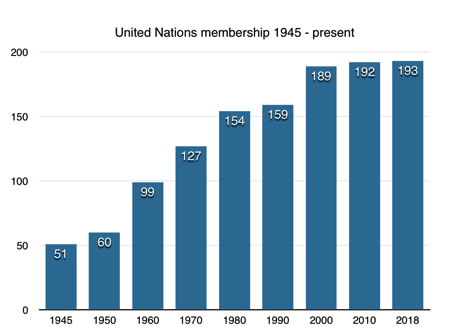

Nation-states like to project themselves as sacrosanct, immutable entities. Few political principles are proclaimed with as much fervour and fury as territorial integrity. It is an illusion. The United Nation membership of sovereign nation-states stands at 193, up from 51 founding members in 1945. The number of nations has increased 3.8 times, faster than the world population (2.9 times) Nation formation was at its height during decolonization (1950-80) growing from 60 to 154. (see chart). There was another surge after the collapse of the Soviet empire (1990 – 2000) when another 30 nations emerged. Since then only Eritrea and South Sudan have joined the ranks. But there is a pipeline of close to 70 dependent territories with nationhood potential and aspiration as well as pesky secessionist movements on every continent. Brexit could beget an independent Scotland.

Nation-states like to project themselves as sacrosanct, immutable entities. Few political principles are proclaimed with as much fervour and fury as territorial integrity.

In a 1995 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper On the Number and Size of Nations (expanded into a book The Size of Nations), political economists Alberto Alesina and Enrico Spolaore develop an economic model of nation formation. The core question they ask is: what is the optimal size of a nation, or put another way, how big should nations be?

They postulate that the essence of nations is the provision of a “public good” called government.

They postulate that the essence of nations is the provision of a “public good” called government.

Government is a fixed cost which is financed by taxing people. Fixed cost means that there are economies of scale—the larger the country the less the cost per citizen. But people are also diverse. Different communities will have different preferences. A community in a dryland will value water; a coastal fishing community, maritime security; a trading community roads throughout the territory, and so on. In this scheme of things, the calculus of nation building entails balancing the economies and diseconomies of scale.

Alesina and Spolaore consider two political orders by which nations could come about, namely democracy and autocracy.

In democratic nation building, communities would be free to choose. If they are unhappy in a particular nation, they can call a referendum. To illustrate, think of the world as consisting of 1000 communities of interest – let’s call them nationalities, ethnic groups if you like – with a population of 100,000 each. The cost of setting up government is a trillion shillings. Further still, government can only be at one location, let’s call it the centre, and the benefits of government are directly proportional to proximity to the centre. You can think of the centre as geographical or cultural distance, or both.

It stands to reason that people would be happiest if each nationality had its own government, but this would come with a price tag of Sh.10 million per citizen. It would also be immensely inefficient, as the total cost of government would be a thousand trillion shillings. Conversely, a world government would cost each citizen only Sh.10,000. As per our closeness to government assumption, the communities farthest from centre of the world government would be obliged to pay the same tax and receive very little benefits. They would be marginalized.

Let’s begin with a configuration: take 10 nations of 100 communities. Think of the political geography as a circle with governments located at intervals of 50 communities i.e. governments located in the middle of 100 communities. The communities closest to governments get 1.5 times what they put in. Benefits decline by 2 percent of the tax (so that community number 25 on the line gets exactly what it put in. Those farther along the line get progressively less until the 50th community, which gets only half what it put in.

If the neighbouring border communities would persuade the other “losers” to secede they end up being at the centre of a new circle of countries, resulting in double the countries with half the population. But this would mean paying double the tax, but because they are smaller countries there are fewer communities that are marginalized overall. We can surmise that under democratic order, this political calculus would continue until the benefits of proximity to government balance out with the higher tax per citizen.

The other political regime is autocracy, which Alesina and Spolaore call a Leviathan order a la Hobbes. In this order, the state is a protection racket, where residents of a territory agree to pay tribute to a warlord in exchange for protection from predation by other warlords, along the lines of Mancur Olson’s “roving” and “stationary” bandit model. A Leviathan has two objectives. First, to extract as much tribute as it can without triggering revolt and second, to expand territory – market share, if you like. Territory can be gained by conquest or offering neighbouring communities a better deal than the resident warlord.

It turns out that Leviathan’s problem is analogous to an oligopolistic industry (a market with a small number of players) As with oligopolistic markets, the first best solution is a cartel. The logic is as follows. War is expensive. So is predatory pricing whose most likely consequence is to trigger price wars which hurt every player. Leviathans would do best by sitting round a table and carving out territories amongst themselves. This logic seems to accord with the 1885 Berlin Africa conference and the Peace of Westphalia of 1648.

The Alesina-Spolaore model yields three propositions on nation formation:

First, neither the democratic order or autocracy achieves the ideal number of states. Democracy leads to too many small states and autocratic order leads to too few.

The second has to do with the impact of free trade. Consider the case when there is no trade between countries. Without trade it is economically advantageous to be a big country on account of a bigger market. This will add to the disadvantage of being a small country over and above the high overhead of governing itself. But with free trade, borders lose economic relevance. Small countries get to have their cake and eat it, like Switzerland, which trades freely with the EU, and has the highest average income in Europe despite not being a member of the EU. It should not surprise that it is Britain, long accustomed to having its cake and eating it, that finds itself in the Brexit predicament.

The third proposition is that decentralization can mitigate the fragmentation dynamic inherent in the democratic order. Decentralization mitigates the complexity of diversity. With decentralization, the centre provides those public goods where economies of scale are significant, while the local governments take care of those whose prioritising will vary widely across the different constituent parts.

…With free trade, borders lose economic relevance. Small countries get to have their cake and eat it, like Switzerland, which trades freely with the EU, and has the highest average income in Europe despite not being a member of the EU.

What to make of all this? Let’s do the math.

The modern nation state is a European invention. In this regard, Europe provides as good a benchmark of organic nation-formation as there is. The United States is a natural experiment of self-forming nations. The European countries average at 164,000 sq. km including Russia and 126,000 excluding Russia with average populations at 15m and 12 million respectively.

However, the typical European country is between 40,000 and 100,000 sq. km with populations between two and ten million people. American states are not that different, averaging 146,000 sq. km and 6.3 million people, with only three states with populations over 20 million (California, Texas and Florida).

The “natural” nation-state it seems is of the same order of magnitude as Africa’s small successful states. The governable African country would seem to be in the eSwatini (17.000 sq. km)- Ghana/Guinea (240,000 sq. km) ballpark.

How to hold onto and sustain plunder of such massive territories in the face of expanding political freedom, globalization, huge diverse populations and ecological pressure? Leviathans have their work cut out.

Africa. Average size of country: 607,000 sq. km including the Sahara desert, 423,400 excluding the Sahara desert—3.4 times and 2.6 times the European and US respectively—consistent with the handiwork of a plunder-maximizing Leviathan cartel. Average population currently is 24 million, but Africa’s population is projected to reach 2.5 billion in 2050, which works out to 50m per country.

How to hold onto and sustain plunder of such massive territories in the face of expanding political freedom, globalization, huge diverse populations and ecological pressure? Leviathans have their work cut out.