A few weeks ago the CS Treasury was kind enough to publish and gazette the government’s income and expenditure statement for July, the first month of the current financial year. They are only a few numbers, but they are quite revealing.

The government opened the year with KSh 102.8 billion in the bank. It raised KSh 99 billion from taxes, and borrowed KSh 30 billion locally, that is, total inflows of KSh 129 billion during the month. How was the money spent? Debt took KSh 68 billion, just under 70 percent of the tax raised. The counties and development budget got no money at all. The Treasury closed the month with KSh 110.7 billion, KSh 8 billion more than the opening balance. Why did the Treasury hoard money when the counties and development projects were starved of cash? I will come back to that question shortly.

The government opened the year with KSh 102.8 billion in the bank. It raised KSh 99 billion from taxes, and borrowed KSh 30 billion locally, that is, total inflows of KSh 129 billion during the month. How was the money spent? Debt took KSh 68 billion, just under 70 percent of the tax raised. The counties and development budget got no money at all. The Treasury closed the month with KSh 110.7 billion, KSh 8 billion more than the opening balance. Why did the Treasury hoard money when the counties and development projects were starved of cash? I will come back to that question shortly.

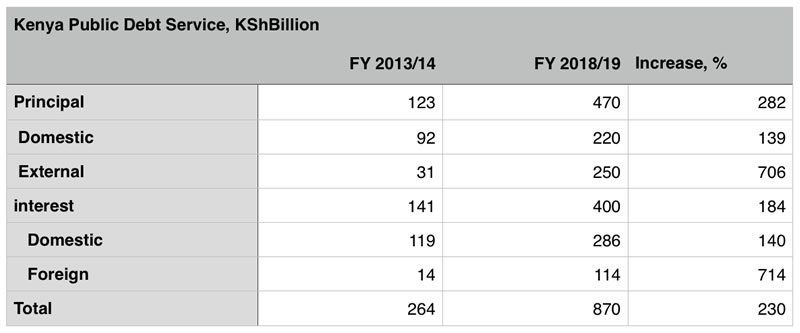

It is tempting to think that this was only the first month of the financial year, and things will look up. Not quite. Treasury puts revenue for the full financial year at KSh 1.34 trillion which translated to a KSh 112 billion monthly average, so the July revenue figure is low but not far off the mark. The debt service budget for the year is KSh 870 billion, which works out to KSh 72.5 billion per month so the July figure of KSh 68bn is also consistent. The domestic borrowing target for the year in the budget is KSh 270 billion, which works out to KSh 23 billion per month, so the July borrowing of KSh 30 billion is well above target.

In essence, the July statement is a good snapshot of the state of government finances. Unless revenue increases dramatically, the only way the government will be able to stay afloat is by excessive domestic borrowing. Borrowing more than it is doing already will put paid to any chances of recovery of credit to the private sector, which stalled three years go. And one does not have to be an economist or finance expert to appreciate that a person, business or government spending 70 percent of income to service debt is distressed.

How did we get here? Binge borrowing.

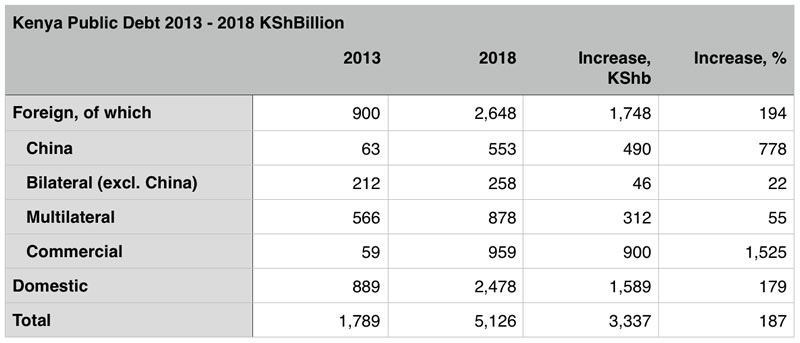

As at end of June 2018, our total public debt was KSh 5.2 trillion, up from KSh 1.8 trillion five years ago, an increase of KSh 3.3 trillion. Jubilee has borrowed close to double the debt it inherited. The debt has increased more or less equally between domestic and foreign borrowing. The second is cost of debt.

As at end of June 2018, our total public debt was KSh 5.2 trillion, up from KSh 1.8 trillion five years ago, an increase of KSh 3.3 trillion. Jubilee has borrowed close to double the debt it inherited. The debt has increased more or less equally between domestic and foreign borrowing. The second is cost of debt.

Unless revenue increases dramatically, the only way the government will be able to stay afloat is by excessive domestic borrowing. Borrowing more than it is doing already will put paid to any chances of recovery of credit to the private sector, which stalled three years go. And one does not have to be an economist or finance expert to appreciate that a person, business or government spending 70 percent of income to service debt is distressed.

The stock of debt has increased 187 percent but debt service outlays are up 230 percent, from KSh 264 billion to KSh 870 billion. The standout figure here is foreign interest, which has increased sevenfold from KSh 14 billion to KSh 114 billion. This in turn, is explained by two factors, foreign commercial and China debt. Five years ago, foreign commercial debt was inconsequential— we owed only one syndicated loan and that was an exception. We were not in the habit of taking on foreign commercial debt. Five years on, commercial debt is the single largest item on foreign debt accounting for 36 percent of it. We owed China KSh 63 billion accounting for seven percent of foreign debt. Debt to China is now up to KSh 550 billion accounting for close to 30 percent. Commercial debt and China combined account for 80 percent of the increase in foreign debt.

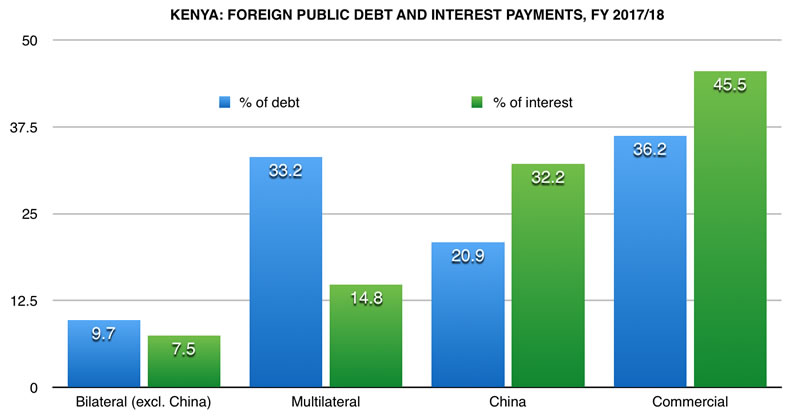

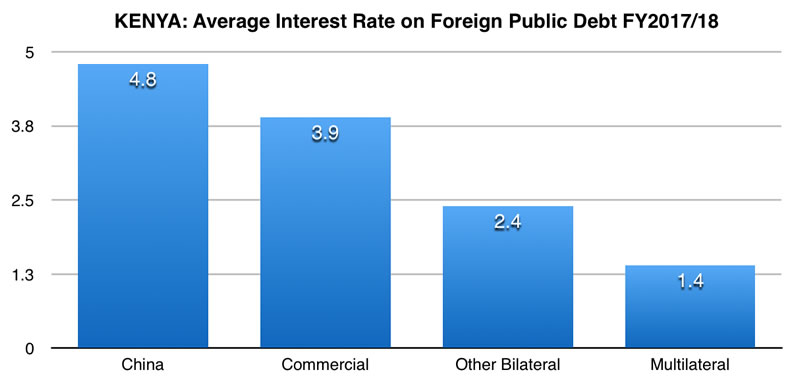

We, of course, expect commercial debt to be more expensive than the soft loans from bilateral and multilateral development institutions. But Chinese debt is not cheap either. Last year’s debt service figures show that we owed China 21 percent of foreign debt, but we paid them 32 percent of the interest. Multilateral lenders account for 33 percent of the debt but only 15 percent of the interest payments (See chart). The interest rates implied by these payments, although only a rough approximation, show that China’s debt is the most expensive at 4.8 percent, followed by commercial debt at 3.9 percent, other bilateral lenders at 2.4 percent and multilateral lenders are the cheapest at 1.4 percent. But as I said, these are implied rates, not the actual ones, as they do not reflect the debt movements within the year.

Jubilee has borrowed close to double the debt it inherited. The debt has increased more or less equally between domestic and foreign borrowing. The stock of debt has increased 187 percent but debt service outlays are up 230 percent, from KSh 264 billion to KSh 870 billion. The standout figure here is foreign interest, which has increased seven fold from KSh 14 billion to KSh 114 billion. This in turn, is explained by two factors, foreign commercial and China debt.

Different components of debt affect the budget differently. Interest comes out of the recurrent budget, and in effect from revenue. Working with a realistic figure of KSh 1.4 trillion revenue, the interest burden this year takes 29 percent of revenue up from 14 percent five years ago. In fact, interest cost is now equivalent to 90 percent of the wage bill as compared to 40 percent five years ago. Interest on debt is crowding out the Operations and Maintenance (O&M) budget. O&M is what makes government work. It is the money that enables the police to move around, and health facilities to treat patients, government laboratories to test food and drugs and so on.

On this trajectory, it will not take long for the recurrent budget to consist of only salaries and interest

The foreign debt consists of market debt (the Eurobonds), syndicated loans and term loans.

Eurobonds and syndicated loans are similar. The key difference is that syndicated loans are short-term notes, typically sold in two-year cycles, which banks typically hold to maturity. Amortization of bonds and syndicated loans (i.e. repayment of principal) is financed by new market debt, and is known as re-financing. The principal on bank debt has to be repaid. The key concern with market debt is the refinancing risk. The government has to be able to sell new bonds as old ones mature. The market conditions can change, or the investors risk-perceptions can change to the extent that the government is unable to sell enough bonds in which case it defaults. Alternately, it may have to offer such high returns that sooner or later, it cannot afford the interest, which amounts to the same thing— default.

Which brings me to the KSh102 billion shilling cash hoard— the money that government had but did not spend in July. This is half the money that the government raised in the second Eurobond six months ago. It was not spent because it was raised to refinance the maturing debt, KSh 250 billion this year. The balance has to be raised.

The key concern with market debt is the refinancing risk. The government has to be able to sell new bonds as old ones mature. The market conditions can change, or the investors risk-perceptions can change to the extent that the government is unable to sell enough bonds in which case it defaults. Alternately, it may have to offer such high returns that sooner or later, it cannot afford the interest, which amounts to the same thing— default.

The preferred option is to float another Eurobond, preferably a long dated one that does not come up for refinancing soon. The alternative is more syndicated loans which will cost more and come up for refinancing in two years. The market environment that they will be doing this is not favourable. When we raised the first Eurobond in 2014, the market was awash with “Quantitative Easing” (QE) money the US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank were “printing” in order to shore up their banking systems following the 2007 financial crisis, as well as “petrodollars” accumulated by oil exporters—recall that oil was selling at over $100 a barrel). The returns on financial assets in advanced markets were close to zero or negative.

Money managers were looking for higher returns wherever they could find them. Emerging markets were growing fast, and news out of Africa was dominated by the “Africa Rising” story.

Zambia was one of the first countries to jump onto the Eurobond bandwagon. Zambia floated a debut bond, looking to borrow US$500 million. It was heavily oversubscribed, attracting offers in excess of US$ 12 billion. Zambia accepted $750 million. Kenya’s stated objective was to issue a US$500 million “benchmarking” bond and use the proceeds to offset a syndicated loan that was due. How this turned to a US$ 2.8 billion is a story for another day— where it went is already the stuff of legend.

Our political class seems not to have understood the paradigm shift that becoming a sovereign borrower in international markets entails. Going to the market is analogous to a business going public. When a company is private, its affairs are dealt with behind closed doors. The only way unhappy investors can express their views is with their voices, or voting out directors during the annual general meetings, and this is usually quite difficult as typically, the insiders usually have more shares than outsiders. When a company gets listed on the stock exchange, investors don’t have to wait for AGMs. They communicate with the company every day by either buying or dumping the stock. Facebook’s share price fell 11 percent (US$134 billion) in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal—and that’s all the shareholders needed to say.

Prior to “listing” in the international sovereign bond market, our financial affairs were discussed behind closed doors between the government and its external financiers led by the IMF, and enforced through “conditionalities.” Sanctions for non-performance were flexible and negotiable, and influenced by political considerations. We call this programme discipline. After “listing”, the bond yields work the same way as share price, punishing or rewarding the country for good or bad economic management as the case maybe. We call this market discipline. The IMF continues to have a role, but a different one— providing a form of credit enhancement to the markets.

Our political class seems not to have understood the paradigm shift that becoming a sovereign borrower in international markets entails. Going to the market is analogous to a business going public. When a company is private, its affairs are dealt with behind closed doors…When a company gets listed on the stock exchange, investors don’t have to wait for AGMs. They communicate with the company every day by either buying or dumping the stock.

But Zambia’s government does not seem to have gotten that memo. Sometime ago it organized national prayers for the Kwacha, hardly a confidence building measure. A quarrelsome negotiation with the IMF broke down in February. Last week, the government kicked the IMF out of the country for “spreading negative talk”. The markets responded accordingly. Zambia’s bonds are trading at a bigger discount than Mozambique which has already defaulted.

As of last week, Zambia’s bonds were trading at a yield of 15 percent. An increase in the yield corresponds to a decline in value of a bond, and vice versa. Zambia’s debut Eurobond carries a coupon of 5.375%, and was issued at a yield at 5.625%, meaning that investors paid $93.50 for $100 of face value. A yield of 15 percent means that the bond is now trading at $36, a 60 percent fall in value. As summed up by an investor in Zambian Eurobonds: “It’s not a place that investors would rush into even if emerging markets become popular again. People will be cautious about Zambia until it produces better numbers or gets an IMF deal.”

Why our Treasury mandarins have been bending over backwards for a deal with the IMF is now readily apparent. IMF deal or no-deal, the government will have to produce better numbers. Healthy foreign exchange reserves are good, but reserves don’t service debt; revenues do. The markets want to see fiscal consolidation. The markets do not send missions. They dump your bonds.

The low-down: Mega projects are off the table, as is the “Big Four.” The SGR is not going past Naivasha anytime soon. The only order of business is crisis management – that is, if the government survives. Looking around, the odds are not good. The Greek crisis consumed five governments. Argentina went through five presidents in two weeks following imposition of the “corralito” (small enclosure) austerity measures in December 2001. The EPRDF autocracy in Ethiopia, erstwhile poster child of Africa’s new breed of authoritarian developmental regimes, did not run out of bullets or prisons. It ran out of money, and unravelled. Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Malaysia have ejected the mega-project mega-corruption governments that corralled them into China’s debt trap. Earlier this week Sudan’s President Omar al Bashir dissolved his government and appointed a new prime minister tasked to form a leaner government “as part of austerity measures to tackle economic difficulties.”

Mega projects are off the table, as is the “Big Four.” The SGR is not going past Naivasha anytime soon. The only order of business is crisis management – that is, if the government survives. Looking around, the odds are not good. The Greek crisis consumed five governments. Argentina went through five presidents in two weeks following the imposition of austerity measures in December 2001. The EPRDF autocracy in Ethiopia, erstwhile poster child of Africa’s new breed of authoritarian developmental regimes, did not run out of bullets or prisons. It ran out of money, and unravelled…It is fair to say that Mr. Kenyatta is now caught between the hammer of the markets, and the anvil of politics.

It is fair to say that Mr. Kenyatta is now caught between the hammer of the markets, and the anvil of politics. That comes with the territory.