In the middle of this month, a very Kenyan scandal erupted in our parliament. This followed a round of accusations regarding an investigation by the Trade, Industry and Cooperatives Committee of the House into the controversial importation of thousands of tonnes of raw sugar allegedly adulterated with heavy metals by individuals themselves allegedly associated with figures around the president, his family and other top officials. The committee produced a report into the scandal implicating a cross-section of senior officials only for the very same parliament to reject the document. It emerged that MPs had been bribed for sums as little as KSh 10,000 (US$100) for their votes. An investigation is supposedly now underway, ordered by the Speaker, Justin Muturi – in other words, there is an investigation of the scandal of the investigation of a scandal.

While there is general skepticism about these kinds of inquiries ever leading to any real censure of our politicians, the scandal about a scandal was illustrative of something more significant to me. In the months since the Kenyatta-Odinga ceasefire deal, the so-called handshake, Uhuru Kenyatta has been on an anti-corruption crusade that has seen senior officials hauled before court; lifestyle audits embarked upon; and illegally constructed buildings demolished. The administration plays its bells and whistles, and new words du jour – ‘riparian’ land is duly noted – are peddled to exhibit the regime’s utter sincerity in this latest anti-corruption onslaught. The logic here appears to be that Mr Kenyatta is trying to put the corruption genie back into the bottle, manage his own political succession and establish a real legacy all at the same time.

Attempting to do this all at once has meant the anti-corruption crusade is even more political than these things usually are in developing countries. Indeed, in terms of grand optics this latest escapade appears maxed out with the arrest of a ‘big fish’, Evans Kidero, the former governor of Nairobi, and the made-for-TV demolitions of illegally constructed buildings. In terms of Kenya’s political progression, the ultimate candidate for arrest vis-à-vis corruption would be Deputy President, William Ruto and his cohorts. ‘Stopping Bill’, as I have argued before is first and foremost a political project with anti-corruption accompaniments.

The politics of anti-corruption was on display last week with the publication of a curious survey by Ipsos Synovate that asked who Kenyans thought were the most corrupt living politicians. The ‘winners’ were the Deputy President William Ruto and Kirinyaga Governor, Anne Waiguru, the former cabinet secretary in the scandal-ridden ministry of devolution. Both of them immediately cried foul and protested that their political enemies were targeting them to undermine their political ambitions.

Indeed, one of Mr Kenyatta’s more breathtaking achievements has been to distance himself from his own deputy and presumptive successor without openly coming out and saying so. This has been particularly confusing to the President’s largely Kikuyu ethnic base that has spent the past five years defending the President and his deputy as a collective. Among the more notable epiphanies among Jubilee’s Mt Kenya supporters is their sudden discovery of how evil Mr. Ruto is; it was quite the opposite a year ago when he was steering Jubilee’s election campaign. Thus is Kenya’s cynical brand of politics though. Outside his core Kalenjin constituency, only the mainstream churches, to whom Mr. Ruto has become an important patron, have remained steadfast in his implicit defense. But I digress.

The politics of anti-corruption was on display last week with the publication of a curious survey by Ipsos Synovate that asked who Kenyans thought were the most corrupt living politicians. The ‘winners’ were the Deputy President William Ruto and Kirinyaga Governor, Anne Waiguru, the former cabinet secretary in the scandal-ridden ministry of devolution. Both of them immediately cried foul and protested that their political enemies were targeting them to undermine their political ambitions.

The scandal in parliament served as a reminder that all corruption investigations, especially when they are a political response to public outrage or external pressure, specifically target key governance institutions. People around President Moi corruptly extracted 10 percent of GDP from the economy in the run up to the 1992 elections and after. Goldenberg brought the economy to its knees. It forced the Moi regime in 1993 to cave in to the Bretton Woods-inspired SAP austerity programme. Inflation skyrocketed, interest rates went through the roof, millions of Kenyans were impoverished as the cost of living ground them down, but the new air of political freedom seemed to assuage some of the pain. Now we could complain without being immediately locked up.

As part of the deal with the West, and also as a strategy manage public outrage about Goldenberg, the most convoluted and ineffective investigations and prosecutions of any scandal in Kenyan history were launched. Figures like Kamlesh Pattni, the late Wilfred Koinange, a former Treasury Permanent Secretary among others were regularly hauled before the courts as part of the wider Goldenberg prosecutions. By 2002 when the KANU regime was removed from power there were so many Goldenberg-related cases before the courts that no single government official could count them. They were all halted when Kibaki took office, and a Commission of Inquiry established. Despite it handing over its report in 2006 there has never been real accountability for Goldenberg and the over US$1 billion that was raided from the coffers.

Among the more notable epiphanies among Jubilee’s Mt Kenya supporters is their sudden discovery of how evil Mr. Ruto is; it was quite the opposite a year ago when he was steering Jubilee’s election campaign. Thus is Kenya’s cynical brand of politics. Outside his core Kalenjin constituency, only the mainstream churches, to whom Mr. Ruto has become an important patron, have remained steadfast in his implicit defense.

What the Goldenberg scandal demonstrated most starkly was the impact of these mega scandals on governance institutions, perpetrated by the same elite purporting to investigate them. No other scandal had damaged the credibility and public image of the judiciary more severely than Goldenberg. It was clear early on that huge sums of money flooded court corridors and totally paralysed that institution’s capacity to be even remotely effective in regard to land grabbing and general corruption matters. A slow and painful recovery process followed this shredding of the Judiciary. As part of this, a Judicial Service Commission was established in 2010 after the August promulgation of the new constitution to vet judges and revive the independence of the judiciary.

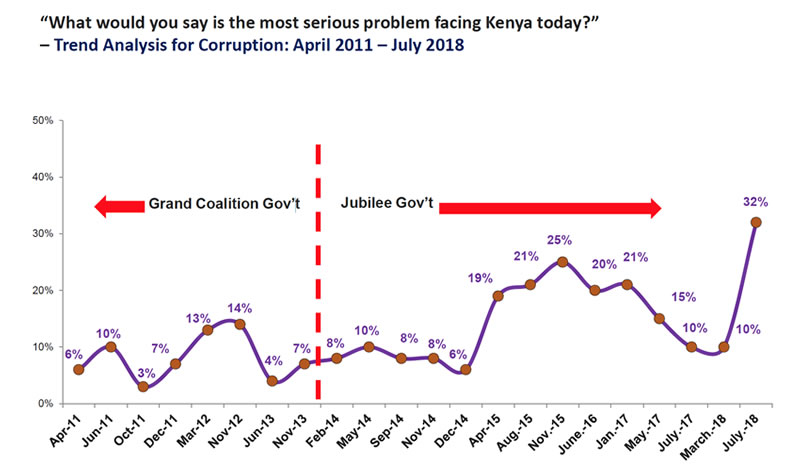

Source: Ipsos Kenya SPEC Barometer 2nd QTR 2018

Source: Ipsos Kenya SPEC Barometer 2nd QTR 2018

The scandal-within-a-scandal regarding the dodgy sugar imports earlier this year can be seen in this light. This time around, it is the Legislature that is being targeted. Last week the Public Service Commission explained that it had halted the process of civil servants declaring their wealth citing the need for further clarification on process issues

Over the past few weeks, the greatest excitement in the anti-corruption fight was generated by the demolitions of properties illegally constructed on road reserves and riparian land. Over the past five years, about US$4 billion stolen from the economy has been laundered mostly through a real estate boom that has transformed Nairobi’s skyline and cities and towns across the country. The chilling effect and blow-back from this particular dimension of the anti-corruption campaign is difficult to exaggerate. Typically, millions of corrupt dollars is deployed as hush-money into parliament, the judiciary, investigating agencies, civil service and the media. A deliberate leak of a telephone conversation and between the governors of Nairobi, Mike Mbuvi Sonko, and Kiambu, Ferdinand Waititu, revealed what most of us have suspected – that the anti-corruption fight is politically choreographed. This calls into question its sincerity. It also tells us that the corruption of our governance bodies will likely be accelerated precisely to cover its tracks. Scandals within scandals.

The scandal in parliament served as a reminder that all corruption investigations, especially when they are a political response to public outrage or external pressure, specifically target key governance institutions.

****

I continue to be persuaded that the current fight against corruption is also aimed at rebooting Mr. Kenyatta’s legacy and that of his family in the light of the fiscal bind his regime finds itself in following five years of unprecedented profligacy and theft. The government is preparing to introduce a 16 percent across-the-board VAT tax on petroleum products in addition to levies already introduced that have raised the cost of living for ordinary Kenyans. It is clear that the Jubilee regime is in the middle of what can only be described as an IMF structural adjustment programme, Version 2.0.

A deliberate leak of a telephone conversation between the governors of Nairobi, Mike Mbuvi Sonko, and Kiambu, Ferdinand Waititu, revealed what most of us have suspected – that the anti-corruption fight is politically choreographed. This calls into question its sincerity. It also tells us that the corruption of our governance bodies will likely be accelerated precisely to cover its tracks. Scandals within scandals.

In truth though, this isn’t an IMF programme of the familiar variety from the 1980s and 1990s. Our own greed and incompetence has led us to this point. Indeed, the IMF and World Bank have been accommodating to the point of complicity over the past five years, looking the other way as Kenya’s foreign debt increased by two and a half times from US$9 billion to US$25 billion. As David Ndii argues, the Chinese debt-financed SGR alone accounts for 30 percent of this increase; another 30 percent is by sovereign bonds for which the country has nothing to show. Public debt now stands at KSh 860 billion (US$ 8.6 billion), a staggering 72 percent of the last financial year’s tax receipts.

I continue to be persuaded that the current fight against corruption is also aimed at rebooting Mr. Kenyatta’s legacy and that of his family in the light of the fiscal bind his regime finds itself in following five years of unprecedented profligacy and theft.

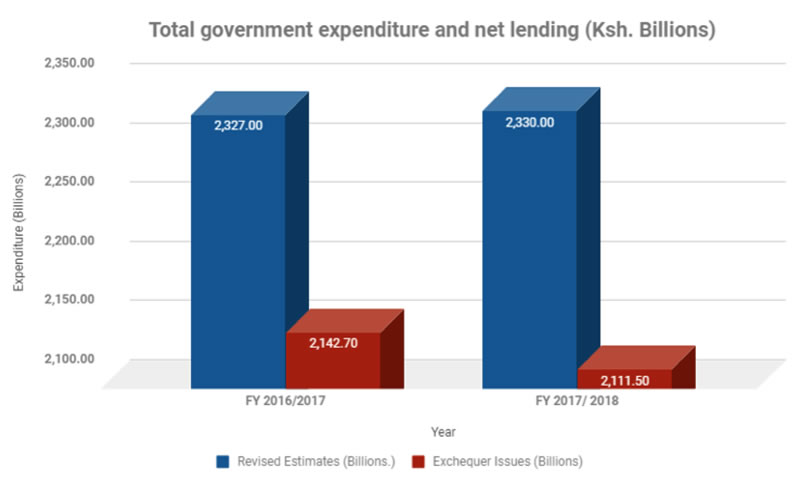

Facing insolvency the government has implemented a range of measures including the president halting all new project spending. Last week, the Council of Governors complained that in July the Treasury disbursed nothing to the Counties.

Sources: The National Treasury and Central Bank of Kenya

Sources: The National Treasury and Central Bank of Kenya

The IMF and World Bank have been accommodating to the point of complicity over the past five years, looking the other way as Kenya’s foreign debt increased by two and a half times from US$9 billion to US$25 billion.

It is on this economic front that the real challenge for Kenya over the coming months lies. It will quickly become a political one as well. Bulldozers knocking down temples are mere distractions in light of this.

Research by Juliet A. Atellah

Related Links

– The effects of 16 percent VAT on petroleum products

– Crucial: IMF team flies into Nairobi as State tightens spending

– Mt Kenya matatus announce 20pc fare increase

– Petrol price to hit Sh130 as VAT charge kicks in

– Leaked phone call between Waititu and Sonko reveals impunity