When Uhuru Kenyatta and his former rival, Raila Odinga, announced the “Building Bridges” initiative (ostensibly to promote peace and harmony in the country) following their famous touchy-feely handshake on the 9th of March, many people in Kenya’s coast region wondered when a bridge would be built at Likoni to ferry passengers to and from the mainland to Mombasa Island. Various suggestions appeared on Twitter, from retractable bridges of the type that are found on the Thames in London, to sky-high bridges that would allow ships to cross the Likoni Channel without hindrance. These suggestions, some of which were no doubt expressed by those who know a thing or two about how bridges are built, will most likely be ignored by the powers that be.

For years residents of Mombasa have wondered why the government has not built a bridge at a place that is crying out for such infrastructure. How long will local residents and tourists continue to rely on ferries to carry passengers and vehicles across the Likoni Channel? Are ferry cartels hindering the building of such a bridge? Who has the most to lose if such a bridge is built?

Conspiracy theories abound. Some say that powerful cartels have a monopoly on ferry purchases from abroad and so do not want to lose out on lucrative deals if more people start using the bridge rather than the ferry. Others speculate that the owners of certain airlines that have made a fortune from flying passengers from Nairobi to Ukunda’s pristine beaches in Diani will have the most to lose from a bridge at Likoni as tourists would be tempted to fly instead to Mombasa on a competitor’s airline and then take the road/bridge to Ukunda.

For years residents of Mombasa have wondered why the government has not built a bridge at a place that is crying out for such infrastructure…Conspiracy theories abound…powerful cartels have a monopoly on ferry purchases from abroad and so do not want to lose out on lucrative deals…Others speculate that the owners of certain airlines that have made a fortune from flying passengers from Nairobi to Ukunda’s pristine beaches in Diani will have the most to lose…

These theories might be true but it is equally true that our short-sighted policy makers have been unable to see the link between building actual bridges and prosperity. Bridges have linked people and made trade possible between different states and communities for centuries. Cities around the world have prospered and grown around bridges. Would Kolkata be a different kind of city without its landmark Howrah Bridge (now known as the Rabindra Setu Bridge)? And would Istanbul be the vibrant, cosmopolitan city it is today if the imposing Bosphorus Bridge linking Turkey’s Asia side to Europe had not been built? In some cases, bridges have become major tourist attractions. Imagine Paris without its delightful bridges across the Seine, London without the Tower Bridge or New York without the picturesque Brooklyn Bridge.

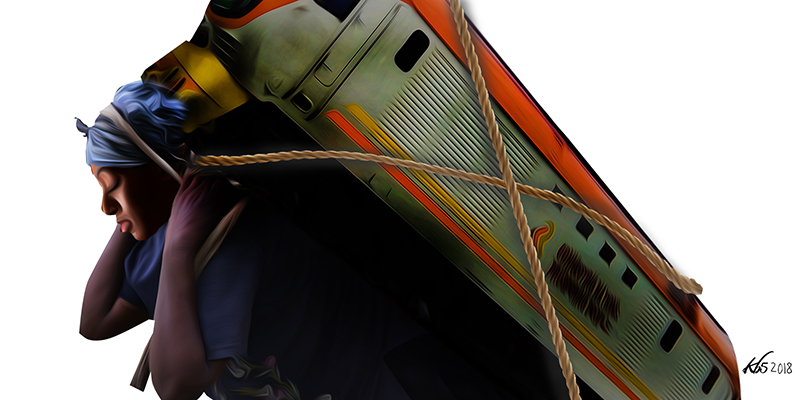

Death of a railway

As Kenyans marked the first anniversary of the controversial Standard Gauge Railway (SGR), dubbed the Madaraka Express – hailed as a success story by the Jubilee government despite the billions of shillings Kenyans now owe the Chinese who built it, and which may take decades to repay – another conversation regarding transport infrastructure emerged on Twitter. On one of those nights when you randomly wonder about the state of your nation, and worry about things like inflated electricity bills and why the price of Supaloaf bread has jumped so quickly from 27 shillings to 50 shillings, I asked my Twitter followers to imagine what it would be like to have a railway line that links Lamu to Malindi in the North coast, Mombasa and Kwale on the South coast. This tweet was prompted by a wedding invitation to Diani that I had declined because I don’t like driving on the Malindi-Mombasa highway and also because the prospect of catching the ferry from Mombasa to Likoni always fills me with dread.

The reaction was massive and instantaneous. Dozens of Twitter followers said that such a railway line would not only attract tourists but would also be a huge boost to the local economy as trade between different parts of the Coast increases and as more settlements emerge along the railway line, just as they did when the Uganda Railway was built more than a century ago. Some said that the Lamu-Kwale rail corridor would make coastal people more accessible to each other and would therefore help in “building bridges” between different communities.

The story of the decline of the Uganda Railway (later renamed variously as the Kenya and Uganda Railway, the East African Railways, the Kenya Railways and eventually Rift Valley Railways) is itself one of myopia on the part of policy makers. When the East African Community split in 1977, making East African Railways defunct, Kenya Railways became a fairly efficient parastatal that was tasked with running the country’s rail network. Up until the early 1990s, the parastatal ran a relatively reliable (but slow) daily passenger rail service from Nairobi to Mombasa and back. I remember the days when a night train journey on Kenya Railways was a romantic affair, complete with white linen bedding and silver cutlery.

However, by the mid-90s, the sleeping and dining experiences on this train had deteriorated considerably, but it was not as if it they could not be salvaged. The Mwai Kibaki administration made the mistake of first giving a concession for the management of the railway to a South African-led consortium, which killed what remained of the century-old railway, and later charging an Egyptian consortium with the impossible task of resurrecting it. In-fighting and complaints about the South African consortium’s lack of investment in the railway eventually led to the premature termination of the 25-year concession. Meanwhile, another Kibaki-initiated flagship transport corridor, the Lamu Port and South Sudan Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET), has yet to take off.

The railway suffered another major blow after the Kibaki administration exited in 2013. Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee administration did not care to revive the dying railway and instead opted for the expensive SGR option funded by Chinese loans, even though a World Bank study had estimated that the upgrading and refurbishment of the existing railway line would have cost less than one-fifth of what the SGR was going to cost the Kenyan taxpayer. In addition, the upgrading of the existing railway could have been funded by levies from the cargo itself rather than through huge borrowing from foreign banks. Besides, if the country was going to borrow money to build a railway, could it not have borrowed it for building a new network in areas where there are no train services?

Interestingly, the government has also contracted a US construction company, Bechtel, to build an expressway from Nairobi to Mombasa, which will in essence undermine and negate the original reason given for building the SGR – to move larger amounts of cargo faster. As the economist David Ndii has pointed out, the combined national debt arising from the SGR and the new expressway is a whopping $6 billion, or about a third of the country’s total foreign debt. How long will it take Kenyans to repay this?

One also wonders why the existing rail network, which is of immense historical and sentimental value, was abandoned in favour of a completely new one. Countless books have been written about the “Lunatic Express” and the toll it took on those who built it. Stories of heroic British engineers, man-eating lions and resilient Indian coolies have been captured in several books and films.

Interestingly, the government has also contracted a US construction company, Bechtel, to build an expressway from Nairobi to Mombasa, which will in essence undermine and negate the original reason given for building the SGR – to move larger amounts of cargo faster.

The history of British colonialism and Indian settlement in Kenya would be quite different if the railway had not been built. In fact, Nairobi would not exist today if railway engineers had not stopped at what was then known as Mile 327 to contemplate the daunting task of ascending the Kikuyu Escarpment into the Rift Valley. Nairobi owes its existence to the railway line that completely transformed urbanisation patterns in Kenya and opened up the country for European settlement – and eventual colonisation.

Although initially intended as a colonial vehicle for the exploitation and export of the country’s raw materials, the railway eventually developed its own ecosystem sustained by an army of engine drivers, station masters, ticket agents, vendors, baggage and cargo handlers, cooks, stewards and passengers. A job in the railways was considered stable and prestigious as it came with other perks, like housing. (Kenyan lawyer Pheroze Nowrojee, whose grandfather worked as an engine driver on the Uganda Railway from 1903 till 1933, writes nostalgically about that era in his book, A Kenyan Journey.) Sadly, the railway staff quarters in Nairobi, like the railway itself, have been allowed to deteriorate or to become the victim of land grabs.

Things are different in India. The Indian government did not neglect the vast railway network that it inherited from the British. On the contrary, it strengthened and expanded it. India’s rail network, which reaches almost all parts of this huge country, is the fourth-largest rail network (half of it is electrified) in the world, covering some 121,407 kilometres. Indian Railways, which is managed by an entire government ministry – the Ministry of Railways – employs some 1.3 million people and generated $29 billion in revenues last year. It is considered by most Indians as the most reliable and affordable means of transport and is used by rich and poor alike.

Trains have a democratising influence on society. On roads it is easy to distinguish rich users from the less well-off ones, the former in their luxury cars and the latter in crowded buses and matatus. But travelling by rail is different. On the London Underground, which covers 270 stations across the city and its suburbs, it is not unusual to find the Mayor of London seated next to ordinary working class Londoners.

India’s rail network, which reaches almost all parts of this huge country, is the fourth-largest rail network in the world – half of it is electrified – covering some 121,407 kilometres. Indian Railways, which is managed by an entire government ministry – the Ministry of Railways – employs some 1.3 million people and generated $29 billion in revenues last year.

There is also something about being able to use a mode of transport that allows you to get up and stretch your legs or to read a book in comfort. Trains, especially of the electric kind, are also among the most environmentally sustainable forms of transport.

The questions that much of the country’s population that is not served by a railway line are asking are: what has prevented Kenya from expanding its rail network across the country? Why are the benefits of trains only viewed through the prism of cargo from the port of Mombasa and not passengers across the country? How long will it take before there is a rail service from Garissa to Isiolo or from Kisumu to Kakamega? Or how about one from Machakos to Thika? Or a light-rail service within the city of Nairobi itself that would ease road traffic? It may not happen in my lifetime, but imagine the possibilities if these scenarios were to become reality.

What has prevented Kenya from expanding its rail network across the country? Why are the benefits of trains only viewed through the prism of cargo from the port of Mombasa and not passengers across the country? How long will it take before there is a rail service from Garissa to Isiolo or from Kisumu to Kakamega? Or how about one from Machakos to Thika? Or a light-rail service within the city of Nairobi itself that would ease road traffic?

These are the kinds of bridges we need to build, not the hollow kind promised by Uhuru and Raila, which are premised on the lie that a handshake will end uneven development in the country.