Western powers slowly tied a noose round their own necks by first installing Uganda’s National Resistance Movement regime, and then supporting it uncritically as it embarked on its adventures in militarism, plunder and human rights violations inside and outside Uganda’s borders.

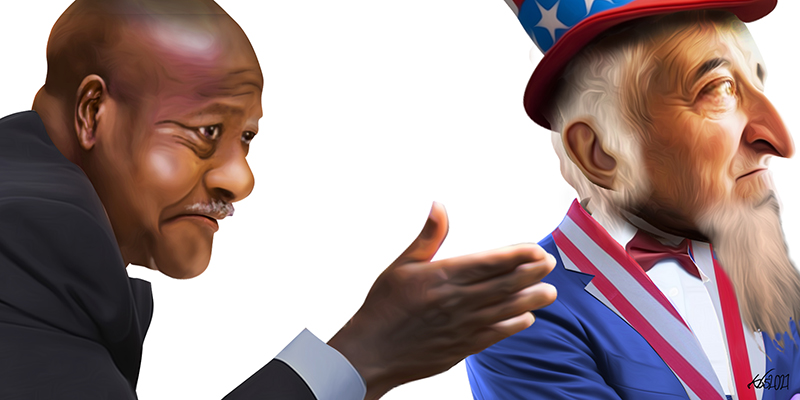

They are now faced with a common boss problem: what to do with an employee of very long standing (possibly even inherited from a predecessor) who may now know more about his department than the new bosses, and who now carries so many of the company’s secrets that summary dismissal would be a risky undertaking?

The elections taking place in Uganda this week have brought that dilemma into sharp relief.

An initial response would be to simply allow this sometimes rude employee to carry on. The problem is time. In both directions. The employee is very old, and those he seeks to manage are very young, and also very poor and very aspirational because of being very young. And also therefore very angry.

Having a president who looks and speaks like them, and whose own personal life journey symbolises their own ambitions, would go a very long way to placating them. This, if for no other reason, is why the West must seriously consider finding a way to induce the good and faithful servant to give way. Nobody lives forever. And so replacement is inevitable one way or another.

But this is clearly not a unified position. The United Kingdom, whose intelligence services were at the forefront of installing the National Resistance Movement/Army (NRM/A) in power nearly forty years ago, remains quietly determined to stand by President Yoweri Museveni’s side.

On the other hand, opinion in America’s corridors of power seems divided. With standing operations in Somalia, and a history of western-friendly interventions in Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, and even Kenya, the Ugandan military is perceived as a huge (and cut-price) asset to the West’s regional security concerns.

The DRC, in particular, with its increasing significance as the source of much of the raw materials that will form the basis of the coming electric engine revolution, has been held firmly in the orbit of Western corporations through the exertions of the regime oligarchs controlling Uganda’s security establishment. To this, one may add the growing global agribusiness revolution in which the fertile lands of the Great Lakes Region are targeted for clearing and exploitation, and for which the regime offers facilitation.

Such human resource is hard to replace and therefore not casually disposed of.

These critical resource questions are backstopped by unjust politics themselves held in place by military means. The entire project therefore hinges ultimately on who has the means to physically enforce their exploitation. In our case, those military means have been personalised to one individual and a small circle of co-conspirators, often related by blood and ethnicity.

However, time presses. Apart from the ageing autocrat at the centre, there is also a time bomb in the form of an impoverished and anxious population of unskilled, under-employed (if at all) and propertyless young people. Change beckons for all sides, whether planned for or not.

This is why this coming election is significant. If there is to be managed change, it will never find a more opportune moment. Even if President Museveni is once again declared winner, there will still remain enough political momentum and pressure that could be harnessed by his one-time Western friends to cause him to look for the exit. It boils down to whether the American security establishment could be made to believe that the things that made President Museveni valuable to them, are transferable elsewhere into the Uganda security establishment. In short, that his sub-imperial footprint can be divorced from his person and entrusted, if not to someone like candidate Robert Kyagulanyi, then at least to security types already embedded within the state structure working under a new, youthful president.

Three possible outcomes then: Kyagulanyi carrying the vote and being declared the winner; Kyagulanyi carrying the vote but President Museveni being declared the winner; or failure to have a winner declared. In all cases, there will be trouble. In the first, a Trump-like resistance from the incumbent. In the second and the third, the usual mass disturbances that have followed each announcement of the winner of the presidential election since the 1990s.

Once the Ugandan political crisis — a story going back to the 1960s — is reduced to a security or “law and order” problem, the West usually sides with whichever force can quickest restore the order they (not we) need.

And this is how the NRM tail seeks to still wag the Western dog: the run-up to voting day has been characterised by heavy emphasis on the risk of alleged “hooligans” out to cause mayhem (“burning down the city” being a popular bogeyman). The NRM’s post-election challenge will be to quickly strip the crisis of all political considerations and make it a discussion about security.

But it would be strategically very risky to try to get Uganda’s current young electorate — and the even younger citizens in general — to accept that whatever social and economic conditions they have lived through in the last few decades (which for most means all of their lives given how young they are) are going to remain in place for even just the next five years. They will not buy into the promises they have seen broken in the past. Their numbers, their living conditions, their economic prospects and their very youth would then point to a situation of permanent unrest.

However, it can be safely assumed that the NRM regime will, to paraphrase US President Donald Trump, not accept any election result that does not declare it the winner.

Leave things as they are and deal with the inevitable degeneration of politics beyond its current state, or enforce a switch now under the cover of an election, or attempt to enforce a switch in the aftermath of the election by harnessing the inevitable discontent.

Those are the boss’ options.

In the meantime, there is food to be grown and work to be done.