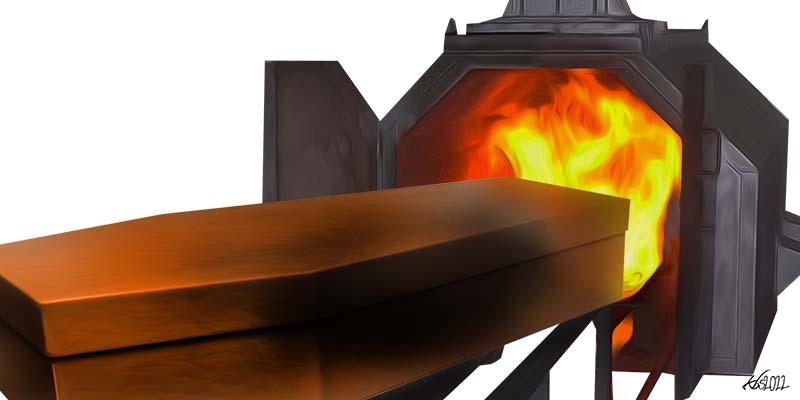

Every time a prominent Kenyan Christian is cremated instead of being buried, a debate ensues among Kenyan Christians on the best way of disposing of their dead. However, the real contestation is about whether Christianity sanctions cremation.

The attitudes of Christians have not shifted to favour cremation, despite the reforms the churches have made to their funeral policies. For instance, the Anglican Church of Kenya (ACK) adopted changes to accept cremations as a way of disposing of the dead in 1999. But when the ACK’s second Archbishop, Manasses Kuria, cremated the body of his wife Mrs Mary Nyambura Kuria in 2002, astonished Christians disapproved of his action.

It is noteworthy that Anglicans followed the lead of the Roman Catholic Church which relaxed its position on cremation following Vatican II. Prior to Vatican II, however, the Catholic Church had always justified the cremation of her dead in extraordinary circumstances, argues John F. McDonald. The Catholic Church allowed cremation in emergency cases where the quick disposal of bodies was a civil necessity, thus justifying the disposing of corpses by cremation for the public good in wartime, or during a serious epidemic.

To explore the debate, I have divided this paper in four parts. The first explains the historical development of burial as the Church’s core practice that Christians in Kenya have adopted. Further, it highlights various African customary norms on disposing of the dead. In the second part, the study mentions instances of cremation and explains why Christians are taking up the practice. The third part sets out a critical correlation of the findings with the normative traditions of Kenyan Christians. The fourth past applies the empirical data and theological discourse to offer a theory for action and, thus, revise the present praxis.

Theological tradition

Burial remains the core method of disposing of the dead among Kenyan Christians, although more and more of them are adopting cremation as an alternative. Here we explore the historical development of burial in Christianity and the various African customary norms on disposing of the dead.

Upon death, people perform particular rituals on the body before disposing of the corpse, rituals that Vyonna Bondi identifies as the most “primitive sign of religious faith is the ritualized burial of the dead”. These rites shadow a people’s gained spiritual traditions, since they understand death as a transition to the afterlife. This is a common thread linking ancient civilizations with the modern, the belief in the afterlife, which forms a fundamental feature of religious faith. Disposal of the dead is, therefore, a fulcrum balancing the living and the afterlife.

Burial is not inherently Christian. The Church acquired the burial custom from Judaism and the pagan communities. Margaret R. Bunson dates the Egyptians’ burial rites around c 6000- c 3150 BCE in the Pre-Dynastic Period, long before Judaism and Christianity. The most popular Egyptian practice of disposing of the dead was mummification, which was practiced as early as 3500 BCE, a practice that preserved the corpse buried in the arid sand. In his writings, Joshua J. Mark refers to “Ginger”, the preserved body found in a tomb in Gebelein, Egypt, and dated to 3400 BCE. Egyptian tombs were graves dug into the earth, the eternal resting place of the body (Khat), which they protected from grave robbers and the elements. These tombs became important in Egyptian civilization, as they used mud brick to build more ornate graves, the rectangular mastabas. It was from the mastabas that they developed the “step pyramids” and later the “true pyramids”.

The Egyptian burial rites were dramatic. Egyptians hoped that in mourning them, their dead would find bliss in an eternal land beyond the grave. According to Herodotus,

As regards mourning and funerals, when a distinguished man dies, all the women of the household plaster their heads and faces with mud leaving the body indoors, perambulate the town with the dead man’s relatives, their dresses fastened with a girdle, and beat their bared breasts. The men, too, for their part, follow the same procedure, wearing a girdle and beating themselves like the women. The ceremony is over when they take the body to be mummified.

The physical body was of immense importance to the Egyptians, which Mark illustrates using the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony. This ceremony was conducted to reanimate the corpse for continued use by the soul. They performed it by placing the mummy in the tomb, where a priest recited spells and touched the mouth of the corpse, to eat and drink, and the arms and the legs to move about in the tomb. So, to release the corpse on its journey to the afterlife, the people invoked more spells and recited prayers, such as The Litany of Osiris. Proper burial rituals were therefore very important and strictly observed. Even if one had lived an exemplary life, one would not reach paradise if one’s burial did not adhere to all their funerary rites.

Other civilizations and religions of the ancient world gained this belief through cultural transmission through trade on the Silk Road. Evidence of burial rites and customs of the Church in the early centuries is scanty for there were no known distinct Christian burial forums during the first two Christian centuries. The early Christians observed local burial customs, which R.A. Peterson affirms; there were no Christian burial customs. According to L.M. White, only in the late second century did the first unique Christian concerns regarding burial emerge even though the burial of the Christian dead was clear. In Geoffrey Rowell’s view, the rites of burial in early Christianity were not controversial matters and so did not feature in apologetic or polemical works. Hence, references to them are only incidental, which explains the dearth of information detailing Christian burial practices. During the Church’s first three centuries, cemeteries exhibited Christian care of their dead. To this day, the secret burial places—not the public cemeteries but the Roman catacombs—bear witness to the practice of burying their dead.

Even if one had lived an exemplary life, one would not reach paradise if one’s burial did not adhere to all their funerary rites.

Initially, Christians and pagans buried their dead in the same cemeteries. After the fourth century, Christians distinguished their graves, marking them with decorative representations and inscriptions. Besides, the graves differed in burial motif as well. Christians did not remember their dead with sadness and resignation; their dead preceded them to the shepherd’s paradise, “to the place of refreshment, light and peace”.

The first Christians upheld the Jewish burial customs, which they modified to show both local practices and Christian hope. They not only adapted contemporary non-Christian funeral practices but modelled them to show monotheism. This, notes J.W. Childers, defined Christian belief in the resurrection of the dead. Of all their influence in the Roman Empire, Julian ranks the care for their dead in burial as top in converting the empire. Christians expressed the characteristics of their new faith—their belief in the body’s resurrection—through reverence for the body in their funeral rites, thus giving us a long-established liturgy of Christian burial rites, comprising the funeral mass followed by the absolution over the body, and later burial in a consecrated or blessed grave. Thomas G. Long described this practice thus:

They invited once more the community of faith, and in dramatic fashion, to recognize that Christian life is shaped in the pattern of Christ’s own life and death. We have been, as Paul says in Romans, baptized into Jesus’ death and baptized into Jesus’ life: do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore, we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the father, so we too might walk in newness of life. (Rom. 6:3–5)

Kenya’s Anglican Church shares other Christian denominations’ understanding of burial as a pious tradition among Christians, a practice which John F. MacDonald notes, “The church has always tried to encourage by supporting it with an appropriate ritual designated to highlight the symbolism and religious significance of burial.”

However, every occurrence of death confronts African Christians with the heightened tension between the Christian tenets and their African worldview of disposing corpses. They express this in the belief that the dead have power over the living. In most African societies, life and death exist together on a continuum as they understand the concept of death in tandem with life, with death as a rite of passage through which one becomes an “ancestor” and continues to live in the community. Prof. A.B.C. Ocholla-Ayayo claims that “death amongst the Luo is expressed as a ‘crisis of life’ and an element in the life cycle of the individual”. Death and funeral rites amongst the Luo and the Luhya involve not only the bereaved immediate family but also include other relatives and the community at large. Thus, the exit at death only means entering the invisible world. Hence, proper death rites became a necessity as a guarantee of protection for the living.

The manner and location of the burial among the Luo is determined by the individual’s status in society, the nature of their death, their deeds, as well as the rituals performed to appease the ancestors. The arraying of the deceased’s body remains an important part of Luo custom. After observing burial rites, the body is buried in a rectangular grave about five feet or deeper. The Luo, like the Luhya and the Gusii, bury their dead within the deceased’s homestead. They also bury their dead infants (including the stillborn), although Luhya methods differ from those of the Luo in insignificant details. The differentiation in burial methods, asserts Ocholla-Ayayo, highlights the differing social distinctions amongst the members of the tribes, thus maintaining the societal order.

The rituals surrounding death amongst Africans are systematic. They keep ancestral links, guide succession and inheritance, and underscore the interdependence and the conjoint relations of living kin. The Luo observed these rites to prepare for the afterlife, which was part of the continuum that fulfils one’s social responsibilities. It evinced the intricate relationship between the dead and the living in Luo nomenclature, which incorporates the name of the spirits (nying juogi). For the Luhya on the other hand, funerals were intrinsically a custom aimed at pleasing the ancestral spirits, a notion that is strengthened by the observance of Lisaabo, the remembrance of dead ancestors. Hence, the ritualistic slaughter of animals and the serving of food and drinks to mourners during funerals.

Every occurrence of death confronts African Christians with the heightened tension between the Christian tenets and their African worldview of disposing corpses.

Nomadic communities, such as the Maasai, did not allow the sick or aged to die in the home. Instead, they took them into the forest, to a hillside, or abandoned them by a river. Once dead, they buried them under a tree in the sitting position with the deceased’s chin resting on their knees. The body was then covered with stones. However, these burial sites were not sturdy, allowing hyenas to sniff out the corpse and pull it from its tomb in a practice known as exposure of the corpse.

The Kikuyu, like the Maasai, practiced exposure, discarding their dead to the wild animals. In his biography, Francis Hall claimed to have buried victims of disease himself, since under Kikuyu customary law, corpses ought not to be touched. The Meru, like the Kikuyu, abhor contamination through contact with a corpse. Hence, those who disposed of corpses as well as the family members underwent ritual cleansing by shaving.

But not every Kikuyu threw their deceased to the hyenas; the rich were buried. According to Johnson N. Mbugua, a kĩbĩrĩra was the burial ground where the Kikuyu took their dead. Before burial, they performed rituals which involved a careful wrapping of the body in a sleeping position, with the kĩbĩrĩra facing the homestead. These were elaborate rites, costing sheep and goats beyond the means of many. Kikuyu funeral rites culminated in a full Gũkũra ceremony, which showed the deceased person’s spirit achieving ancestral status.

But not every Kikuyu threw their deceased to the hyenas; the rich were buried.

Today, with the prevalence of Christianity, burial ceremonies even amongst African Christians often involve prayers in a church and at the dead person’s home, alongside traditional rituals.

Four reasons for the growing practice of cremation

The reasons for the growing practice of cremation in Kenya vary. I identify them as individual preference, cultural changes, environmental reasons, and relaxation of religious opposition.

The main reason for cremation in Kenya is honouring the wishes of the departed. For example, in 2002, Archbishop Kuria honoured his wife’s wish to be cremated. According to Maurice Murimi, Kuria’s son-in-law, “It was not the family’s decision but the express choice of our mother.” Archbishop Kuria died three years later, in 2005, leaving a similar will to be cremated. ACK Primate David Gitari did not interfere with his predecessor’s wish. Justifying his stand, Gitari pointed out that the ACK has always respected the family’s decision on interment. Roman Catholics take a similar position, giving the right to choose the church where the funeral rites are to be observed and the choice of the cemetery where the burial will take place to the individual, unless the church forbids it.

Apart from Islam, which forbids cremation, more religions have taken into consideration cremation as a way of disposing of the dead. Although Christian denominations prefer burial, with the exception of the Greek Orthodox Church, all allow cremation. The Kenyan Church is part of other global Christian denominations and has shared these beliefs with them. Anglicans/Episcopalians, Baptists, Lutherans, and Methodists, favour cremation before or after the funeral rite. Presbyterians do not support cremation, but nor do they forbid it.

The ACK proposed changes in her funeral policies accommodating cremation at the 1999 Provincial Synod. Its adopted resolutions stated:

The African culture has not yet accommodated itself to the practice of cremation. But if a Christian in his or her will wishes his body to be cremated, the church will accept that wish.

The Roman Catholic Church prefers cremation to take place after the funeral mass, and demands that the cremains be buried in the ground or at sea or entombed in a columbarium. It forbids the scattering or the keeping of the ashes by the family. Although the Roman Catholic Church pronounced itself on cremation earlier, it was slower in actioning the decision. During Vatican II, the Catholic Church reformed its funeral and burial rites, adopting a more relaxed approach, allowing cremation with one very explicit proviso. The Catholic Church codified this modification in the latest Code of Canon Law:

The Church earnestly recommends that the pious custom of burial be retained; but it does not forbid cremation, unless they chose this for reasons which are contrary to Christian teaching.

But only recently did the Roman Catholic Church issue instructions on cremation; on 25 October 2016, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith addressed the objectionable ideas and practices of cremation.

Christian theologians advocate for cremation as an alternative way of disposing of the dead. Concluding his research on Kikuyu burial traditions, Mbugua urges Christians from the Kikuyu community to embrace cremation as a way of disposing of the dead, as this will reduce funeral costs. Cremation for an adult costs KSh50,000 at the Lang’ata crematorium in Nairobi. Kariokor is much cheaper, where the cost ranges between KSh13,000 for adults and KSh6,000 for children. Further, Mbugua cites lack of adequate space to bury the dead, as a reason for cremation. Cremation should be a workable choice for the people of Nairobi according to Hitan Majevdia of the Nairobi County Health ministry, who also cites scarcity of space, and shortage of cemeteries within Nairobi.

Changing cultural perspectives

Africans are living under the constant pressure of globalization. It is a tension between adopting the modern and jettisoning their traditional practices.

When Maria Louise Okondo, the European spouse of the former minister for labour, Hon. Peter Okondo, had him cremated in 1996, the family accused her of introducing Okondo to foreign customs. She went against Okondo’s extended family’s wish to bury him according to the Luhya-Abanyala customs. Among the Luhya, one’s burial positioning contracts or extends, which has to do with the “mythology or origin of the clan”. Moreover, the kin wished to rid themselves of bukhutsakhali (the breath of the dead), an Abaluhya funerary rite where the bereaved family members shave. Mrs Okondo refused to accede to the family’s wishes, arguing that her husband was no longer bound by Abaluhya customs.

Ruth Okuthe, wife of former Kenyan sports administrator Joshua Okuthe, cremated him in 2009 in accordance with Joshua’s will. His extended family went to court in a bid to stop the cremation but Ruth Okuthe outwitted them. His family buried his empty coffin in a mock funeral ceremony at his Muhoroni home. This was in line with the Luo burial tradition where an empty cenotaph represents the deceased whose body is buried in another location. In the case of a death by drowning or where a body has not been recovered, the Luo bury the yago fruit in the cenotaph or by the lakeshore.

The family of Kibera Member of Parliament Hon. Kenneth Okoth had to honour his wish to be cremated. The individual choice has a chiasma. While African customs often trumped individualism in preference to societal customs, they nevertheless held the will of a dying individual as sacrosanct. The Luo espoused belief in the afterlife, which was integral to the belief that a person’s social status in life and an individual’s last words at death in effect determine his or her relationship with those left behind. They believed the elderly had the power to bless or to curse, and hence their last spoken words could either bless or curse. Thus, the last words spoken at a funeral are binding to the relatives. This was prevalent among the societies that revered the dead.

The communities that previously practiced exposure adopted burial with the coming of Europeans to Kenya; they are bound to change again. Hon. Kenneth Matiba, founder of Ford Asili Party, a leading politician and an opinion leader among the Kikuyu people and Kenyans in general, chose cremation over burial. Matiba is reported to have said in 1994 that he did not want a state funeral or “dancing parties and harambees” upon his death. Another prominent Kikuyu who chose the crematorium over the grave is professional golfer Peter Njiru, who was cremated at Kariokor in 2015.

Environmental reasons

Land scarcity and hygiene and environmental concerns have also contributed to the increased acceptance of cremation as a method of disposing of the dead. Cremation makes better use of land. To reinforce cremation as a Christian practice, William E. Phipps posits: “As land becomes scarcer, cremation is more widely endorsed.” Environmentalists argue that ecologically, cremation is more environmentally responsible. This was the position of Prof. Wangari Maathai, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who died and was cremated in 2011 and her ashes buried at the Wangari Maathai Institute for Peace and Environmental Studies.

The awareness of the benefits accruing from popular Eastern practices has caused them to become accepted worldwide. According to the Cremation Association of North America, the cremation rate within the United States was 48.6 per cent of deaths in 2015, up from 47 per cent in 2014. The association predicted that the rate would reach 54.3 per cent by 2020. The projected rate in Canada was 68.8 per cent in 2015 and 74.2 per cent by 2020. In 2015, 65 per cent of Americans, two-thirds of the people, chose cremation.

Critical correlation

Here we shall explore the critical correlation of the findings on cremation with the normative traditions and interpret the discourse on the disposal of the dead to show its salient aspects and discuss whether cremation is un-Christian and un-African.

CITAM Bishop Dr David Oginde, the most articulate critic of cremation in Kenya, claimed that “Traditional Christian faith considers cremation as inconsistent with orthodox doctrine”. He echoes conservative theologians such as Rodney Decker who took an “active discouragement” position, considering cremation a sin if done as an act of defiance against God.

Opponents of cremation base their argument on the Scriptures which they say are full of examples of burials, although there exists no explicit text commanding Christians to bury their dead. Oginde argues that “one reads nowhere of a godly person cremating the body of one he or she loved [. . .] one does read repeatedly of burying human bodies and Scripture teaches that the burial of the body is an act of faith.” Cremation, according to Oginde, was not acceptable among the Hebrews, except as a punishment as recorded in Leviticus 20:14. The scriptures record the dead bodies of the unfaithful people, such as Achan and his family whom Joshua burned (Joshua 7:25). However, this was the exception rather than the rule (Deuteronomy 21:22, 23).

The communities that previously practiced exposure adopted burial with the coming of Europeans to Kenya; they are bound to change again.

Had Oginde attended to the account of charring Saul’s remains, he might have reached a different conclusion. To salvage the honour of King Saul and of his three sons against the defilement of their corpses by Philistines, the men of Jabesh-Gilead burned and buried their remains (I Sam. 31:8–13). Phipps notes the Bible’s approval of their action where David commended the men of Jabesh-Gilead for the honour they gave to Saul with their action (2 Sam. 2:4–6).

It is difficult to rule out cremation from the Scriptures. Biblical narratives lack uniformity and so gives a conflicting position on cremation. Decker observed that much of the Biblical material is descriptive narrative and not prescriptive. Hence, the Bible never commands, encourages, or condones cremation and it is possible to draw multiple principles from a variety of situations. Despite this, Decker insists inhumation is the most compatible with Christian theology and the most effective in terms of Christian witness in the West. (This essay has not attempted to discuss the question of Christian practice in Eastern cultures or in countries where cremation may be mandated. I have insufficient knowledge of such matters to attempt such a discussion.) However, Decker concedes, “I would not go so far as to declare flatly that cremation is sin. Sometimes it may be acceptable without embarrassment.”

Does cremation offend Christian dogma?

It will be difficult to associate cremation with the new age movement—as Oginde claims—that ushered in cults and philosophies, bringing in a human revolt against God. This claim comports with MacDonald’s assertion that those opposing burial hate Christian customs, ecclesiastical traditions, and have sectarian interest.

The Church refutes regeneration or reincarnation as a denial of individual uniqueness and the resurrection of the body. She affirms that human beings are both physical and spiritual, both of which apply to salvation, and thus challenges the notion of Gnosticism in the first century that viewed the body as evil (Col 2:9). God’s salvation and redemption include both the soul and the body (1 Cor. 7:34; 2 Cor. 4:16; 7:1; Rom. 8:10), which will occur at the resurrection (Rom. 8:23). The human is complete when he/she is both material and immaterial, making the future resurrection imperative.

Opponents of cremation base their argument on the Scriptures which they say are full of examples of burials, although there exists no explicit text commanding Christians to bury their dead.

The separation of soul and body at death implies that man is incomplete until reunited at the resurrection, which is understood as clothing of a naked soul (corpse). However, theologians differ on the state of the corpse. M. Harris holds a monistic anthropology, which expects an immediate resurrection at death. But Decker argues, at “death, the corpse in the grave is referred to as a person. The dead body of Jesus is referred to as ‘him’ not ‘it’” (Mark 15:44-47, see John 11:43). This position that a person—body and soul—is eternal, for which Jesus promised everlasting life, needs scrutiny.

The living believers at Christ’s second coming will get new bodies, while the dead bodies, since buried, will decompose (Eccles. 12:7). The present human bodies count for little for salvation, for God has designated new bodies for believers (1 Cor. 15:42-49; 1 Thess. 4:13-18; Job 19:25-26). At death, the human body rots, just like seed being cast into the earth, dies and rots (1 Cor. 15:36). Given that the body is chemicals, it disintegrates at death as David Wasawo explains in his unpublished memoir We Understand but Darkly:

Are we not mostly made of oxygen, carbon and hydrogen, sixty percent of which are in the form of water? Are we not reminded that a man weighing 150 pounds contains 97.5 pounds of oxygen, 27 pounds of carbon, 15 of hydrogen, 4.5 of nitrogen, 3 of calcium and 1.5 pounds of phosphorus? Added to these are a few ounces each of potassium, sulphur, sodium, chlorine, magnesium, and iron; and traces of iodine, fluorine, and silicon.

Wasawo notes how these elements are combined “to form thousands of very complicated compounds forming parts of cells, tissues, and organs, each performing its allotted function in the sentient being”. But once life is taken out of the body, all these elements revert to the “soil” and to “dust” whence they came—to Mother Nature.

Dignity of the body

The dignity of the human body is a focus of the Church’s attention from birth to death. Unlike other creatures, God made man in His image, hence the respect for the human body. Although Anglican Bishop Peter Njenga defended Mrs Mary Kuria’s cremation, speaking at a thanksgiving service, he voiced a Christian’s objection thus: “I think the big problem with cremation is that people believe cremation subjects the body to torture”. Pope Pius XII affirmed this position while addressing those engaged in the treatment of the blind on 14 May 1956:

The human corpse has been a dwelling place of a spiritual and immortal soul, an essential part of the human person in whose dignity it had a share. Since it is a component part of man and formed in “the image and likenesses of God.”

Through burial, Christians showed reverence for the body in view of the future resurrection. As Normal Geisler argues, “Burial preserves the Christian belief in the body’s sanctity,” and the Church developed meticulous funeral rites where some churches use incense and holy water with prayers that the Lord receives this person into paradise. Burial became synonymous with the dignity of the individual’s body, as Oginde asserts, “For a corpse to be burnt by fire or left unburied to become food for beasts of prey, was the height of indignity or judgment.” However, Brigham refutes that proper burial was essential for an individual’s bliss in the afterlife; sometimes undignified disposal of the body provided lasting witness. As St. Augustine observed in The City of God:

And so there are indeed many bodies of Christians lying unburied; but no one has separated them from heaven, nor from that earth which is all filled with the presence of Him who knows whence He will raise again what He created… Wherefore all these last offices and ceremonies that concern the dead, the careful funeral arrangements, and the equipment of the tomb, and the pomp of obsequies, are rather the solace of the living than the comfort of the dead.

Christians regard the human body as a temple of the Holy Spirit but this role ceases at death. The body is valuable while one is alive. Decker concedes that the Holy Spirit does not dwell in our bodies after death but makes limping claim of the body being still united to Christ, “. . . if the body is a member of Christ due, in part to the resurrection.” A person’s existence does not end at death, as materialists believe. For, as White notes, a connection and continuity between the human soul and body exists; otherwise a future resurrection would be unnecessary.

Phipps contends, “The allegedly preserved body is a Promethean rejection of Isaiah’s judgment that ‘all flesh is grass’ and Paul’s claim that ‘flesh and blood cannot inherit the Kingdom of God’. Since death neither destroys the person nor reduces his or her uniqueness and individuality, cremation doesn’t constitute an objective denial of these dogmas.” MacArthur states, “So cremation isn’t a strange or wrong practice—it merely accelerates the natural process of oxidation.” Christians should accept cremation when it meets the demands of due respect and dignity for the body, and the ashes are treated with the same dignity. Further, Phipps suggests, “a memorial worship service after cremation sets the transitoriness of the physical in bold relief against the everlastingness of the spiritual. The ‘consuming fire’ has transformed but not destroyed the essential self of the person honored at the service.”

Burial was not inherently Christian; since Christians adopted and developed this tradition from pagan and Jewish practices, under different circumstances, they could have adopted cremation.

Resurrection of the dead

Given that Jesus himself was buried and raised bodily from the dead, a Christian’s burial was to be witness to the resurrection yet to come. Christians assume that burials confer the symbolism of resurrection, which gives them a deeper religious significance. Indeed, MacDonald argues for laying the body to rest in the grave to await the call to general judgment on the last day rather than submitting the human corpse to extermination by fire.

Accepting this view implies that resurrection is physical, a position Phipps disputes, stating:

Paul did not believe that the residual dust in a tomb would be the substance of a new heavenly organism. When the apostle writes about ‘the resurrection of the dead,’ he does not mean the reassembling and the reanimation of the corpse. The expression ‘spiritual body’ (1 Cor. 15:44) which he uses does not refer to the physical skeleton and the flesh that hangs on it. Rather, in modern terminology, it means the self or the personality. Paul’s view is compatible with body disposal by cremation. Contrariwise, those who adamantly advocate earth burial because it enhances resurrection have a weak New Testament foundation on which to stand.

What happens to the body after death is immaterial. The cremation of the body has no effect on the soul and nor does it hinder God’s power from raising a body to life again. Thus, the dead will change like the dead seed which is quickened and raised in stalk, blade, and ear. The dissolution and corruption of the body by death is not a hindrance to its resurrection. If God can quicken a rotten seed, turning it productive, why should we consider it incredible that God should quicken dead bodies?

So, it does not matter to God whether a person’s body was buried, cremated, lost at sea, or eaten by wild animals (Revelation 20:13). The Almighty can re-create a new body for the person (1 Cor. 15:35, 38). For cremation does not affect the soul, nor does it prevent God from raising up the deceased body to new life (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith).

Is cremation un-African?

While some Christians accept cremation as a choice today, many more consider this practice too radical and foreign.

Communities such as the Meru, Kikuyu, Kamba, and Kalenjin, which practiced exposure of corpses, learnt to bury; they should find cremation better than customary practices. Justifying his choice of cremation, Matiba argued, “After all, the Kikuyu traditionally never buried their dead. They used to take the bodies into the forest to be devoured by hyenas. Was that not wisdom?”

Until now, Africans have held that the dead affect the living but westernization among Kenyans is eroding the belief that the spirits of the dead have an influence on the living, that they would be haunted were they to dispose of their dead differently, that the deceased may become a malevolent spirit. Upon one’s death, an “exact” burial bounded by abundant religious formalities allows them to become an ancestor. Hence, the weight given to “proper” death rites, which ‘guarantee protection’ for the living, more than they secure a safe transition for the dead.

Burial was not inherently Christian; since Christians adopted and developed this tradition from pagan and Jewish practices, under different circumstances, they could have adopted cremation.

Yet, here is a paradox: while the Luo rejected cremation because they held the belief that the dead influenced the living, and adhered strictly to their customary funeral rites to stop the dead from tormenting the living, Dr Ocholla-Ayayo explains that under exceptional circumstances the Luo permitted incineration; they exhumed and burned the remains of a departed one believed to be haunting their kin. This recognition of the impotent dead among Luo Christians has blunted the fear of ancestral wrath, and removed the traditional obstacle to cremation.

Theory construction

In the construction stage, the paper applies the empirical data and theological discourse to offer a theory for action and, thus, revises the present praxis. The theory is aware of the presuppositions of cremation.

As the Church expands, she confronts diverse human conditions, encounters new cultures not within the experience of the biblical traditions from which Christians can draw answers. Where we have no concrete biblical injunctions to guide us on how to dispose of our dead, its broad narratives should help us to frame firm conclusions, which ought to be theological considerations, cognizant of our various cultural issues.

The first significant decision by the Council in Jerusalem, recorded in Acts 15, which declared that the new gentile Christians did not have to enter Jewish religious culture, opened Christianity to the adoption of the cultures it had entered. The lack of a Christian culture in the way we have an Islamic culture, points to the cultural diversity and flexibility built into the Christian faith from the beginning; Christians didn’t have to receive circumcision or keep the Jewish law, bringing to an end a tribal mode of faith. This stand opened Christianity to other things.

Christianity lacks a specific Christian lifestyle. So, Christians are to work out, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, a way of being Christians in their context. Since disposing of the dead is a cultural construct, not a doctrinal edict, like in Islam, the decision to bury or cremate ought to be theological. Long before the Vatican II changes, McDonald observed, the Church allowed Japanese Catholics to be cremated. Cremation as an age-old national custom was compulsory in Japan. However, the bishops in Japan negotiated and were allowed to bury priests and members of religious orders and congregations.

The foregoing theological argument and the critical correlation of the findings on cremation with the normative traditions established above, provide the basis on which Christians today can explore cremation instead of burial. Although both the Anglicans and Roman Catholics settled the theological questions, they never went beyond their pronouncement. The ACK, for instance, did not develop cremation protocols or liturgies despite having undertaken funeral reforms. Beyond the resolution, they have put little effort into preparing Christians for cremation. Moreover, general Christian cremation infrastructure remains undeveloped.

“After all, the Kikuyu traditionally never buried their dead. They used to take the bodies into the forest to be devoured by hyenas. Was that not wisdom?”

The Church should set cremation protocols in tandem with Christian dogma. Through the Holy Office’s instruction, the Roman Catholic Church maintains that those who choose cremation must not deny the dogmas, such as the immortality of the human soul and the bodily resurrection of the dead. Therefore, cremation undertaken in adherence to Christian dogma would enhance, not mute, the expression of Christian faith.

Where Christians choose cremation over burial, their wish ought to be clarified to avoid conflict upon death. George Omwansa, a council member of the Lawyer Society of Kenya who has handled several cremation disputes, observed that in such cases not the entire family was aware of the cremation wishes of the departed, leading some relatives to oppose cremation in favour of burial, thus causing trouble.

The Church should provide families and individuals opting for cremation with guidelines to help them in their decisions, and to ensure that they bury the cremains in a dignified manner. A Christian cremated in the recommended manner may choose, for example, to be buried with his ancestors or at a cemetery or any other sacred place (e.g., a church, a columbarium, or a mausoleum). And while the memorial service should remain unchanged, there is a need to create a liturgy and order of service to assist the clergy when dealing with a cremation service and committal of the cremains.

Since disposing of the dead is a cultural construct, not a doctrinal edict, like in Islam, the decision to bury or cremate ought to be theological.

There is also a need to develop public and Christian crematoriums. The largest crematorium in Kenya is the Hindu crematorium in Kariokor, where most cremations occur. In effect, since Hindus run most crematoriums in the country, it is easy to associate cremation with Hinduism or modern-day agnostics.

I do not here propose a biblical response to cremation, but a presentation of the Christian core beliefs to clarify the faith challenge that disposing of the dead presents. I have established a theologically informed course of action that sets cremation as an alternative way of disposing of the dead, consistent with the existing traditions of the Christian faith and African customs. Besides discussing the occurrence of cremations in Kenya, I have discerned why people are choosing cremation over burial as an interpretive element of practical theology. In its discourse, the study has exposed the salient aspects surrounding cremation, establishing that it does not offend Christian dogma, and nor does it assault African customs.

In offering a plan of action to revise the present praxis, this study has proposed a way forward for Kenyan Christians, having established that cremation offers Christians a valid and acceptable alternative to traditional burial.