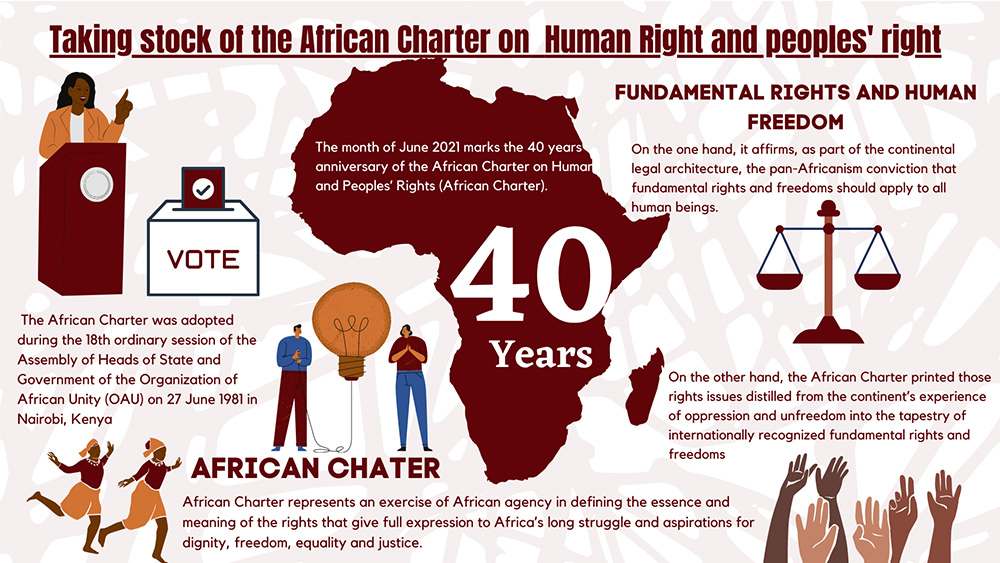

The month of June 2021 marks the 40 years anniversary of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (African Charter). The African Charter was adopted during the 18th ordinary session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) on 27 June 1981 in Nairobi, Kenya. On 28 June 2021, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the body established to oversee the implementation of the African Charter, convened a high-level event to take stock of the four decades journey of the African Charter.

The African Charter occupies a historical, political and symbolic significance at par with such similar instruments as the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. On the one hand, it affirms, as part of the continental legal architecture, the pan-Africanism conviction that fundamental rights and freedoms should apply to all human beings. On the other hand, the African Charter printed those rights issues distilled from the continent’s experience of oppression and unfreedom into the tapestry of internationally recognized fundamental rights and freedoms.

In celebrating this 40th birthday of the African Charter, it is worthwhile to adequately appreciate the context and the historical background of the African Charter. Here, as in other areas of life in contemporary Africa, history matters. It does so profoundly as it co-constitutes our present context. A doctrinal approach to the catalogue of rights, freedoms and duties articulated in the Charter offers us only a very limited understanding of both their meaning and content and significantly their political, socio-economic and international importance vis-à-vis contemporary challenges of respect for and protection of human and peoples’ rights.

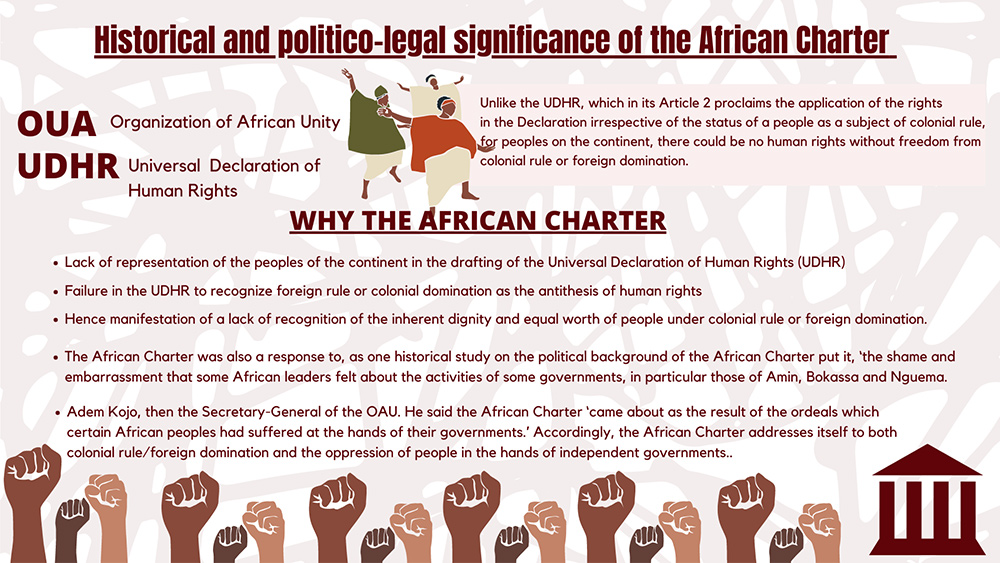

Historical and politico-legal significance of the African Charter

So why the African Charter? Why its adoption by the OAU in June 1981? These are questions for which there is no single answer but are worthy of serious investigations and study. I therefore would not wish to go into details. I would rather limit myself to noting briefly some of the fundamental conditions that led to the adoption of the African Charter.

In one way, the African Charter represents an exercise of African agency in defining the essence and meaning of the rights that give full expression to Africa’s long struggle and aspirations for dignity, freedom, equality and justice. The articulation of the African Charter made up for not only the lack of representation of the peoples of the continent in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) but also for the failure in the UDHR to recognize foreign rule or colonial domination as the antithesis of human rights and hence manifestation of a lack of recognition of the inherent dignity and equal worth of people under colonial rule or foreign domination. Unlike the UDHR, which in its Article 2 proclaims the application of the rights in the Declaration irrespective of the status of a peoples as a subject of colonial rule, for peoples on the continent there could be no human rights without freedom from colonial rule or foreign domination. It is worth recalling that in Africa’s political history as far back as the 1919 Pan African Congress and the works of the foremost thought leaders including Frantz Fanon, Nnamdi Azikiwe and Kwame Nkrumah colonial rule and foreign domination were treated as negation of human rights.

Accordingly, the African Charter addresses itself to both colonial rule/foreign domination and the oppression of people in the hands of independent governments.

Second, the African Charter was also a response to, as one historical study on the political background of the African Charter put it, ‘the shame and embarrassment’ that some African leaders felt about the activities of some governments, in particular those of Amin, Bokassa and Nguema. This is best illustrated by what the Chairperson of the OAU President Tolbert said in 1979 in his opening address to the AOU summit – ‘the principle of non-interference had become ‘an excuse for our silence over inhuman actions committed by Africans against Africans…The provisions concerning human rights must be made explicit.’ That this shame and embarrassment was a factor behind the OAU decision for the elaboration of a ‘Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ was buttressed by the late Adem Kojo, then the Secretary-General of the OAU. He said the African Charter ‘came about as the result of the ordeals which certain African peoples had suffered at the hands of their governments.’ Accordingly, the African Charter addresses itself to both colonial rule/foreign domination and the oppression of people in the hands of independent governments.

At this point, it is worth recalling that a similar experience in the 1990s led the continent to the adoption under the AU Constitutive Act of the paradigmatically novel principle of intervention in cases of grave circumstances under Article 4 (h). The parallel becomes apparent from President Mandela’s speech during the 1994 OAU summit in Tunis where he expressed this sense of ‘shame and embarrassment’ when he said ‘Rwanda stands out as a stern and severe rebuke to all of us for having failed to address Africa’s security problems. As a result of that, a terrible slaughter of the innocent has taken place and is taking place in front of our very eyes.’

These historical references make it clear that the African Charter is the first legal instrument to pierce the veil of sovereignty that excluded any scrutiny of how independent African states treated people under their jurisdiction. In doing so, the African Charter served as the legal predecessor to and laid the foundation for Article 4(h) of the Constitutive Act, hence as the foundation for the principle of non-indifference.

One of the drafters of the African Charter, The Gambian jurist Hassan Jallow thus remarked in his book The Law of the African (Banjul) Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights ‘the very notion of creating machinery for the promotion and protection of human rights was itself nothing less than revolutionary in a continent where and at a time when the African states were ultra-jealous of their national sovereignty even and brooked no interference in what they regarded as their internal affairs.’

The African Charter also affirms that human rights are not simply an embodiment of abstraction from an ideal theory about the human. Importantly, they are products of specific historical experiences and civilizations. In this sense, at one level the African Charter is an illustration of the late Christof Heyns theory of the struggle approach to human rights. Viewed from this perspective, the African Charter is in part an exercise to articulate catalogue of rights geared towards the conditions of oppression that historically robbed the peoples of the continent of their humanity as Africans and continue to impede their access to full measure of fundamental rights and freedoms. The African Charter thus gives recognition to the need to ‘eliminate colonialism, neo-colonialism, apartheid, Zionism, and to dismantle aggressive foreign military bases and all forms of discrimination, particularly those based on race, ethnic group, color, sex, language, religion or political opinion’.

The African Charter represents an exercise of African agency in defining the essence and meaning of the rights that give full expression to Africa’s long struggle and aspirations for dignity, freedom, equality and justice

At another level, the Charter echoes the opening remarks of President Leopold Sedar Senghor at the first expert meeting for the drafting of the Charter in Dakar in 1979, where he counselled the experts to draw inspiration from and keep constantly in mind ‘our beautiful and positive traditions and civilization’ and ‘the real needs of Africa.’ The result of this has been not only the articulation of duties of individuals by the Charter premised on the Ubuntu philosophy of coexistence and harmony between the individual and the society, but also the recognition of the inseparability and interdependence of civil and political rights and economic, social and cultural rights.

In terms of ‘the real needs of Africa’, the African Charter accorded a prime place of honor to peoples’ rights on par with human rights as vividly captured in the title of the African Charter. In so doing, President Senghor pointed out, ‘We simply meant …to show our attachment to…rights which have a particular importance in our situation of a developing country.’ Elaborating further, he pointed out, ‘[w]e wanted to lay emphasis on the right to development and the other rights which need the solidarity of our states to be fully met: the right to peace and security, the right to a healthy environment, the right to participate in the equitable share of the common heritage of mankind, the right to enjoy a fair international economic order and, finally, the right to natural wealth and resources.’

While much of its promises have been honored by breach rather than compliance, the African Charter thus broke new ground in both the politico-legal evolution of the continent and international legal recognition of fundamental rights and freedoms. At the global level, it contributed to the enrichment of the international corpus of human rights. It did so both by giving equal legal status to civil and political rights on the one hand and economic and social rights on the other hand and by enshrining the collective rights of peoples and the duties of individuals.

Contemporary status and significance of the African Charter

Today, the African Charter enjoys not only a status of customary international law but also that of being akin to the basic law of the continent. It is not simply one of the few OAU/AU treaties with universal ratification. It is perhaps the only human rights instrument that is widely cited not only in large number of continental legal and policy documents but also at sub-regional and national levels. The African Charter also inspired the adoption of various human rights and democracy and governance norms within the OAU and its successor the African Union in the 1990s and since. Along with other human rights instruments it inspired, the African Charter continues to serve as source of inspiration in the elaboration of national bills of rights and various laws giving effect to specific human rights.

The African regional human rights system that the African Charter established also contributed to the recognition of the legitimacy of the works of civil society organizations, human rights defenders, political opposition and the media, despite the increasing assault to which they have in recent years been subjected. Accordingly, the African Commission has accorded institutional recognition by extending observer status to large number of non-governmental organizations working in the field of human rights pursuant to Article 45 (1)(c) of the African Charter.

The African Charter is not simply a historically grounded human rights treaty that speaks to both the generality of human rights issues and the human and peoples’ rights issues in Africa emanating from our specific historical experiences and socio-economic and political conditions. It is also a living document. As such, it operates to respond to the human and peoples’ rights issues also of the present and the future.

Article 45 (1) (b) tasks the African Commission ‘to formulate and lay down principles and rules aimed at solving legal problems relating to human and peoples’ rights and fundamental freedoms.’ Additionally, in mandating the African Charter to apply the rights and duties in the Charter to specific cases that may be referred to the Commission by States or ‘other communications’, the Charter recognises the need for its constant interpretation and application to make the rights and duties in the charter responsive to both the specific cases and the evolving needs of Africa. In commanding the African Commission under Article 60 to draw inspiration from international law on human and peoples’ rights, the Charter affirms its interconnectedness with international human rights. In doing so, the Charter also opens its provisions to be enriched through cross-fertilization. Based on Articles 45 (1) (b), 47, 55 and 60 of the African Charter, the jurisprudence of the African Commission and since 2006 the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights, have clarified some of the gray areas in the African Charter and the ‘claw back clauses’ attached to some of the rights in the Charter, which inspired the most criticism against the Charter in the early years of the Charter’s life.

The African Charter is unique in combining its particularistic and internationalist features in other symbiotic ways as well. Thus, in articulating duties of individuals as embodying one of its distinguishing features, it states in Article 27 (1) that individuals owe duties, among others, to the international community.

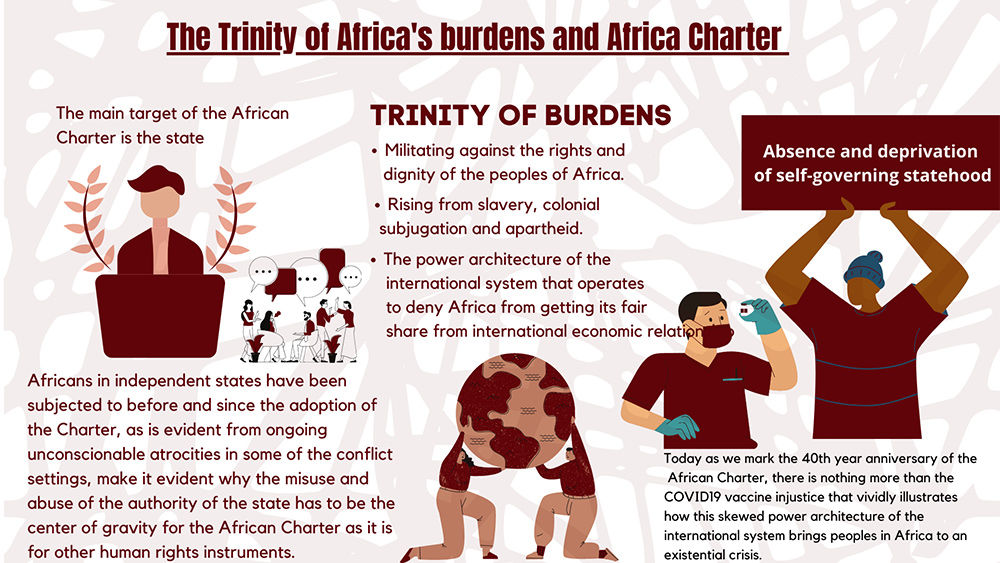

The trinity of Africa’s burdens and the African Charter

Like other human rights treaties, the main target of the African Charter is the state. The experience of the grievous human rights violations to which Africans in independent states have been subjected to before and since the adoption of the Charter, as is evident from ongoing unconscionable atrocities in some of the conflict settings, make it evident why the misuse and abuse of the authority of the state has to be the center of gravity for the African Charter as it is for other human rights instruments.

In the European experience, it was the totalitarianism to which the state is disposed and the threat this posed both to the rights and freedoms of individuals and to peace and security that inspired the development of a system of human rights. However, for the African Charter the authoritarian impulses of the state is only one (but never the only) source of threat to human rights and fundamental freedoms.

As I observed in the opening statement for the 28th extra-ordinary session and further highlighted below, indeed authoritarian rule and the bad governance and repression arising from it represents the first of the trinity of burdens militating against the rights and dignity of the peoples of Africa. The second of the trinity of burdens is the burden of history (arising from slavery, colonial subjugation and apartheid). That the burden of history constitutes an important area of preoccupation as a source of unfreedom for the African Charter can be gathered both from the preamble and the substantive text of the African Charter.

A doctrinal approach to the catalogue of rights, freedoms and duties articulated in the Charter offers us only a very limited understanding of both their meaning and content and significantly their political, socio-economic and international importance vis-à-vis contemporary challenges of respect for and protection of human and peoples’ rights

In the landmark case, SERAC v. Nigeria, our Commission, thus remarked that the origin of some of the provisions of the African Charter, in the particular instance Article 21, is to be traced to ‘colonialism, during which the human and material resources of Africa were largely exploited for the benefit of outside powers, creating tragedy for Africans themselves, depriving them of their birthright and alienating them from the land.’ On how this experience affects present day Africa, the Commission stated that the ‘aftermath of colonial exploitation has left Africa’s precious resources and people still vulnerable to foreign misappropriation.’

As pointed out above, in the African experience, the historically grounded normative foundation for human and peoples’ rights has been the absence and deprivation of self-governing statehood to the peoples of Africa. The structural weaknesses and flaws that characterizes the post-colonial African state is a manifestation of this burden of history. As Adom Getachew highlighted, in her landmark study Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-determination, this inherited burden makes ‘new and weak postcolonial states vulnerable to arbitrary interventions and encroachments at the hands of larger, more powerful states as well as private actors,’ thereby severely inhibiting their capacity for shouldering their responsibilities to meet the human rights needs of the peoples of the continent.

The third of the trinity of burdens is thus the power architecture of the international system that operates to deny Africa from getting its fair share from international economic relationship. In stating in the preamble that the peoples of Africa ‘are still struggling for their dignity and genuine independence,’ the African Charter is expressing its recognition of the adverse impact not only of the past but also the burden Africa bears from the unjust power arrangement of the international system. It thus affirmed that ‘it is henceforth essential to pay particular attention to development …and that the satisfaction of economic, social and cultural rights is a guarantee for the enjoyment of civil and political rights.’ These preambular statements and the substantive rights, in particular collective rights of peoples, expand the conception of injustice undermining the full enjoyment of human rights to encompass the ways in which the international system frustrates the rights of peoples to freely determine their economic and social development according to the policy they have freely chosen as envisaged in Article 20 of the African Charter.

Today as we mark the 40th year anniversary of the African Charter, there is nothing more than the COVID19 vaccine injustice that vividly illustrates how this skewed power architecture of the international system brings peoples in Africa to an existential crisis.

The third wave of COVID19 pandemic is gathering pace, with more devastating impact than previous waves. It claims the lives of increasing number of peoples including the highly limited skilled health care workers due to lack of access to the COVID19 vaccine and deals a serious blow to the economies of the continent. African countries, like others in the global South, are witnessing that their concerns – that the protection given to pharmaceutical companies under the treaty on intellectual property rights will prevent them from protecting the right to health of their citizens – is being born by events. Together with major European countries, pharmaceutical companies are blocking the temporary waiver of the application of patent protection to COVID19 vaccines, key for making the generic production of these vaccines on the continent for ending the current artificial scarcity. As Strive Masiyiwa, chief of AU’s vaccination acquisition task team pointed out, Africa’s inability to access the vaccine is ‘a product of the deliberate global architecture of unfairness.’

No. We are not all together on this. Africa, we are on our own. Again. In the 1990s with civil wars and the implosion and collapse of states ravaging parts of Africa, the continent was left on its own. In the apt description of the late former Secretary-General of the UN Kofi Annan, Africa was left ‘to fend for itself’. As in the past, Africa rose to this challenge. The OAU transformed into the AU. In pursuit of fending for itself, Africa put in place institutions and processes for resolving conflicts, anchored on the Protocol to the Constitutive Act Establishing the Peace and Security Council.

In the face of the existential crisis facing Africa from the COVID19 vaccine injustice today we have to ask the difficult questions including – what leadership and policy failures have led Africa to be exposed to this existential threat? Will today’s leaders rise to this challenge, as earlier leaders did, by creating the conditions for building the requisite strategic infrastructures for protecting the health people so that Africa will never again face the injustice of denial of access to medical supplies including vaccines, born out of the skewed power structure of the international system?

The generation marking the 40th anniversary of the African Charter, betraying its mission?

The 40th anniversary is an occasion for thanks giving for those who bequeathed us this fine African Charter. I wish in particular to pay homage to first the distinguished Senegalese Jurist Judge Keba Mabaye who, more than any other, played the role of being on the one hand a strategist and campaigner for securing the buy in within the OAU of the idea of the African Charter and on the other hand the lead drafter of the African Charter.

I also equally wish to extend our profound gratitude to President Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal and President Dawada Jawara of The Gambia for initiating the resolution for the adoption of the African Charter and for providing the guidance and support for the drafting of the African Charter. It is worth noting that Senghor’s opening address to the first expert meeting for the drafting of the African Charter served not only as the terms of reference but also as the intellectual guide for elaborating the contents of the Charter.

Our deep gratitude also goes to the then Secretary-General of the OAU Adem Kojo who threw his full weight behind the implementation of OAU Decision 115(XVI) mandating the drafting and worked tirelessly for its adoption.

The generation of Mbaye, Senghor and Kojo discovered its mission and fulfilled it. We owe today’s celebration of the 40 years birthday of our Charter to this.

For the generation celebrating the 40 years of Our Charter, have we discovered our mission? Will we fulfil it, or betray it?

As to the mission of this generation, to which we are all a part, I am sure you agree with me that it lies in rendering the rights and freedoms of the African Charter meaningful in the lives of the masses of our peoples. Will we fulfill this mission by overcoming the challenge of implementation of the African Charter and by confronting the human rights challenges of our time namely – the deadly democratic governance deficit, widespread poverty and deepening inequality, pervasive gender oppression, the rising insecurity and violence and the climate emergency?

All the indications are that, we are on course for betraying this mission.

‘How else can we explain the fact that in 2021 as in the 1990s we have the conditions forcing ‘millions of our people, including women and children, into a drifting life as refugees and internally displaced persons, deprived of their means of livelihood, human dignity and hope’?

Second, the African Charter was also a response to, as one historical study on the political background of the African Charter put it, ‘the shame and embarrassment’ that some African leaders felt about the activities of some governments, in particular those of Amin, Bokassa and Nguema

How else can we explain 29 million people and counting being displaced and forced to flee their country unless states are failing to shoulder their responsibilities under the African Charter?

How can this be possible unless those entrusted with managing the affairs of our societies are betraying the trust of the public in pursuit of their own narrow self-interest thereby perpetuating the vicious cycle of misgovernance and authoritarianism?

It cannot be that we continue to have millions of our brothers and sisters forcibly displaced in states with even the most basic attributes of statehood, in societies with responsible leadership and in a continent with effectively functioning institutions.

It is indeed an indictment on all of us that we have sisters and brothers who expressed their thanks to the COVID19 virus for being provided with water, a basic necessity to which they have been denied access by leadership and policy failure of our governments. How is it that while the resources of the continent are fueling the development of other parts of the world, we are not able to provide even for the most basic necessities of life for the masses of our people? How is it that the leaders entrusted with the management of our affairs indulge in the embezzlement of resources that are meant for securing health workers and the public from the COVID19 pandemic?

What more represents the betrayal of the mission of this generation for translating the African Charter into reality than the way the Charter is observed by being routinely breached through not only the closing of the civic space, the assault on civil society, human rights defenders and the media but also the indiscriminate attacks against civilians and the display of complete lack of regard to the sanctity of human life in the various conflict settings on our continent and the attendant total impunity?

What is more to show how the leaders of the continent are failing the public than the deepening sense of despair that is pushing our people, particularly the youth, to embark on the perilous journey across the Sahara for crossing the Mediterranean Sea despite the death of no less than 20,000 migrants in only five years on this sea?

It is indeed a betrayal of epic proportions that our societies could not assure women and girls a life free from violence so much so that there is no place, from home to the work place and even places of worship, where they can feel safe and free from violence. How else can we explain the fact that sexual and gender-based violence have become the other pandemic within the COVID19 pandemic in nearly all our societies?