President Uhuru Kenyatta’s family, the political dynasty that has dominated Kenyan politics since independence, for many years secretly owned a web of offshore companies in Panama and the British Virgin Islands, according to a new leak of documents known as the Pandora Papers.

The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations.

Other world leaders found in the files include the King of Jordan, the prime minister of the Czech Republic Andrej Babiš and Gabon’s President Ali Bongo Ondimba.

The documents were obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and seen by more than 600 journalists, including reporters at Finance Uncovered and Africa Uncensored, as part of an investigation that took many months and spanned 117 countries. Though no reliable estimates of their net worth have been published, the Kenyattas are regularly reported to be one of the richest families in the country.

The Kenyattas’ offshore secrets were discovered among almost 12 million documents, largely made up of administrative paperwork from the archives of 14 law firms and agencies that specialise in offshore company formations.

They are well known in Kenya as the owners of a vast business empire, including significant interests in the banking, insurance and media sectors, as well as hotels, agricultural land and the large Brookside dairy on the outskirts of Nairobi.

But what has not been known is their activity through tax and secrecy havens, maintained by a network of bankers, advisers, offshore service providers and front figures.

Seven members of the Kenyatta family are revealed through the Pandora Papers as being variously connected to 11 offshore companies and foundations.

The documents reveal that family members have used offshore companies to own three properties in the United Kingdom. One, a flat near Westminster in London, now worth an estimated £1m, was until this summer rented out to a British Member of Parliament, although she did not know who owned it.

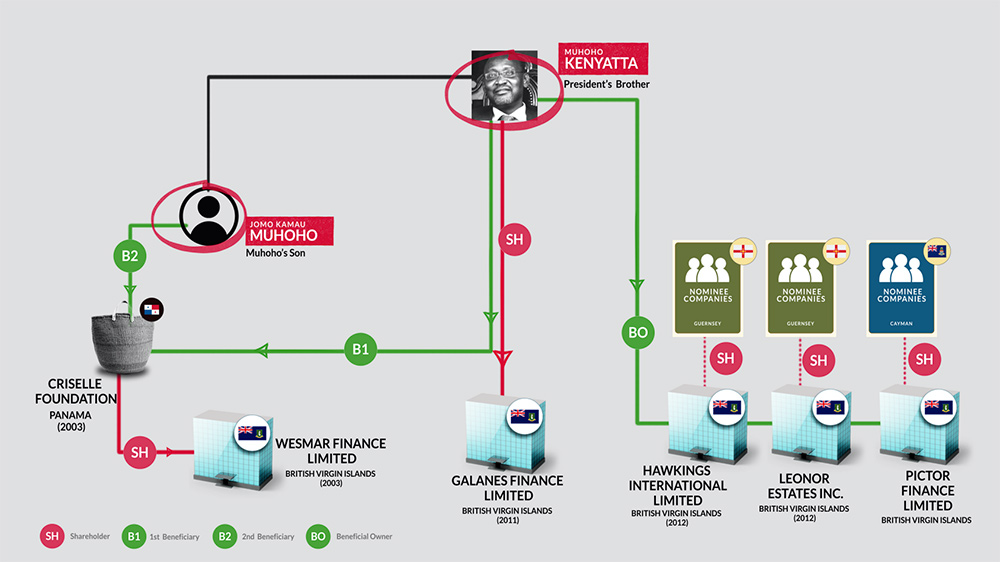

The Pandora Papers also show that Muhoho Kenyatta, the president’s younger brother who manages large sections of the family’s businesses, owned an offshore company with a portfolio of cash, stocks and bonds worth $31.6m in 2016.

Other documents in the leak show a foundation set up in Panama in 2003 for the president’s now 88 year old mother, “Mama” Ngina Kenyatta. Upon her death, all the assets held in the foundation were to pass to her son, Uhuru.

The Pandora Papers contain only a handful of clues about the purpose of the Kenyattas’ offshore interests or what funds and assets they might have placed in these secretive entities.

One document simply says a company in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) had been set up by Kenyatta family members with “savings from their family and their activities”.

In 2018, President Kenyatta (pictured below in Nairobi last week) was asked about his family wealth during an interview on the BBC’s Hardtalk programme. He said: “I have always stated, what we own, what we have, is open to the public. As a public servant, I am supposed to make my wealth known and we declare every year.

The Pandora Papers also show that Muhoho Kenyatta, the president’s younger brother who manages large sections of the family’s businesses, owned an offshore company with a portfolio of cash, stocks and bonds worth $31.6m in 2016

“And I have always said: ‘If there is an instance where somebody can say that what we have done or obtained has not been legitimate,’ say so: we are ready to face any court.”

Jack Blum, an American financial crime lawyer and former staffer on the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said: “If you see that a prominent political family has set up offshore arrangements it certainly would pique one’s interests. You would really have to begin to investigate further because the question would be: Have state assets… been moved and used for the benefit of the individuals involved?”

However, Blum added: “Now, can we say with certainty that the simple use of [offshore companies] is evidence of some kind of criminal activity? I would have to say ‘No’. You have to do a lot more work.”

The Pandora Papers show no evidence that state assets have been stolen or hidden in offshore entities controlled by the Kenyattas.

We tried to contact President Uhuru Kenyatta, his brother Muhoho, his mother Ngina and all relevant members of the Kenyatta family, as well as the president’s office in Nairobi. We asked why they had set up complex corporate structures in some of the world’s top secrecy havens, how much money they had taken offshore and where that money came from. We also asked whether they still used the entities and if so what assets they currently contain.

No-one acknowledged or responded to our letters, emails, phone calls and texts.

There is nothing unlawful about using secrecy structures or making overseas investments. Many wealthy families choose to spread their investments overseas, particularly when their home country faces political or economic turmoil. This is known as capital flight.

However, capital flight — whether lawful and illicit — often drains local investment and increases inequality.

Attiya Waris, Professor of Fiscal Law at the University of Nairobi, said that when ruling elites are discovered to have parked cash offshore, it “is a signal to the rest of the economy that they can do the same”.

She said: “The kind of knowledge on how to do this circulates among professional classes such as lawyers and accountants and they use it to implement the system for others, drawing even the middle classes into engaging with capital flight.”

The Pandora Papers contain only a handful of clues about the purpose of the Kenyattas’ offshore interests or what funds and assets they might have placed in these secretive entities.

Transparency and anti-corruption campaigners have long argued public officials should fully disclose their assets and earnings.

Waris said while complete transparency was never realistic, the concept itself is critical, particularly when countries are trying to rebuild themselves in the wake of the global pandemic.

“The greater the disparities in wealth are in a country, the more you have social problems,” she added.

Under Kenyan law, President Kenyatta is required to make asset declarations for him and his wife, though they are not made public. However, as in most other countries with such requirements, asset disclosure rules do not extend to the wider family.

The findings from the Pandora Papers come as Kenya enters an election period. President Kenyatta is constitutionally bound to step down from office in 2022 after eight years in office — two terms that have seen improved infrastructure yet concerns about inequality and national debt.

First Family

President Kenyatta has carefully nurtured the reputation of the country’s “first family”. It is a family whose history is tied inextricably to the country’s independence and a business empire employing thousands of people.

Uhuru’s father, Jomo Kenyatta, swept to presidential power as a near-penniless independence activist in 1963, ushering in the birth of a new republic.

His status and reputation as the father of the nation grew. So too did his family’s wealth.

But by the time he died in 1978, there were already murmurs.

As noted in a now declassified report by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), written days after Jomo’s death, there were allegations of controversial land dealings involving the Kenyattas.

The report said funds provided by foreign governments — earmarked to pay for redistribution of land from colonial settlers back to landless Kenyans — had instead allegedly been used by the Kenyattas and their associates to buy land for themselves.

US intelligence officers wrote that there was “growing public disenchantment with the Kenyatta clan’s economic monopoly”.

While Jomo Kenyatta himself owned only about half a dozen properties, on roughly 4,000 hectares of land, his fourth wife Mama Ngina owned at least 115,000 hectares including a large ranch, two tea plantations and three sisal farms, the report said.

The Pandora Papers show that in the late 1990s, Swiss wealth advisers had begun helping with the financial affairs of Mama Ngina and other members of her family.

The Swiss advisers, in turn, used an offshore law firm called Alemán, Cordero, Galindo & Lee — or Alcogal.

The Pandora Papers include a leak of thousands of documents from Alcogal.

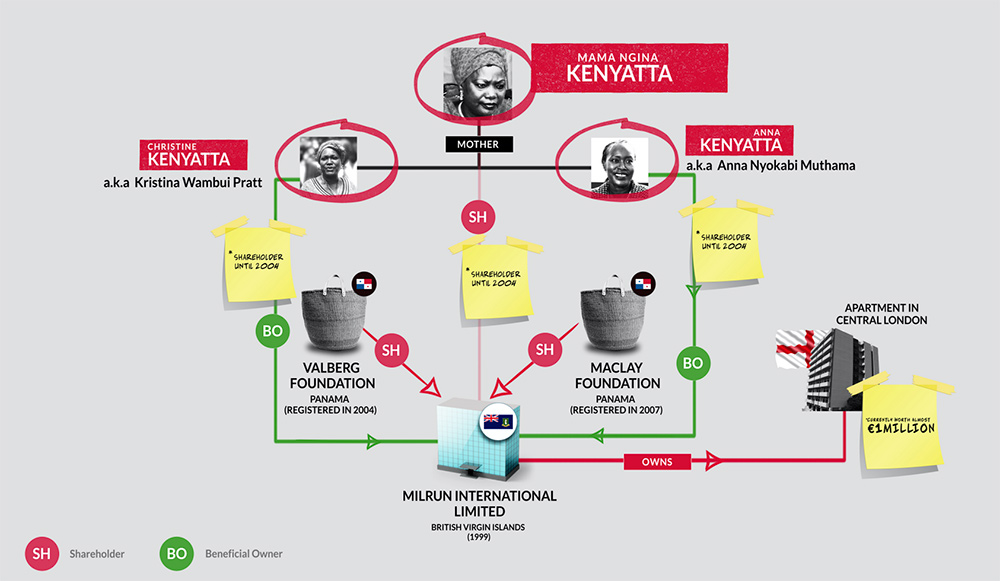

They show that in 1999, Alcogal incorporated a BVI registered company called Milrun International Ltd for Mama Ngina, a minority shareholder, and her two daughters.

Alcogal also provided the registered office for Milrun and supplied Alcogal staffers to act as the company’s official directors.

The result, explained in the diagram below, was an entirely anonymous company, with an address and directors that could not be traced back to the true beneficial owners.

This company was used a year later to buy an apartment thousands of miles from Kenya and Panama, in Westminster, central London, for £280,000.

The Pandora Papers show that the Kenyatta daughters still owned Milrun until at least 2017. We asked them if they still owned the company but they did not respond.

Today, Milrun is still listed on UK Land Registry records as the proprietor of the apartment — now estimated to be worth £1m.

Until this summer, Emma Hardy, a British Labour party MP, rented the apartment when away from her constituency on parliamentary business. As she did so, she lawfully reclaimed £2,600 a month in rent expenses from state funds.

Attiya Waris, Professor of Fiscal Law at the University of Nairobi, said that when ruling elites are discovered to have parked cash offshore, it “is a signal to the rest of the economy that they can do the same”.

After Ms Hardy was shown the findings from the Pandora Papers, a spokesperson for the MP said: “Emma had absolutely no knowledge of this. She signed a standard tenancy agreement through a reliable agency approved by the independent organisation that administers MPs’ accommodation costs. She is shocked at what this investigation has uncovered, and believes it shows why more transparency is urgently needed.”

In December 2002 Mwai Kibaki was elected Kenya’s third president, defeating Uhuru Kenyatta. It triggered a mood change among the country’s elites as Kibaki promised an anti-corruption drive.

“The era of ‘anything goes’ is gone forever,” Kibaki said at his inauguration rally. “Corruption will now cease to be a way of life in Kenya.”

In the wake of these remarks, there was a rush of money leaving the country. There were disputed allegations that Kibaki’s predecessor as president, the deeply unpopular Daniel arap Moi, had been among those sending money abroad, in part using offshore structures and Swiss banks.

Uhuru had been Moi’s choice to succeed him and his defeat was a blow for the Kenyattas.

It was around this time in 2003 that a trust-like entity called Varies Foundation was formed in Panama, again with the assistance of the Swiss wealth advisers and Alcogal, the Pandora Papers show.

The documents show that Mama Ngina was the beneficiary, and that upon her death this secret foundation was to be run for the financial benefit of her son, Uhuru.

The Pandora Papers do not show what funds, if any, were held by Varies. According to searches of public files in Panama, the foundation is still active. However, it has not paid local regulatory taxes in the Central American country since 2014, suggesting it may now be in disuse.

A spokesperson for Mama Ngina Kenyatta did not respond to our questions.

President Kenyatta’s press office did not respond to any of our questions, including those about his offshore inheritance.

Secrecy haven

Another member of the Kenyatta family named in the Pandora Papers is Udi Gecaga, former brother-in-law to Uhuru Kenyatta. The 76-year-old today has another link to the president through his son, Jomo Gecaga, who serves as his personal secretary.

Gecaga’s fortunes had risen quickly under president Jomo Kenyatta after Lonrho, a powerful and controversial British conglomerate, with land and mining interests throughout post-colonial Africa, picked him out to be a senior executive.

Gecaga was flown to London and offered a huge sum to take the job on account of his influence within the Kenyatta family, according to a biography of Lonrho’s late chairman Tiny Rowland by journalist Tom Bower. Rowland wrote out a cheque for a five-figure sum and handed it to Gecaga: “Is this enough?… It’s for you and your family. Take care of the political problems.”

Later, Rowland occasionally said he eventually wanted Gecaga to succeed him as chairman, but within days of the death of Jomo Kenyatta in 1978, the Lonrho boss demanded his dismissal. He was eventually replaced by a close associate of Kenyatta’s successor, Moi.

Gecaga’s name appears only fleetingly in the Pandora Papers, but further investigations have shown he was no stranger to offshore investments. While he worked at Lonrho, an exotic corporate entity called Blim Securities Anstalt, formed in Liechtenstein in 1977, bought a large mansion an hour’s drive from London, which became his family home. In 1999, Blim Securities also bought an apartment near in the upmarket London neighbourhood of Knightsbridge.

An anstalt is an obscure type of trust in Liechtenstein, one of the world’s top secrecy havens.

Neither Udi Gecaga nor his son Jomo responded to our questions.

In response to questions, a spokesperson for Alcogal said it leaves clients when it suspects clients are involved in money laundering. The company added it has “a robust compliance department, comprising around 20 professionals with high-level education, that receive ongoing training in compliance according to the highest industry levels.”

The company added: “It is equally important to note that corporate providers are not legally responsible for the activities of the companies which they incorporate. While no corporate service provider or financial institution is infallible, we have always acted according to the law, and have cooperated in all respects with competent authorities.”

Having received no response from the Kenyatta family, Pandora Papers journalists searched public records in the BVI and Panama to establish whether the entities linked to the Kenyatta family were still active.

Three of the four Panamanian foundations are active and one is suspended. However, none of the four have paid the required regulatory taxes in Panama since 2014, suggesting they may have fallen into disuse.

Of the seven BVI companies we examined, one was struck off the corporate register in 2014, five were struck off between 2018 and 2021, and one remains active. A company that has been struck off the BVI register is not dissolved, and can, if required, be reinstated once outstanding regulatory fees are paid.

UPDATE October 4 2021:

On October 4, a day after our investigation was published, President Kenyatta issued a statement to say: “My attention has been drawn to comments surrounding the Pandora Papers. Whilst I will respond comprehensively on my return from my State Visit to the Americas, let me say this:

“That these reports will go a long way in enhancing the financial transparency and openness that we require in Kenya and around the globe. The movement of illicit funds, proceeds of crime and corruption thrive in an environment of secrecy and darkness.

“The Pandora Papers and subsequent follow up audits will lift that veil of secrecy and darkness for those who can not explain their assets or wealth. Thank you.”

–

* Graphics by Clement Kumalija

* Editing by Ted Jeory and Nick Mathiason

* This story was updated to include President Kenyatta’s public statement on October 4.