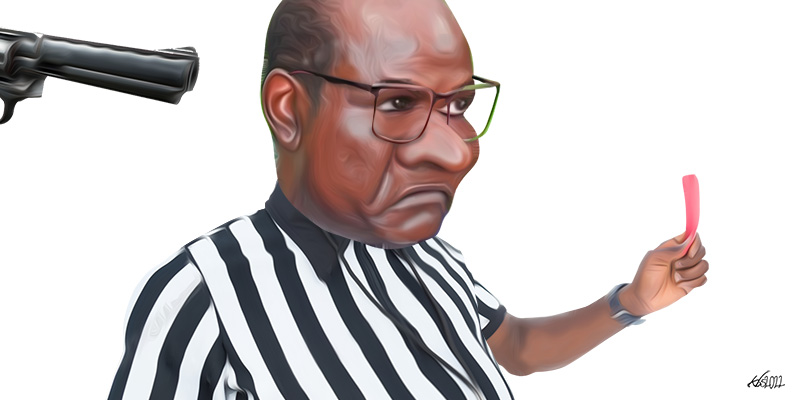

After a tallying process which ran from 9 August to 15 August 2022, Independent and Electoral Boundaries Commission (IEBC) Chairperson Wafula Chebukati declared that Hon. William Ruto had met the constitutional threshold for election as president and is therefore the President-elect. Moments before this announcement, four IEBC Commissioners—Juliana Cherera, Francis Wanderi, Irene Masit and Justus Nyangaya—issued a statement to the press disavowing the results and alleging that, due to the ‘opaque nature’ of the way the final ‘phase’ had been handled, they could not ‘take ownership’ of the results. A day later, the four Commissioners provided their reasons for disavowing the Chairperson’s declaration, key among them being that the Chairperson excluded them from the decision to declare Hon. Ruto as president-elect. Hon. Ruto’s chief competitor, Hon. Raila Odinga, has also rejected the results on similar grounds.

We have been here before of course. In 2017, there was a fallout between Chebukati and three of his Commissioners on the basis that the Commissioners did not agree with Chebukati’s leadership. As we have argued previously, the IEBC is in need of structural reform.

The events of 15th and 16th August, 2022 have stirred debate about the roles envisaged for the IEBC Chairperson and its Commissioners by the Constitution and Kenya’s election laws. Does the Chairperson’s declaration square with the law? Was he required to have a majority of the Commissioners in agreement with his declaration? Is the declaration of a winner a mere ceremonial function of the Chairperson?

The constitutional and statutory framework

Before answering these questions, it is important to look at the relevant Constitutional and statutory framework.

The IEBC is established by Article 88 of the Constitution which in sub-article (5) states that “[t]he Commission shall exercise its powers and perform its functions in accordance with this Constitution and national legislation”. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission Act (IEBC Act) was then enacted in 2011 to operationalise the entity and is the “national legislation” envisaged in the Constitution.

In relation to presidential elections, the Constitution, in Article 138(3)(c), provides that “after counting the votes in the polling stations, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission shall tally and verify the count and declare the result”.

Article 138(10) of the Constitution then provides that “[w]ithin seven days after the presidential election, the chairperson of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission shall –

- declare the result of the election; and

- deliver a written notification of the result to the Chief Justice and the incumbent President.

Section 39 of the Elections Act provides, in part:

“(1C) For purposes of a presidential election, the Commission shall –

- electronically transmit and physically deliver the tabulated results of an election for the President from a polling station to the constituency tallying centre and the national tallying centre;

- tally and verify the results received at the constituency tallying centre and the national tallying centre; and

- publish the polling result forms on an online public portal maintained by the Commission.

(1E) Where there is a discrepancy between the electronically transmitted and the physically delivered results, the Commission shall verify the results and the result which is an accurate record of the results tallied, verified, and declared at the respective polling station shall prevail.

(1H) The chairperson of the Commission shall declare the results of the election of the President in accordance with Article 138(10) of the Constitution.”

Regulation 83(2) of the Election (General) Regulations, 2012 provides that “[t]he Chairperson of the Commission shall tally and verify the results received at the national tallying centre.” Further, Regulation 87(3) reads, in part:

“Upon receipt of Form 34A from the constituency returning officers under sub-regulation (1), the Chairperson of the Commission shall –

- verify the results against Forms 34A and 34B received from the constituency returning officer at the national tallying centre;

- tally and complete Form 34C;

- announce the results for each of the presidential candidates for each County;

- sign and date the forms and make available a copy to any candidate or the national chief agent present;

- publicly declare the results of the election of the president in accordance with Articles 138(4) and 138(10) of the Constitution;

- issue a certificate to the person elected president in Form 34D set out in the Schedule; and

- deliver a written notification of the results to the Chief Justice and the incumbent president within seven days of the declaration…”

Unpacking the legal position

So, what does this all mean?

Immediately polls close, the Elections Act and its subsidiary legislation require presiding officers at each polling station to openly count ballots and declare the result. The result from each polling station within a constituency is then aggregated at constituency level and a result of this aggregation is declared by respective constituency returning officers. This process is then replicated at the national tallying centre where the Chairperson of the IEBC serves as the returning officer for the presidential elections declares the winner.

Both the IEBC Commissioners and Hon. Odinga have, in their public statements on Chebukati’s declaration of Hon. Ruto, sought to rely on a Court of Appeal decision, IEBC v Maina Kiai & 5 others [2017], suggesting in effect that the role of national returning officer does not exist and that the Chairperson is not vested with the power to declare a result without consensus or a majority decision of the Commissioners. However, this is not an accurate account of the issue before the court and its eventual holding. The issue before the court in Maina Kiai related, principally, to the ability of the Chairperson to alter results during the verification process. In question, were certain provisions of the Elections Act and the Elections (General) Regulations which provided that results declared at polling station level were ‘provisional’ and ‘subject to confirmation’, vesting in the Chairperson the ability to alter results at the national tallying centre. The Court of Appeal confirmed the constitutional and statutory position that the result declared at the polling station by presiding officers is final and cannot be altered by anyone other than an election court.

The Court was abundantly clear that Article 138(3)(c) deals with counting, tallying, verification, and declaration by the presiding officer at the polling station level and returning officers at each subsequent level, and not just the Chairperson at the Commission level. In other words, in discharging its mandate under Article 138(3)(c), the IEBC, which is a body corporate, acts through its representatives who are the presiding officers and returning officers. In undertaking the verification exercise at subsequent levels after the polling station, the respective officers are simply required to confirm whether the tally at each level conforms to the declaration which was made by the presiding officer at the polling station and to declare this result. Consequently, the constituency returning officer and the national returning officer (who is the IEBC Chairperson) cannot alter the results in any way when making these declarations. This is the mischief that the Maina Kiai case addressed, and in doing so, it invalidated certain sections of the Elections Act and the Elections (General) Regulations which suggested that results at the polling station level were provisional and subject to alteration or confirmation by the Chairperson. By doing this, the Court of Appeal aligned these laws with the Constitutional position.

Notably, Regulation 83(2) and 87(3) of the Election (General) Regulations which we quoted above, and which empower the Chairperson to tally, verify, and declare the results received at the national tallying centre, were not the subject of the Maina Kiai decision, and as such were not invalidated. However, the Court of Appeal clarified that in tallying and verifying results, the Chairperson is bound by the results declared at each polling station which are final. Indeed, in the Maina Kiai case, the Court of Appeal recognised the special role of the Chairman and stated:

“It cannot be denied that the Chairperson of the appellant has a significant constitutional role under Sub-Article (10) of Article 138 as the authority with the ultimate mandate of making the declaration that brings to finality the presidential election process. Of course, before he makes that declaration his role is to accurately tally all the results exactly as received from the 290 returning officers country-wide, without adding, subtracting, multiplying, or dividing any number contained in the two forms from the constituency tallying centre. If any verification or confirmation is anticipated, it has to relate only to confirmation and verification that the candidate to be declared elected president has met the threshold set under Article 138(4), by receiving more than half of all the votes cast in that election; and at least twenty- five per cent of the votes cast in each of more than half of the counties.”

So, if anything, the Maina Kiai decision reinforced the role of the Chairperson as the national returning officer of the presidential election, contrary to the statement issued by the four Commissioners on 16th August which alleged that such a role does not exist. Further, the Supreme Court of Kenya in the Joho v Shahbal case made it clear that a declaration takes place at each stage of tallying, implying that the verification and declaration process is not the preserve of the Commissioners. It is done by the respective presiding and returning officers at each stage. The High Court, at an earlier stage of the same case, had confirmed that declarations are made through formal instruments, which in the electoral context, are the certificates issued by the respective returning officers. To render even more clarity, in its majority decision in Petition 1 of 2017 Raila Odinga v IEBC & 2 others [2017], the Supreme Court stated that ‘[t]he duty to verify in Article 138 is squarely placed upon the IEBC (the 1st respondent herein). This duty runs all the way from the polling station to the constituency level and finally, to the National Tallying Centre. There is no disjuncture in the performance of the duty to verify. It is exercised by the various agents or officers of the 1st respondent, that is to say, the presiding officer at a polling station, the returning officer at the constituency level and the Chair at the National Tallying Centre’.

With both the Constitutional and statutory framework and this recent jurisprudence in mind, it is apparent that when it comes to the declaration of results, the Chairperson is not merely performing a ceremonial role on behalf of the Commission but has a singular responsibility to discharge a constitutional duty to declare a president-elect after verifying the results. Once the presiding officers and constituency returning officers discharge their mandate, they hand the baton to the Chairperson for him to also do so. He therefore does not discharge his mandate in isolation or in an arbitrary manner; his role is hinged upon other IEBC officers at various levels dispensing with their mandate. Like the rest, he may not deviate from the declaration made at the polling station. In that way, he acts as a representative or an agent of the entire IEBC in discharging his mandate. This position is aligned with the Elections (General) Regulations and the Supreme Court’s decision in Raila v IEBC which provide that the Chairperson, as the IEBC’s agent, can verify the results and make a declaration. For these reasons, Chebukati’s declaration, we argue, is in accordance with the law.

In public debates following Chebukati’s declaration of a president-elect, there has been an argument in some quarters that the Second Schedule to the IEBC Act and in particular paragraph 7 which reads “[u]nless a unanimous decision is reached, a decision on any matter before the Commission shall be by a majority of the members present and voting”, suggests that the dissension of the majority of the Commissioners on grounds of ‘opaqueness’ meant that Chebukati did not have the authority to make the declaration. Azimio La Umoja Coalition Party presidential candidate Hon. Odinga forms part of the individuals advancing this argument when rejecting the legality of Chebukati’s declaration of Hon. Ruto as president-elect. The Second Schedule is made pursuant to Section 8 of the IEBC Act which provides that “[t]he conduct and regulation of the business and affairs of the Commission shall be provided for in the Second Schedule but subject thereto, the Commission may regulate its own procedure.” The Second Schedule is akin to the provisions of the Articles of Association of a company which deals with how board meetings are conducted. It deals with matters such as how meetings are called, how quorum is formed and other such administrative matters. Note that paragraph 7 is specifically limited to matters ‘before the Commission’. As set out in the preceding paragraph, the declaration of a president-elect is a matter for the Chairperson and not a matter ‘before the Commission’.

In any case, those arguing the contrary have two further obstacles to overcome. Firstly, how do they reconcile their position with the clear constitutional injunctions imposed on the Chairperson by Article 138(10) requiring the Chairperson to declare the results of the Presidential election within 7 days after the Presidential election. What did they expect Chebukati to do? Continue negotiating with the dissenting Commissioners and allow the 7 days to expire? If so, does this mean Chebukati should place the views of his Commissioners above the Constitutional requirement in Article 138(10) even though, at each stage, representative officers of the IEBC verified, declared, and made the results public? The reason for Article 138(10), in our view, is obvious. In matters relating to the transfer of Presidential power, certainty of process and timing is critical. One cannot leave matters in abeyance and risk a constitutional crisis with an incumbent holding on or causing the delay in the assumption of office by his successor. This would be a recipe for a constitutional crisis with a myriad of implications for Kenyans, especially in relation to their safety and security.

Ultimately, Chebukati’s decision is not final: there is the Supreme Court to which those disgruntled by his declaration can appeal. Although not final, finality in the process of tallying and subsequent declaration is critical. To take such a dramatic step of disavowing the results at a moment when the country was on edge, we would have thought that the four Commissioners would present some compelling evidence pointing to miscalculation on the part of Chebukati in the tabulation of the statutory forms 34A, 34B and 34C. Kenyans have not yet been presented with any such compelling evidence.

Turning to the absence of compelling evidence, one would expect a detailed explanation from the four Commissioners. In their statement following their initial announcement, they disclosed four reasons for their dissent. The first was in relation to the aggregation of the tally surpassing 100% by a margin of 0.01%. A simple calculation reveals that the error may be attributable to the Chairperson rounding the figures upward for purposes of the declaration.

Their second reason was that the Chairperson, in his declaration, did not indicate the total number of registered voters, the total number of votes cast or the number of rejected votes. The declaration of results form available on the IEBC’s website indicates that this is not true as the declaration form does contain all this information.

In their third reason, the Commissioners relied on the Maina Kiai decision to allege that the “Commission has to process the results before they are declared and announced by the Chairperson”. As we have set out above, the Court of Appeal in Maina Kiai indicated that the IEBC, as a body corporate, acts through its officers, specifically the presiding and returning officers who fulfil the IEBC’s obligation under Article 138(3)(c) of the Constitution on the institution’s behalf. Given the results were, at each stage, tallied, verified, and declared by presiding and returning officers including the Chairperson, it is not immediately clear what further ‘processing’ the Commissioners wanted to subject the results to, especially when the Court of Appeal explicitly held that once declared at constituency level, a result is final. The law certainly does not disclose a role for these Commissioners to ‘process’ these results any further. It only envisions a role for the Chair to verify the results and make a declaration. The reliance on Maina Kiai is also misleading in the sense that it implies the Chairperson acted in isolation and in an arbitrary manner, yet he was clearly bound to the results declared by other officers at the polling station level which were publicly available.

Their final reason was that the Chairperson made his declaration before several constituencies had their results declared. The Elections Act provides that the Chairperson may only do so if “in the opinion of the Commission the results that have not been received will not make a difference with regards to the winner”. However, the challenge with this reason is that the Chairperson did not indicate that his declaration was made on the basis that the results were not complete and that the remainder would not make a difference. Perhaps at the Supreme Court, this ground will be elaborated on further.

In light of the above, on the limited point of whether Chebukati had the power to make the declaration that he did on 15th August, 2022, we are of the view that he did and that in doing so he has fulfilled the obligations required of his office in accordance with the principles of the Constitution and the relevant election laws.