A joint investigation by IrpiMedia and The Elephant

Soon after Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto secured a controversial second term in November 2017, investigations begun into the procurement and financing arrangements surrounding the Arror and Kimwarer dams in the Rift Valley county of Elgeyo Marakwet.

The dams had been commissioned years earlier, and billions had been paid out but there was nothing on the ground to show for either dam. The Kimwarer project has since been cancelled, the Arror one scaled down, and eight defendants today face charges of conspiring to defraud the government of nearly Sh60 billion. However, there have been claims that the investigations and prosecutions are politically motivated and aimed at weakening Deputy President William Ruto who is running to becoming Kenya’s fifth president. Just this week, during the presidential debate, Ruto essentially said the dams were casualties of the 2018 fallout with his boss. This has been many times denied by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

The two cases dealing with the dams at the Anti-Corruption Court in Milimani, Nairobi, focus on alleged irregularities in the tendering and contracting of the dams as well as alleged illegal payments made to two Italian companies. The crux of the ODPP’s case is that officials of Kerio Valley Development Authority and the national government colluded to grant CMC di Ravenna and its joint venture partner, Itinera S.P.A, a contract for the construction of the two dams for which they had not won the tender and that differed fundamentally from the terms advertised in December 2014, which called for proposals for the “funding, design, build and transfer” of the dams. The eight Kenyan officials in case No. 20 of 2019 and the 18 Italian companies and individuals in case No. 21 of 2019, are accused of executing a sleight of hand, initially pretending that the contractors would mobilize money from the Italian government to build the dams and then switching it to a commercial loan with the government as the borrower. Furthermore, instead of the borrowed money being deposited into the Consolidated Fund as the constitution prescribes, on the contrary, it was sent directly to the contractor. In the ODPP’s view, this is where the fraud arose.

The initial contracting model selected was Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Financing where the contractor also arranges financing for the project through tie-ups with financing institutions. They can be useful when contractors have better access to low-cost financing, including state-provided export-import financing. However, the Parliamentary Service Commission has noted that these contracts are vulnerable to abuse and in 2019 parliament suspended 20 dam projects, including Arror and Kimwarer, saying “Kenyans [were] not getting value for money in this model”.

According to the ODPP, the tendering process for the two dams was riddled with irregularities. In an affidavit sworn in February 2020 on behalf of the DPP, Police Constable Thomas Tanui states that, unlike the Arror dam, the Kimwarer project had not been approved by the Cabinet, as required by the 2013 Public Private Partnership Act (PPA). Further, in the course of the process, the tender documents for CMC di Ravenna were illegally altered at least twice to switch CMC’s joint venture partners from South Africa’s AECOM to a company only known as MWH, and then again to Itinera S.P.A. And while it was Italy-based CMC di Ravenna that made the bid, the tender was awarded to South Africa-based CMC di Ravenna, a different legal entity with whom KVDA signed Memoranda of Understanding regarding the two dams in December 2015 and February 2016 that were meant to end with the signing of concessional contracts within 8 months.

However, the MOUs expired without the concessional contracts being signed and instead, on 5 April 2017, the KVDA signed commercial contracts for the construction of both dams with the Italian CMC di Ravenna and its joint venture partner Itinera S.P.A. for a total combined amount of US$501.8 million, including 10 per cent contingencies that had not been negotiated for under the concessional agreements.

In his affidavit, PC Tanui avers that the dam projects were conceived as concessionary projects under the PPA but were surreptitiously converted into a commercial instead of a concessional contract. However, what the ODPP means by “concessional contract” and how that differs from a commercial contract is not clear. There’s no mention of a “concessional contract” in the PPA which defines a concession as “a contractual licence . . . entitling a person who is granted the licence to make use of the specified infrastructure or undertake a project and to charge user fees, receive availability payments or both”. While the law allows government agencies to “enter into a project agreement with any qualified private party for the financing, construction, operation, equipping or maintenance” of infrastructure, none of the 15 types of public private partnership arrangements it lists in its second schedule seem to fit what KVDA had initially advertised.

However, perhaps what the ODPP refers to as a “concessional contract” is a reference to the way the project was to be funded. According to press reports and Richard Malebe’s petition, the initial charges alleged that the national government and KVDA officials as well as the Italian companies conspired to “entered into a commercial loan facility agreement disguising it as a government-to-government loan guaranteed by the Italian Government . . . ‘while knowing the tender document contained in the request for proposals for the development of the dams project was a concessional agreement where the intended concessionaire was to be the borrower and financier and not the Government of Kenya’”. In essence, by substituting the commercial contract for the concessional one, rather than an arrangement where Government only paid once the dams were delivered, with the contractor and financiers assuming all the risk, it was the public that was left holding the baby when things went wrong. If anything, the Kenyan public paid to insure the banks against government default, which insurance the ODPP says was illegally single-sourced.

A Treasury press statement dated 28 February 2019, signed by one of the accused, former Cabinet Secretary Henry Rotich claims that the financing agreement for the two dams was “government-to-government” with the Italian government—represented by the 100 per cent owned Servizi Assicurativi Del Commercio Estero (SACE)—providing “insurance cover and financial support” amounting to close to 88 per cent of the total loan amount, with a consortium of four banks led by Intesa Sanpaolo said to provide the rest. The statement details “the Conditions Precedent”, which were payments apparently required before funds could be released to the government and the contractor. These include €7.83 million (Sh951 million) in fees and commissions and €94.2 million (Sh11.4 billion) in credit insurance to cover lenders for both dams. In addition, another US$75.2 million (Sh9 billion), or 15 per cent of the total contract sum for both dams was paid out to the contractor.

The Kenyan public paid to insure the banks against government default, which insurance the ODPP says was illegally single-sourced.

The Treasury claims these fees and advances were provided for and paid from the loan from SACE and the banks, not Exchequer funds. This aligns with a November 2019 note by SACE to the Italian foreign ministry which states that the agreement required the “payment of the sums due by the Contracting Authority to the CMC-Itinera joint venture through direct disbursement by the lenders on a current account of the contractor opened outside the State of Kenya” —a violation of the Kenyan constitution which requires all sums borrowed by the government to be deposited in the Consolidated Fund. However, according to both CMC-Itinera and a confidential analysis by the ODPP seen by The Elephant, the advance payment was for a total of €66.6 million (Sh8.09 billion), a discrepancy of nearly Sh1 billion. (It should be noted that the National Treasury appears to have entered into a facility contract with lenders in Euros, and payments appear to have been made in the same currency, even though the commercial contracts were in US dollars, which exposed taxpayers to losses through changes in the exchange rates. In this article, we have used the current exchange rates to reflect the amounts in Kenya Shillings.)

Further, according to business journalist Jaindi Kisero, SACE does not appear in the external debt register which raises doubts as to whether they were indeed the main lender. Also, the November 2019 note by SACE to the Italian foreign ministry says the insurance guarantee was “in favor of the Lenders for the entire amount financed”, which seems to say that all the money came from the banks. The ODPP analysis says that while the agreements make it clear that SACE was one of the financiers, the agency did not act as a party to them. It argues that the insurance premium was fraudulent because if the funds came from SACE, as the agreements suggest, it would have been a government-to-government loan which would require no insurance. It concludes that “payments made by GoK were made with the intention to siphon money from the country in the disguise of advance payment, insurance premium and commitment fees”.

Deputy President Ruto has claimed that only Sh7 billion was in question and that the government had a bank guarantee that protected every penny. The Treasury statement seems to back him up, at least as far as the guarantee is concerned, claiming the advance payment was backed by “a bank/insurance guarantee” which would be called “if the contractor is unable to deliver the service to the Government or runs bankrupt”. And in February 2022 Regional Development Principal Secretary Belio Kipsang told Parliament that Heritage Insurance and Standard Chartered Bank had respectively issued insurance guarantees for the advances paid to the CMC Ravenna-Itinera joint venture for Arror (Sh4.1 billion) and Kimwarer (Sh3.6 billion). He said the government had already recalled the Arror guarantee and was planning to do the same regarding Kimwarer, whose guarantee expires in June 2023. However, it is again unclear from his statement what currency the guarantees are in: dollars, euros or shillings. If in shillings, then it seems that up to Sh1.3 billion may not be covered.

The ODPP analysis says that while the agreements make it clear that SACE was one of the financiers, the agency did not act as a party to them.

It is unclear exactly how much Kenya stands to lose given the discrepancies in the currencies used. In total, according to the ODPP, €168.5 million (Sh20.5 billion) was paid between 4 May 2017 and 7 November 2018 to cover the insurance premium, various fees as well as the advance payments. The statement from the Treasury, as noted above, puts this figure at €102 million and US$75.2 million for a total of Sh23.5 billion at current rates. In addition, the external debt register lists Kenyans as being on the hook for the entire loan amount of €578.4 million (Sh70.3 billion) which stands to be repaid until November 2035. Yet it does not seem that any further disbursements have been made by the banks to the companies beyond the insurance premium, fees and commissions and the advance payment. Why the full loan amount would be reflected as drawn down in the debt register is a mystery. It is also noteworthy that Kenya has refused or failed to make any repayments on the moneys already disbursed.

The cases at the Milimani Anticorruption Court provide few concrete answers. There are currently two cases, consolidated from the initial four—two cases for each dam dealing separately with charges of financial and procedural irregularities. Each of the four initial cases had numerous defendants including directors of companies based in Italy who refused to come to Kenya to take plea, occasioning long delays. Eventually, all the cases were consolidated into two, with Case 20 of 2019 having 8 accused persons based in Kenya, and Case 21 of 2019 dealing with the alleged crimes of 18 Italian individuals and companies. This arrangement has allowed the Kenyan cases to proceed with the first witness out of 57 taking the stand in November last year.

One strange thing about the cases filed by the ODPP is that while they allege a conspiracy to defraud the government through the commercial agreements, there is little indication of the other side of that coin: how did the individuals involved benefit from the scheme? No one is charged with paying or receiving a bribe and there has been little evidence produced so far to warrant the many press allegations of corruption and kickbacks. According to a report in the East African Standard, Sh450 million was “wired by the Treasury to Italian firm CMC di Ravenna . . . was sent to an account in London then Dubai and later to Nairobi”. One of the report’s writers, Roselyne Obala, would later add that the same Sh450 million was part of a larger payment of over Sh600 million and that it was paid to an account in Barclays Bank in Nairobi. However, none of this is in the charges preferred at the Anti-Corruption Court. Further, it is unclear whether “over KSh600 million” refers to the much larger advance payments which, in any case, was (illegally) transferred directly by the banks in London to the companies. Further, the absence of prosecutions within Italy, which has a law criminalizing Italian companies paying bribes to public officials abroad in return for contracts, suggests that there is no evidence that a bribe was paid in this case.

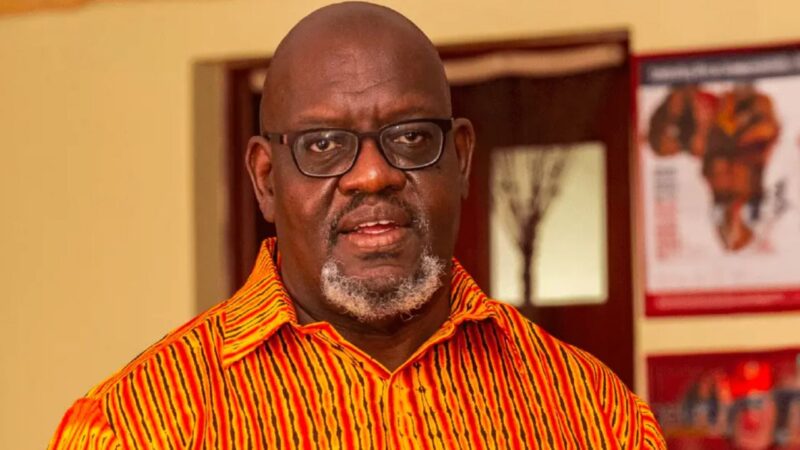

There have been allegations raised that the prosecution of the dam cases was politicised, targeting allies of Deputy President William Ruto. In October last year, Rotich instituted a petition at the Milimani High Courts questioning why the DPP left out key personalities involved in the tendering process such as the former Attorney General Githu Muigai, solicitor general Njee Muturi and former Environment CS Judi Wakhungu. Rotich has also argued that he was not responsible for procurement of the tenders and was not the accounting officer at Treasury. “It is absurd that the respondents chose to charge me while the Attorney General is not charged in this respect. This is an indication of selective prosecution that cannot stand the test of objectivity and fair administration of action,” he argued in the petition. Others have pointed to the dropping of charges against members of the KVDA Tender Committee as well as some of Rotich’s co-accused, former Treasury PS Kamau Thugge and Dr Susan Koech, a former PS in the Environment Ministry, as proof of malicious prosecution.

It is also noteworthy that Kenya has refused or failed to make any repayments on the moneys already disbursed.

Regarding the latter accusation, it is notable that many of the former accused have actually become witnesses so it may just be a case of the DPP using the small fry to net the “big fish”. However, when it comes to why the former AG, the solicitor-general, and the various ministers who oversaw KVDA between 2014 and 2019 are not in the dock, the answers are not so convincing.

A bigger source of discontent is the lack of similar prosecutions over similar projects. For example, the contract over the Itare Dam in Nakuru, also in the Rift Valley, features the same set of characters—SACE, CMC di Ravenna, Intesa San Paolo, BNP Paribas—and was the first dam awarded to the Italians in 2014. After advance payments of Sh4.3 billion were paid out, the project appears to have collapsed. As Nakuru Senator Susan Kihika noted in February 2019, “It . . . seems as if there is no equal treatment of all the projects across the country.”

In 2013, CMC had signed a consultancy contract with Stansha Limited, owned by Stanley Muthama, the MP for Lamu West, in which Stansha pledged to help CMC in its bid for tenders for the construction of Itare Dam, which is under the Rift Valley Water Services Board, and Ruiru II Dam under the Athi Water Service Board, for a fee of 3 per cent of the contract value. For Itare, it came to Sh330 million. According to the ODPP analysis, on 25 November 2015, a Stanley Muthama identified as “Staff CMC Kenya office” participated in a high-level “clarification meeting” with KVDA officials regarding the tender for the Arror dam, one of the decisive meetings for the award of the contract. Among those at the meeting were Paolo Porcelli and Gianni Ponta, two CMC officials the ODPP has charged, among others, for having “conspired to unlawfully have the services of CMC di Ravenna-ITINERA JV procured by KVDA for the development of Arror and Kimwarer multipurpose dams”. There is however no Stanley Muthama being prosecuted by the ODPP in the Kenyan case and no suggestion of any wrongdoing with regard to the contracts.

There, however, seems to be a pattern emerging where CMC di Ravenna—which has been in economic turmoil for four years; in 2018 it owed creditors €1.5 billion euros—receives advance payments for projects it does not thereafter complete. In Nepal, a US$550 million contract for the construction of a hydroelectric plant was terminated in 2019 and the company ordered by an Italian court to return €15 million to a bank in Nepal that had financed the project. CMC had not warned the Nepalese bank of its financial problems and had not even begun the work.

In Kenya, though, the two Italian firms have also claimed the cases were politicised and lacked grounds. In December 2020, they filed a suit at the International Court of Arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce claiming they were victims of power politics between President Uhuru and his deputy William Ruto. They alleged that the cancellation of the tender was a ploy to weaken Deputy President Ruto’s 2022 presidential aspirations and are demanding US$115 million (KSh13.7 billion) in compensation for the cancellation of the contracts.

A bigger source of discontent is the lack of similar prosecutions over similar projects.

“It seems hardly coincidental that the highest ranking official to be investigated and charged in the criminal proceeding is Kenya’s Treasury CS Mr Henry Rotich, an ally of Mr Ruto,” stated the court document as reported in Business Daily. They claim that allegations of impropriety did not surface until two years after the contracts were signed and that KVDA had admitted that the projects had been politicised with an intention of terminating them.

In notes sent to the Italian Foreign Ministry, the joint venture complains of “delays in the payment of fees [by Kenya] to the Agent Bank with the risk of blocking future disbursements”. The companies blame the failure of the project to get off the ground on the failure by KVDA to deliver the necessary land, a claim repeated by Deputy President Ruto during the presidential debate in July. They also claim that import permit exemptions had not yet been issued.

President Kenyatta has also reportedly tasked AG Paul Kihara and Head of Public Service Joseph Kinyua to negotiate with the joint venture to seek an amicable settlement although it is curious that Kenya would seek to pay off the very companies it accuses of conspiring to defraud it. The country has, however, trodden this route before. In 2014, President Kenyatta ordered payment of Sh1.4 billion to briefcase companies for termination of contracts to supply telecommunication equipment and bandwidth spectrum, part of the Anglo Leasing scam where billions were paid to fictitious companies for security-related contracts.

Further, in May last year, SACE wrote to the AG, the Treasury and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs saying that Kenya could get a partial refund of its insurance premium but only if it committed to paying off the banks on whose behalf the country had taken out the policy. And the letter included a not-so-subtle hint that Kenya’s relationship with Italy was on the line.

They alleged that the cancellation of the tender was a ploy to weaken Deputy President Ruto’s 2022 presidential aspirations.

In brief, it seems clear that there were serious irregularities during the tendering and contracting for the two dams. KVDA tendered the projects under the PPA for a concessional arrangement but awarded a commercial contract under the Public Procurement and Disposal Act to a legally different entity from that which had won the tender without beginning the process afresh. Further, the arrangements to transfer money directly from commercial banks to the contractor seem clearly illegal and the shift from a concessional arrangement to a commercial one probably means Kenyans ended up paying more—including for unnecessary insurance. However, no money appears to have been paid out directly from the Exchequer, although the fees, commissions and advance payments have accrued a debt of up to Sh23.5 billion (at current exchange rates), less than a third of which may be covered by bank/insurance guarantees. Assuming the debt register is mistaken when it lists the entire loan amount, and that the guarantees by Standard Chartered Bank and Heritage Insurance are eventually honoured, Kenyans would still be, when we eventually get round to paying it, out of pocket by around Sh13.5 billion, the sum of the insurance premium (part of which we may get back), the various fees and commissions, and the exchange rate costs. As noted, no one has been accused of actually pocketing bribes. It also does not seem like either Kenya or the banks are pursuing a refund of the money paid to the joint venture in the Italian courts.

The biggest obstacle to a clearer understanding of what is happening with regard to the Arror and Kimwarer dams is the political whirlwind around it. Adding to the confusion is the language employed—terms like scam and kickbacks—suggesting that the officials involved pocketed bribes, whereas they are not actually accused of any of that. Further, journalists have tended to report the story much like the proverbial blind men of Hindustan—each accurately describing a part of the elephant’s anatomy, but not able to grasp the entire animal., It is to be expected that, even after the general election, the controversy surrounding the Arror and Kimwarer dams will continue to generate more political heat while shedding very little light.