Do we move to change, or do we move to stay the same?

That seems to depend on who we were, to begin with. In most cases, it seems we move in an attempt to become even more of whatever we think we are.

A good Kenyan friend of mine once (deliberately) caused great offense in a Nairobi nightspot encounter with a group of Ugandans he came across seated at a table. There were six or seven of them, all clearly not just from the same country, but from the same part of the country.

“It always amazes me,” he said looking over their Western Uganda features, “how people will travel separately for thousands of miles only to meet up so as to recreate their villages.

He moved along quickly.

“Most African Migration Remains Intraregional” is a headline on the Africa Centre for Strategic Studies website:

Most African migration remains on the continent, continuing a long-established pattern. Around 21 million documented Africans live in another African country, a figure that is likely an undercount given that many African countries do not track migration. Urban areas in Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt are the main destinations for this inter-African migration, reflecting the relative economic dynamism of these locales.

Among African migrants who have moved off the continent, some 11 million live in Europe, almost 5 million in the Middle East, and more than 3 million in America.

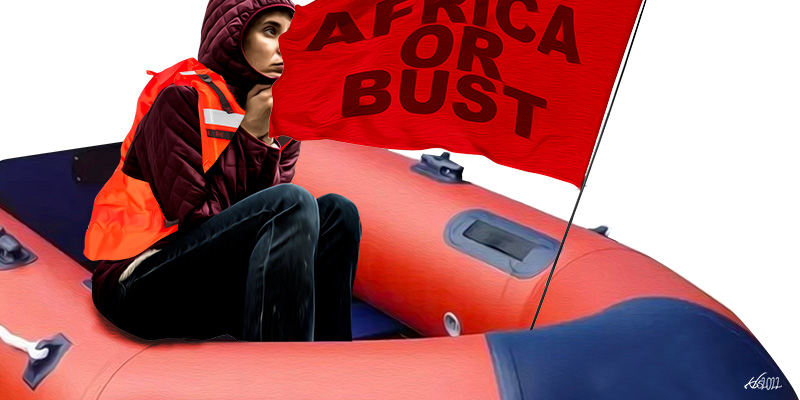

More Africans may be on the move now than at any time since the end of enslavement, or perhaps the two large European wars. Even within the African continent itself. They navigate hostilities in the cause of movement—war, poverty and environmental collapse.

The last 500 years have seen the greatest expression of the idea of migration for the purpose of staying the same (or shall we say, becoming even more of what one is). The world has been transformed by the movement of European peoples, who have left a very visible cultural-linguistic stamp on virtually all corners of the earth. It is rarely properly understood as a form of migration.

It took place in three forms. The first was a search for riches by late feudal Western European states, in a bid to solve their huge public debts, and also enrich the nobility. This was the era of state-sponsored piracy and wars of aggression for plunder against indigenous peoples. The second form was the migration of indentured Europeans to newly conquered colonial spaces. The third was the arrival of refugees fleeing persecution borne of feudal and industrial poverty, which often took religious overtones.

Certainly, new spaces often create new opportunities, but only if the migrants concerned are allowed to explore the fullness of their humanity and creativity. The historical record shows that some humans have done this at the expense of other humans.

A key story of the world today seems to be the story of how those that gained from the mass and civilizational migrations of Western Europe outwards remain determined to keep the world organised in a way that enables them to hold on to those gains at the expense of the places to which they have migrated.

We can understand the invention and development of the modern passport—or at least its modern application—as an earlier expression of that. Originally, passports were akin to visas, issued by authorities at a traveler’s intended destination as permission to move through the territory. However, as described by Giulia Pines in National Geographic, established in 1920 by the League of Nations, “a Western-centric organization trying to get a handle on a post-war world”, the current passport regime “was almost destined to be an object of freedom for the advantaged, and a burden for others”. Today the dominant immigration models (certainly from Europe) seem based around the idea of a fortress designed to keep people out, while allowing those keeping the people out to go into other places at will, and with privilege, to take out what they want.

Certainly, new spaces often create new opportunities, but only if the migrants concerned are allowed to explore the fullness of their humanity and creativity.

For me, the greatest contemporary expression of “migration as continuity” has to be the Five Eyes partnership. This was an information-sharing project based on a series of satellites owned by the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Its original name was “Echelon”, and it has grown to function as a space-based listening system, spying on telecommunications on a global scale – basically, space-based phone tapping.

All the countries concerned are the direct products of the global migration and settlement of specifically ethnic English Europeans throughout the so-called New World, plus their country of origin. The method of their settlement are now well known: genocide and all that this implies. The Five Eyes project represents their banding together to protect the gains of their global ethnic settlement project.

In the United States, many families that have become prominent in public life have a history rooted, at least in part, in the stories of immigrants. The Kennedys, who produced first an Ambassador to the United Kingdom, and then through his sons and grandsons, a president, an attorney general, and a few senators, made their fortune as part of a gang of Irish immigrants to America involved in the smuggling of illicit alcohol in the period when the alcohol trade was illegal in the United States.

Recent United States president Donald Trump is descended from a German grandfather who, having arrived in 1880s America as a teenage barber, went on to make money as a land forger, casino operator and brothel keeper. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States was the paternal grandson of a trader named Warren, a descendant of Dutch settlers who made his fortune smuggling opium into China in the 1890s.

While it is true that the entire story of how Europeans came to be settled in all the Americas is technically a story of criminality, whether referred to as such or not, the essential point here is that many of the ancestors of these now prominent Americans would not have passed the very same visa application requirements that they impose on present-day applicants.

The purpose of migrations then was the same as it is now: not simply to move from one point to another, but also from one type of social status to another. It was about finding wealth, and through that, buying a respectability that had not been accessible in the country of origin. So, the point of migration was in a sense, not to migrate, but to change one’s social standing.

And once that new situation has been established, then all that is left is to build a defensive ring around that new status. So, previously criminal American families use the proceeds of their crime to build large mansions, and fill the rooms with antiques and heirlooms, and seek the respectability (not to mention business opportunities) of public office.

Many of the ancestors of these now prominent Americans would not have passed the very same visa application requirements that they put to present-day applicants.

European countries that became rich through the plunder of what they now call the “developing world”, build immigration measures designed to keep brown people out while allowing the money keep coming in. They build large cities, monuments and museums, and also rewrote their histories just as the formerly criminal families have done.

Thus the powers that created a world built on migration cannot be taken seriously when they complain about present-day migration.

Migration is as much about the “here” you started from, as it about the “there” you are headed to. It is not about assimilating difference; it is about trying to keep the “here” unchanged, and then to re-allocate ourselves a new place in that old sameness. This is why we go “there”.

This may explain the “old-new” names so common to the mass European migration experience. They carry the names of their origins, and impose them on the new places. Sometimes, they add the word “New” before the old name, and use migrant-settler phrases like “the old country”, “back east”. They then seek to choose a new place to occupy in the old world they seek to recreate, that they could not occupy in the old world itself. But as long as the native still exists, then the settler remains a migrant. And the settler state remains a migrant project.

To recreate the old world, while creating a new place for themselves in it, , such migrants also strive to make the spaces adapt to this new understanding of their presence that they now seek to make real.

I once witness a most ridiculous fight between three Ugandan immigrants in the UK. It took place on the landing of the social housing apartment of two of them, man and wife, against the third, until that moment, their intended house guest. As his contribution to their household, the guest had offered to bring a small refrigerator he owned. However, when the two men went to collect the fridge in a small hired van, the driver explained that traffic laws did not permit both to ride up front with him – one would have to ride in the back with the fridge. The fridge owner, knowing the route better, was nominated to sit up front, to which his friend took great and immediate exception; he certainly had not migrated to London to be consigned to the back of a van like a piece of cargo. After making his way home via public means, and discussing his humiliation with his good wife, the arrangement was called off – occasioning a bitter confrontation with the bewildered would-be guest.

There must have been so many understandings of the meaning of their migration to Britain, but like the Europeans of the New World, the Ugandans had settled on replicating the worst of what they were running from in an attempt to become what they were never going to be allowed to be back home.

A good case in point is the ethnic Irish communities in Boston and New York, whose new-found whiteness—having escaped desperate poverty, oppression and famine under British colonial rule on what were often referred to as “coffin ships” —saw them create some of the most racist and brutal police forces on the East Coast. They did not just migrate physically; they did so socially and economically as well.

It starts even with naming.

The word “migrant” seems to belong more to certain races than to others, although that also changes. When non-white, normally poor people are on the move, they can get labeled all sorts of things: refugees, economic migrants, immigrants, illegals, encroachments, wetbacks and the like.

With white-skinned people, the language was often different. Top of the linguistic league is the word “expatriate”, to refer to any number of European-origin people moving to, or through, or settling in, especially Africa.

According to news reports, some seven million Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion were absorbed by their neighboring European countries, most of which are members of the European Union. Another 8 million remain displaced within the war-torn country.

This is an outcome of which the Europeans are proud. They have even emphasized how the racial and cultural similarities between themselves and the Ukrainian refugees have made the process easier, if not a little obligatory.

This sparked off a storm of commentary in which comparisons were made with the troubles earlier sets of refugees (especially from the Middle East and Afghanistan) faced as the fled their own wars and tried to enter Western Europe.

And the greatest irony is that the worst treatment they received en-route was often in the countries of Eastern Europe.

Many European media houses were most explicit in expressing their shock that a war was taking place in Europe (they thought they were now beyond such things), and in supporting the position that the “white Christian” refugees from Ukraine should be welcomed with open arms, unlike the Afghans, Iraqis and Syrians before them.

Human migration was not always like this.

Pythagoras (570-495 BC), the scholar from Ancient Greece, is far less well remembered as a migrant and yet his development as a thinker is attributable to the 22 or so years he spent as a student and researcher in Ancient Egypt. The same applies to Plato, who spent13 years in Egypt.

There is not that much evidence to suggest that Pythagoras failed to explain where he got all his learning from. If anything, he seems to have been quite open in his own writing about his experiences, first as an apprentice and later a fellow scholar in the Egyptian knowledge systems. The racial make-up of Ancient Egypt, and its implications, was far from becoming the political battleground it is today.

Top of the linguistic league is the word “expatriate” to refer to any number of European-origin people moving to, or through, or settling in, especially Africa.

Classic migration was about fitting in. Colonial migration demands that the new space adapt to accommodate the migrant. The idea of migrants and modern migration needs to be looked at again from its proper wider 500-year perspective. People of European descent, with their record of having scattered and forcibly imposed themselves all over the world, should be the last people to express anxieties about immigrants and migration.

With climate change, pandemic cycles, and the economic collapse of the west in full swing, we should also focus on the future of migration. As was with the case for Europeans some two to three hundred years ago, life in Europe is becoming rapidly unlivable for the ordinary European. The combination of the health crisis, the energy crisis, the overall financial crisis and now a stubborn war, suggests that we may be on the threshold of a new wave of migration of poor Europeans, as they seek cheaper places to live.

The advantages to them are many. Large areas of the south of the planet are dominated physically, financially and culturally, by some level of Western values, certainly at a structural level. Just think how many countries in the world use the Greco-Latin origin word “police” to describe law enforcement. These southern spaces have already been sufficiently Westernized to enable a Westerner to live in them without too much of a cultural adjustment on their part. The Westerners are coming back.

–

This article is part of a series on migration and displacement in and from Africa, co-produced by the Elephant and the Heinrich Boll Foundation’s African Migration Hub, which is housed at its new Horn of Africa Office in Nairobi.