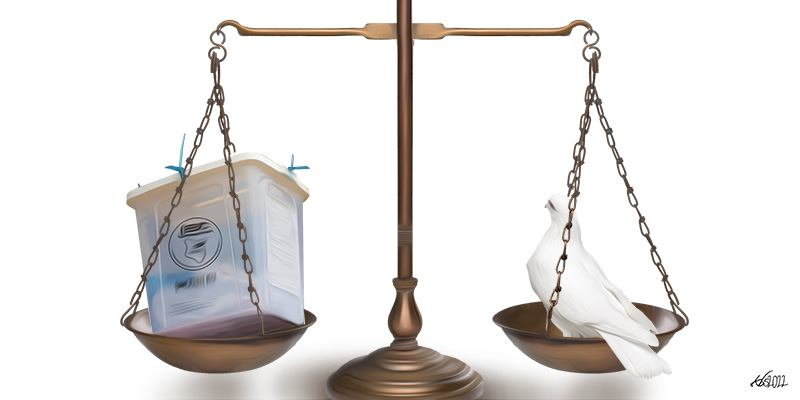

On the 9th of August, Kenyans will once again queue to vote in the seventh general election since the introduction of multi-party politics in 1992. The elections will also mark the third time in Kenya’s multi-party history that power will be transferred from one ruler to another through the ballot. In recent months, the question for many observers has been whether the elections and the transition process will be peaceful or violent.

Given Kenya’s recent history of political violence, this is, actually, a genuine and legitimate concern, although a casual analysis of the previous elections shows a higher propensity for the elites to use violence when the incumbent is fighting for re-election than when not. Since the incumbent, Uhuru Kenyatta, is not fighting for re-election, we should, at least, be optimistic that the 2022 elections will not result in large-scale violence.

In this article, we go further and suggest that not only will the August 2022 elections be relatively peaceful (relative to the 2007 elections) but also that Kenya’s history of large-scale political violence, may be a thing of the past. We base our prediction on the shift in the institutional and political landscape, facilitated by the political settlement that emerged out of the 2007/2008 post-election violence (PEV).

The key imperatives include the intervention by the International Criminal Court (ICC), the demobilisation of the highly charged political competition through devolution and the implicit peace commitment and political contract between Kenya’s political elites and the citizens that has considerably diffused political tensions and the febrile atmosphere that previously nurtured large-scale violence. We argue that the three factors have, to an extent, fostered a tacit agreement among Kenyans that large-scale violence is too high a price to pay for any short-term political gains.

As in other sub-Saharan African countries, Kenya’s transition to “democracy” has had confusing implications—facilitating multi-party competition and regime change through the ballot, but also fomenting political instability through violent politics. Although the root cause of political violence in Kenya has been primarily linked to the “land question” and the instrumentalization of grievances around land and resettlement, other accounts have focused on the elite fragmentation and state informalisation that began under Daniel Moi and continued under Mwai Kibaki with the inevitable diffusion of violence from the state to local gangs.

With the first two multi-party elections—in 1992 and 1997—being violent, many observers had come to expect political violence to be a natural outcome of Kenya’s elections until this conjecture was disrupted by the scale and intensity of the 2007/2008 PEV. With Kenya tottering towards anarchy, and fearing complete state collapse, the international community was forced to intervene in 2008, to not only halt the bloodletting but also engineer a major institutional reset through the 2010 constitutional change, and chaperone retributive justice via the ICC mechanism.

With Kenya approaching another election, and ten and five years respectively after the constitutional changes and the collapse of the ICC cases, we take stock of the implications of these major events on Kenya’s political landscape.

The ICC’s intervention in Kenya

First, the ICC’s intervention in Kenya was remarkable as it was the first time that attempts were made to hold the country’s political elites accountable under an institutional mechanism that they could neither intimidate nor corruptly influence.

While observers have either lamented or celebrated (depending on one’s ideological leaning) the failure of the ICC to successfully prosecute the so-called “Ocampo Six” (those the Court interdicted for their alleged planning of the 2007/2008 PEV), we argue that evaluating the performance of the ICC in the Kenyan crisis should be against its unprecedented attempt to confront the intractable impunity among the country’s political elites.

Since its post-independence birthing, Kenyan politicians had perfected the art of self-preservation through the construction of the perception that they were untouchable and above the law. The ICC, by hauling to its dock some of the big names in Kenya’s political landscape, including the current president, Uhuru Kenyatta, and his deputy William Ruto, and in so far as it has fractured the elites’ pejorative attitude towards the rule of law, the court’s intervention should be viewed as a partial success. Consider the narration of utter shame, frustration, humiliation and stigma among the “Ocampo Six” following their interdiction by the ICC, which clearly manifested their shock at being made to account under a neutral institution.

It was, therefore, not surprising that the accused and their enablers engaged in Machiavellian tactics, including counter-shaming strategies performed through neo-colonialism narratives, in order to delegitimise and undermine the ICC’s prosecutorial authority in Kenya and elsewhere in Africa. Whereas these strategies contributed to the inevitable collapse of the “Ocampo Six” cases, if the Court action has been successful in institutionalising fear of future intervention in Kenya as a credible threat against political mischievousness among the elites, and if it has blunted their assumed political invincibility, then the intervention should be viewed as partially successful.

The ICC’s intervention in Kenya was remarkable as it was the first time that attempts were made to hold the country’s political elites accountable.

Anecdotal evidence shows that the ICC intervention has brought Kenya’s politics to an inflection point by gravitating the country’s political discourse towards greater forbearance. This is clearly manifested by the assimilation of the “ICC” vocabulary into Kenyan public discourse, frequently invoked by ordinary Kenyans and politicians—including those who joined Uhuruto (as Kenyatta and Ruto have been popularly known) in the public vituperation of the Court—to credibly threaten those perceived to be engaging in inflammatory narratives.

Also, an empirical outcome from the ICC’s intervention has been the realisation among the Kenyan elites that accountability for inciting violence is no longer with the imagined political community of the “tribe” but, rather, on the individual politician. Consider the remarkable disposition by the elites to apologise and withdraw any inflammatory remarks attributed to themselves or to their lieutenants, something that was previously unthinkable.

A contributing factor to this “transparency” and the “politics of extenuation” has been the integration of social media in the way politics is chronicled and experienced in Kenya. The ubiquity of the smartphone, has ensured that the previous private sphere of reckless political talk and public deniability has been dissolved, as the private has become public via social media, forcing public apologies. Anybody, anywhere can now easily capture and post on social media negative political rhetoric that may yet, in the future, be used as evidence in court.

It is, therefore, not coincidental that the theatre of political violence in Kenya has recently shifted from the rural to the urban areas—with the state mostly implicated— thus blunting its association with specific ethnic groups and leaders. The ICC’s intervention in Kenya has to some extent fostered restraint against the large-scale political opportunism that was previously a feature in Kenya’s politics and responsible for the violence, ushering in a period of negative peace but with the potential of transitioning to positive peace in the future, if these imperatives can be harnessed and institutionalised.

Constitutional reset and institutional dividends

Secondly, the 2010 institutional reset through constitutional changes has yielded significant political dividends for Kenyan political elites in the form of devolution of power and resources to counties and provided access to resources through the political party funds allocated by the exchequer.

While these outcomes have not completely eliminated the fierce electoral competition synonymous with Kenya’s elections, we think that it has to an extent toned down the competition as losers now have alternative access to power and a platform from which to articulate and implement their policies. This has recently been manifested in the political tussling over local electoral seats—in the form of zoning—as the two major coalitions, Azimio and Kenya Kwanza, attempt to craft a strategy that will ensure their dominance in the local seats in the August polls.

Previous analysis has shown that the institutional context under which elections are organised can either moderate or escalate adverse outcomes, including violence. Institutional designs that afford greater opportunities for losers through certain “sweet points”, including fair treatment of losers, may reduce tensions and appetite for political violence.

For Kenya, while the desired “sweet points” has not been fully achieved because decentralisation has widened patronage networks, it may yet provide vast “eating” opportunities for losers of presidential elections and their followers even as they wait to compete in the next polls. Likewise, losers in presidential elections may also be co-opted into the decentralised graft network through elected proxies, as some anecdotal evidence shows.

The ICC’s intervention in Kenya has to some extent fostered restraint against the large-scale political opportunism that was previously responsible for the violence.

Meanwhile, the provision of political parties’ funds by the exchequer on the basis of the parties’ performance in local elections has also created opportunities for parties that compete in elections to access alternative resources. While there is yet no evidence of the extent to which this may have impacted political competition in Kenya, we think that it has shifted the former singular attention given to national political competition to local elections. This is because political leaders have had to strategize in order to win significant seats in local elections in order to access the funds. Consider the revelation that the ODM party is owed KSh 7.5 billion by the Office of the Registrar of Political Parties (ORPP) and the protracted infighting among the former NASA coalition partners over these funds.

On a different note, the creation of various political positions by the 2010 constitution, be they governor, senate or running mate positions, has rendered coalition building in Kenya a delicate affair as major political leaders have been forced to expend their political energy, previously fundamental to the orchestration of violence, on party politics at the expense of national political organisation. The creation of these positions and the dawn of ex-ante coalition building in Kenya has unexpectedly rewired political scheming from the national to internal, as manifested by the ongoing contestation over various seats in the forthcoming elections.

Cumulatively, we think that these institutional “dividends” —including devolution, the provision of political party funds and the creation of diverse political positions—have generated diverse opportunities to be competed over by Kenyan politicians and this may yet deter the need for large-scale mobilisation of groups for political violence.

Violence fatigue

Thirdly, findings from recent fieldwork in Burnt Forest by one of us show that there is acute fatigue among Kenyans from the recursive violence and this is fostering some degree of tolerance for, and openness to, hitherto political nemeses. The fatigue has been especially reinforced by the realisation among Kenyans that the elites’ concerns are for their own interests and self-preservation.

Consider the dissatisfaction and grumbling that accompanied the political rapprochement between Uhuru Kenyatta and his long-term rival Raila Odinga in 2018. The reconciliation, popularly known as the “handshake”, wrong-footed the support base of both leaders, who were of the opinion that the political settlement was motivated more by Kenyatta and Odinga’s narrow interest of perpetuating conditions favourable to the durability of the dynastic political order, and less by genuine national interest.

Because the rapprochement did not yield retributive justice and compensation for the victims of political violence, it gave way to despondency among ordinary Kenyans. Most have since opted for suboptimal political outcomes, especially stability, whatever the electoral outcome, aptly conceptualised by the phrase “accept and move on” to capture the inherent need to sidestep the negative externalities associated with Kenyan elections.

Recent evidence from Burnt Forest shows that violence fatigue may have fostered tolerance among local groups and made them less supportive of large-scale collective violent action, precisely because previous violence yielded asymmetric outcomes—economic and personal losses for the citizens and political gains for the political class. However, the full extent to which violence fatigue and citizen despondency may result in wholesome political stability in Kenya is something that needs further investigation.

Because the rapprochement did not yield some form of retributive justice and compensation for the victims of political violence, it gave way to despondency among ordinary Kenyans.

In conclusion, while it may be too soon to form concrete opinions on the feasibility of large-scale political violence occurring in Kenya in the upcoming elections and in the future, we have argued in this article that the ecology of events including the ICC’s intervention, institutional dividends and violence fatigue among ordinary Kenyans may yet immunize the country against large-scale political violence.

We are aware that peace spoilers may emerge and threaten violence as a way of gaining power or accessing political office through some form of political settlement, but for now it seems that Kenya is at the point of a halfway house, occupying the institutional space between negative peace and the possibility of positive peace in the long-term, if these factors are institutionalised.

As long as the threat of the ICC endures, devolution and the political party funds are maintained and the Faustian bargain between Kenyan citizens and the political elites remains stable—that is, selecting peace whatever the political outcomes—it is just possible that large-scale political violence akin to that witnessed in 2007/2008 may never again happen in Kenya.

But again, as Putin’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has shown, “Never Again” moments have the tendency to yield the very same conditions that were responsible for eliciting the “Never Again” statement. We, therefore, must remain hopeful but realistic that a major peace spoiler may yet emerge and usher in political disorder in Kenya.