On a cold Friday afternoon in July, Wambui is standing in the doorway of her roadside shop scrolling on her tablet. The street outside is empty. A woman wrapped in a Maasai shawl sits in a white plastic chair inside the shop. In front of her are plastic toys, vacuum cleaners, and electronic cutting equipment. A CCTV camera is mounted in the ceiling.

The shop is on a busy street in Ngara, Nairobi, and as I approach, Wambui calls to me to have a look at her wares.

“UK fridges are of high quality,” says the shopkeeper. A small refrigerator with no brand name is going for KSh20,000. “But I’ll sell it to you for KSh18,000. It is the best I can do,” she says.

Wambui has been in the business of selling imported second-hand appliances for about a decade. She says it is impossible to recall the number of cooling appliances she has sold, all imported from the UK through a middleman.

Inside the freezer compartment of one of the fridges are phone numbers in blue; 0870 is a premium help number for Domestic and General, a repair company in the United Kingdom, 0121 is a Birmingham number for spares. Birmingham is the United Kingdom’s second largest city.

Large imports

Despite being a signatory to international treaties regulating and banning the dumping of damaged and end-of-life electronics, Kenya still imports large quantities of electronic and electrical goods that are considered too inefficient to be sold in the country of origin. The appliances enter the country legally and a tax is paid to customs for their clearance.

Nairobi, Mombasa and Eldoret have thriving second-hand markets for cooling appliances, numerous repair shops and dealers in scrap. I visited some 20 shops, the majority of which were selling appliances from the United Kingdom while others were trading in appliances from Germany, United States, India, and even Sweden in one case.

Nearly all the shops have an online presence, either on Facebook, on Instagram, Pigiame.co.ke, and Jiji.co.ke, while some use WhatsApp groups to post photos of appliances and their prices.

But this trade in obsolete and inefficient second-hand cooling appliances that are harmful to the climate is not regulated. In effect, Kenya lacks a proper e-waste law and does not have the capacity to manage hazardous substances from cooling appliances that have reached the end of their life. An Electronic Waste Bill was formulated in 2013 but was never passed into law.

“Heavy metals like mercury, zinc, cadmium are harmful when they come into contact with the human body or natural resources like water,” says Boniface Mbithi, the Chief Executive Officer of WEEE Centre, an e-waste recycling company. “When plants absorb water that is already contaminated with heavy metals, and people eat these plants, [this] causes cancer, kidney failure, or even leads to mental disorders.”

This trade in obsolete and inefficient second-hand cooling appliances that are harmful to the climate is not regulated.

Tony, a fridge repairman, sells fridge compressors and freezers from Germany and the United Kingdom. He cannot afford direct shipments like Wambui but he has his way of getting around that obstacle; sourcing his goods from towns like Mandera and Garissa that border Ethiopia is his best alternative. He is unaware that old, inefficient refrigerators can leak harmful gases into the atmosphere during repair.

“I have to check if they are working before they are released into the market. Some come broken. I repair them, refill the gas, and change the compressor,” Tony said. But despite his best efforts, not all appliances are reparable. Those, Tony says, are sold as scrap in the informal recycling sector.

Unaware of the harm refrigerants can cause, scrap dealers release the gases into the atmosphere as they try to recover valuable components from the appliances, contributing to the depletion of the ozone layer and to climate change.

Improper disposal

Brian Waswala Olewe, an environmental education specialist at Maasai Mara University, notes, “Improper disposal of the refrigerant into the environment destroys air quality and affects health. . . . Freon, an odourless gas, cuts off oxygen supply to organs and cells and leads to cardiac arrest and death when deeply inhaled.”

Yet, Kenya does not have accurate data on imports of cooling appliances, especially refrigerators and air conditioners. The Customs Department of the Kenya Revenue Authority claims that it does not have specific records of the second-hand cooling appliances entering the country because most imports of these electronics come in consignments together with other goods.

Although Kenya is a signatory to the Montreal Protocol – an international treaty to protect the ozone layer by phasing out the production of numerous substances that are responsible for ozone depletion, such as hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) which may be contained in cooling appliances – these refrigerants are still finding their way into the country.

A common trend in the Kenyan second-hand market is the sale of electronics without appliance specifications, making it impossible for consumers to determine the quality of the products they are buying. Without these details, it was impossible to identify the refrigerants present (the compounds that provide refrigeration in air conditioners and fridges) in the appliances sold at Hoist Refrigeration Services, a major dealership in Utawala, along the Eastern Bypass in Nairobi.

However, investigations show that the presence of R134a, a hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) refrigerant is rife. Although R134a does not pose a threat to the ozone layer because it does not contain chlorine, it is still a potent greenhouse gas with a very high potential to cause global warming and its production is being phased out under Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

“We call it an Ex-UK fridge,” explains a saleswoman who is clearly ignorant of the chemical makeup of the electronics on display at Hoist Refrigeration Services. “I have sold so many ex-UK fridges and have never had a complaint about the energy consumption,” the seller said. But contrary to the seller’s claims, a UNEP report on energy efficiency standards states that Kenyans spend an additional US$50 to US$100 on electricity every year because of using obsolete and inefficient second-hand equipment and appliances.

Banned substances

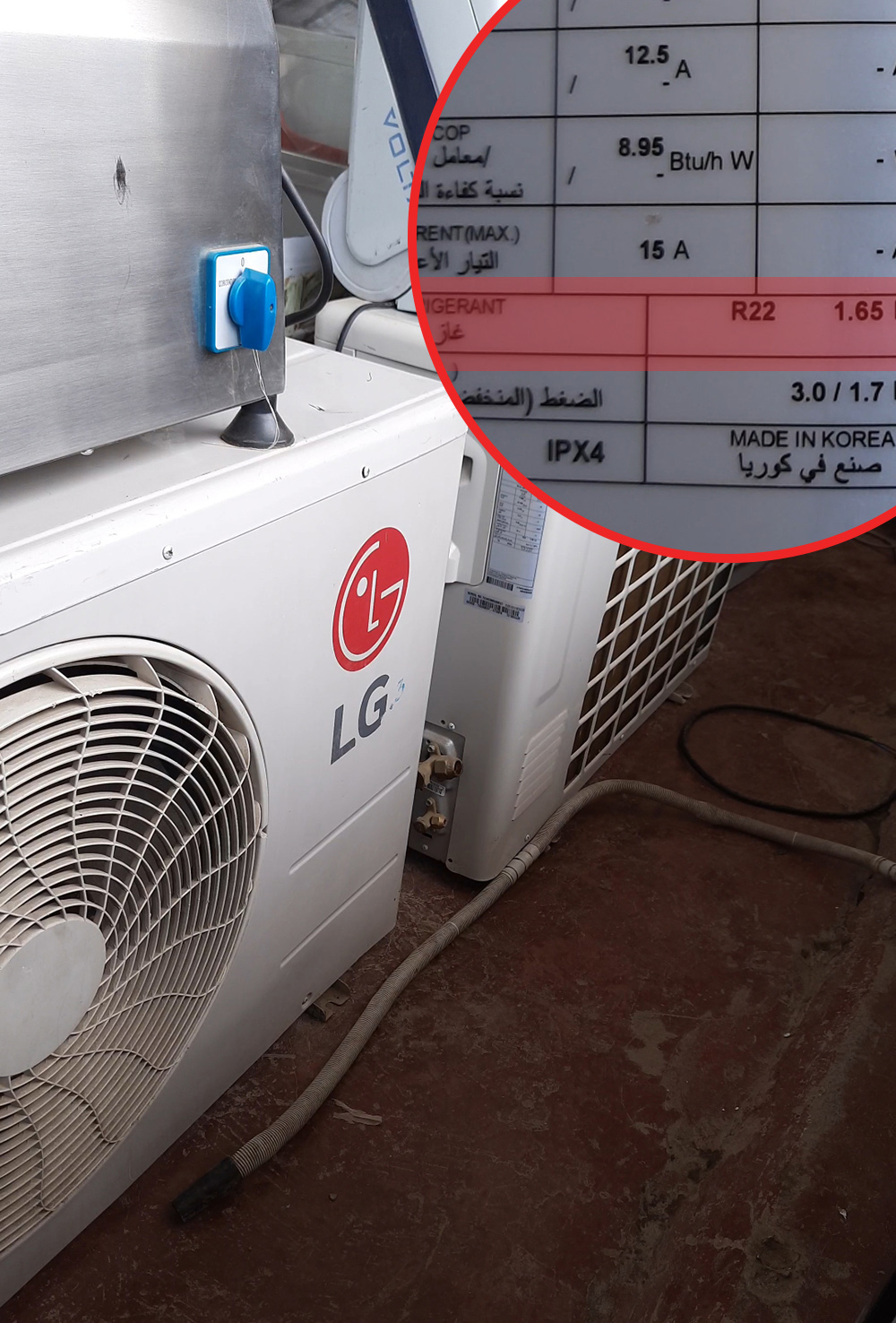

An environmental dumping report released in 2020 by the environmental campaign group CLASP and the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development revealed that the air conditioners sold in Kenya contain banned and environmentally harmful substances, with 37 per cent not meeting energy efficiency ratings above 3.0 W/W, a common standard around the world.

According to the report, Kenya imported between 30,000 to 40,000 air conditioners, of which 27 per cent contained R-22 (Freon), a refrigerant that contributes to the depletion of the ozone layer and is being phased out; 4 per cent contained R-32, a refrigerant that contributes highly to global warming; and 69 per cent contained R410a. (One kilogram of this refrigerant has the same greenhouse impact as two tonnes of carbon dioxide.)

The obsolete and harmful refrigerants and appliances were imported from China, Malaysia, Thailand and India.

Tad Ferris, Senior Counsel for the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development and lead author of the joint report, said the units are “energy vampires”, sucking up vital energy needed to recover from the pandemic and the economic slowdown, and inflating consumer spending on electricity bills.

Kenyans spend an additional US$50 to US$100 on electricity every year because of using obsolete and inefficient second-hand equipment and appliances.

However, the Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority (EPRA) has denied the existence of electronics without labels in the market. In an email response EPRA, which is responsible for monitoring and labelling of quality standards and energy performance of electronic equipment in Kenya, said, “The Authority does compliance inspections on a monthly basis across the country and has not seen any household refrigeration appliances and split-type non-ducted air conditioners lacking labels.” The email further said, “not all cooling appliances are governed by the standards and labelling scheme.”

In Kenya, the energy efficiency label is a red and green tag that awards a maximum of five stars on electronics and electrical appliances such as air conditioners and refrigerators. Minimum Energy Performance Standards are outlined in KS 2464: 2020 by the Kenya Bureau of Standards (KEBS), the country’s quality and standards body. To enter the market, appliances must be inspected and cleared by KEBS and other enforcing agencies, including the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) and Customs.

The Energy (Appliances’ Energy Performance and Labelling) Regulations were introduced in 2016 and promoted by CLASP and the Kenyan government under the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (KCEP). However, although Kenya has pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 32 per cent by 2030 to comply with the Paris Agreement under the revised National Determined Contributions (NDCs), it has yet to ratify the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal protocol that restricts the production, entry and use of HFCs such as R134a.

Not only do second-hand cooling appliances consume more energy and rely mostly on fossil-based energy to power them, they contain refrigerants that have the capacity to warm the atmosphere thousands of times more than carbon dioxide. A Study shows that the cooling appliances industry contributes significantly to climate change and accounts for 10 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

According to Dr Collins Odote, an environmental lawyer and Associate Dean at the Faculty of Law of Nairobi University, for Kenya to reduce greenhouse emissions and combat climate change, the country must eliminate the importation and use of banned substances, reduce reliance on fossil fuels and use clean energy. Kenya is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change. The country’s economy depends largely on tourism, agriculture, forestry and fishing, all sectors that are susceptible to climate change, Odote says, adding that the increased temperatures contribute to the loss of billions of shillings through droughts, famine, floods and human displacement.

Bribery and corruption

In order to get a sense of how these operations run under the radar of the authorities, I presented myself to some of the dealers as a prospective player in the business. It turns out that for bulk imports, which are cheaper, a contact — often a relative — in the exporting country is required.

Moreover, money to bribe your way out of the port is a necessity some said, and there were allegations that not bribing certain officials could result in clearance delays or impounded goods.

One of the dealers was open to doing business with me against payment of KSh10,000 for a connection to a middleman based in the UK. The deal didn’t go through, however, as a few days later, the middleman declined.

The obsolete and harmful refrigerants and appliances were imported from China, Malaysia, Thailand and India.

Experts say that rich countries are dumping e-waste in developing countries such as Kenya under the guise of exporting second-hand appliances. Exporting e-waste, non-functioning or near-end-of-life, or environmentally harmful refrigerants is a criminal act under the Basel Convention and the European Union Waste Shipment Regulation.

Yet according to a United Nations University study of transboundary movements of used and waste electronic and electrical equipment (UEEE), between 2008 and 2013, 184 tonnes of used freezers and fridges worth €1.5 million were exported to Eastern African countries, including Kenya.The study analysed EU exports of second-hand refrigerators, freezers, laptops and desktop computers considered as waste using trade statistics from the EU COMEXT database. The analysis revealed that most exports came from Germany and Great Britain. The study did not capture data on electronics exported unconventionally and therefore the number of cooling appliances could be higher.

This indiscriminate dumping of e-waste from developed countries is exacerbating the problem of e-waste management in Kenya where just one per cent of the 51.3 tonnes of e-waste generated domestically is properly managed and recycled while the rest is discarded carelessly in dumpsites and in rivers, incinerated, thrown into pit latrines or left in homes.

Speaking in an interview, Dr Ayub Macharia, Director of Environmental Education in the Ministry of Environment said, “Kenya is a victim of illegal movement of e-waste from developed countries.”

To curb dumping of e-waste in Kenya, Dr Macharia declared a ban on the importation of second-hand electronic devices starting January 2020. But the ban mainly affected old cell phones, computers and laptops sent by donors to schools and institutions and not obsolete cooling appliances.

Kenya’s biggest dumpsite

Dandora is Kenya’s fourth largest slum and home to the biggest dumpsite in Kenya. It is high noon but the sky here is grey from the swirls of smoke rising from burning waste.

Kevin, a scrap dealer, sits in front of a shack constructed from rusty corrugated iron sheets held together with cable and wire mesh. The middle-aged man agrees to divulge the secrets of his business anonymously.

“A client who imports sells me the broken ones. I get ex-UK, Japan and German-made appliances,” Kevin says. “I remove the copper and sell to jewellers or I take the copper to industrial Area, Mlolongo or Cabanas, to be exported to China.”

Kenya does not mine copper but the copper collected at scrapyards like this one is exported to countries like China and the UK, generating significant revenues for the country.

Kevin says he is just a tiny fish in the pond that is Kenya’s copper export market; politically connected people run the big deals. Security operatives visit his shop on a daily basis to collect bribes; he has secretly stashed away a large amount of copper in a storeroom somewhere to avoid exploitation from corrupt “CID” officers.

“Utachukua dawa? (Will you buy copper?) ,” an e-waste scavenger asks Kevin.

The copper trade is flourishing despite the harm caused to the environment and people by the release of refrigerants into the air. Kevin doesn’t have a degassing machine; he doesn’t see the need for one. He leaks refrigerants directly into the atmosphere as he recovers valuables like copper or steel.

One of the dealers was open to doing business with me against payment of KSh10,000 for a connection to a middleman based in the UK.

“There is no harm. The gases don’t have odour,” an ignorant Kevin says, adding, “That is a scientific theory. Even if it had, you cannot compare such pollution with one caused by a motorcycle.”

Kenya does not mine copper, so Kevin cannot get a licence to trade in the mineral. But the illegal trading, the harassment from corrupt government officials and the information that refrigerants cause harm to people and to the climate have not deterred him. Kevin says he’s already teaching his son the business.

“Utachukua dawa?” (Will you buy copper?), another waste scavenger asks Kevin.

This new business deal brings our chat to an end.

In another area of the dumpsite, James is sitting in his wood and corrugated iron shanty extracting copper from a fridge using a hammer. Around him are sacks containing various bits of scrap. To extract the copper from the appliances, the scavengers around Dandora use crude equipment, exposing other heavy metals and releasing gases into the air in the process. They complain of chest pains that they say are caused by the dark smoke emanating from the dumpsite.

James says he already has KSh200,000 worth of copper in a secret storeroom. The scrap copper is from fridges, construction sites and other sources. He hopes to collect KSh1,000,000 million worth of copper and maybe sell it by the end of the year. The copper will be exported to the United Kingdom, he says.

E-waste scavengers come carrying loads of copper that James weighs and pays for. He cannot tell where the copper brought to him has come from.

As I leave the dumpsite, rain falls from the heavy clouds above. In a few minutes, the water will flow in ditches and find its way into the Nairobi River a few miles away from the slum.

Hazardous substances

Scientific studies have confirmed the presence of dangerous elements, such as lead, which present a serious hazard to human health at the dumpsite. A study commissioned by UNEP found high levels of heavy metals in the surrounding environment and in the bodies of local residents.

Rich countries are dumping e-waste in developing countries such as Kenya under the guise of exporting second-hand appliances.

Lead and cadmium levels were 13,500 ppm (parts per million) and 1,058 ppm respectively, compared to action levels in the Netherlands of 150 ppm and 5ppm for these heavy metals. But because of the economic gains that they derive from the business, residents and collectors are not willing to abandon it or to move from the site.

To make matters worse, Kenya “[does] not have regulations that guide in e-waste management and disposal, we have them in draft,” says Dr Catherine Mbaisi, Acting Deputy Director, Environmental Education and Awareness, National Environment Management Authority (NEMA).

This means that influxes of obsolete cooling appliances through porous borders will continue to flood the market. According to Dr Mbaisi, the Ministry of Environment has formulated Extended Producer Responsibility Regulations that will render the manufacturer responsible for the entire life cycle of a product including a take-back scheme, recycling, and final disposal. She hopes the bill will be enacted.

Controlled Substances Regulations 2020 have also been formulated but have yet to be enacted. The regulations will promote the use of ozone-friendly substances and products, and ensure the elimination of those that deplete the ozone layer. They need to be urgently enacted because lack of regulation and the lax control of energy-hungry, toxic goods is putting Kenyan lives at risk and harming the environment.

–

This article was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project. Additional research by Leslie Olonyi