As Uhuru Kenyatta mounted a political comeback by campaigning against corruption, his family’s secret fortune was growing offshore, a massive new leak shows.

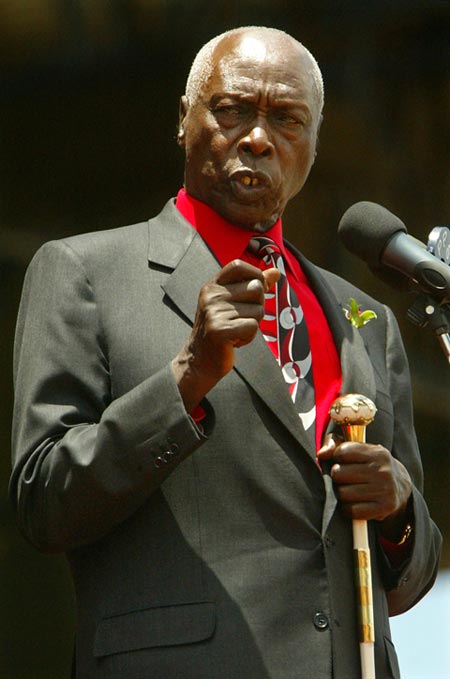

At his annual State of the Nation address last fall, President Uhuru Kenyatta mounted the podium at Kenya’s Parliament to acknowledge that too many Kenyans live in poverty and too many officials loot the country’s public resources.

The son of Kenya’s first president and leader of one of Africa’s largest economies, the 59-year-old Kenyatta urged lawmakers to join him in fighting corruption and yet again declared “the centrality of transparency, accountability and good governance as the anchors of sustainable development.”

But a massive cache of newly leaked documents show that Kenyatta’s family has for years been secretly accumulating a personal fortune behind offshore corporate veils.

Kenyatta, along with his mother, sisters and brother, have for decades shielded wealth from public scrutiny through foundations and companies in tax havens, including Panama, with assets worth more than $30 million, according to records obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with more than 600 reporters and media organizations around the world.

The records – from the Panamanian law firm Aleman, Cordero, Galindo & Lee (Alcogal) – show that the family owned at least seven such entities, two registered anonymously in Panama and five in the British Virgin Islands. One BVI company owned a home in central London, according to the records, and two other companies held investment portfolios worth tens of millions of dollars. The Kenyattas’ offshore wealth, revealed here for the first time, represents part of an estimated half-billion-dollar family fortune amassed in a country where the average annual salary is less than $8,000 a year.

The family began to accumulate much of its offshore wealth while Uhuru Kenyatta was a rising political star. Two offshore companies were created during an investigation into alleged looting of the public treasury during the watch of President Daniel arap Moi, Kenyatta’s former political patron.

Under Kenyan law, the president must provide a list of financial interests to the Ministry of Finance each year. Kenyatta and his family members did not respond to requests for comment, including whether he declared any offshore interests or was required to do so.

Details of the Kenyatta family’s offshore wealth have been brought to light by the Pandora Papers, a collection of more than 11.9 million records from 14 law firms and other service providers based in the United Arab Emirates, the Seychelles, Panama, Singapore and other tax havens.

The investigation has revealed assets of 35 current or former world leaders, including the king of Jordan, the prime minister of the Czech Republic, and Kenyatta’s fellow African leaders Ali Bongo Ondimba of Gabon and Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of Congo.

The discovery that Kenyatta and his family owned Panamanian foundations and a string of shell companies provides a jarring contrast to Kenyatta’s projected image as a transparency advocate. Documents show that the expansion of the Kenyattas’ offshore holdings coincided with Uhuru Kenyatta’s political rise, with increasing the layers of secrecy to shield the family’s wealth from scrutiny even as Uhuru solidified his role as a man of the people.

The ‘burning spear’

The story of the Kenyatta family fortune, with its various companies and foundations in tax havens, begins with an ambitious tribal scion who would become one of post-colonial Africa’s most iconic leaders: Jomo Kenyatta.

Uhuru Kenyatta’s father was born Kamau Ngengi circa 1894 in the fertile Central Highlands of what was then known as British East Africa. Kamau’s father was a village chief in the powerful Kikuyu tribe, in a country where tribal affiliation often determines the outcome of elections. Educated at a Christian mission school, the young Kamau signaled his ambitions by taking the name Jomo Kenyatta, a local word for “burning spear.”

At the start of the 20th century, a British colonial government tightened its grip on the region’s non-white population. A “hut tax” was imposed on people with little or no money, many of whom depended on their crops and livestock for survival. Some were driven to prostitution or consigned to forced labor.

Like many of his contemporaries, Jomo Kenyatta rebelled.

“Nothing is more important than a correct grasp of the question of land tenure,” Kenyatta wrote in 1938, while attending university in London. “For it is the key to the people’s life.”

Jomo Kenyatta returned home to lead a pro-independence party and was quickly imprisoned by the British on unfounded and politically motivated charges that he led the nationwide rebellion then underway. When he left prison nearly nine years later, Jomo took charge of independence negotiations, and, in 1963, Kenya gained independence, with Kenyatta as prime minister. In 1964, he became the country’s first president, and he presided over an economic boom that burnished the country’s reputation as a post-colonial model.

But instead of building democracy, Kenyatta turned the fledgling nation into a one-party state marked by arbitrary detention, torture and political assassination. Promised land reform became a land grab: Kenyans found that property had simply changed hands from European elites to Kenyatta cronies.

A United Nations-backed commission would later find that in two years, one-sixth of all properties previously held by Europeans, including “vast farms” and valuable coastal real estate, were “cheaply sold” to Kenyatta, his family and his allies. According to the final 2013 report of Kenya’s Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, beneficiaries included Kenyatta’s fourth and most influential wife, Ngina, their children, including Uhuru, and Moi, Kenya’s vice president at the time.

“Throughout the years of his administration, both land grabbing and irregular land allocations were perpetrated by and for the benefit of the president himself, members of his immediate family, his relatives and friends,” the report declared.

Following Jomo Kenyatta’s death in 1978, in his 80s (his date of birth is unknown), Moi took over as president, as a result of complex negotiations designed to head off tribal feuds.

After an attempted 1982 military coup, Moi plunged Kenya deeper into authoritarianism, and over more than two decades, he looted more than $2 billion, a government-commissioned investigation would find.

Protected by their ties to Moi and by Jomo Kenyatta’s aura as father of the nation, the Kenyattas thrived.

Uhuru’s mother, Ngina, popularly known as “Mama Ngina,” was given 264 acres over decades, according to a later government probe, which recommended that the landholdings be revoked.

With vast landholdings and backing from international investors, the family built a business empire, acquiring large stakes in well-known Kenyan enterprises, including a media conglomerate,a major bank and upscale hotels.

In 1993, the family founded Brookside Dairy, which expanded across East Africa and is now Kenya’s largest milk producer. One of Jomo and Ngina’s daughters, Kristina Wambui-Pratt, became a shareholder in a company that builds housing from polystyrene panels. Another, Anna Nyokabi Muthama Kenyatta, married a gem-mining magnate and managed the Kenyatta family’s beachfront hotel. A discreet and camera-shy son, Muhoho, now controls the family’s finances, according to local media reports.

But none of Jomo and Ngina Kenyatta’s children rose faster or farther than Uhuru.

Named after the Swahili word for freedom, Uhuru played rugby (and socialized with Moi’s eldest son, Gideon) at a Nairobi private school. He graduated from Amherst College, an elite U.S. liberal arts institution, in 1985 and returned home to launch an agricultural business and enter politics. He became the chairman of a local political party in 1997, and Moi named him to lead the country’s tourist board.

Uhuru burnished his everyman bona fides by dancing in public, while managing to indulge an equally public taste for expensive watches.

In 2001, Moi appointed Uhuru Kenyatta to a vacant seat in Parliament and, a month later, to the cabinet. Under increasing internal and international pressure to retire at the end of his second term, as required by the Kenyan constitution, Moi tapped Kenyatta to run as his successor in the 2002 election, betting on the Kenyatta name and tribal connections. But a coalition of reformist opposition parties crushed the Moi-Kenyatta alliance, relegating the 41-year-old Kenyatta and his party to the opposition .

The new president, Mwai Kibaki, ordered a probe of the Moi administration and the insiders who had helped spirit money out of East Africa. He appointed Kroll Inc. – the private investigation firm that had unearthed the financial secrets of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein and Haiti’s Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, among others – to lead the inquiry.

Kenyatta was on the front lines of those who rallied to Moi’s defense.”The government should stop digging into the past,” Kenyatta told a rally of Moi supporters in western Kenya’s verdant Rift Valley near Lake Victoria.

But within a year, a leaked version of the Kroll report spilled into the headlines with blockbuster allegations: Moi and his inner circle had embezzled as much as $2 billion – more than twice what Kenya was receiving in foreign aid in a year — and stashed hundreds of millions of dollars in bank accounts overseas. The report alleged that Moi and his associates “laundered” and “parked” perhaps $400 million in accounts at Geneva’s Union Bancaire Privée and elsewhere. Kenyatta was not named in the report.

According to the report, the looting peaked in late 2003 after the new government took power. “A marked flurry of activity has been reported among ex-President Moi’s family and their close associates to pre-empt any possibility of losing their wealth to the government,” Kroll reported.

Moi denied wrongdoing and officials quickly announced that he would face no charges in exchange for a smooth transition of power. But the Kroll investigation’s linking ill-gotten wealth to Switzerland and Panama devastated his political legacy, and it raised questions about who else may have benefited from the regime’s looting.

Client 13173

One of the largest private banks in Switzerland, Union Bancaire Privée advises some of the world’s wealthiest people on how to manage their money. Its eight-story glass headquarters overlooks Lake Geneva and the nearby Prada, Versace and Mont Blanc storefronts.

Like other private banks, Union Bancaire Privée often works with law firms in the British Virgin Islands, the Seychelles and other secrecy jurisdictions to create, register and maintain shell companies – which are without real operations and which list paid stand-ins as corporate officers on official paperwork – and similar entities that help clients conceal their ownership and wealth.

Some “offshore” clients are private citizens seeking to avoid taxes in the country where they live or acquire their wealth. Other clients are politicians and public officials, who are called “politically exposed persons” in the trade, because their wealth is deemed more likely to stem from bribery or other forms of corruption.

In July 2003, the same month that Kenyatta defended Moi in public, records show that a Union Bancaire Privée lawyer, Othmane Naïm, asked Panama offshore specialists to help register a new foundation, to be known as the Varies Foundation. The foundation, like a trust, was designed to manage and shelter wealth for its beneficiaries.

Draft bylaws, also from July 2003, name the foundation’s beneficiaries: Uhuru Kenyatta and his mother. Later, records show, Union Bancaire Privée helped manage a foundation for Uhuru’s brother, Muhoho.

Invoices from Alcogal in Panama to the bank show that the Swiss advisers referred to the Kenyattas with a code: “client 13173.”

As with trusts and foundations offered elsewhere, including Belize (also South Dakota and Nevada), Panama foundations can be designed to allow families to transfer wealth from one generation to another, tax free. Typically, an individual, or “founder,” transfers assets, such as a bank account or real estate, to the foundation, which becomes the assets’ legal owner.

Panamanian foundations are prized, like trusts, because those who create them, the true owners of the assets, are not required to register their names with the Panamanian government. That secret remains with their lawyers. Any breach of confidentiality laws carries a jail sentence of up to six months, the same sentence imposed in Panama for certain categories of child abuse.

According to a World Bank study, foundations are a common tool to mask dirty money. Ferdinand Marcos, autocratic president of the Philippines, is alleged to have stolen billions of dollars while he ruled the country from 1966 to 1986, funneling millions through a Panamanian foundation.

Alcogal said that it complies with requirements where it operates and “performs enhanced due diligence on a client who is determined to be a high-risk customer.” It told ICIJ’s media partner, Finance Uncovered, that it has not provided services to the Kenyattas’ foundations since 2014.The foundations were eligible for suspension under Panamanian law for failing to pay annual taxes, Algocal said.

Naim told ICIJ that he could not respond to specific questions, but said “we always complied with all applicable legislations and regulations.”

The Pandora Papers reveal the Kenyattas also secretly owned offshore shell companies.

Muhoho Kenyatta owned three registered in the BVI, according to records: One had a bank account that held an investment portfolio worth $31.6 million in 2016; another had unspecified investments at a bank in London.

From 1999 to 2004, Ngina Kenyatta and her two daughters held shares in a BVI company, Milrun International Ltd. The sisters used the company to buy a London apartment in the upscale Westminster neighborhood, according to records.

Similar apartments in the modern brick building now sell for more than $1 million. The apartment was rented until July by an English member of parliament, Emma Hardy, according to public records. Hardy’s attorney said that she signed an ordinary rental agreement and had never heard of the company involved.

Return to power

Following elections in 2007, a sharply divided Kenya was under another coalition government, and, with part of the family fortune secreted offshore, Uhuru Kenyatta mounted a comeback, assuming a new political persona. The populist had become an anti-corruption reformer.

In public, Kenyatta vigorously espoused transparency, and anti-corruption activists praised him for his fight against graft.

When he ran for president a second time, in 2013, he toured the country, repeating seven “key pledges,” including food, water and electricity for all. He also promised security on the nation’s restive border with Somalia and stringent anti-corruption measures, including new laws and agencies to probe and punish wrongdoers.

“It is time to get tough on those who seek to use their positions of power for their own personal gain,” a coalition of four political parties, including Kenyatta’s, declared in their coalition manifesto.

That year, at the age of 51 and after decades of grooming, Uhuru Kenyatta was elected president.

In his first State of the Nation address, Kenyatta promised honest government and offered to forgo 20% of his salary.

Meanwhile, Forbes magazine, in 2011, ranked Kenyatta as Kenya’s richest person and the 26th wealthiest in Africa, estimating the family fortune at about half a billion dollars. And Kenyatta, as president, fought to keep some things secret.

Two months after Uhuru Kenyatta won the 2013 election, the same commission that examined corruption as far back as his father’s presidency reported testimony that Jomo Kenyatta had acquired vast tracts of land through illegal means. The commission also found that the elder Kenyatta had “interfered in the investigation” of the assassination of a political rival.

A furious Uhuru Kenyatta demanded a retraction, albeit only about land deals that cast suspicion on the origins of the family’s empire. After a heated debate, in which several commissioners refused to comply with Kenyatta’s demand, the majority retracted references to the deals and issued a revised report.

“Protecting the wealth and economic power of the family today seemed more important to the Kenyatta family than the implication than their father was involved in the cover-up of a murder,” Ronald Slye, one of the dissenting commissioners, recalled in an interview with ICIJ.

As Kenyatta approaches his constitutional two-term limit next year, He increasingly has staked his legacy on transparency.

“What we own, what we have, is open to the public,” Kenyatta told the BBC in 2018, referring to his family’s wealth. “If there is an instance where somebody can say that what we have done has not been legitimate – say so.”

He continued: “Every public servant’s assets must be declared publicly so that people can question and ask, what is legitimate? If you can’t explain yourself, including myself, then I have a case to answer. If you want to continue serving, you must make it public. Period.”

–

This article was first published by ICIJ.

Contributors: John-Allan Namu (Africa Uncensored), Purity Mukami and Simon Bowers (Finance Uncovered)