In 2016, ActionAid and Tax Justice Network reported that Kenya loses an estimated KSh100 billion (Currently US$1 = KSh110) annually to tax incentives – reductions in corporate income tax, customs duties or VAT ostensibly provided to encourage investment – that often benefit foreign corporations. This amount represented 5.8 per cent of that year’s KSh1.7-trillion government budget.

That same year, former head of the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) Philip Kinisu reported that Kenya loses about KSh600 million to corruption each year. At the time, this translated to about a third of the entire national budget. Earlier this year, the president said that over KSh2 billion is stolen every day from government coffers. Granted, this sparked quite the reaction on social media, but nobody really knows how much Kenya actually loses to graft. One of the main reasons for this is the opaqueness of public procurement.

For the government to provide services to the citizens of Kenya, it is at times necessary to contract with private entities to deliver goods or services. Indeed, the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act (Procurement Act) of 2015 provides a framework for efficient procurement by public entities. Under this framework, it is crucial that such procurement is conducted or implemented in a transparent manner. This is especially crucial when dealing with foreign-registered companies. Some may remember the story of CMC Ravenna, the Italian company that filed for bankruptcy in its own country shortly after it had received a KSh15 billion down payment by the Kenyan government for the construction of Arror, Kimwarer and Itare dams. The total value of the three contracts was KSh150 billion.

In 2013, Washington, DC-based think tank Global Financial Integrity (GFI) estimated that the Kenyan government lost potential revenues of KSh97 billion for the year to trade misinvoicing of which KSh21 billion was attributed to uncollected corporate income tax. Meanwhile, Kenya’s budget has been steadily increasing from KSh2.2 trillion for the 2015/16 financial year to KSh3 trillion for the 2019/20 financial year. And of course, most of the tax burden falls on ordinary Kenyans and is supplemented by heavy borrowing, which citizens eventually have to pay for.

So, how is it that multinational corporations are able to siphon so much money out of the country? And why is it that our government keeps dealing with them? To answer this question, I looked into one well-known multinational company with a strong base of operations here in Kenya: G4S.

Public procurement transparency and the case of G4S

Why G4S, you ask? G4S, recently acquired by Allied Universal for £3.8 billion (Currently £1 = KSh150), is a giant global multinational corporation. The world’s largest security firm, it is active in over 90 countries across six continents. In 2019 it reported annual revenues of £7.8 billion, equivalent to 40 per cent of Kenya’s budget and about 60 per cent of the government’s projected tax revenues for the same year. This figure is expected to shoot up to £13.5 billion following the acquisition. In Africa, where it is the largest private employer, the firm reported revenues of £405 million in 2018, which is roughly equal to the Kenyan government’s entire allocation to the health sector that year. Their most lucrative operations on the continent were in South Africa and Kenya.

Half the company’s global subsidiaries are registered in tax havens — a red flag for tax avoidance — and its Kenyan subsidiary is almost wholly owned by a Dutch holding company. Despite this, G4S has been awarded several contracts by public entities in Kenya such as Kenya Power, the Ministry of Energy, and the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). All this, combined with the presence of two prominent politicians on G4S Kenya’s Board of Directors, makes it the perfect case study of why we need more transparency in public procurement.

Poor track record

The company has a poor track record in several of the countries in which it operates. In the United Kingdom where it has its headquarters, G4S was in 2011 contracted to run Birmingham Prison for a period of 15 years. However, halfway into the contract period, in 2018, the British government had to take back control of the prison following a rise in violence, substance abuse, and three self-inflicted deaths within an 18-month period. The company also came under fire in 2011 after a Kenyan asylum seeker died while in their custody, just a year after an Angolan deportee died after being held down by three G4S guards on a plane, with fellow passengers hearing him cry out: “I can’t breathe”.

In Jordan, all six United Nations agencies reportedly cancelled their contracts with the firm after human rights activists highlighted the firm’s complicity in “Israel’s grave violations of Palestinian rights and international law through its partnership with Israel’s police.” A 2019 assessment of G4S’s operations in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates led to Norway’s US$1.1 trillion wealth fund, the largest in the world, excluding the company from its investments because of “unacceptable risk that the company contributes to, or is responsible, for serious or systematic human rights violations”.

The company also came under fire in 2011 after a Kenyan asylum seeker died while in its custody.

In Africa, the company has been implicated in the use of violence, including electrocution and beatings, to subdue prisoners in South Africa’s Mangaung prison. Here in Kenya, G4S has been in the news for all the wrong reasons. Some readers may remember the string of robberies back in 2011 that earned them the moniker “Gone in 40 Seconds”. In 2019, part of the KSh72 million cash in transit stolen from G4S by police impersonators was found buried in one of the perpetrators’ father-in-law’s backyard. A former employee was awarded KSh35 million in damages after being fired for rejecting the sexual advances of her superior. The company’s workers have repeatedly gone on strike due to low pay and inhumane working conditions. G4S security personnel beat up and caused grievous harm to refugees picketing outside UNHCR offices in Nairobi, and there have been accusations of G4S security personnel demanding bribes from refugees in Daadab seeking entry into the main UNHCR compound.

Government contracts

Yet despite all the negative publicity, the Kenyan government keeps entrusting G4S with taxpayer money through contracts that are not published in accordance with public procurement and access to information laws. In many jurisdictions, the principles of public accountability demand transparency in government spending, with very few exceptions, for example, on matters of national security.

Private companies in Kenya are legally entitled to a measure of confidentiality and the Access to Information Act does not expressly impose proactive disclosure obligations on private bodies. However, according to the Commission for Administrative Justice (the Ombudsman), “the requirements [of the Act] can be extended to private bodies that receive public resources and benefits, provide public services or [are] in possession of important public information”.

No, the Act does not expressly impose proactive disclosure obligations on private bodies. However, the requirements can be extended to private bodies that receive public resources and benefits, provides public services or is in possession of important public information #Julisha

— Ombudsman Kenya (@KenyasOmbudsman) February 22, 2019

In any case, both Kenya’s Access to Information Act and a 2018 Executive Order from the President require all government agencies to “maintain and continuously update and publicise . . . complete information of all tenders awarded”.

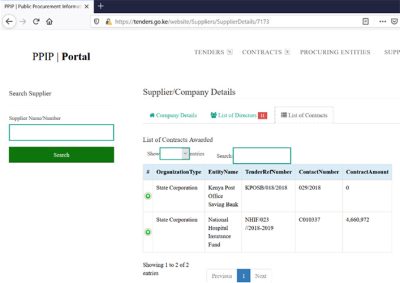

At the very least, one would expect government entities to publish their tender adverts and awards on the public procurement information portal (PPIP), which was created for exactly that purpose. However, when I went to search for contracts awarded to G4S, I only found two published contracts – one of very low value and one that did not even indicate the contract amount.

If the news articles and press releases on their website are anything to go by, G4S does a substantial amount of business with the government of Kenya, so a search on the PPIP should have yielded more results. This definitely heightened my curiosity even more, so I went a step further and conducted a good ‘ole google search: “Government contracts awarded to G4S” – I used different variations of the same search phrase, and while I found more results, none of them appeared on the PPIP.

For example, Kenya Power, the state corporation in charge of distributing electricity, has been consistently publishing each month’s tender awards on their website since March 2018. They published two awards to G4S in December 2019 and March 2020 worth KSh2,693,520 and KSh117,302,726 respectively. This is one example of a public entity that meets the legal threshold of publication under section 138 of the Procurement Act and section 131 of its attendant Regulations of 2020. However, it is unclear whether failure to publish on the portal would attract any penalty. The Ombudsman, which has been mandated with enforcing the Access to Information Act, did not respond to my query on this issue.

Additionally, G4S reported on its website that the Ministry of Energy awarded them the contract to secure the Lake Turkana Wind Farm Project (LTWFP), Africa’s largest wind power project. The details and value of the contract are undisclosed and unpublished. There are also several internet search results indicating various direct contract awards to G4S Kenya between 2015 and 2019, but the links are broken. None of these contracts has been published on either the Procurement Portal or the Ministry’s website, which is the minimum requirement for publication.

The two internet search results below also indicate that the Ministry of Energy may have awarded at least two contracts to G4S Kenya in 2017 and 2018. As with the above however, the links are inaccessible. They are also not on the PPIP or the Ministry’s website.

When I sent an email to the Ministry of Energy requesting copies of documents containing information on the total number of contracts awarded by the Ministry of Energy to G4S Kenya Ltd or any of its affiliates between 2014 and 2019, the Ministry’s response was, “Please note that we do not have such documents.” A follow-up request was ignored.

G4S also reported being awarded a 2-year contract worth KSh81 million to store, secure and deliver laptops to 8,600 primary schools under the digital literacy programme through which the president had promised to issue each standard one pupil with a laptop. Again, this tender award was not published by the public entities involved. However, I dug further and found that the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT) had published an article on their website indicating that they would be partnering with G4S and four other institutions to implement this project.

G4S’s role in this consortium was to distribute the devices to the schools. I wanted to understand how JKUAT, a public institution, arrived at the decision to contract G4S for this public project, and so I sent an information request to the corporate email indicated on their website. To their credit, I received an instant response from one Dr Ngonyo, directing me to the “directorate concerned who will be in a position to respond” to my enquiry. The email that I was given was not functional, and so I wrote him again, requesting an alternative email. Again, he replied instantly. This time, the email he shared did go through, but I have not received a response to date, not even an acknowledgement of receipt.

The digital literacy project ultimately fell short of expectations, with problems such as fewer devices being delivered than had been promised, lack of complementary infrastructure such as electricity, and inadequate ICT training of teachers. In the wake of COVID-19, the entire 2020 school year was cancelled, and public school pupils lacked the resources, or devices, to proceed with e-learning.

I also had the advantage of accessing a data leak from the Integrated Financial Management System (IFMIS), a financial management system that was rolled out by the government to enhance transparency and accountability in public procurement. The data showed that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) made payments of KSh5,548,930 to G4S between 2014 and 2017. These contracts have neither been published on the procurement portal nor in the IEBC’s reports. For instance, the IEBC’s annual report for the 2014/15 financial year included, on page 67, a list of all contracts fully executed between June 2014 and June 2015. There is no mention of contracts for the provision of security services, yet the IFMIS data shows that a total of KSh3,260,280 was paid to G4S between 28th October 2014 and 31st March 2015.

So what’s their secret?

As part of my research, I interviewed the operations manager of another established private security company operating in Kenya. Wishing to remain anonymous to protect the company’s business, my contact said that it is difficult to get government contracts, which are mostly awarded based on political connections. The manager indicated that many private security companies in Kenya are owned by ex-police officers and MPs, which gives them an advantage when bidding for government contracts.

I was unable to verify this information given that beneficial ownership disclosure was not legally required at the time of this investigation. This has recently changed, and companies had until 31st January 2021 to update their beneficial ownership information with the Registrar of Companies. However, by the time of this publication, it is not yet possible for citizens to submit beneficial ownership requests through the eCitizen platform. Companies have now been granted a grace period up to 31st July 2021 before the Registrar starts enforcing for non-compliance.

However, through the PPIP and the official companies search available on the eCitizen platform, I was able to determine that at least two politicians sit on G4S Kenya Limited’s board.

The first is Moody Awori, a 92-year old veteran politician who once served as Vice President under President Kibaki. He also served as MP for Funyala Constituency and as Minister of Home Affairs. He is credited with introducing prison reforms that improved conditions for inmates, but he was also implicated in the Anglo Leasing corruption scandal. According to his autobiography, Riding on a Tiger, Awori was appointed to the board of G4S, then Securicor Services, soon after it was registered in Kenya in 1963. In June 2021 he was still listed by the PPIP as one of the company’s directors.

According to former Permanent Secretary for Governance and Ethics John Githongo’s Anglo-Leasing report, the department of immigration was directly under Awori’s purview. He authorised a contract for printing of passports that was allegedly inflated to three times the cost. Even after a due diligence check by Mr Githongo and then Minister of Energy Hon. Kiraitu Murungi revealed that the contracted company did not exist, he authorised payments anyway. Awori still insisted he did no wrong and refused to resign from his position. At the time of this publication, the contents of the Anglo-Leasing report are the subject of a court dispute.

The second G4S Kenya director is John Matere Keriri, who was an active politician from the late 80s up until 2007. He was voted in as MP for Kirinyaga Central Constituency, formerly known as Kerugoya/Kutus Constituency in 1997, and was appointed as State House Comptroller by President Kibaki in 2002. Just before his dismissal from State House in 2004, he was approached by Dutch businessman Carlo van Wagenigen to assist with getting government approval for feasibility studies and government guarantees against financial risk for a business idea that would later become the Lake Turkana Wind Farm Project (LTWFP). According to Wagenigen’s account, his “good friend” Keriri set up a meeting with then Permanent Secretary for Energy Patrick Nyoike, who gave the green light for the project.

There is no mention of contracts for the provision of security services, yet the IFMIS data shows that a total of KSh3,260,280 was paid to G4S.

Upon his dismissal from State House in 2004, Keriri was appointed the Executive Chair of the Electricity Regulatory Board (ERB), which was succeeded by the Energy Regulatory Commission, and subsequently by the current Energy and Petroleum Regulatory Authority. The ERB was established to regulate the generation, transmission, and distribution of electric power in Kenya. This included setting, reviewing, and adjusting tariffs, as well as approving electric power purchase contracts between and among electric power producers and public electricity suppliers.

Incidentally, the power purchase agreement between LTWFP and the Kenyan government included a take-or-pay clause that saw taxpayers foot the bill for a KSh1 billion fine when the government delayed in building a transmission line to connect the wind farm to the national grid. The World Bank had earlier expressed concern over this clause that would burden consumers, and withdrew its support in 2012. According to Biashara Energy Solutions Ltd, a renewable energy SME where Keriri was a director, he was “one of the Chief Financial Advisors for Turkana Wind Power project who is attributed for structuring new financing model after the announcement of the World Bank to pull out of the project financing.”

Two years later, after almost a decade of feasibility studies and investment negotiations, project construction started and G4S announced that they had been awarded a contract by the Ministry of Energy to secure the wind farm on a three-year rolling basis for a period of 15 years. Available records show that Matere Keriri joined the board of G4S Kenya Ltd a year later, sitting from 2015 to 2017, though a search at the Company Registry conducted in May 2020 indicated that Keriri was still on the board. G4S has won tenders from the Ministry of Energy, under which the ERC falls, during Keriri’s tenure on its board. The details of these contracts, including the monetary value, are only visible as internet search results whose links are broken. They have not been published on the PPIP or the Ministry’s website as per the public procurement transparency requirements.

This should matter. The lack of information on contracts awarded to G4S and their monetary value obscures a high risk of conflicts of interest or, worse, may indicate that collusion, cronyism, kickbacks, or some other form of corruption was instrumental in G4S’s financial success. The Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Act tries to prevent this by prohibiting public officers from taking part in any procurement process in which they have an interest, and also expressly forbids inappropriate influence in procurement decisions.

Under section 176 of the Act, any person found guilty of violating this law faces up to 10 years of imprisonment or a fine of up to KSh4 million, or both. Should the offending party be a body corporate, then a fine of KSh10 million will apply. The Act also requires procuring entities to publish tender notices and awards. This means that any public entity that has failed to publish contracts awarded to G4S and other public entities is in breach of the law. However, the Act is unclear on whether this is a punishable offence.

Given the lack of publicly available information, Kenyan citizens have no way of checking whether they are getting the best value for their money with regard to these contracts.

G4S’s questionable corporate structure

According to records filed with the Company Registrar, G4S Kenya Ltd is 82 per cent owned by a Dutch holding company. In the world of financial crime and illicit financial flows, “Dutch holding company” is a red flag for tax avoidance. The snapshot below shows that the G4S structure comprises of a series of subsidiaries and holding companies ultimately owned by G4S plc based in the United Kingdom.

This should concern Kenyan taxpayers. This company structure raises questions of tax planning and tax avoidance, especially since Oxfam ranked the Netherlands third out of fifteen countries that “facilitate the most extreme forms of corporate tax avoidance”. The European Parliament has also labelled it a tax haven. Corporate tax havens have been known to help big business cheat countries out of billions of dollars every year and in fact, a 2016 study by Oxfam Kenya shows how companies in the extractives industry use conduit companies in the Netherlands for tax avoidance.

If public procurement continues to be shrouded in secrecy, then citizens will have no way of finding out whether G4S and other multinationals are indeed cheating the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) out of much-needed taxes, or whether they are relying on political patronage to win government contracts paid for by taxpayer money.

The need to strengthen the access to information regime in Kenya

When I reached out to G4S to clarify some of the points raised in this article, they told me that I had no written authority to write about G4S, and should I attempt to publish anything without their written authority, it would “cost me”. When private companies have dealings with the government, when they have prominent politicians sitting on their board of directors, and when they play critical public roles such as the provision of security, then citizens and especially journalists should have the right to look into their affairs, and the veil of secrecy ought to be lifted.

There is a need to demand increased accountability for companies that conduct business with government agencies. Without full disclosure, there is a potential risk that Kenya may be losing much needed tax revenues that would greatly ease the tax burden on ordinary Kenyans.

In the world of financial crime and illicit financial flows, “Dutch holding company” is a red flag for tax avoidance.

I also contacted the Commission on Administrative Justice, otherwise known as the Ombudsman, the agency in charge of enforcing the Access to Information Act of 2016. After my requests for information to JKUAT and the Ministry of Energy were denied, I asked the Ombudsman whether they could offer any redress mechanisms to citizens who are denied their right to information, or if government agencies faced any penalty for failure to disclose information. Ironically, I was informed that I had to write a formal letter on the letterhead of the organisation that I represented, which would then go through their internal processes before eventually landing on the relevant officer’s desk. As of the writing of this article, my request is still pending. Nonetheless, the Ombudsman indicated through their official twitter account that requests for information are valid as long as they provide sufficient details of the information sought. Furthermore, such requests do not have to be in writing.

Yes, requests should provide sufficient details of the information sought. This includes the particulars of the applicant, name of the institution from which the information is being sought, details of the information sought, and nature of intended access #Julisha

— Ombudsman Kenya (@KenyasOmbudsman) February 22, 2019

The request does not have to be in writing, it can be made orally. In such cases, the Information Access Officer should reduce it to a written form and give a copy to the person making the request #Julisha

— Ombudsman Kenya (@KenyasOmbudsman) February 22, 2019

Unless the government starts respecting the constitutional right of access to information, we shall continue to lose billions that could have gone towards the public good, such as for example, providing social services in education, healthcare, or social welfare cushions for small business owners that have been hit hard by the COVID-19 control measures.